Key points

- Alliances are usually temporary arrangements among states to counter—or “balance” against—a specific common threat. The United States’ Cold War alliances, by contrast, have become seemingly permanent.

- States tend to balance power when they face a major threat. Bandwagoning, by contrast, is a particularly poor option for states with the capability to put up a fight. When threatened, states tend to join forces in alliances rather than surrender their national survival to the whims of a more powerful aggressor.

- Alliances, however, entail costs and risks. These include the dangers of being drawn into war through entanglement and entrapment, the deleterious effect on deterrence by allies that neglect their defense by “free-riding,” and the moral hazard produced by enabling allies to act like “reckless drivers.”

- Over time, the United States has shifted from a deep skepticism of “entangling alliances” to a global network of security dependents that are treated as an end in themselves, rather than a means to an end. This posture has left the United States overextended, while encouraging allies to neglect their own capabilities and preparedness.

- The United States can and should significantly reduce its alliance commitments, particularly in Europe and the Middle East, where threats to the U.S. are remote and local powers can balance adversaries. In Asia, the United States should act as a backstop to the regional balance of power rather than a vanguard.

Alliances

Most alliances between states have historically proven temporary. Alliances usually begin and end in response to changing circumstances in international politics, the emergence and disappearance of common threats, and shifts in the balance of power.1 As the nineteenth-century British statesman Lord Palmerston famously said, “We have no eternal allies, and we have no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual, and those interests it is our duty to follow.”2

Yet the United States’ post-World War II alliances stand in marked contrast to this historical pattern. While alliances formed among other states between 1815 and 1944 lasted on average less than 10 years, post-war U.S. alliances, on average, have lasted more than 40 years—and are unlikely to end in the near-future.3 The United States’ leading role in providing security for Western Europe and East Asia—a product of the devastation wrought on those regions during World War II—was preserved even as states like Germany and Japan became among the most prosperous in the world. Despite a dramatic shift three decades ago to an unprecedentedly benign security environment following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the United States’ Cold War alliances were not disbanded—they were expanded. The seemingly permanent retention of these alliances is more striking given the United States’ long prior history of seeking to avoid entanglement in the affairs of other great powers overseas.

This paper will first explain the benefits of alliances, under what conditions they form, and why balancing behavior predominates. Next it will examine the costs and risks inherent to alliances, and why they can be liabilities as well as benefits. Last, it will assess the United States’ current alliances. In doing so, it will argue that the United States is overextended, that many of its allies can take on much or even all of the burden for their own defense, and that downsizing its overseas commitments would reduce the United States’ exposure to unnecessary risks and costs while preserving its vital security interests.

Alliance formation

Alliances are agreements between sovereign states to form a common defense against a mutual threat.4 These may include mutual or collective defense agreements between “treaty allies”—such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)—or agreements to cooperate against a specific common foe in war—like between the Allied powers during World War II.5 Alliances commit states to accept the costs and risks of war if one of them is attacked or threatened. Commitments to wage war in concert or on behalf of another can therefore only be justified if the threat posed by an adversary’s success outweighs the costs and risks of war, and if the security of an ally is vital to the security of one’s own state.

When a state or bloc becomes too powerful and threatening, alliances tend to form among other states to counterbalance it.6 Alliance formation is one of the fundamental means by which the balance of power is regulated and bids for hegemony—domination by a single state—are thwarted. Alliance formation is therefore sometimes referred to as “external balancing.”7 Alliances seek to pool sufficient resources to deter aggressors in peacetime and defeat enemies in wartime.

Alliances are held together by mutual security concerns and a shared perception of threat. Alliances are often formed between strange bedfellows that have differing regime types or state ideologies but are brought together by a common foe. During the Thirty Years’ War, the Dutch Republic, Sweden, and France all opposed the Habsburg dynasties of Spain and the Holy Roman Empire, despite having different religious affinities and forms of government. In the years prior to World War I, the relatively liberal states of Britain and France formed the Triple Entente with the most autocratic state in Europe, Tsarist Russia, to counter the rising power of Imperial Germany, which at the time was the only state among them with universal suffrage. During World War II, the capitalist United States and United Kingdom formed an alliance with the communist Soviet Union against the Axis Powers. During the Cold War, the United States developed an entente with communist China against the Soviet Union, even though China had previously been much more hostile to the idea of “peaceful coexistence” with the West than the Soviets.8

While the incentive to combine forces in the face of danger is strong, even among states that are not natural allies, it is not the only way states can respond. The following section looks in more detail at the strategies states can pursue in response to an emerging threat, and why it is that balancing tends to obtain over others.

The benefits of balancing

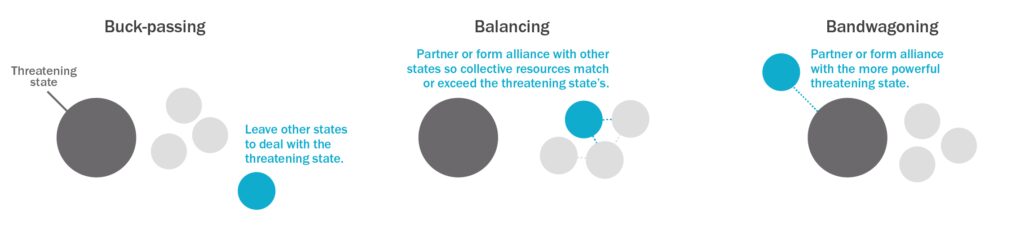

There are three fundamental strategies a state can pursue when faced with a major threat.9 The first is a “buck-passing” strategy, by which a state stands aloof as other states take on the costs, risks, and efforts required to balance against a rising adversary.10 Buck-passing is often a state’s first preference, especially before a threat manifests itself.11 Yet buck-passing can also, under some circumstances, make it more difficult to deter a war before the fact, so a threat can only be successfully countered through combat. States with more distant interests, lower threat perceptions, or insufficient resources will often pursue a buck-passing strategy unless or until they are compelled to balance. The United States, for example, pursued a buck-passing strategy in the early phases of both world wars, only to slowly grow more engaged and act as the “balancer of last resort.”

The second strategy, and the one most salient to alliances, is to balance. In the face of a serious threat, all states cannot simply pass the buck because there will be no one left to pass the buck to, and the result would be common inaction. Eventually, states which seek to remain independent and sovereign in the face of a more powerful threat are compelled to balance. Balancing can be both “internal,” meaning a state devoting more of its own domestic resources to defense, or “external,” meaning a state forming alliances.12 Balancing is often the second preference of a state, but survival is always the first priority. Therefore, when states are in a truly dire situation, they tend to balance. This general tendency towards balancing is largely responsible for the preservation of the structural condition of anarchy in the international system, and the infrequent achievement of regional, let alone global, hegemony by a single state.13 Modern examples of failed bids for regional hegemony include the Austrian and Spanish Habsburgs, Bourbon and Napoleonic France, Imperial and Nazi Germany, and Imperial Japan.14

The third strategy is to “bandwagon,” or to cut a deal and align one’s own policies with the preferences of a more powerful adversary in the hope of retaining some degree of independence and domestic autonomy. Bandwagoning is the least preferable of all options, not only because it circumscribes a state’s sovereignty under the best conditions, but because it can never be guaranteed that the stronger party will hold up their end of the deal. State A, for instance, may agree not to intervene in the domestic affairs of State B if the latter aligns their foreign policy with the former. Over time, however, State A may decide to influence or determine State B’s domestic policies, threaten to use force in order to impose its will, install a puppet government, or simply invade, occupy, or annex State B. Having chosen to bandwagon, State B will not have the independent means to resist.

