The Islamic State in the Great Sahara has sought to prioritize extending its scope, rather than sustainable entrenchment in its areas of action. This partly explains its rapid rise along the borders of Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso.

The rapid increase in violent activities of militant Islamist groups in the Sahel since 2016 has been mainly the work of three groups:

- The katiba Macina, centred around the region of Mopti and Ségou, in central Mali;

- Ansarul Islam, centred around the municipality of Djibo, in northern Burkina Faso;

- The Islamic State in the Great Sahara (EIGS).

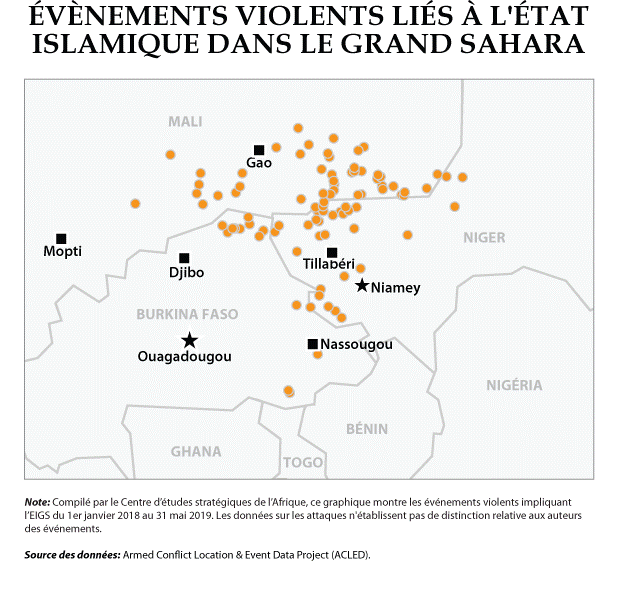

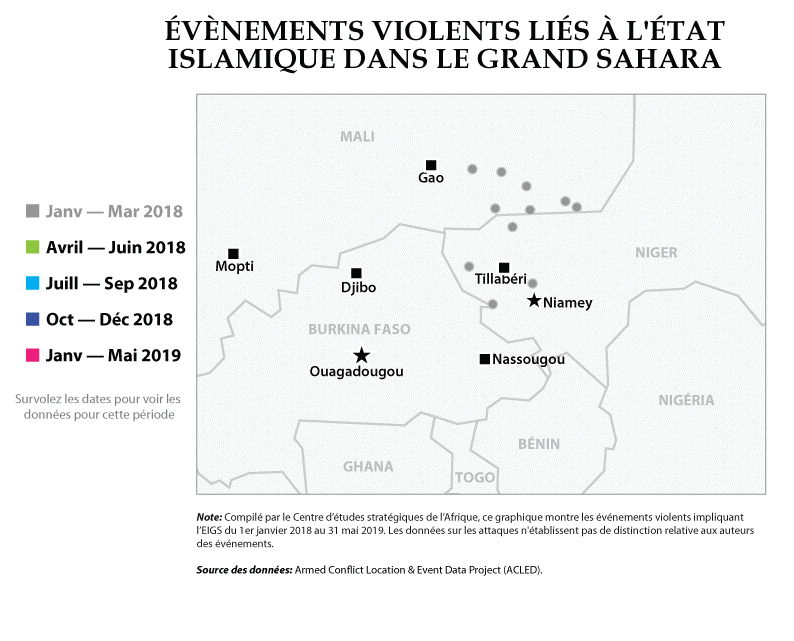

The EISS is distinguished by the geographical scope of its activity, which extends over some 800 km along the border between Mali and the west of Niger and about 600 km along the border between Burkina Faso and Niger. Almost 90% of the ISIS attacks occurred within a 100 km radius of one of these borders.

The EIGS has also become one of the most dangerous militant groups in the region. In 2018, it was associated with 26% of all incidents and 42% of deaths related to jihadist groups in the Sahel. At the current rate, the ISIS will be linked to more than 570 deaths in 2019, more than any other Sahelian terrorist group.

With the EISG breakthrough in the south, there is deep concern at the spread of jihadist violence, which is now threatening Benin, Togo, and Ghana. In early May 2019, two French tourists were kidnapped, and their guide killed in the Pendjari park in northern Benin, in an attack attributed to militant groups active in the region. Two French special forces commandos died during the rescue of the hostages in northern Burkina Faso.

As a result of the outbreak of violence in Burkina Faso, more than 100,000 refugees have been forced to flee their homes and about 1.2 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance. It is estimated that 2,000 schools are currently closed in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso, depriving 400,000 children of education.

The emergence of the EIGS

EISG was born in 2015 from the merger of pre-existing militant Islamist groups. The head of the ISIS is known as Adnane Abu Walid al-Sahrawi. He was born in 1973 in Laayoune, the capital of the disputed territory of Western Sahara. He is the grandson of a Sahrawi leader and his family is considered rich and has an extensive network of contacts. In the 1990s, Al Sahraoui’s family was moved to a Sahrawi refugee camp in Algeria. It was at this time that he joined the Frente Polisario, a Saharan national liberation movement aimed at ending the Moroccan presence in Western Sahara.

