Introduction

A main element in the current economic and financial crisis in Lebanon is its energy crisis. The Lebanese people have been hit hard by the accelerated devaluation of the Lebanese pound and the fuel shortage; many lost their life savings in the recent collapse of the country’s banking system. Thus, the prospect of exploiting the potentially rich offshore natural gas fields appears to be a golden opportunity.

However, some of these natural gas fields are also claimed by Israel, and the decade-long U.S.-brokered Israel-Lebanon negotiations on the issue are deadlocked. This is due not only to the dispute over economic interests, but also to Lebanon’s political hesitations to engage in negotiations and cooperation with Israel.

Recent developments, however, suggest that there may soon be a breakthrough in this political impasse.

The Economic Crisis And Failed Solutions

In a June 10, 2022 interview on Hizbullah’s Al-Manar TV, Brig.-Gen. (ret.) Marwan Charbel, former Lebanese interior and municipalities minister, acknowledged before a live audience that despite his pension as a former cabinet minister, and despite his high rank in the military, he could not afford to connect to Lebanon’s main power grid and had had to dismiss his servant because her wages, paid in dollars, amounted to his entire pension.[1] This is a reflection of the severity of Lebanon’s economic situation.

In an attempt to resolve energy crisis, Lebanon has signed agreements for importing natural gas from Egypt and electricity from Jordan. However, these resources must, due to geography, go through either Israel or Syria to get to it. Israel is obviously not an option; at the same time, Syria is under international sanctions. Therefore, Cairo and Amman are waiting for American assurances that they will not be penalized if they send gas and electricity to Lebanon through Syria. So far, there have been no such assurances, and it is not certain that they will.

Hizbullah’s recent efforts, hyped by media, to truck fuel in from Iran have turned out to be nothing but a gimmick. Other Iranian proposals to provide a more comprehensive solution have been rejected by Lebanon, which fears the U.S. sanctions on Iran.

Timeline Of The Main Developments In The Negotiations

Under the 1982 UN Convention of the Law of the Sea, a country can declare an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extending 200 nautical miles from its coast. In an EEZ, a country has the sovereign right to extract natural resources, but no sovereignty over the surface waters, which remain international. The Israel-Lebanon dispute over the offshore gas fields is rooted in an overlap between the two countries’ claimed EEZs.

The following is a timeline of the main points in the development of the negotiations:

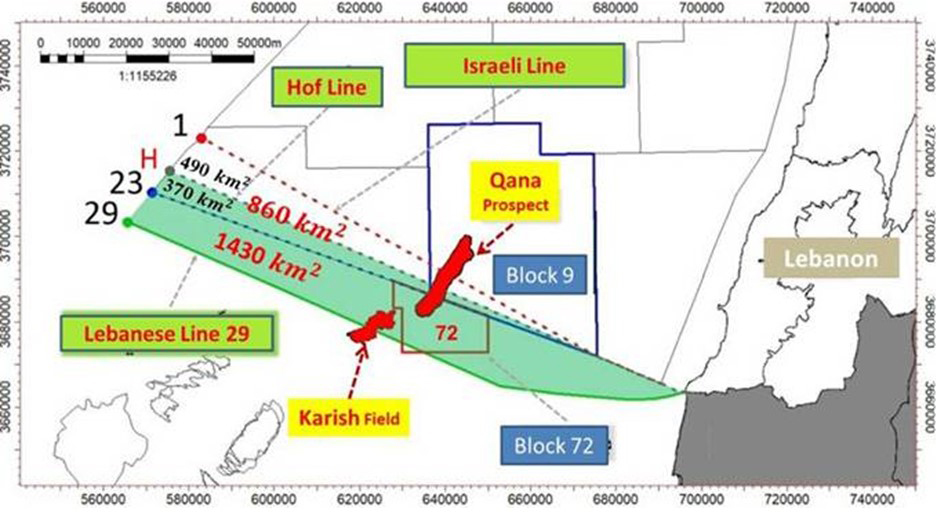

2007 – Lebanon and Cyprus sign an EEZ agreement. The agreement determined Line 23 (see above map) as the maritime border between Israel and Lebanon. The agreement was ratified by Cyprus but not by Lebanon, for a variety of reasons.

2009 – The first gas fields are discovered off Israel’s northern coast. Several additional large fields will be discovered in coming years.

2010 – Israel and Cyprus sign an EEZ accord amending the Israel-Lebanon border from Line 23 to Line 1. Lebanon claims that it was not consulted, and Cyprus says that it did not have to consult Lebanon, since Lebanon had not ratified the 2007 Cyprus-Lebanon accord. In the Israel-Cyprus accord, 860 square kilometers that had been in Lebanon’s EEZ under to the 2007 Cyprus-Lebanon agreement are now considered to be in Israel’s EEZ.