Bandwagoning, therefore, is generally only pursued by weaker states with no capable and credible allies and thus no other choice. States that bandwagon are often referred to as being within the “sphere of influence” of a great power. Canada and Mexico, for instance, despite possessing relatively large territories, economies, and populations, have long accepted being within the United States’ sphere of influence. This has served to loosely constrain their sovereignty, as the United States wouldn’t allow either neighbor to become an ally or bulwark for a rival great power.

In the face of an aggressive prospective hegemon, therefore, neither buck-passing nor bandwagoning are optimal for the common good of all states under threat: buck-passing may allow an emerging threat to metastasize and grow more formidable, while bandwagoning leaves a state at the mercy of a more powerful state. In order to preserve their independence, states are often willing to accept the terrible costs of waging war. Combining with others increases the possibility either that war can be avoided by deterring an aggressor or that the allies can emerge victorious if war becomes inevitable.

Costs and risks of alliances

In some cases, an ally may be important enough that their defense constitutes a genuine strategic interest for another state, i.e. their defeat would significantly tip the balance of power in favor of an adversary. An example would be the United States’ commitment to defend the industrial centers of Western Europe and Japan during the Cold War in order to prevent the Soviet Union from accumulating enough industrial and military power to become a Eurasian hegemon.15 Yet while balancing is the best course in the face of an existential threat, alliances also entail significant costs and risks. Therefore, most states have historically been wary of maintaining permanent alliances, seeking instead to avoid entanglement, reduce the resources they devote to defense, and retain the ability to realign their policy as changing circumstances dictate.

Entanglement, entrapment, and chain-ganging

When allies commit to each other’s defense, they may make themselves hostages to another state’s policies or actions. “Entanglement” occurs when a state perceives an ally’s security as an end in itself, rather than a means to maintain one’s own security.16 In other words, the alliance becomes fetishized as a permanent inter-dependence of interests, rather than a temporary convergence of independent interests. This, in turn, can lead one state to fight for the interests of another as if they were their own. In the anarchic “self-help” world of international politics this can prove fatal, as states may put their own survival at risk to fight for peripheral interests.

The most important form of entanglement (the two terms are sometimes used synonymously) is “entrapment.” Entrapment occurs when a state feels compelled to defend an ally that has become immersed in a conflict, regardless of whether the state believes a war is in its own independent interests.17 A second-order form of entrapment, called “chain-ganging,” occurs when a single state in a multilateral alliance gets drawn into a fight and drags in all the others, just as a prisoner chained at the ankle to a line of fellow inmates will drag everyone else down if he falls off a railcar.18 The classic example is the leadup to World War I. As Kenneth Waltz put it:

If Austria-Hungary marched, Germany had to follow; the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire would have left Germany alone in the middle of Europe. If France marched, Russia had to follow; a German victory over France would be a defeat for Russia. And so it was all around the vicious circle.19

Notably, the Austro-Hungarian, Russian, German, and Ottoman empires did not survive the war—their regimes dissolved and their territory was carved up. Britain and France survived, but never fully recovered. The United States, which “passed the buck” until the war’s final act, was in the strongest position among the great powers at the war’s conclusion. This demonstrates how entanglement can endanger a state’s survival and power position, while maintaining a “free hand” can allow states with the ability to “pass the buck” to benefit in relative terms.

Credibility

In forming alliances, states often seek to deter an adversary from aggression. Deterrence requires convincing an adversary that the forces arrayed against them can either directly prevent them from achieving their goals by force or can impose sufficient costs to outweigh their expected benefits.20 While deterring an adversary and thus avoiding a war is generally preferable, credibly doing so requires the adversary to be convinced the states arrayed against it are willing and able to fight if necessary.

Some commitments are more credible than others. Commitments made by one state to another in excess of their capabilities are, in the words of the famous twentieth-century political commentator Walter Lippman, “insolvent.”21 Moreover, in order to credibly deter, the capabilities required to make a commitment “solvent” must correspond to strategic interests that are strong enough to demand the requisite investment in blood and treasure. It is therefore of paramount importance that the commitments a state makes to another’s defense reflect both its ability to make good on those commitments and a vital stake in the latter’s security. The more capable and resolute the state making the commitment is, the more credible the commitment will be, and the more credible the commitment, the more likely it will be to deter an adversary and avoid actual combat.

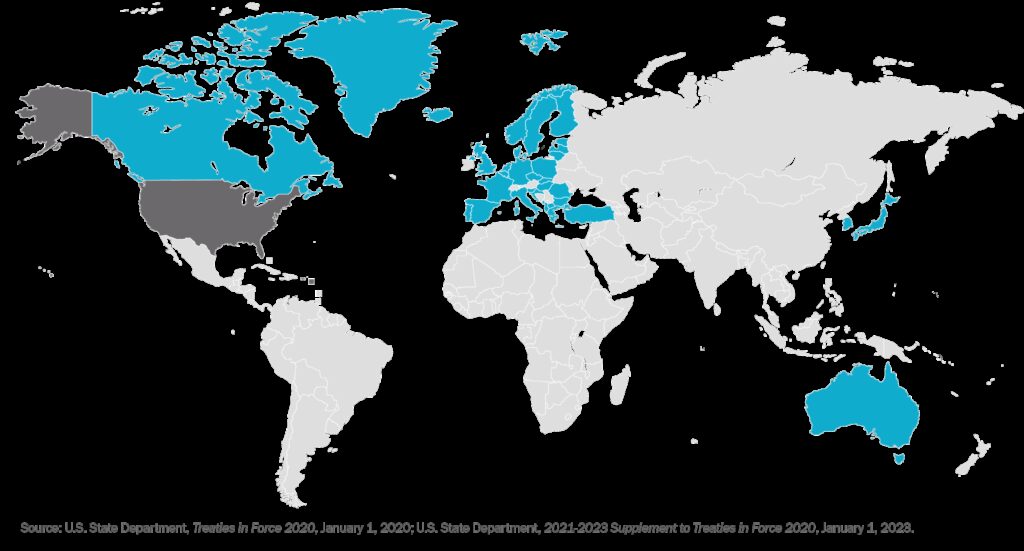

Credibility is particularly important with regard to nuclear weapons and extended deterrence. “Extended deterrence” is when one state commits to defend another in order to deter on their behalf. In the case of the United States and its allies, extended deterrence mainly refers to the United States’ commitment to use nuclear weapons to defend its allies if necessary, especially against another nuclear power.