Little is known about the route followed by Al Sahraoui in the 1990s and 2000s. It has probably navigated between the nascent factions of the small terrorist groups that are gradually being established along the porous borders along the southern Maghreb and the northern Sahel. He also dealt with Tuareg militants of the Azawad movement in northern Mali.

It was at this time, in 2011, that the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO) was founded. Previously members of Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), the founders wanted to create a katiba (combatant unit) composed of Arab fighters, mostly from northern Mali. The ideology of MUJAO refers to notorious terrorists such as Osama bin Laden, former Taliban leader Mullah Omar, but also to historical figures such as Ousman dan Fodio (founder of Sokoto’s Caliphate, 1804–1903), El Hadj Umar Tall (1797–1864) and Sekou Amadou (who contributed to the founding of the Macina Empire from 1818).

Al Sahraoui is said to have joined MUJAO in 2012, including serving as spokesman for the e-group. On August 22, 2013, MUJAO, represented by al-Sahrawi and the Mulathameen Brigade – then led by Algerian activist Mokhtar Belmokhtar, himself heavily linked to AQIM – announced their merger. Al Sahraoui became one of the main leaders of the new Al-Murabitoune group.

In 2015, on behalf of Al-Murabitoune, Al Sahraoui unilaterally pledged allegiance to the leader of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS or Islamic State), Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. A few days later, Moktar Belmokhtar rejected this allegiance and reaffirmed al-Murabitoune’s loyalty to al-Qaeda. Al Sahraoui then broke with Al-Murabitoune and formed what is now known as EISGS.

Al Sahraoui’s claim was officially recognized by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi more than a year later, in October 2016, following significant operations conducted by the ISIS in Niger and Burkina Faso.

In its early days, EIS operated mainly around the town of Ménaka, in the Gao region of Mali, sometimes extending its area of influence to the Mopti region. Although most of the first members are Malians in the Gao region, the group’s activities quickly reached the Tillaberi region of Niger. In October 2017, the ISIS claimed responsibility for an attack near the village of Tongo Tongo in Niger, along the border with Mali. Five members of the Niger special forces and four American soldiers were killed in the attack. In 2017 and 2018, the group then extended its activities to the Gourma region in Mali and eastern Burkina Faso.

It is estimated that the EIS has a core of 100 fighters, but it relies on a network of informants and logistical support. In total, it could have between 300 and 425 members, including supporters in Niger and Burkina Faso. Unlike other militant Islamist groups in the Sahel, the EIGS does not seem to have developed a particularly strong and coherent doctrine or ideological discourse. Rather than winning popular support and establishing a determined area of influence and base, the EIS has focused more on expanding its scope. The focus on mobility could explain why, despite a very limited number of combatants, it has evolved and remained active within the borders of three countries. With the aim of harassing and severely testing the limited number of security forces deployed to patrol these large border areas.

Despite its formal separation from the Al Qaeda network in the Islamic Maghreb, the EISGS continues to collaborate with AQIM-affiliated groups. The EIS therefore looks like a branch of AQIM, the organization from which it comes. Although it relies on the “EIGS” label to increase its visibility – the Islamic State (ISIS) with a perception of a powerful global network – in fact, the group operates according to its own organizational structures, with its own goals and resources.

A group that constantly adapts to the local environment

Like other extremist groups such as the katiba Macina, the EIGS has exploited the grievances of marginalized communities to recruit, in particular (but not exclusively) targeting young Fulani. The lack of economic opportunities, the sense of social downgrading and the need for protection against cattle rustling all seem to have been major factors in the decision to join the EIGS. For example, in the Tillaberian region of Niger, even in the absence of substantial financial resources from extremist groups such as the ISIS, membership of an extremist group often seems to be associated with higher social status. According to a local silly leader, “Having weapons confers a certain prestige: village youths are very much influenced by young armed bandits who drive on motorcycles, well-dressed and well-nourished. Young pastoralists envy them a lot by admiring their appearance.”

When it considers it to be profitable, the group does not hesitate to feed ethnic divisions to strengthen unity and cohesion among its members. In June 2017, Al Sahraoui threatened to attack the people of Tuareg if the pro-government Tuareg militias such as the Tuareg Group, such as the Tuareg Imghad and Allied Autodefense Group (GATIA) and the Movement for Salvation of Azawad (MSA), did not deny the governments of Mali, Niger, and France.

“The EISS discourse is also highly scalable, with content changing depending on what is perceived as being the most popular in local communities. ”In 2017 and 2018, the ISIS carried out this threat, organizing several attacks on camps, markets and nomadic villages of Malian civilians, targeting mainly the Tuareg. MSA and GATIA combatants responded, killing Fulani herders and helping to exacerbate tensions between Tuareg and Fulani in the Liptako region. In February 2018, Tuareg militias, members of the Platform coalition linked to the Malian government, launched a joint offensive against the ISIS in the region of the three borders between Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso. The campaign, along with the strikes by Operation Barkhane, reduced the ability of the ISIS to operate along the border area, but also increased tensions between local communities. In April 2018, the EISA reportedly orchestrated the massacre of 40 Tuaregs in the Dausahak tribe. This type of intercommunal retaliation continues.

