During the second week of October, unprecedented full-fledged military confrontations broke out in northern Syria between factions of the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA), with Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) subsequently intervening in support of some factions over others. The escalation began when members of the al-Hamzah Division (HD) assassinated the political activist Muhammad Abu Ghanoum and his pregnant wife in al-Bab in eastern Aleppo on Oct. 7. In response, the Third Legion, which is dominated by the Levant Front (LF) and Jaysh al-Islam (JI), launched multiple attacks against HD and its ally, the Sultan Suleiman Shah Brigade (SSSB), driving them out of their military bases in Turkish-influenced rural eastern Aleppo and Afrin, known as the Euphrates Shield and Olive Branch areas, respectively.

On Oct. 11, HTS forces advanced into Afrin to support HD and SSSB against the Third Legion, which was joined by another SNA military coalition known as the Liberation and Construction Movement (LCM).1 At the same time, another front was opened between Ahrar al-Sham-Eastern Sector (ASES), which is close to HTS, and the Third Legion in northeast Aleppo. Three days later, HTS and its allies entered Afrin, expelled the Third Legion from its posts in the city, and marched toward Azaz in northern Aleppo, before a deal was finally reached between the warring parties that would supposedly put an end to the fighting.

Predictably, the deal collapsed and HTS advanced toward Azaz, prompting hundreds of locals to break into the Bab al-Salameh crossing with Turkey on Oct. 17. This pushed the latter to intervene and order the “Thaeroun Front for Liberation,”2 an SNA military umbrella group that maintained its neutrality during the infighting, to deploy as peacekeepers in Kafr Janah, temporarily ending the violence. A week later, the Turkish army intervened, stopped the fighting, and began to erect concrete barriers separating HTS areas in Idlib from SNA ones in Afrin.

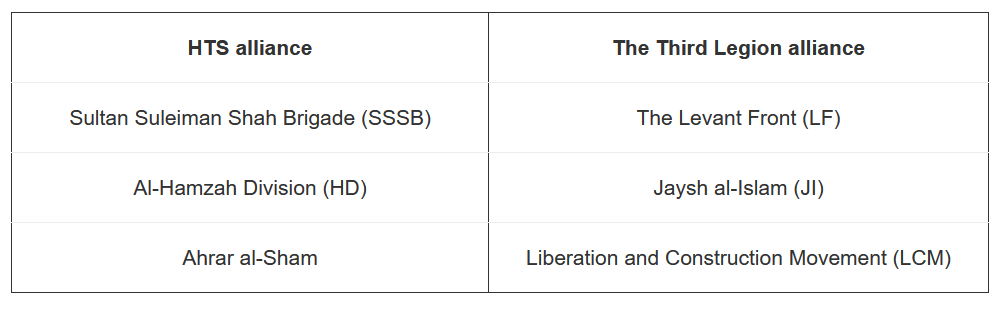

Understanding the SNA — its nature, organization, and the constantly shifting alliances between its factions — is a challenging task indeed. Formed in 2019 by Turkey, the group includes both local factions and those that were deported from areas in the Damascus countryside, Homs, and Daraa. Some of these factions are fully allied with Turkey, such as the SSSB, HD, Faylaq al-Sham, and the Sultan Murad Brigade, while others have trodden a thin line between their national agenda and Ankara’s interest to a lesser degree, like the LF, JI, and Ahrar al-Sham. Nevertheless, all of these factions are part of Turkey’s war against the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), but not all of them have participated in the Astana talks or sent their troops to fight in Ankara’s wars overseas. The below table shows the newly emerging alliances:

This article argues that Tukey’s weariness about the constantly deteriorating state of security in the north, resulting mainly from infighting among the SNA forces it backs, and its willingness to impose order on them, could explain its silence on HTS’s military aggression and advancement toward their area. For HTS, however, expanding its rule and settling scores with some SNA factions may be the main drivers behind its recent attacks.

