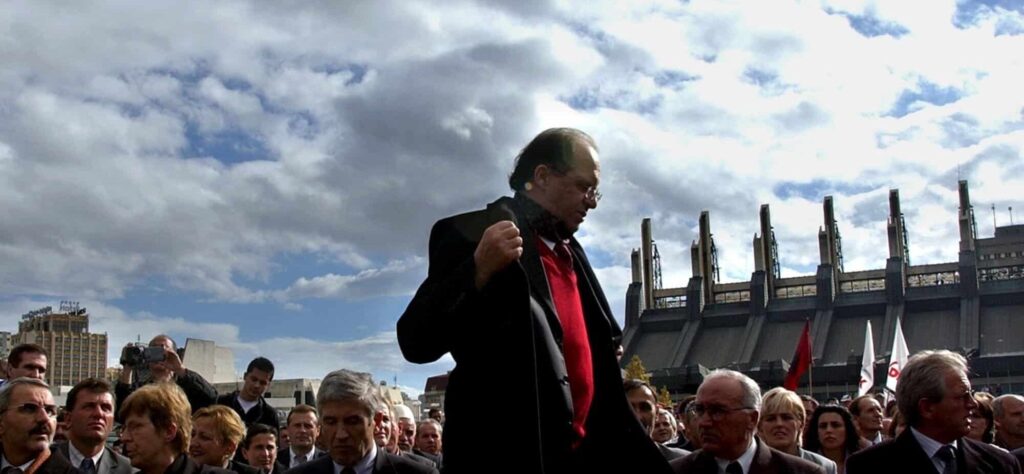

With his trademark silk scarf coiled around his scrawny neck, a thin column of blue smoke wafting its way from the ever-present cigarette in his nicotine-stained hand, Ibrahim Rugova was for years a deeply familiar, though enigmatic, figure to journalists and diplomats visiting Kosovo.

Frequently dismissed as yesterday’s man, above all when he shook hands and smiled at the Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic at the height of Serbia’s armed campaign in Kosovo, he consistently outsmarted his foes before cancer brought him down. Death overtook him just before the start of the internationally brokered talks that will seal the future of the territory whose independence he championed for so long.

In reality, he had already ceased to control day-to-day affairs in Kosovo, preferring to leave matters to the younger lieutenants of his Democratic League of Kosovo while he met and greeted foreign visitors, often presenting them with items from his treasured collection of mineral rocks.

Partly, this was because his real job was done. A quiet man who doggedly pursued the cause of non-violent struggle for independence from Belgrade, his often unpopular strategy had been finally vindicated when NATO did the job for him in 1999, forcing Serbia to evacuate the province it called Serbia’s “cradle” and so paving the way for its eventual self-determination.

The rise of Ibrahim Rugova to the status of “father of the nation” could hardly have been foreseen when he was born in the traumatic last months of the Second World War on 2 December 1944, near Istog, in western Kosovo.

The execution of his father, Uke, and grandfather, on 10 January 1945 by Yugoslav Partisan forces ensured the young Rugova would grow up deeply distrustful of the communist regime.

Educated in Peja/Pec and Pristina, a year spent studying literature at the Sorbonne from 1976-1977, proved formative. The experience of French intellectual life in the Latin Quarter of Paris left its mark on him.

Disdaining the military gear beloved by his Croatian counterpart, Franjo Tudjman, or the dreary business suits favoured by Milosevic, he would act the part of a Left Bank intellectual “manqué” for the rest of his days.

But the quiet life of the academic was not for him. In 1989, as new boss of Serbia, Milosevic dramatically scrapped the limited autonomy that Kosovo had enjoyed under President Josip Broz Tito, sparking fury on Kosovo’s streets. While youths hurled stones and petrol bombs impotently at the authorities, Rugova formed a new political party in December 1989 to challenge communist – and Serbian – domination. Named the Democratic

League of Kosovo, LDK, its title hearkened back to the 19th-century Prizren League, a movement that had first agitated for an Albanian state in the region under the Ottoman Empire.

