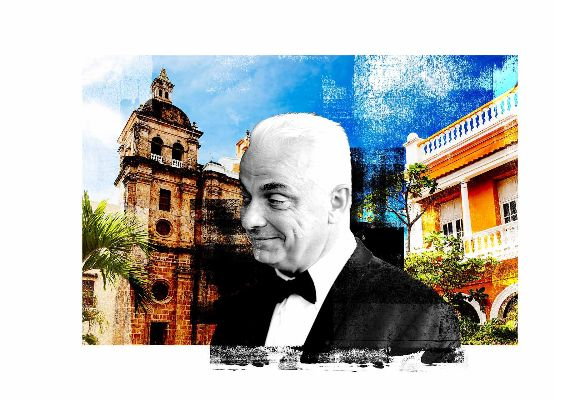

Henri De Croÿ was accused of masterminding a scheme that hid hundreds of millions from tax authorities on behalf of rich clients in Europe. Reporters found him in Cartagena, busy investing money in a series of luxury properties.

He once walked the halls of global financial institutions and hobnobbed with Europe’s elite, but today the Belgian prince and disgraced banker Henri de Croÿ has reinvented himself as an affable Colombian hotelier.

Ditching the suit and tie of a high-flying financier, he was spotted recently in leather moccasins and a loose button-down shirt in the tastefully-decorated lobby of one of his Cartagena hotels –– far from the prying eyes of European authorities investigating him for tax evasion and money laundering.

A descendant of one of Europe’s oldest aristocratic families, De Croÿ is under investigation for allegedly masterminding a scheme that hid hundreds of millions from tax authorities on behalf of scores of rich clients. Authorities in three European countries launched probes in the wake of the “Dubai Papers,” a leak of about 200,000 internal documents from De Croÿ’s group of companies, Helin Group, first published by the French magazine L’Obs in 2018.

L’Obs shared the Dubai Papers with reporters at OCCRP’s Colombian media partner, Cerosetenta, who had already obtained exclusive information about De Croÿ’s properties in their country. Using the leaked documents, and Colombian property registration records, they found that the prince has quietly built a luxurious real estate fiefdom on the country’s northern Caribbean coast.

The discovery could have legal repercussions, according to a lawyer representing two clients suing De Croÿ in Switzerland to regain a total of about 7 million euros they say he “mismanaged” by transferring it to an account in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which he did not control. She said the UAE has frozen his local assets, and her clients are now trying to get their money back.

“He hides his assets very well,” said the lawyer, Sonja Maeder Morvant. “He even denies being the owner of his chateau in France,” she added, referring to the Château d’Azy, a neoclassical villa built in 1846.

“Before the Swiss justice system, he presents himself as someone who now has little to no financial resources.”

Regardless of such claims, and despite the European investigations, De Croÿ and his family members have accumulated properties estimated to be worth at least $16 million in and around Cartagena.

They own four mansions in the city’s old town, two of which have been converted into boutique hotels, and one into an event venue. Another of the mansions awaits renovation. They also have a high-end resort on a private beach on the peninsula of Barú, about 50 kilometers by road from Cartagena’s old town.

De Croÿ’s Swiss lawyer, Grégoire Rey, said in an email to reporters that the funds used to buy the Colombian properties have “nothing to do with” funds that have been subject to litigation by former clients of Helin.

He said reporters were acting on “knowingly biased” information, with the aim of suggesting that Helin client money was “used for private purposes.”

The Black Prince

In the 2010s, De Croÿ earned the nickname “Black Prince” in the Belgian press when he was at the center of one of the country’s biggest-ever tax fraud cases. De Croÿ was accused of funneling the money he managed for clients into offshore firms. With relatively little left in their regular accounts to declare, the clients escaped paying about 75 million euros in tax, according to Belgian media reports.

A Belgian court sentenced him in 2012 to a three-year suspended prison term, according to media reports. He appealed and was acquitted in 2015.

But three years later, when the Dubai Papers emerged, documents from inside De Croÿ’s Helin Group — including emails, voice messages, accounting records, and bank transfers — showed he had expanded his money management scheme to clients far beyond his native Belgium. The leak cast doubt on De Croÿ’s claim, made in a 2018 interview with the Swiss newspaper Le Matin, that he had only engaged in legal “tax optimization.”

After the Dubai Papers bombshell, several former Helin clients in Switzerland launched a complaint for breach of trust and mismanagement. Swiss prosecutors began investigating De Croÿ for money laundering in 2018, and in 2019 both Belgian and French prosecutors began their own probes into his affairs.

“There is an ongoing investigation regarding money laundering and tax fraud, and we are cooperating with Belgium and Switzerland,” French financial prosecutors told Cerosetenta.