Given the possibility that war between two nuclear states would lead to mutual annihilation, the commitment to initiate such a war to defend another state requires an adversary to find it plausible that the loss of, say, Germany or Japan would be vital enough to the existence of the United States to be tantamount to national suicide. This is a tall order: extended nuclear deterrence suffers from inherent credibility problems because it is difficult to convince an adversary you care as much about another country as you do about your own.22

Concerns over credibility can result in wars to demonstrate resolve, even in the absence of specific interests proportionate to the costs and risks of those wars. Such wars are driven by the fear on the part of one state that a failure to uphold commitments in the periphery will cause other allies to defect and bandwagon on the side of an adversary, or the adversary to doubt the state’s resolve and become emboldened to aggress against a more significant interest.23 This fear is at the core of one variant of “domino theory.”24 For example, despite many policymakers’ conviction that the United States’ Cold War security architecture would be fatally undermined if South Vietnam were not propped up by U.S. forces, the fall of Vietnam to the North caused no additional “dominoes” to fall; on the contrary, communist Vietnam soon found itself at war with both communist Cambodia and communist China.

If a state conditions its support for an ally, or signals it will not defend them, this may undermine the credibility of the alliance in the eyes of an adversary. It may also lead an ally to fear “abandonment,” the opposite of “entanglement.”25 An ally fearing abandonment might hypothetically decide the best course is to bandwagon with an adversary rather than place their hopes in an unreliable ally.26 Yet for the reasons stated above, bandwagoning is extremely dangerous, leaving the “bandwagoner” vulnerable to betrayal by a more powerful state.27 The unappealing nature of bandwagoning means that credibility tends to be less essential for reassuring allies than policymakers and commentators often believe.

Therefore, powerful countries (like the United States) do not have to be overzealous in reassuring their overseas allies they will not be abandoned in order to prevent them from bandwagoning with a local threat. On the contrary, assuaging allies’ fears too much may actually lead them to “free ride” and “drive recklessly,” which obstructs effective and durable balancing when it is needed.

Free-riding and reckless driving

If an ally is too confident in the credibility of another’s commitment to defend them, they may be encouraged to “free ride.”28 Free-riding is similar to buck-passing but occurs within an alliance rather than as an alternative to an alliance; indeed, it is made possible by a state’s commitment to another’s defense. If one state claims that another state’s security is vital enough that it is willing to risk national suicide to defend its ally, the latter state can pass many of the costs and risks of defending itself onto its patron.

Entanglement and free-riding are both closely related to another phenomenon called “reckless driving.” Reckless driving is essentially a form of moral hazard, or a perverse incentive for irresponsible behavior by one party based on the guarantee by another party to accept all the consequences.29 By agreeing to defend its allies, the United States may be encouraging them to act with less caution than they otherwise would if they alone were responsible for dealing with the consequences of their actions.

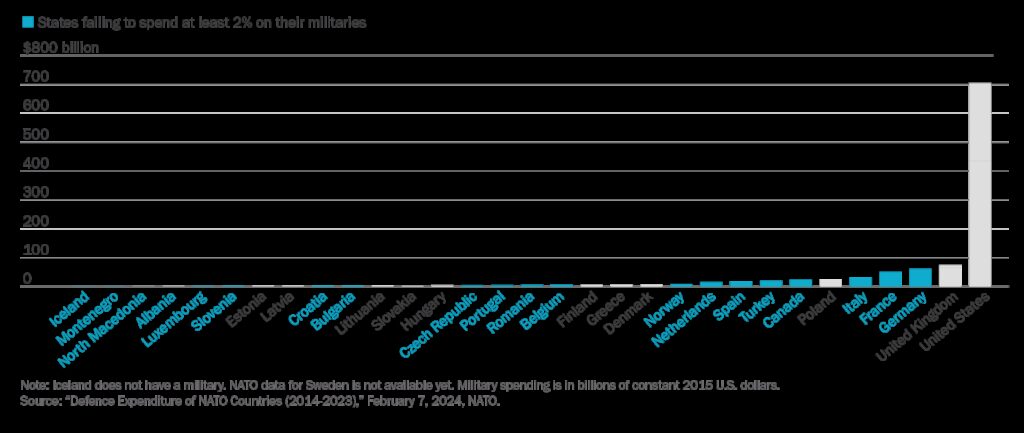

NATO member states’ military spending (2023)

Only 10 European NATO members are spending 2 percent of GDP on defense.

America’s alliances

The United States’ current alliance commitments are largely relics of the Cold War. While the circumstances which produced these commitments have passed, the alliances have not. It thus makes sense to review the historical conditions which produced these alliances in order that the justifications for their continued existence can be scrutinized and appraised.

Changes in U.S. grand strategy over the course of its history produced corresponding changes in its alliance structure. For much of its history, the United States pursued an “isolationist” grand strategy that eschewed “entangling alliances” and sought to stand aloof from European great power politics while consolidating U.S. power in the Western Hemisphere. During the twentieth century, shifts in the global balance of power caused the United States to ally with states in Europe and Asia to prevent the emergence of a rival hegemon in those regions. After the Cold War, however, the United States sought to preserve its primacy by expanding its alliances into a global network of client states and protectorates, leaving it overextended as new great powers emerge in the twenty-first century.

Historical perspective: from isolationism to global primacy

At its founding, the United States was suspicious of enduring alliances and enmities with foreign powers. In fact, the United States breached its very first alliance, signed with France in 1778, by declaring neutrality in 1793 during the War of the First Coalition following the French Revolution, even though French support had been critical during the American Revolution.30 In his “Farewell Address” in 1796, George Washington advised his countrymen “to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world,” and that by “[t]aking care always to keep ourselves by suitable establishments on a respectable defensive posture, we may safely trust to temporary alliances for extraordinary emergencies.”31 In his first inaugural address in 1801, Thomas Jefferson declared the United States’ intention to pursue “peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations, entangling alliances with none.”32 John Quincy Adams declared that the United States “is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all… the champion and vindicator only of her own,” and that

by once enlisting under other banners than her own, were they even the banners of foreign independence, [the United States] would involve herself beyond the power of extrication, in all the wars of interest and intrigue, of individual avarice, envy, and ambition, which assume the colors and usurp the standard of freedom.33

During the nineteenth century, U.S. foreign policy was generally consistent with the dictum to avoid “entangling alliances,” staying out of the affairs of the European great powers while growing and consolidating its power in the Western Hemisphere.34 But in the first half of the twentieth century, the European balance of power became unstable, as Britain declined and first Imperial and then Nazi Germany gained sufficient power to threaten to dominate of all of Europe. Fear that a continental hegemon could cross the oceans and threaten the U.S. homeland drew the United States into European balance-of-power politics.35 As the other great powers allied against Germany found themselves unable to effectively counterbalance it, the United States intervened alongside them to stop Germany from achieving and consolidating regional hegemony.

U.S. nuclear umbrella

The United States is committed to defend 35 countries in Europe and Asia with its nuclear weapons.

Following World War II, the industrialized regions of Western Europe and Japan had been destroyed, and there were only two great powers left in the world: the United States and the Soviet Union. Without other capable states that could balance against the Soviet Union and prevent it from dominating the flanks of Eurasia, the United States felt compelled to deter the Soviets from attempting to conquer a commanding portion of the industrialized world.36 Since the Soviets had a conventional troop advantage in Europe, the United States sought to offset this advantage by threatening to use nuclear weapons if Western Europe or Japan were overrun by a Soviet invasion. This meant bringing the United States’ allies under its “nuclear umbrella,” providing extended nuclear deterrence. Seeking to offset the credibility problems inherent to extended nuclear deterrence, the United States pursued a number of risky strategies, both to gain a nuclear advantage and to demonstrate its resolve37. Fears over credibility were at least partly responsible for drawing the United States into costly peripheral conflicts motivated by domino theories, as in Korea and Vietnam.