Anarchy in the north

Turkey has an interest in stabilizing the north to stave off a potential influx of Syrian refugees into its territory and send back those already in Turkey. Yet this desire has often been hampered by the constantly deteriorating security situation resulting mainly, but not exclusively, from infighting between SNA factions. Ankara’s efforts to permanently resolve disputes and demarcate clear lines between these factions have rarely succeeded, allowing for new formations to emerge within the SNA and leaving space for bloody power struggles and competition over economic benefits between its leaders. According to a report published by the Carter Center in March 2022, there were at least 184 reported clashes among SNA fighters between March 2020 and Dec. 10, 2021, largely due to its leadership crisis, factionalism, tribalism, personal disputes, and the endemic corruption in its ranks. Turkey could and indeed has leveraged its financial support against the factions; such disciplinary measures, however, may have unintended consequences, pushing them to seek out or ramp up illegal activities to generate revenue, such as kidnapping, smuggling, and extortion.

Fueling this sense of anarchy is Turkey’s non-interventionist policy vis-à-vis the SNA factions. The Turkish army has never intervened to support one faction against another in previous rounds of infighting, and its involvement has often been limited to temporarily ending the violence and maintaining the status quo. Ankara did not intervene when HTS wiped out the Turkish-backed National Liberation Front from areas in northern Hama and southern Idlib and imposed its control over almost the entire city of Idlib in January 2019. Furthermore, when HTS advanced into the Turkish-controlled Olive Branch area in June to support the ASES against the Third Legion, briefly seizing multiple villages in Afrin’s southern and southwestern countryside, Turkey mediated a deal requiring the warring factions to return to their previous positions. Ankara’s reaction may thus have emboldened HTS to expand into the north.

The view from Ankara

Ankara’s belated and weak reaction to HTS’s recent advances speaks volumes; it allowed the group to march into the Olive Branch and Euphrates Shield areas, expel SNA soldiers, and force the withdraw of Faylaq al-Sham — Ankara’s favorite SNA faction — from areas separating HTS and SNA territories, enabling HTS troops to enter Afrin. Several factors can explain Turkey’s stance, chief among them is its weariness about the deteriorating state of security, which has hindered its efforts to deal with the refugee issue. Having a hegemon in the region that could forcibly but effectively provide stability and, to a lesser degree, governance while preventing a potential refugee influx may have been on the Turkish radar. By violently blocking the “Peace Caravan,” a campaign of 400 people marching toward the Bab al-Hawa crossing en route to Europe via Turkey in September, HTS demonstrated its willingness to prioritize Ankara’s interests. Furthermore, HTS’s brief advance into southern Afrin in June and its subsequent compliance with the Turkish withdrawal order, which was interpreted by some as a challenge to Turkish influence in northern Syria, sent a clear message to Ankara that it could be relied upon.

HTS rule over Turkish areas of control would likely provoke a local and international backlash. Nevertheless, in turning a blind eye to HTS’s bold intervention, Turkey may be “disciplining” the SNA factions that have dared to defy Ankara’s authority over the north. A source close to the SNA told the author that Ankara wants to “teach the LF a lesson for its disobedience.” Unlike Turkey’s yes men in the HD and SSSB, the LF refused to send its troops to fight in Libya and Azerbaijan on Turkey’s orders. Moreover, it closed the Bab al-Salameh crossing in northern Azaz in retaliation for Ankara’s decision to prevent LF officials from entering Turkey in April. By clipping the wings of “disobedient” factions, Turkey not only reminds them of its ability to undermine their rule but also empowers its ultra-loyalists, such as those now fighting alongside HTS.

HTS vs. SNA

HTS’s ambitions to expand its territory; gain access to commercial crossings with the SDF, the Syrian regime, and Turkey; and weaken the SNA are not new and reflect the group’s desire to consolidate its rule in northern Syria, increase its financial gains, and ensure its military hegemony over SNA factions.