2011 – Lebanon issues Decree 6433 to the United Nations, claiming Line 23 as its southern maritime border. Later in the year, U.S. diplomat Frederick Hoff, who mediated between Lebanon and Israel, suggested what came to be known as the Hoff Line, offering Lebanon 55% of the disputed 860-square-kilometer triangle. The Hoff Line was rejected by Lebanon.

2012 – The Karish gas field is discovered in Israel’s EEZ, south of Line 23.

2017 – Lebanon signs contracts with international companies to explore Blocs 4 and 9 off its shore. Bloc 4 is found to be valueless, but the Qana prospect shows promising results in seismic tests. The Qana prospect is divided between Bloc 9, north of Line 23, and Bloc 72, which is in the now-disputed area between Line 23 and Line 29.

2020 – A study conducted by the Lebanese military suggests that the southern limit of Lebanon’s EEZ should be extended south from Line 23 to Line 29. This would bring most of the Karish field into Lebanon’s EEZ. Thus far, Lebanon has refrained from amending Decree 6433, although the document is sitting on Lebanese President Michel Aoun’s desk for signing.

February 2022 – According to media reports, U.S. envoy Amos Hochstein, who replaced Frederick Hoff, offered to resolve the dispute through a utilization agreement regarding the Qana prospect. According to this proposal, Lebanon would relinquish all claims to the Karish field, and in return, Israel and Lebanon would share the Qana prospect.

June 2022 – According to media reports, Lebanon told Hochstein that it would agree to relinquish claims to the Karish field in return for complete ownership of the Qana prospect.[2] Other reports suggested that Lebanese President Aoun had agreed to split the Qana gas prospect.[3]

Hizbullah And The Israel-Lebanon Negotiations

When Lebanon shifted the claimed southern boundary of its EEZ from Line 23 to Line 29, the negotiations came to a standstill. However, Lebanon has still refrained from officially amending Decree 6433 to the UN about its maritime borders. This appears to be an attempt by Lebanon to maintain some sort of open line of communication for a future solution.

Then, in early June 2022, the arrival at the Karish gas field of a floating production storage and offloading (FPSO) extraction vessel operated by the British-Greek company Energean rekindled fears of a Hizbullah attack on Israel’s gas facilities there. Hizbullah secretary-general Hassan Nasrallah and other Hizbullah leaders responded to the FPSO’s arrival with belligerent statements and threats. At the same time, they hinted that the organization was not going to carry out a surprise attack on Israel’s drilling operations, but that its “resistance” services would be offered the Lebanese government.

Hizbullah is in a pickle. While it is paralyzed by its ideology that rejects any negotiations or partnership with Israel, which it obviously does not recognize, it does not want to be perceived as the one thwarting the only project capable of rescuing Lebanon from its economic crisis.

Thus, Hizbullah’s official position, declared multiple times by Nasrallah and others, is that Lebanon should not wait for Israel’s consent and should start signing contracts and drilling in the disputed area – and that if Israel disrupts these efforts, Hizbullah will retaliate by disrupting Israeli drilling. In a May 2022 speech, Nasrallah said: “Let me reassure you that there are international firms that would accept [this]… I say to the Lebanese state and to the Lebanese people that you have courageous, powerful, and capable resistance force[s] that can tell the enemy – who is working day and night to drill and extract oil and gas from the disputed areas — that if you prevent Lebanon from doing this, we will respond in kind.”[4]

“No” To Joint Utilization, “Maybe” To Gas Field Swap

Hizbullah leaders claim that the path of negotiations is futile, especially when mediated by U.S. envoy Amos Hochstein, who is Israeli-born. In his speech in May, Nasrallah said, addressing “the Lebanese state”: “If you want to continue negotiating, go ahead, but… not with Hochstein, Frankenstein, or any other Stein coming to Lebanon.”[5]

However, Hochstein’s proposal for a utilization agreement for the Qana prospect – which would mean entering into a business partnership with Israel – prompted outright rejection. As Mohammad Raad, the head of Hizbullah’s Loyalty to the Resistance parliamentary bloc, said in February 2022, “They tell us that we can drill in the water, but it may turn out that you will need to share the gas field with the Israelis. No! We’d rather leave the gas buried underwater, until the day comes when we can prevent the Israelis from touching a single drop of our waters.”[6]

This approach frustrated Hizbullah’s main political ally, Lebanese President Michael Aoun’s Free Patriotic Movement, which is led by his son-in-law, Gebran Bassil. Bassil, who is a presidential candidate in the upcoming October election although he is under U.S. sanctions, called for pursuing a solution through negotiations and for bypassing nationalist obstacles.