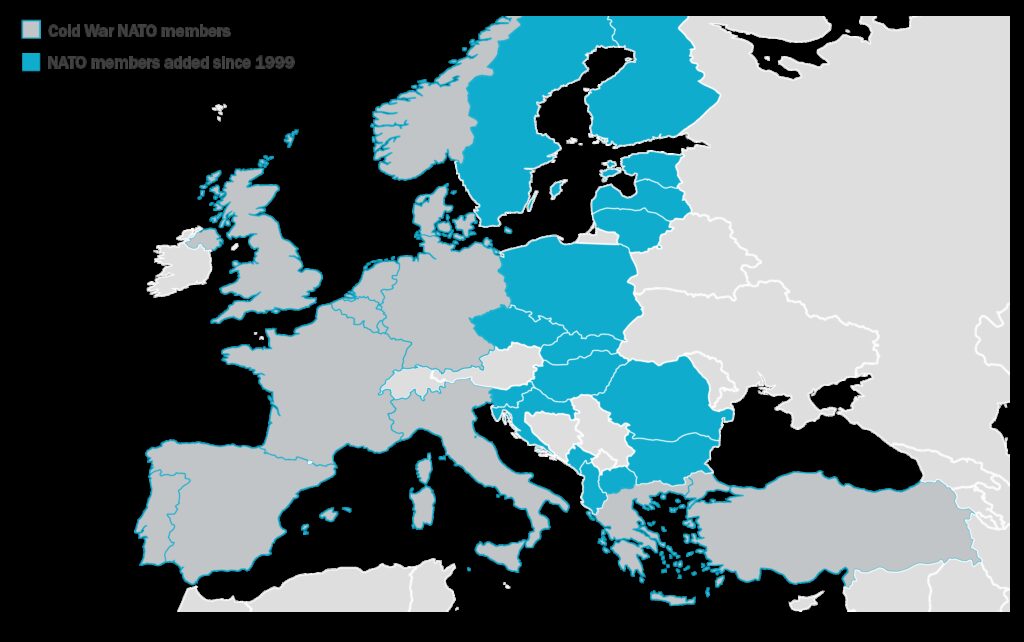

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, America’s Cold War alliances lost their initial reason for being. There was no longer any risk of the Soviet Union conquering Western Europe and becoming a hegemon that could threaten the United States, and the nascent Russian Federation was weak and well-disposed. However, the United States not only maintained its alliances but expanded them considerably. Much of the former Warsaw Pact and a number of former Soviet republics were brought into NATO, while others were promised eventual membership—despite protests from a much-weakened, post-communist Russia.

For many, the “unipolar moment”—during which the United States was the only great power left in the world—should have brought about the end of these alliances, as the threat they were meant to counter had vanished.38 On the other hand, unipolarity also enabled the consolidation and expansion of U.S. commitments to other nations’ defense, as there were few risks posed and no threats to worry about. The United States was making guarantees it never expected to have to uphold, and in exchange, other states felt no need to remilitarize and could instead focus on domestic priorities.

This raises the hypothesis that the forward U.S. presence in Eurasia is not merely intended to balance against aspirant hegemonic powers, but also to suppress the latent power of its own allies, maintaining their status as dependent security consumers rather than independent poles of power in their own right.39

Lord Ismay, the first secretary general of NATO, famously stated that the purpose of the trans-Atlantic alliance was to “keep the Soviet Union out, the Americans in, and the Germans down.”40 Former U.S. national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski articulated a similar view rather more bluntly in 1997 during the heyday of the unipolar moment (emphasis added):

To put it in a terminology that hearkens back to the more brutal age of ancient empires, the three grand imperatives of imperial geostrategy are to prevent collusion and maintain security dependence among the vassals, to keep tributaries pliant and protected, and to keep the barbarians from coming together.41

In 1992, a Defense Planning Guidance draft authored by then-undersecretary of defense for policy Paul Wolfowitz was leaked to the press, which controversially stated that the central aim of post-Cold War U.S. defense policy should be to prevent “the emergence of any potential future global competitor.”42 In regard to the United States’ European allies, the document stated that (emphasis added), “[w]hile the United States supports the goal of European integration, we must seek to prevent the emergence of European-only security arrangements which would undermine NATO, particularly the alliance’s integrated command structure.”43 While the leaked draft was quickly revised for official release, it is hard to review the past three decades of U.S. foreign policy—including the persistent asymmetry within its alliances—and not conclude that the post-Cold War U.S. grand strategy has been to prioritize the expansion and consolidation of the position of primacy the United States had attained following the demise of the Soviet Union.

NATO expansion since 1999

While the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact dissolved in the 1990s, NATO expanded eastward right up to Russia’s borders.

The United States’ attitude towards its alliances in recent decades is therefore about as starkly opposed as possible to the views expressed by the founding fathers. The next sections examine why the United States should revise its alliances to reflect more modest and realistic objectives in line with a new grand strategy of restraint.

Pathologies of the hub-and-spoke model

The United States currently has more than 50 treaty allies spread across seven defense pacts, as well as dozens of other “strategic partners.”44 Most of these alliances have been in effect for about seven decades, despite dramatic changes to the United States’ security environment. Today we see evidence that the U.S. alliance system is experiencing many of the drawbacks to alliances explained in previous sections. That might be acceptable if our alliances were needed to counter a major threat. However, many of our alliances have been inherited from prior eras and circumstances, not intentionally crafted to counter threats in the present.

The first problem with the United States’ alliances is free-riding. Free-riding is often framed in terms of dollar costs, but the more pressing issue is that it results in military unpreparedness on the part of the allies and thus undermines deterrence. The United States has a number of wealthy allies that under-spend on their defense, despite often facing more threatening environments than the United States. In particular, Japan and Germany, the third and fourth largest economies in the world, have consistently spent around 1 percent of their GDPs on defense, despite their respective proximity to China and Russia.45 This problem extends to partners and quasi-allies, like Taiwan, which, despite being in potentially great danger, has been conspicuously casual about its own defense, likely because of its confidence in U.S. protection.46

This is not to say that the dollar costs of U.S. commitments to allies are unsubstantial. Barry Posen, noting the difficulty in specifying the costs of supporting allies—given Pentagon accounting practices and the character of U.S. force structure as a “global strategic reserve”—has nonetheless estimated that $100 billion annually (in 2016 dollars) could be cut from the defense budget “if the United States were more judicious in its promises abroad.”47 Based on cases from 1947 to 2019, Joshua Alley and Matthew Fuhrmann have estimated that on average, the cost of each additional U.S. security commitment is ultimately between $11 billion and $21 billion annually.48 These average expenditures don’t include supplemental aid to partners such as the recent $95 billion package for Ukraine, Israel, and Taiwan, or the previous $113 billion in aid for Ukraine since the beginning of the war in 2022.49