De Croÿ has been tied to Colombia for about three decades through his wife, María del Socorro Patiño Cordoba, who was born in the small, southwestern city of Popayán.

Patiño and De Croÿ first crossed paths in London, where he was working in banking, a career that would take him to the financial capitals of Hong Kong and Luxembourg. They married in 1994.

The couple were known to throw sumptuous receptions at their French estate, which sprawls over more than 40 hectares, while maintaining their primary residence first in the U.K. and later in Switzerland.

Slowly, the family’s connection to Colombia grew. In 2002 –– during the period he was later suspected of running the tax-evasion scheme –– De Croÿ was granted a Colombian passport.

Eight years later, as the prince faced Belgian authorities in court, Patiño gave a sworn declaration at her country’s consulate in London, letting them know she was shipping a container of furniture from the family’s French estate to Colombia.

“We wish to take up residence in Cartagena,” she wrote in a message included in the Dubai Papers. (She was not investigated in the Belgian tax evasion case, and there is no evidence she has ever been linked to any of the other investigations involving her husband.)

As De Croÿ fought tax evasion and money laundering charges in Belgium, he and his wife were busy building a new life on the Colombian coast, where they had bought their first property in 1997 and would acquire three more in the quaint old town of Cartagena and the nearby tropical area of Baru between 2004 and 2008.

In 2012 –– the same year a Belgian court reportedly convicted De Croÿ –– the couple changed the status of one of their Cartagena properties from residential to commercial; two others were re-classified as commercial properties in 2015.

By the time De Croÿ’s conviction was overturned in 2015, he was in the hotel business. The couple had renovated their Cartagena properties into three hotels that brought in about $300,000 in revenue that year, leaked records show. They would go on to buy another building suitable for a hotel in 2016. Together, these properties form a mini-chain of hotels called “Casa Córdoba.”

“The Casa Córdoba Resort group offers you the best of both worlds, Cartagena de Indias and Isla Baru” the chain’s website promises. “In the walled city we have two houses that will make you travel through time…. Then you will have the possibility of making a visit full of magic in Isla Baru.”

The Dubai Papers show that the couple paid for their final Casa Córdoba property in late 2015 and 2016 using money sent directly from Helin.

At first, Helin transferred money for the purchase to Patiño’s Colombian bank account, with a bookkeeper for the company noting the reason as “funds for the new property.” But the couple was apparently advised to send back the funds and purchase the property through a company, according to a copy of a fax in the Dubai Papers.

“They advised us to buy the property through a company instead of doing it in the personal name of María del Socorro Patiño Córdoba,” the fax said.

It concluded that she should transfer the funds back to Helin, “rather than risk being the victim of an overzealous public servant, to put it mildly,” it read.

The couple ended up making the purchase using Ethical Tourism Limited, a company controlled by Helin International, but whose sole shareholder and legal representative was Patiño.

De Croÿ’s lawyer acknowledged that Helin sent funds to buy the property, but he said this was family money under management by Helin. He said De Croÿs had a trust fund containing 6 million euros that were kept in the same bank account also used for Helin client funds. However, he insisted this account was totally separate from the money Helin’s former clients were trying to reclaim, which was held at a different bank.

“The family funds were held in a “CARTHAGENA TRUST”, incorporated in 2000 with some 6 million euro,” he wrote in an email.

“While the custodian banks have changed, the trust’s holdings have never (!) varied until this 2016 real estate investment.”

The De Croy Links to Casa Córdoba Properties

The Colombian properties that make up the Casa Córdoba hotel chain were purchased through a shell firm in the British Virgin Islands (BVI) or the UAE, where strict corporate secrecy laws allow company owners to remain anonymous. (De Croÿ’s Helin Group was based in the Emirate of Ras Al Khaimah.)

But while De Croÿ’s name does not appear on the titles of the Colombian mansions, there is extensive evidence linking him and his wife to the properties, including accounting documents showing the couple was involved in hotel operations.

Another document obtained by reporters shows that the company that owned one hotel gave Patiño free use of the property for more than 10 years. Patiño is also the legal representative of the company that manages the hotels, and the owner of a Colombian bank account that appears in payment instructions for tourists who want to book a room at a Casa Córdoba property.

Each of the shell companies that own the Colombian properties list a Helin company as its agent or sole shareholder. In addition, the companies list three directors who also direct other companies linked to the Helin Group.

Three months after the Dubai Papers broke, potentially exposing assets connected to Helin Group, the properties were purchased on paper by two Panamanian firms that had recently been registered. But those firms are also connected to De Croÿ, suggesting that the true ownership has not changed.

The timing of the Colombian purchases, most of which were made when De Croÿ was being investigated for running the tax fraud scam, raise the possibility that funds connected to the scandal were funneled into Colombian properties.

