Investors are on the edge of their seats for any sign that Fed central planners will someday “pivot” to cutting interest rates, instead of raising them. They forget that recessions and major stock bear markets have occurred after the Fed started cutting rates and the yield curve spread shifted from negative to positive.

The Fed has been very clear that they now have “that old-time religion” of former Fed chairman Paul Volker to fight the inflation they created when they increased the money supply by 40 percent after the covid panic in 2020. They now say they need to see inflation clearly slowing to their arbitrary 2 percent target (which cuts the value of the dollar in half every thirty-four years) before they will even consider cutting interest rates. They claim they learned the mistake of the 1970s that cutting rates too soon before the inflation battle is won likely prolongs the misery of high inflation.

The Trillion-Dollar Question

The trillion-dollar question is: when will inflation clearly slow toward 2 percent?

No one can say for sure, particularly Fed bureaucrats who have proven their inability to predict anything. But a recently published paper by investment research firm Research Affiliates attempts to answer this question by looking at prior historical periods of high inflation. This paper, titled “History Lessons: How ‘Transitory’ Is Inflation?” Analyzed all cases where inflation rose above 4 percent in fourteen developed countries from January 1970 through September 2022.

History Lessons for the Fed and Investors

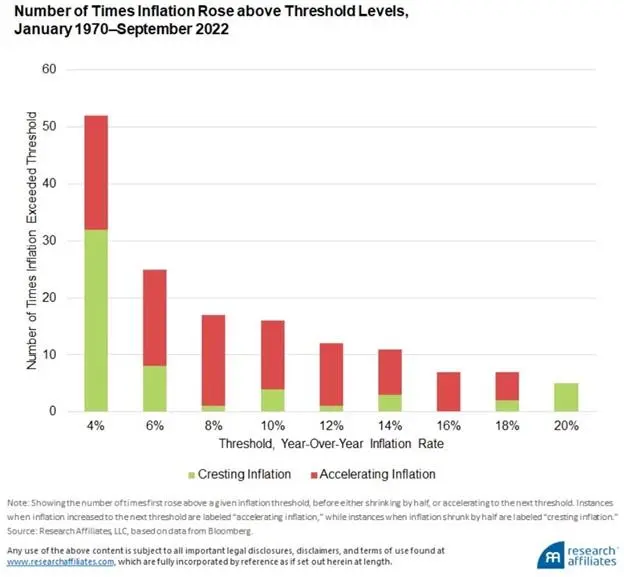

During this period, inflation rose above 4 percent in these fourteen countries. In six of those instances, inflation proceeded to rise over 20 percent fifty-two times. More than 60 percent of the time, inflation did not exceed 6 percent. But if inflation rose over 8 percent, as happened in the US and most of Europe this year, inflation rose to 10 percent or more over 70 percent of the time.The following graph shows the number of times inflation exceeded a given level, with the green shading showing the number of times inflation peaked at that level and the red shading showing the number of times inflation accelerated to the next level.

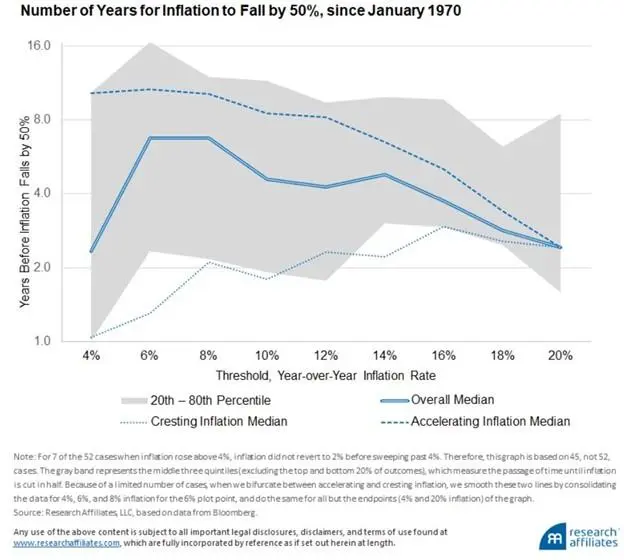

The graph below shows the median number of years it took for inflation to fall in half after it reached a given level. The shaded area shows the range for 60 percent of the outcomes, excluding the top 20 percent and bottom 20 percent.

This graph shows that after inflation rises above 4 percent, 20 percent of the time it falls to 2 percent within a year, but 20 percent of the time it takes 10 years to fall back to 2 percent. The median time is 2.5 years. As the authors of the study wisely ask:

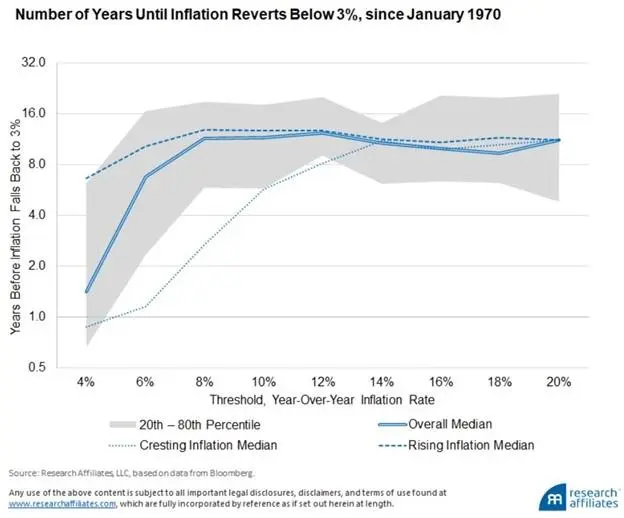

When inflation was already crossing 4 percent in April 2021 (2 percent of which was in the prior three months, which was an 8 percent annualized rate!), what were Powell and Yellen thinking in declaring the inflation transitory? Should we consider a median expectation of 2½ years to revert to a 2 percent inflation rate as transitory?If inflation rises above 6 percent, it takes a median of ten years to fall back to 2 percent. As shown in the chart below, with inflation of 8 percent to 20 percent, it takes a median of nine to twelve years for inflation to fall below 3 percent. But, as the authors caution: “This lengthy period may actually be understated because of the handful of cases missing from our dataset in which inflation has failed to return to 3 percent, to this day.”