A second problem is reckless driving, whereby allies take risky policy chances they would be too cautious to attempt without the backing of the United States. In addition to being underprepared, the United States’ allies are encouraged by U.S. security guarantees to be less cost- and risk-averse than they would be if they were primarily responsible for their own security. This distorts their decision-making and can lead to provocative behavior vis-à-vis rivals. Japan’s assertive stance on the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands and its provocative dismissal of its neighbors’ grievances from World War II are one example.50 The problem extends beyond the United States’ treaty allies to its “strategic partners” as well. Ukraine targeting early warning radar stations inside Russia, Israeli attacks on Rafah, Lebanon, and Syria, and Taiwan’s claims to “de facto independence” from China are all examples.51

A third major problem is overextension of capabilities and commitments. While U.S. policymakers have historically been paranoid about credibility—arguably fighting unnecessary wars just to prove their willingness to fight over anything—they nonetheless are eager to provide guarantees to states whose security the United States has no vital interest in, and which they cannot confidently defend.52

During the unipolar moment, the United States took on a number of dependents to whose defense it could not be plausibly committed, particularly the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. The dubious credibility of U.S. expanded commitments after the Cold War was in large part compensated for by its overwhelming preponderance of capabilities. With the resurgence of Russia, however, the prospect that deterrence might fail and these commitments may have to be honored has increased, underlining their non-credible and therefore risky nature. The U.S. commitment to use nuclear weapons to defend the Baltics is, on the one hand, implausible enough from the perspective of the security of the United States and the core economies of Europe that Russia might choose to call the United States’ bluff. On the other hand, if Russia were to call the United States’ bluff and attack the Baltics—which would be difficult for NATO to defend conventionally—the United States may, in turn, become more likely to escalate to the use of nuclear weapons if it feels a failure to successfully defend the Baltics would undermine its more important commitments elsewhere.53

Credible deterrence rests on a combination of capability and resolve. It is inherently more credible that a state will defend itself rather than another state. The United States’ “hub-and-spoke” alliance structure—with the United States at the center and its allies maintained as dependents—results in a perverse scenario whereby the states with the most interest in defending themselves neglect their capability to do so, while the state with the most capability has a less obvious interest in taking on the risks of a great power war. This undermines deterrence in these regions by placing all responsibility on the shoulders of a distant and overstretched United States, rather than more proximate and resolute states with considerable latent power potential.

Are the benefits worth the costs?

Advocates of primacy view the United States’ alliances as the architecture underlying the “rules-based liberal international order” and consider them worth any costs the United States has to bear.54 Common arguments are that the U.S. alliance system benefits U.S. security, global stability, trade, diplomatic influence, the bolstering of democracy, and nuclear non-proliferation.55 Were the United States to retrench, so it is claimed, regional security competition would inevitably draw the United States back into military commitments at greater cost, trade would be undermined, nuclear weapons would proliferate, illiberal political forces would spread, and other great powers would expand their spheres of influence.56

Despite the impressive—indeed, seemingly infinite—list of benefits claimed to be attributable to alliances and dangers expected by their attenuation, these claims are all highly dubious.

Alliances can help protect vital U.S. security interests in the face of a major threat, such as a potential Eurasian hegemon, but a threat of such magnitude would require the existence of capable independent allies, not dependents or protectorates. The unrealized power of capable regional actors encourages the United States to directly stabilize these regions, rather than allow them to be stabilized by a local equilibrium of power.

The claim that alliances produce trade and investment benefits to the United States, while commonly assumed, also stands on weak foundations.57 Trade and investment between allies may just as likely be a cause as a consequence of U.S.-backed alliances, and while adversaries indeed appear less likely to trade with one another than allies, it is much harder to demonstrate that formal military allies trade more than states with mere good relations when all other variables determining trade—proximity, size of economy, factor endowments, exchange rates—are held equal.58 Over a number of years, the United States’ top trading partner was also its most likely adversary, China, while its current and long-term top trading partners are its immediate northern and southern neighbors, only one of whom is a treaty ally.59 Similarly, trade among European countries is much more plausibly due to the lower transportation costs provided by proximity and common membership in the European Union, rather than membership in NATO. Nor does U.S. leadership in alliances seem to provide leverage to extract economic concessions from allies, perhaps in part because the United States does little to threaten to leave.60

Nor is there a necessary relationship between U.S. alliances and democracy, unsurprising given that a military alliance is not, contrary to popular opinion, “a community of values.” During the Cold War, the United States supported a number of anti-communist dictatorships. Despite the requirements to gain NATO membership, there is nothing which requires the United States to abrogate its obligations if allies cease to be liberal democracies, and the act of doing so would undermine the supposed strategic rationale for including them in the alliance in the first place. NATO members like Hungary, Turkey, and Poland have undergone lurches towards illiberalism in recent years. Some commentators blame this turn on seemingly omnipresent “Russian influence,” but if NATO is a tool for institutionalizing liberal democracy, why should the very same alliance whose purpose is to deter Russia be failing so badly?61

As the United States’ preponderance of relative power diminishes and the local military balance shifts in favor of powers like China in East Asia and Russia in Eastern Europe, the ability of the U.S. to credibly deter in faraway regions further erodes. This negative tendency is amplified by the sheer number of commitments the United States maintains simultaneously in distant regions of the globe.

Downsizing U.S. foreign commitments

The United States’ alliance commitments are insolvent in part because the United States has committed its overstretched resources either to defend states with the latent capacity to defend themselves or less capable states in whose security it only has a peripheral interest. The United States maintains these commitments out of a fear that extricating itself will produce catastrophic instability. Allies take advantage of this fear by pleading helplessness while deliberately neglecting their own defense.

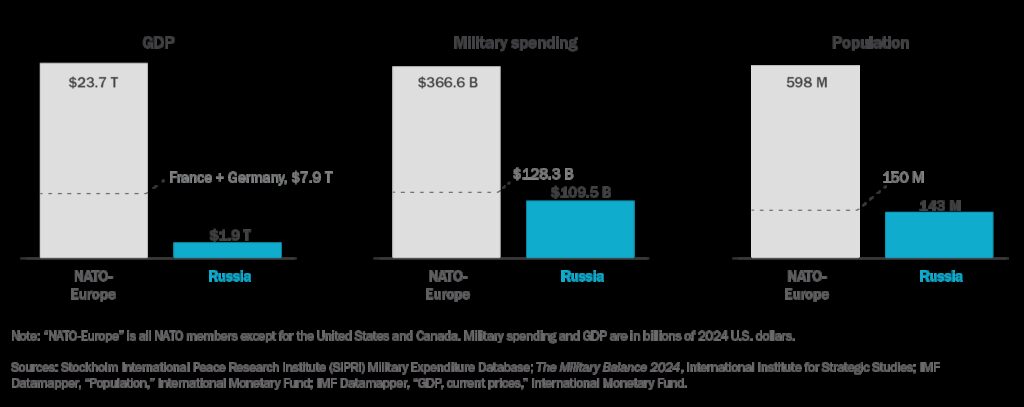

NATO-Europe vs. Russia

NATO-Europe has more than enough latent power to balance Russia and defend itself without U.S. assistance.