1997 –– De Croÿ and Patiño buy a sprawling 928-square-meter colonial-era house in Cartagena. The payment of $254,000 is transferred from a BVI company called Collwether Inc. They renovate the mansion, which is today the Hotel Casa Córdoba Estrella.

2004 –– They purchase a 185-square-meter house for $189,730, paying through the BVI company Fellaya Investments Ltd. The property is now the Hotel Casa Córdoba Román.

2007 –– The couple pay $240,819 for over 12,000 square meters of beachfront on Barú island using the BVI firm Lalou Property Corp. The property is now the Hotel Casa Córdoba Barú, where cabins go for $230 a night.

2008 –– They buy another colonial-era house in Cartegena’s old town, using the UAE company Colombe Ltd. The purchase price was $471,758. Today it is Casa Córdoba Cabal, a 600-square-meter events venue.

2016 –– The prince and his wife add the final piece to their Cartagena portfolio: a dilapidated 1,400-square-foot mansion that occupies half a block of the old town, called Casa Cuartel. The property cost $1.6 million, paid through a UAE company called Ethical Tourism Limited which lists Patiño as the main shareholder. The couple plan to transform the property into a 30-room hotel.

Secret Transactions

The acquisition of the Casa Cartel was not the only time that funds from Helin were moved into Colombia.

Accounting records from the Dubai Papers reveal other methods De Croÿ and Patiño used to avoid scrutiny from banks or financial regulators, while moving at least $1.3 million from Helin Group companies into Colombia between 2011 and 2017.

“He explained …that he had a bank in Dubai, and that this card was from that bank and he was sending … the money through there.”

– Ex-employee

The couple used prepaid debit cards loaded with funds from Helin Group companies to make thousands of withdrawals from cash machines in Colombia. Records from 2011 and 2012 show that in some cases, they visited ATMs over 10 times a day, maximizing the amount they could withdraw.

Juan Ricardo Ortega, former director of the Colombian tax authority, said making “micro-withdrawals” like this was a common money laundering tactic that should “raise some alarm bells” among Colombian financial police.

De Croÿ kept meticulous records of at least six prepaid cards, which were loaded with almost $240,000 between January 2015 and June 2016.

“He explained … that he had a bank in Dubai, and that this card was from that bank and he was sending … the money through it,” said an ex-employee of De Croÿ, who asked to remain anonymous. “Ninety percent of the business was handled with credit cards.”

“The use of this type of card is common in money laundering schemes,” said Ortega, former director of the Colombian tax authority. “These cards can be sent anywhere in the world by mail and are anonymous.”

Records show that another card registered under De Croÿ’s name at the infamous Tanzania-headquartered bank FBME — which was shut down in 2017 for alleged complicity in money laundering and terrorism financing — was used 1,370 times in less than two years, starting in 2011. Over $540,000 was withdrawn that way.

De Croÿ and Patiño also moved money via wire transfers, with four accounts in Colombia receiving over $543,000 between July 2016 and November 2017.

The money was shifted via at least 18 transfers from a U.K. company called European Management Distribution Limited, which at the time had one shareholder –– Patiño. The Dubai Papers show some of the transfers were ordered by “A3,” which is an alias for De Croÿ.

When the Dubai Papers broke, the couple appear to have taken extra measures to hide their assets, Panamanian corporate registry documents show.

Two Panama companies, Falur Corp. and Persoc Group Inc., were created in November and December 2018, just months after the story emerged. The people behind the companies are associated with De Croÿ, suggesting that he masterminded the move.

On a single day in December 2018 and in the same notary’s office, just a few days after its incorporation, Persoc bought three Cartagena mansions for a total of $2.3 million, well below their commercial appraisal. At the same time Falur Corp. acquired another property for the low price of $368,000. Finally, in May 2019, Persoc acquired the beach resort of Casa Córdoba Baru for a paltry $55,900.

Falur Corp’s director is Ricardo Vélez Pareja, a Cartagena lawyer. His son, Ricardo Vélez Benedetti, helped De Croÿ scout properties in Cartagena, and had power of attorney for several Colombian companies linked to the prince. A lawyer like his father, Vélez also represented De Croÿ’s wife in a lawsuit in Colombia. Persoc’s founding director is listed as María Ximena Montón Blanco, who holds positions in several De Croÿ companies linked to Helin. (OCCRP has uncovered no evidence that the Velezes or Montón committed any wrongdoing.)

Despite these apparent efforts, the prince’s Colombian affairs may soon come under further scrutiny.

Maeder, the lawyer representing De Croÿ’s alleged victims who are chasing funds sent to the UAE, said she may yet turn to other avenues: “If we are unable to recover the assets of our clients in the Emirates, we will seek redress directly from the person responsible for their loss.”