Since US inflation rose above 6 percent a year ago and above 8 percent eight months ago, history says the median number of years for inflation to fall below 3 percent is ten years, with a 60 percent percentile range of six to nineteen years! Clearly, the Fed and investors are not prepared for such a possibility.

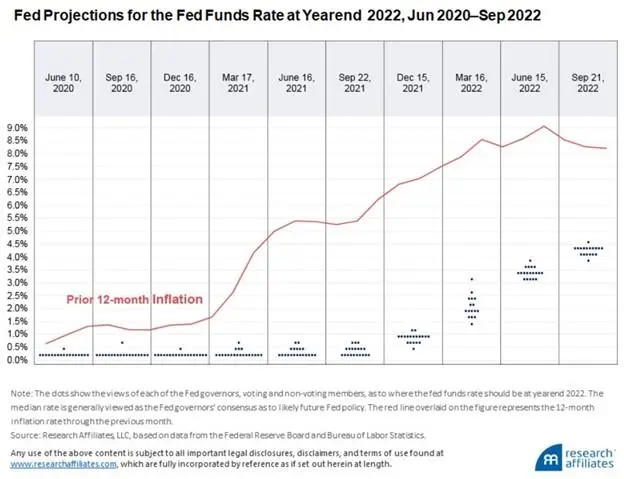

As shown in the chart below of the Fed’s projections of the federal funds rate, after inflation was already near 7 percent a year ago, the Fed still expected the federal funds rate at the end of 2022 to only be 0.88 percent! The federal funds rate is now 3.75 percent to 4.00 percent and the two-year Treasury rate they follow is at 4.36 percent. Why does anyone listen to these failed central planners about anything?

US Inflation History Supports This Conclusion

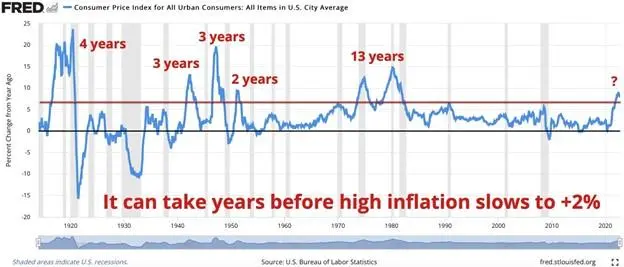

The chart below shows US inflation since the Fed was created in 1913. The US dollar has lost 97 percent of its value since then, as cumulative inflation has been over 2900 percent. The horizontal red line shows five periods prior to now when inflation rose well over 7 percent. The first instance was caused by money printing for World War I, which resulted in the highest inflation rates in modern US history at over 20 percent. It took about four years for inflation to return to 2 percent after that. Then there were three instances during the 1940s and 1950s when it took two to three years each time for inflation to return to 2 percent.

The longest-lasting bout of inflation occurred during the 1970s and early 1980s, when it took thirteen long years for inflation to return to 2 percent. And to do that, Fed chair Paul Volker had to raise the federal funds rate over 15 percent for two years to break inflationary psychology and it still took six years for inflation to fall to 2 percent after he started.

Does the current Fed chair, Jay “Wrong-Way” Powell, have the fortitude to do that in the face of a recession?

Federal Bureaucrats Are to Blame for Our Falling Living Standards

The authors of this study concluded by blaming Federal monetary and fiscal bureaucrats for this colossal mistake that is lowering our living standards:

It was a mistake for the Fed to declare inflation transitory when it was rising rapidly and when history tells us that, even at a relatively modest 4 percent rate, it often is not transitory. The Fed inflicted serious damage, both to the macroeconomy and to its own credibility, by following a too-easy policy for a dozen years and then continuing its transitory messaging as inflation lofted past 6 percent, then 8 percent. The same messaging continues today, albeit in different words. . . . Is it possible that inflation will recede to 4 percent and then to 2 percent in the coming year or two? Of course it’s possible! History says it is unlikely. . . . Our fiscal and monetary policies have done far more harm than good in recent years. . . . We perceive a resistance to alternative views, in both fiscal and monetary circles, a desire to create an echo-chamber of similar views, and a reluctance to learn from past mistakes. We are fools if we allow our hopes for a rapid dissipation of inflation to become our central expectation.Conclusion

Price inflation is caused by two factors: 1) money supply and 2) money demand, which is driven by inflationary psychology. Money supply growth has already slowed from 40 percent in 2021 to under 3 percent now. But money demand will depend on how confident the public is that Powell and his fellow government central planners will be aggressive in their fight against inflation, even with a recession likely having already started.

Based on history and Powell’s constant flip-flopping, it will likely be at least a year and could be a decade or more before inflation falls back to the Fed’s 2 percent target. People need to protect themselves from the lower living standards caused by high inflation rather than hoping government bureaucrats will rescue them.