Bassil said in February 2022 that when it comes to EEZs, sovereignty becomes irrelevant, and it is all about the economy.[7] Expressing support for a compromise solution based on Lebanon’s exploration of the Qana prospect, and even showing willingness to compromise on parts of the Qana propsect, he said: “It may be entirely ours or we will get a part of it, in a way that enables us to get the lion’s share of it… We should focus on the entire story – what we gain and what we lose… In any agreement, you win some and you lose some. In order to reach an agreement, both sides need to feel that they are gaining something… I support getting as much as we can, but we want to get to a point where we say: Okay. Where is the point that we can accept?”[8]

As mentioned above, in June 2022 the Lebanese government offered to Hochstein that it would relinquish claims to Line 29 and the Karish gas field in exchange for complete ownership of the Qana prospect. It is highly unlikely that this offer was delivered without a green light from Hizbullah, and this offer may be an easier pill for Hizbullah to swallow than Hochstein’s joint utilization proposal, since it would require no explicit collaboration with Israel.

Yet, several obstacles remain. For one, while the Karish field has been proven to have gas, Qana is still just a prospect, and despite promising seismic tests, only the drilling itself will determine the project’s economic viability.

In addition, according to media reports, Lebanon is demanding that Israel halt drilling operations in the Karish field until Lebanon begins drilling in the Qana prospect. Not only is Israel unlikely to agree to these demands – it would also have to make important concessions to allow such a deal to go through, since it still claims Line 1 as the northern limit of its EEZ (in accordance with its 2010 agreement with Cyprus).

Hizbullah And The Lebanese Government

Speculation in the media about a possible Hizbullah attack on Israel’s gas facilities was renewed when the Greek FPSO vessel arrived at the Karish gas field in June 2022. Hizbullah leaders have repeatedly stressed that they would only act at the behest of the Lebanese government. Deputy Hizbullah secretary-general Naim Qassem reiterated this in a June 6 interview with Reuters, saying: “When the Lebanese state says that the Israelis are assaulting our waters and our oil, then we are ready to do our part in terms of pressure, deterrence and use of appropriate means – including force.”[9]

But these reassurances did not impress eager Hizbullah loyalists in the media, such as London-based journalist Abdel Bari Atwan. Atwan pointed out that Hizbullah had not asked the Lebanese government for permission when it fought to expel Israel from southern Lebanon, or when it kidnapped Israeli soldiers in 2006 in a move leading to the Second Lebanon War. He added that Nasrallah’s June speech was an indication that the leader had already decided to attack the Israeli gas drilling facilities and start a war.[10]

It is noteworthy that Hizbullah, which is backed and funded by Iran and does its bidding, has not been called upon by its patron to act. Iran continues to refrain from engaging in a direct military conflict with Israel, despite opportunities to do so.

Conclusion

The Israeli-Lebanese EEZ negotiations have been faltering for over a decade, since the rejection of the Hoff compromise in 2011. Another major setback came in 2020, when Lebanon suddenly moved the goalposts and shifted the southern boundary of its claimed EEZ to Line 29 in order to include Israel’s Karish gas field.

However, Lebanon’s economic collapse has led some Lebanese leaders to reconsider its inflexible stance, and President Aoun’s decision to refrain from officially amending Decree 6433 with the UN – as well as Gebran Bassil’s statements about the need for compromise – are indications that that Lebanon may back down from its maximalist Line 29 demands. It should be noted that according to some reports, President Aoun agreed, in a meeting with Amos Hochstein, to the splitting of the Qana prospect with Israel. Also, a report in the Israeli financial daily Globes stated that this Lebanese concession was not put in writing, but was delivered to Hochstein in person “out of concern that the compromise would be leaked to Hizbullah.”[11]

A Lebanese return to Line 23 and Lebanese acceptance of sharing the Qana prospect are highly unlikely. For Hizbullah, and probably for others in Lebanon, U.S. envoy Amos Hochstein’s proposal of going into business with Israel and jointly drilling for gas at the Qana prospect is a non-starter. However, a gas field swap may be a viable solution for Hizbullah, since it could to breathe some life back into Lebanon’s economy without requiring Hizbullah to make any ideological compromises. Hizbullah has indeed taken a backseat in the negotiations – but it is unlikely that any proposal was extended to Hochstein without its consent. In any case, since the exchange in the Aoun-Hochstein meeting was not put in writing, it is completely deniable.

Meanwhile, Israel’s position is still unknown. Israel has no interest in the collapse of the Lebanese economy, but such a compromise would require it to give up its share of the Qana prospect, which it may or may not be willing to do.