The EIGS frequently targets government officials in its attacks. In 2018, the group claimed the murder of the mayor of the commune of Koutougou because he worked “with the armed forces of Burkina, for the crusaders”. Since 2018, the EIGS has also repeatedly targeted schools, with devastating effects. More than 1,100 schools have been closed in Burkina Faso as a result of threats, attacks and killings of teachers and administrators.

The EISS discourse evolves according to the localities in which it is located, willingly exploiting grievances against the government if it considers that activating the ethnic divide is irrelevant. For example, after provoking clashes between the Fulani and the Tugors in Mali, the ISIS convinced some Peuls in Niger that the enemy was “not really the Tuareg, but the state.” For example, this narrative axis took the form of a raid on Operation Barkhane in January 2018. On 14 May 2019, jihadists attacked a high-security prison in Kutuukale, 45 km north of Niamey. Niger soldiers, launched in pursuit of terrorists, have been ambushed near Tongo Tongo, not far from the Malian border. About thirty Nigerian soldiers perished in this ambush that the EIS claimed, calling it an “attack on an apostate army”.

What are the answers to the EIGS?

Despite rumors that Al Sahraoui was injured in 2018 and forced to retreat from clashes with the Tuareg militias, the pace of EISGS attacks has not slowed down. However, military pressure on the group has increased. Operation Barkhane has increasingly targeted members of the ISIS, imposing several successive military defeats. In May 2018, the US placed the ISIS on the foreign terrorist list, and Al Sahraoui was named a global terrorist by the US State Department. The G5 Sahel Joint Force, established in 2017, aims to combat jihadist groups in border areas. However, the operationalisation and deployment of this force is still ongoing.

In August 2018, Sultan Ould Bady, Malian leader of Katiba Salaheddine and an ally of EISGS, surrendered to the Algerian authorities under pressure from the fight against ISIS leaders. Later that month, Barkhane announced that Mohamed Ag Almouner, one of al-Saharan’s most important lieutenants who allegedly orchestrated the attack on Tongo Tongo in 2017, had been killed in a raid. Nevertheless, the EIS has shown resilience.

In Burkina Faso, the security apparatus had to adapt to the sudden rise of the activity of ISIS and other terrorist groups. In the view of many observers, former President Blaise Compaoré would have negotiated non-aggression pacts with jihadist groups in the region in an attempt to protect Burkina Faso from attacks. Its hasty departure in 2014 caused major confusion within law enforcement agencies, requiring a reorganisation. In October 2017, a National Security Forum was launched by the new President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré to reform and reorganize the security sector.

In June 2017, a three-year programme of emergency funds of CFAF 455 billion (around 778 million) for the Sahel region of Burkina Faso was set up with the aim of improving local and administrative governance. Designed as a comprehensive response targeting the intersection of socio-economic and security challenges, the plan aims to finance new infrastructure, the expansion of public services (health care centres, police stations) and support for resilient agricultural projects. In 2018, around 265 million dollars were obtained for priority investments.

It is important to note that many Sahelian countries have already established bilateral and multilateral agreements to improve security cooperation. For example, Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger are all members of the 1992 Convention on Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters, the 1994 Convention on Extradition and the 2012 Charter for Judicial Cooperation of the Sahel.

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has also undertaken to pilot several initiatives aimed at strengthening cross-border cooperation in border management. Several international organisations, such as INTERPOL and the International Organisation for Migration, have also supported the authorities in Burkina Faso by launching border management and control programmes and by supporting the establishment of more effective systems for the collection and management of police information.

Although promising in their holistic approach and regional scope, the impact of these initiatives often remains modest due to the limited human, financial and institutional resources. These initiatives will therefore need to be strengthened and supported in the long term. In the meantime, maintaining pressure on the EISGS will require further strengthening local, national, regional and international alliances along the borders where the group has prospered.

Complementary resources

- Centre d’Etudes Strategic de l’Afrique, “Overview of Regional Security Responses in the Sahel”, Infographic, 5 March 2019.

- Pauline Le Roux, “Le Centre du Mali facing the terrorist threat”, Éclairage, Centre for Strategic Studies of Africa, 25 February 2019.

- Centre for Strategic Studies of Africa, “The Complex and Growing Threat of militant Islamist Groups in the Sahel”, Infographic, 21 February 2019.

- “Islamic activism in Africa”, African Security Bulletin No. 23, Centre for Strategic Studies of Africa, November, 2012.

- Helmoed Heitman, “Optimizing the Structures of the African Security Forces”, African Security Bulletin No. 13, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, May 2011.