The recent battles with the Third Legion provide HTS with an opportunity to deal a blow to its most potent rival, the LF, which dominates the Third Legion and is the cause of Ankara’s irritation. HTS’s leadership has long viewed the LF with suspicion due to its control over a significant swath of territory in rural western and eastern Aleppo, as well as its influence over other SNA factions, highlighted by its ability to bring about unity — albeit fragile — between several SNA factions under its command in the Third Legion or “Azm.”3 Additionally, the LF is considered the heir of the popular Aleppo-based Liwa’ al-Tawhid and enjoys notable local support due to its dominant Aleppine identity. This could be seen when hundreds of locals from different areas in rural eastern and northern Aleppo took to the streets on Oct. 16 to protest against HTS’s potential advance and in support of the LF. Another possible area of concern for HTS is the LF’s close relationship with the Turkey-based Syrian Islamic Council, which includes well-known and popular figures with religious credentials, such the Mufti of Syria in Exile Sheikh Osama al-Rifai, and may be seen as a challenge to the legitimacy of HTS’s Shura Council with its poorly educated members.

The bad blood between HTS and JI is another motive behind the former’s attacks against the Third Legion. Al-Ghouta-based JI waged a full-fledged war to uproot HTS from the area in 2017 when both groups were operating against the Syrian regime. Reportedly, around 500 fighters were killed on both sides during the infighting. One year later, JI coordinated with the U.N. to deport HTS fighters to northern Syria as part of the de-escalation zone agreement brokered by Russia, which was followed by the deportation of JI to other opposition areas in the north. HTS periodically accuses JI of handing al-Ghouta to the Syrian regime and threatens other SNA factions that cooperate with it, while JI regularly accuses HTS of destabilizing the region and causing dissension among the ranks of the opposition. A source close to HTS told the author, “HTS cannot trust JI and if it does not commit to the deal signed with the LF, it will be dismantled by HTS and other factions.”

Looking ahead

The Oct. 14 deal between HTS and the Third Legion stipulated an immediate end to violence, the release of all fighters arrested in recent events, and the return of Third Legion forces to their headquarters and positions (supposedly after being handed over by HTS). Pledges were also made that HTS would carry out no future attacks on the Third Legion and that there would be no prosecutions on either side. Also, both parties agreed to limit the activities of the Third Legion to the military field and to continue negotiations to better regulate and improve civil institutions. The deal did not mention HTS’s future role in opposition areas (particularly in Afrin), however, or the fate of the SSSB and HD, which fought alongside HTS against their “fellow” members of the SNA. While it is difficult to see the SNA trusting these factions again, the chances that they will join HTS also appear limited.

The vaguely worded deal did not put an end to the infighting, and it is unlikely to resolve the chaotic state of security in northern Syria. Indeed, clashes resumed in Kafr Janah, a town between Afrin and Azaz, on Oct. 17, amid continued HTS threats to enter Azaz, where the Third Legion has its base. The Turkish army’s belated intervention on Oct. 21 may help to quell the fighting temporarily, but it has little ability to address the long-standing grudges between armed factions.

It is unclear whether Turkey will allow HTS to expand it rule over the Olive Branch and Euphrates Shield areas in the future, especially after Washington has expressed concern. Nonetheless, a new reality is certainly taking shape. According to a source close to HTS, “HTS does not seek to have military control over the opposition areas. It rather wants to unite the region administratively under one entity in the hope of a future merger between its Salvation Government and the Turkey-based Interim Government.” HTS has already secured its influence in Afrin through its ally Ahrar al-Sham, which took control of HD military posts in Afrin that the LF had seized during the infighting, a development that was not mentioned in the deal. HTS also sent its Directorate of Humanitarian Affairs on a field tour of several villages and internally displaced person camps in the Afrin countryside on Oct. 14 as a reminder of the new reality.

The remaining challenge for Turkey, however, is how to instill lasting stability in a region full of unaddressed grievances among the different SNA factions. While HTS could provide security and governance in these areas in the long term, its local legitimacy will remain questionable. So too will Ankara’s ability to sell the new reality, in which a terrorist-designated group will rule over areas under its influence, to its allies in the West.