But when assessing the international scene, the United States has little reason to be so paralyzed that it can’t prudently adapt to new circumstances. The United States should adopt a buck-passing strategy that incentivizes local powers to balance against threats as they emerge. The United States should act only as the “balancer of last resort” if it deems it necessary to thwart a potential Eurasian hegemon. This means shifting the main burden of defense over to allies and partners, rather than sharing the burden with them.62

NATO’s European nations have more than enough aggregate latent power potential to balance against Russia without the U.S. presence on the continent.63 The European Union has a collective GDP on par with the United States and China. European governments are institutionally sound and have been socialized by decades of cooperation and fraternity. If the United States were to gradually but steadily remove its troops and turn over control of NATO to European commanders, there is little doubt the Europeans would be compelled to take their own defense more seriously. The United States could maintain a separate and limited agreement on security cooperation with the major states of Western Europe and states in the actual North Atlantic. But if it is true, as the Europeans say, that the Baltics, the Balkans, and Ukraine are vital to their security, then it is well past time for them to take on the burden of their defense, rather than the United States shouldering that burden.

In addition to formal ally Turkey, the United States has a number of “strategic partners” in the Middle East, including Saudi Arabia and Israel. The U.S. presence in the Middle East was historically justified by the need to secure a stable flow of oil to the industrial world. That interest has diminished markedly given the diverse and growing number of global energy sources, the ability of other capable states to secure their own interests, and the absence of any single power capable of monopolizing the region’s oil reserves. Moreover, recent Saudi and Israeli behavior indicates that the U.S. commitment to those nations’ defense does not necessarily result in their cooperation on other matters. Evidence of this can be seen in the Saudi refusal to boost oil production following sanctions on Russia, and Israeli settlement-building in the occupied West Bank.64

In Europe and the Middle East, the United States should head for the exits. In the Middle East, this can and should be done more or less immediately, while Europe would benefit from a period of phased but irreversible transition.

East Asia presents a somewhat greater challenge, given China’s more considerable power and the higher threshold needed to balance it. Unfortunately, the local power most likely to lead a regional balancing coalition, Japan, is a habitual “free-rider” on U.S. security guarantees. Japan’s confidence in the U.S. commitment is likely due to the fact that the United States has some 54,000 troops stationed there as a tripwire against an attack.65

If the United States maintains its Asian alliances to hedge against the potential threat of a rising China, it should also make clear to its allies that it is only willing to act as a backstop, not as a vanguard. The surest way for the United States to convey this message would be to remove its forward-deployed troops from East Asia and adopt a maritime strategy, acting as an “offshore balancer.”66 This would not only incentivize regional actors to take principal responsibility for their own defense, but would encourage them to develop security ties independent of the United States, making regional deterrence more credible and durable than if it remained dependent on U.S. guarantees backed by the threat of nuclear use.

U.S. retrenchment may incentivize Japan, Germany, and/or South Korea to seek a nuclear deterrent of their own. While nuclear weapons carry the low-probability and high-consequence risk of nuclear war, they also greatly reduce—even if they do not eliminate—the risk of conventional great power war.67 Conventional wars between great powers were both a recurrent and increasingly costly phenomenon prior to the invention of nuclear weapons, but one has not occurred in the subsequent eight decades that mark the nuclear age. Nuclear weapons discourage conventional war between nuclear powers by raising its costs, compelling caution in the face of uncertainty in order to avoid cataclysmic miscalculation.

The threat by a state like Japan or Germany to use nuclear weapons in order to prevent an existential threat to its survival is infinitely more credible—and therefore produces greater stability—than the current arrangement of extended deterrence. There is no compelling reason to think this would cause a cascade of regional proliferation, as these states’ most likely adversaries—China, Russia, and North Korea—are all already nuclear-armed states, as are a number of their local allies or partners. The threat that nuclear weapons may be acquired by malevolent non-state actors who cannot be deterred is another risk that must be considered, but this is more a question of stability, management, control, and cooperation among nuclear-armed states than one of preventing any and all proliferation among states.68

In 1970, former president Richard Nixon, echoing Lord Palmerston, told Congress that “Our interests must shape our commitments, rather than the other way around.”69 The United States should use this dictum as a guidepost to the formation and dissolution of its alliances, rigorously prioritizing its vital security interests in light of its favorable geostrategic position.

As the world shifts towards multipolarity, the United States should privilege diplomatic agility and prudent hedging over rigid and overbearing commitments of its vast but ultimately finite military power.

Endnotes

1

For a discussion of “the balance of power,” see the second paper in this series, Christopher McCallion, “Grand Strategy: The Balance of Power,” Defense Priorities, April 16, 2024, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/grand-strategy/the-balance-of-power.

2

Viscount Palmerston, “Treaty of Adrianople—Charges Against Viscount Palmerston,” Hansard, UK Parliament, March 1, 1848, https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/1848-03-01/debates/2221a5d7-21f5-49c5-a64a-cc333b61d517/TreatyOfAdrianople—ChargesAgainstViscountPalmerston.

3

Brian D. Blankenship, The Burden-Sharing Dilemma: Coercive Diplomacy in U.S. Alliance Politics (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2023), 8.

4

John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2001), 155–164.

5

There are many gradations of alliances. See U.S. Department of State, “U.S. Collective Defense Arrangements,” January 20, 2017, https://2009-2017.state.gov/s/l/treaty/collectivedefense/; Claudette Roulo, “Alliances vs. Partnership,” U.S. Department of State, March 22, 2019, https://www.defense.gov/News/Feature-Stories/story/Article/1684641/alliances-vs-partnerships/. Also see Chas W. Freeman, Jr., Arts of Power: Statecraft and Diplomacy (Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace Press, 1997), 34–38.

6

Stephen M. Walt, The Origins of Alliances (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987).

7

Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, 1979), 163, 168.

8

John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2001), 155–164.

9

John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2001), 155–164.

10

Thomas J. Christensen and Jack Snyder, “Chain Gangs and Passed Bucks: Predicting Alliance Patterns in Multipolarity,” International Organization, 44, no. 2 (Spring, 1990), 137–168.

11

Mearsheimer, Tragedy of Great Power Politics, 159–162.

12

Waltz, Theory of International Politics, 168.

13

Waltz, Theory of International Politics, 126.

14

For one account of many, see Ludwig Dehio, The Precarious Balance: Four Centuries of the European Power Struggle, trans. Charles Fullman (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1962).

15

George F. Kennan, “Contemporary Problems in Foreign Policy,” speech to the National War College, September 17, 1948, George F. Kennan Papers, Princeton University Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, https://findingaids.princeton.edu/catalog/MC076_c03141; John Lewis Gaddis, Strategies of Containment: A Critical Appraisal of American National Security Policy During the Cold War, rev. and expanded ed. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2005), 24–86; Stephen Van Evera, “Why Europe Matters, Why the Third World Doesn’t: American Grand Strategy After the Cold War,” Journal of Strategic Studies 13, no. 2 (1990): 2–4.

16

Michael Beckley argues that entanglement is rare, see “The Myth of Entangling Alliances: Reassessing the Security Risks of U.S. Defense Pacts,” International Security 39, no. 4 (Spring, 2015): 7–48. Jennifer Lind argues that Beckley defines away meaningful entanglement, covering over its frequent appearance as a justification for war. See Jennifer Lind, “ISSF Article Review 52 on ‘The Myth of Entangling Alliances,’” International Security Studies Forum, April 13, 2016, https://networks.h-net.org/node/28443/discussions/119448/issf-article-review-52-%E2%80%9C-myth-entangling-alliances%E2%80%9D-international.

