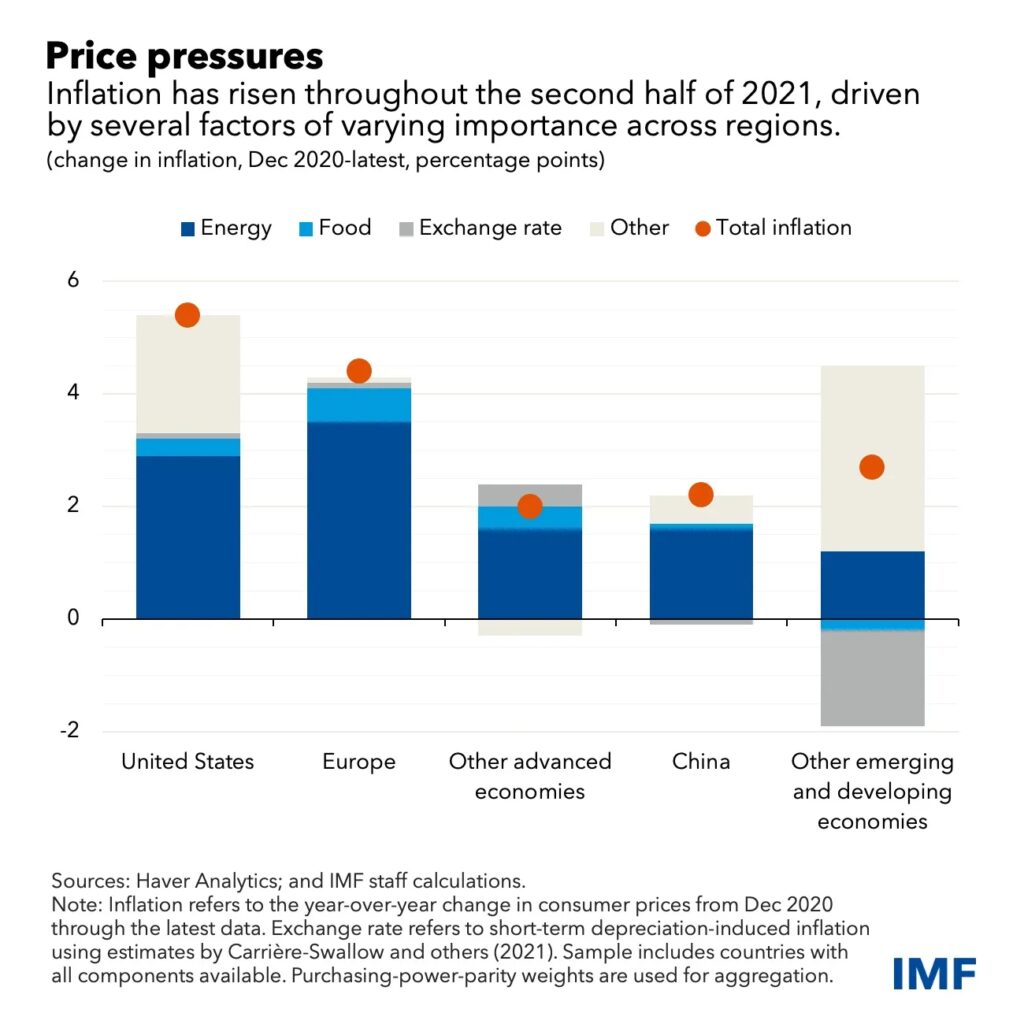

The chart of the week shows how surging energy costs have boosted inflation, especially in Europe, after fossil-fuel prices nearly doubled in the past year. Rising food prices have also helped to boost inflation.

Meanwhile, continuing supply chain disruptions, clogged ports, logistics strains and strong demand for merchandise have broadened these price pressures, especially in the United States. Higher imported goods prices have contributed to inflation in some regions, including Latin America and the Caribbean.

Inflation is likely to remain elevated. Price gains this year will average 3.9 percent in advanced economies and 5.9 percent in emerging market and developing economies, before subsiding next year, according to our January World Economic Outlook update.

Assuming inflation expectations remain well-anchored and the pandemic eventually eases its grip, higher inflation should fade as supply chain woes ease, central banks raise interest rates, and demand tilts more toward services again instead of goods-intensive consumption.

Oil futures contracts indicate crude prices will rise about 12 percent this year as natural gas prices climb about 58 percent. Such increases for both commodities would be considerably less than their gains last year, and would likely be followed by falling prices in 2023 as supply-demand imbalances ease further.

Similarly, food prices are likely to climb at a more moderate pace of about 4.5 percent this year and decline next year—after a rise of 23.1 percent last year, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. This should ease spending pressures for millions of people around the world, especially in countries with lower incomes.

Such burdens fall most heavily on residents of emerging and low-income nations, where food typically makes up a third to half of consumer spending. That share is smaller in advanced economies, such as the United States, where food accounts for less than one-seventh of household shopping bills.