While Milosevic consolidated power in Kosovo and Serbia, Rugova quietly built up the LDK as the pillar of a shadowy, alternative, Albanian structure, which ran its own social services and educational facilities independently of the Serbian authorities. Rugova was the moving spirit behind an underground ballot on Kosovo’s independence and the holding of parallel elections in May 1992, which the LDK duly won.

His non-violent strategy against the Serbs was tested in 1991 and 1992, as war raged in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina, and as many Albanians chafed to join the anti-Serbian armed struggle.

Rugova rejected the idea, convinced that an uprising would simply hand the Serbs the pretext he believed they sought to carry out a slaughter.

A bigger test followed in 1995, during the Bosnian peace talks at Dayton, Ohio, when it became clear that the international community would not exert any serious pressure on Serbia to make political concessions in Kosovo.

When a new, shadowy, militant force emerged over the following two years, named the Kosovo Liberation Army, KLA, Rugova appeared a spent force, even more so when he denounced the KLA as the work of Serbian “agents provocateurs”. He was still more compromised in May 1998, when, as the armed struggle between the KLA and the Serbs escalated, he was photographed shaking hands with Milosevic in Belgrade.

The failure of internationally-brokered peace talks over Kosovo at Rambouillet in February 1999 buried Rugova’s hope of a peaceful outcome to Kosovo’s agitation for self-rule and within weeks, NATO was at war with Milosevic, as his state-sponsored violence triggered a mass exodus of Kosovo’s Albanian population. Again Rugova was discredited when the Serbs released television footage of him talking to President Milosevic. Soon after, he escaped to Italy.

When the Serbs were forced to agree to a humiliating withdrawal from Kosovo that summer, power seemed likely to fall into the hands of the triumphant KLA and its charismatic young leader, Hashim Thaci.

But with the Serbs out of Kosovo, Albanian voters – much to the surprise of foreign commentators – declined to hand all authority to their self-appointed, khaki-clad liberators in the KLA. In elections in October 2000, they gave 58 per cent of their votes to Rugova’s LDK. Some 18 months later, in March 2002, Rugova was elected first president of a free, though not yet independent, Kosovo.

As head of the territory, he was frequently criticised as unfocused and lacking direction, and when ill health began to overtake him, it was apparent that his role in the forthcoming talks on Kosovo’s final status would only be nominal. Last September, his staff admitted he had cancer.

Nevertheless, his death still came as a great shock to Kosovo Albanians, for whom he represented stability and the longing for a more normal life, free from gunmen and paramilitaries.

With his studied indifference to flummery and presidential protocol, the air of an absent-minded professor still very much about him, he had become in the eyes of Kosovars a generally civilising influence – a symbol of their aspiration to be part of the European mainstream. To that extent, he fully warranted his “father of the nation” tag.

He was survived by his wife and three children.

This article was originally published on January 22, 2006. At the time of publication, Marcus Tanner was BIRN’s English-language editor – a position he still holds.

Postscript from 2025: Rugova’s standing grows posthumously

If a pedestrian walks for less than 15 minutes down Pristina’s main street, they’ll see three major tributes to the man who most Kosovo Albanians perceive as the ‘father of the nation’. A mid-size statue can be seen in front of the modern cathedral, for which Ibrahim Rugova set the founding stone in 2005, days before he would communicate to the public the news that he had cancer, which caused his death four months afterwards.

No more than 200 metres further on, there’s a giant poster of Rugova that was put up in February 2008, days before Kosovo declared independence – a move that Rugova strongly advocated but never got to experience for himself. And finally, just in front of the parliament building, there’s a huge statue of Rugova in the square named after him. The monument has become the protocollary venue for newcoming ambassadors to lay wreaths the day they present their credentials to the president’s office just across the square.

Rugova was widely admired for pursuing a policy of non-violent resistance to Serbian rule – at the time when the break-up of Yugoslavia was triggering bloody wars in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina in the early 1990s. Decades later, his policy is getting increasing retrospective recognition both at home and abroad. His grave in a neighbourhood above Pristina, not far from the residence where he lived and worked during the difficult 1990s, has become an important shrine for politicians and others to visit on the anniversaries of his birth and death.