17

Glenn H. Snyder, “The Security Dilemma in Alliance Politics,” World Politics 36, no. 4 (July 1984): 461–495.

18

Christensen and Snyder, “Chain Gangs and Passed Bucks,” 140–141.

19

Waltz, Theory of International Politics, 167.

20

Michael J. Mazarr, Understanding Deterrence (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018), https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/perspectives/PE200/PE295/RAND_PE295.pdf.

21

Walter Lippmann, U.S. Foreign Policy: Shield of the Republic (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1943), 8–10.

22

See, for example, Thomas C. Schelling, Arms and Influence (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1966), see especially 35–91.

23

Daryl G. Press, Calculating Credibility: How Leaders Assess Military Threats (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005); Jonathan Mercer, Reputation and International Politics (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996).

24

See the essays collected in Dominoes and Bandwagons: Strategic Beliefs and Great Power Competition in the Eurasian Rimland, ed. Robert Jervis and Jack Snyder (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1991).

25

Snyder, “Security Dilemma in Alliance Politics.”

26

An arguable example would be the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Having unsuccessfully tried to enter into a collective security agreement with Britain and France, and having watched them fail to defend Czechoslovakia in 1938, the Soviet Union decided to cut a non-aggression pact with its ideological arch-nemesis, Nazi Germany, temporarily profiting from the mutual carve-up of Eastern Europe. As Randall Schweller notes, however, the argument can be made that the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was an example of buck-passing rather than bandwagoning, as Stalin believed the capitalist powers would fight and weaken each other while the Soviet Union stood aloof as the ultimate beneficiary. See Schweller, “Bandwagoning for Profit,” fn. 43.

27

The Soviets found this out the hard way when Germany invaded in 1941, ultimately killing tens of millions of Soviet citizens. Mancur Olson and Richard Zeckhauser, “An Economic Theory of Alliances,” The Review of Economics and Statistics 48, no. 3 (August 1966): 266–279.

28

Mancur Olson and Richard Zeckhauser, “An Economic Theory of Alliances,” The Review of Economics and Statistics 48, no. 3 (August 1966): 266–279.

29

Barry R. Posen, Restraint: A New Foundation for U.S. Grand Strategy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2014), 44–50.

30

Charles A. Kupchan, Isolationism: A History of America’s Efforts to Shield Itself from the World (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2020), 5.

31

George Washington, “Farewell Address,” September 17, 1796, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/farewell-address.

32

Thomas Jefferson, “Inaugural Address,” March 4, 1801, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/inaugural-address-19.

33

John Quincy Adams, “Speech to the U.S. House of Representatives on Foreign Policy,” July 4, 1821, https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/july-4-1821-speech-us-house-representatives-foreign-policy.

34

See Kupchan, Isolationism.

35

George F. Kennan, American Diplomacy, 1900–1950 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1951), 4–5; Nicholas J. Spykman, America’s Strategy in World Politics: The United States and the Balance of Power (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Company, 1942), 411–457; Hans J. Morgenthau, In Defense of the National Interest: A Critical Examination of American Foreign Policy (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1951), 5–7.

36

Kennan, “Contemporary Problems in Foreign Policy”; Gaddis, Strategies of Containment, 24–86; Van Evera, “Why Europe Matters, Why the Third World Doesn’t,” 2–4. It’s notable that George Kennan, the intellectual architect of American containment policy, was reluctant to continue the deployment of American forces abroad, accepting it only as a temporary stopgap until the economies of Western Europe and Japan could be rebuilt through American initiatives like the Marshall Plan. See Gaddis, Strategies of Containment, 70–75.

37

See, for example, Lawrence Freedman, “The First Two Generations of Nuclear Strategists,” in Makers of Modern Strategy: from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age, ed. Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986), 735–778. Also see Kier A. Lieber and Daryl G. Press, The Myth of the Nuclear Revolution: Power Politics in the Atomic Age (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2020).

38

Christopher Layne, “The Unipolar Illusion: Why New Great Powers Will Rise,” International Security 17, no. 4 (Spring, 1993): 5–51; Kenneth N. Waltz, “The Emerging Structure of International Politics, International Security 18, no. 2 (Fall, 1993): 44–79; John J. Mearsheimer, “Back to the Future: Instability in Europe after the Cold War,” International Security 15, no. 1 (Summer, 1990): 5–56.

39

Brian Blankenship, for instance, has proposed that the United States’ desire for “control” over its allies, or fear of its allies gaining strategic autonomy, imposes the “burden-sharing dilemma” which prevents greater “cost-sharing” within its alliances. Blankenship, The Burden-Sharing Dilemma, 14–15.

40

North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Lord Ismay,” accessed March 15, 2024, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/declassified_137930.htm. Emphasis mine. Zbigniew Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and its Geostrategic Imperatives (New York: Basic Books, 1997), 39.

41

Emphasis mine. Zbigniew Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and its Geostrategic Imperatives (New York: Basic Books, 1997), 39.

42

“Excerpts From Pentagon’s Plan: ‘Prevent the Re-Emergence of a New Rival’,” New York Times, March 8, 1992, https://www.nytimes.com/1992/03/08/world/excerpts-from-pentagon-s-plan-prevent-the-re-emergence-of-a-new-rival.html.

43

Emphasis mine. “Excerpts From Pentagon’s Plan.”

44

See Natalie Armbruster and Benjamin H. Friedman, “Who is an Ally, and Why Does it Matter?” Defense Priorities, October 12, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/who-is-an-ally-and-why-does-it-matter.

45

World Bank, “Military Expenditure (% of GDP) – Japan, Germany,” accessed March 15, 2024, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS?locations=JP-DE.

46

Elbridge Colby, “Taiwan Must Get Serious on Defense,” Taipei Times, May 11, 2024, https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/editorials/archives/2024/05/11/2003817679.

47

Barry R. Posen, “The High Costs and Limited Benefits of America’s Alliances,” National Interest, August 7, 2016, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-skeptics/the-high-costs-limited-benefits-americas-alliances-17273. For a comparison of what $100 billion dollars could buy, see Lindsay Koshgarian, “Seven Things We Could Do if We Cut the Pentagon by $100 Billion,” National Priorities Project, February 21, 2023, https://www.nationalpriorities.org/blog/2023/02/21/seven-things-we-could-do-if-we-cut-pentagon-100-billion/.

48

Joshua Alley and Matthew Fuhrmann, “Budget Breaker? The Financial Cost of U.S. Military Alliances,” Security Studies 30, no. 5 (2021): 680–682. For a debate with Alley and Fuhrmann, see Alexander Cooley, et al., “Estimating Alliances Costs: An Exchange,” Security Studies 31, no. 3 (2022): 510–532.

49

Zolan Kanno-Youngs, “Biden Says Weapons Will Flow to Ukraine Within Hours as He Signs Aid Bill,” New York Times, April 24, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/24/us/politics/biden-ukraine-israel-aid.html; Offices of Inspector General for U.S. Department of Defense, U.S. Department of State, and U.S. Agency for International Development, Joint Oversight of the Ukraine Response, March 27, 2023, https://media.defense.gov/2023/Mar/28/2003187826/-1/-1/1/UKRAINEMAR2023.PDF, 5.

50

Keith Bradsher, Martin Fackler and Andrew Jacobs, “Anti-Japan Protests Erupt in China Over Disputed Island,” New York Times, August 19, 2012, https://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/20/world/asia/japanese-activists-display-flag-on-disputed-island.html; Justin McCurry, “Japan’s Shinzo Abe angers neighbours and U.S. by visiting war dead shrine,” Guardian, December 26, 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/dec/26/japan-shinzo-abe-tension-neighbours-shrine; Keith Johnson, “Why Are Japan and South Korea at Each Other’s’ Throats?,” Foreign Policy, July 15, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/07/15/why-are-japan-and-south-korea-in-a-trade-fight-moon-abe-chips-wwii/.

51

Ellen Nakashima and Isabelle Khurshudyan, “U.S. concerned about Ukraine strikes on Russian nuclear radar stations,” Washington Post, May 29, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2024/05/29/us-ukraine-nuclear-warning-strikes/; Helen Regan, Hamdi Alkhshali and Tamara Qiblawi, “Iran Vows Revenge as it Accuses Israel of Deadly Airstrike on Syria Consulate in Deepening Middle East Crisis,” CNN, April 2, 2024, https://www.cnn.com/2024/04/02/middleeast/iran-response-israel-damascus-consulate-attack-intl-hnk/index.html; Karen DeYoung, John Hudson and Missy Ryan, “Biden administration Straddles its Own ‘Red Line’ on Rafah Invasion,” Washington Post, May 28, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2024/05/23/biden-israel-rafah-invasion/; Courtney Kube, et al., “The U.S. Readies to Evacuate Americans from Lebanon if Fighting Between Israel and Hezbollah Intensifies,” NBC News, June 27, 2024, https://www.nbcnews.com/investigations/us-preps-evacuate-americans-lebanon-fighting-israel-hezbollah-rcna159303; Chris Horton, “Taiwan’s President, Defying Xi Jinping, Calls Unification Offer ‘Impossible’,” New York Times, January 5, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/05/world/asia/taiwan-xi-jinping-tsai-ing-wen.html.

52

Stephen M. Walt, “America Has an Unhealthy Obsession with Credibility,” Foreign Policy, January 29, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/01/29/us-credibility-ukraine-russia-grand-strategy/.

53

War games conducted by RAND in 2014–2015 found the Baltic states would fall to Russia within a few days of an invasion, producing a scenario where NATO would have to fight at great cost and risk to retake them. This has led some to call for a bolstered forward posture to deny Russia the ability to score a quick victory, reflected in recent pledges by NATO to defend “every inch of NATO territory.” This, however, would require the United States to make a substantial additional commitment of its limited resources to countries in which it already has a tenuous interest only to preserve the credibility of the rest of the alliance—a clear case of hazards of entanglement. For an assessment of the war games, see David A. Shlapak and Michael Johnson, “Reinforcing Deterrence on NATO’s Eastern Flank: Wargaming the Defense of the Baltics,” RAND Corporation, January 29, 2016, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1253.html.

54

G. John Ikenberry, Liberal Leviathan: The Origins, Crisis, and Transformation of the American World Order (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011).

55

See, for example, Hal Brands and Peter D. Feaver, “What Are America’s Alliances Good For?” Parameters 47, no. 2 (Summer, 2017): 15–30.

56

See, for example, Thomas Wright, “The Folly of Retrenchment,” Foreign Affairs, February 10, 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/folly-retrenchment.

57

There is a “trade follows the flag” literature which shows a positive relationship between trade and alliances. However, these studies are either limited to the bipolar period of the Cold War or show a significantly weaker relationship under multipolarity. See, for example, Brian M. Pollins, “Does Trade Still Follow the Flag?,” American Political Science Review 83, no. 2 (June, 1989): 465-480; Pollins, “Conflict, Cooperation, and Commerce: The Effect of International Political Interactions on Bilateral Trade Flows,” American Journal of Political Science 33, no. 3 (August, 1989): 737–761; Joanne Gowa and Edward D. Mansfield, “Power Politics and International Trade,” American Political Science Review 87, no. 2 (June, 1993): 408–420. Drezner observes this and challenges the hypothesis that increased trade between allies occurs as a result of favoritism by security dependents for the benefit of their patron, with a particular focus on unipolarity. See Daniel W. Drezner, “Military Primacy Doesn’t Pay (Nearly As Much As You Think),” International Security 38, no. 1 (Summer 2013): 52–79, especially 62–67.

58

Benjamin O. Fordham notes that drawing causal conclusions from these studies encounters endogeneity problems. Fordham, “Trade and Asymmetric Alliances,” Journal of Peace Research 47, no. 6 (November, 2010): 685–696.

59

United States Census Bureau, “Foreign Trade: Top Trading Partners,” accessed August 14, 2024, https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/statistics/highlights/top/index.html; United States Census Bureau, “Top Trading Partners – June 2024,” accessed August 14, 2024, https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/statistics/highlights/topcm.html.

60

Drezner, for example, notes the United States did not gain noticeably better trade terms from its security dependent, South Korea, than the European Union, a friendly non-ally to South Korea did. See Drezner, “Military Primacy Doesn’t Pay,” 62–67.

61

See, for example, Anne Applebaum, “How Vladimir Putin is Waging a War on the West—and Winning,” Spectator, February 21, 2015, https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/how-vladimir-putin-is-waging-war-on-the-west-and-winning/.

62

Christopher Layne, The Peace of Illusions: American Grand Strategy from 1940 to the Present (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2006), 169.

63

Barry R. Posen, “Europe Can Defend Itself,” Survival 62, no. 6 (December, 2020): 7–34.

64

Missy Ryan, “Biden vowed to punish Saudis over oil cut. That’s no longer the plan.” Washington Post, January 26, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2023/01/26/biden-saudis-consequences-oil-cut/; Jillian Ambrose, “Russia and Saudi Arabia to continue oil price pact despite Middle East crisis,” Guardian, October 11, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2023/oct/11/russia-and-saudi-arabia-discuss-effect-on-oil-price-of-hamas-israel-crisis; Matthew Miller, “The United States is Deeply Troubled with Israeli Settlement Announcement,” U.S. Department of State, June 18, 2023, https://www.state.gov/the-united-states-is-deeply-troubled-with-israeli-settlement-announcement/.

65

Mohammed Hussein and Mohammed Haddad, “Infographic: U.S. Military Presence Around the World,” Al-Jazeera, September 10, 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/9/10/infographic-us-military-presence-around-the-world-interactive.

66

Peter Harris, “Moving to an Offshore Balancing Strategy for East Asia,” Defense Priorities, October 31, 2023, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/offshore-balancing-east-asia.

67

Robert Jervis, The Meaning of the Nuclear Revolution: Statecraft and the Prospect of Armageddon (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1989). For a theory of how nuclear powers might still initiate a conventional war despite, or in some ways because of their possession of nuclear weapons, see Glenn H. Snyder, “The Balance of Power and the Balance of Terror,” in The Balance of Power, ed. Paul Seabury (San Francisco, CA: Chandler, 1965), 184–201.

68

Posen, Restraint, 133.

69

Richard M. Nixon, “Report by President Nixon to the Congress,” February 18, 1970, Office of the Historian, Department of State, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v01/d60.