Space stations are the harbinger of a deepening bipolarity in the international relations of space. The United States leads the International Space Station (ISS), and will lead whatever comes after it, but it is no longer seen as the uncontested unipolar power in space. China now also has a national space station, named Tiangong, which represents a momentous achievement for the country’s space program.

The ISS and Tiangong are not divorced from the quest for national technological supremacy. If technology is ‘power in practice’ for China, it is no less important for the United States, which has long seen the transformative potential of technology as critical to its national security.

The United States has also shifted to a more muscular industrial policy in an attempt to lead in the industries of the future. In a bid to sustain its pre-eminence, it has put technological decoupling into motion in such a forthright way that there is little doubt that it seeks to block China from becoming a technological peer of any kind.

Great power competition over technology is now out in the open. This extends to matters in space for both countries and is unlikely to go away anytime soon.

From a US perspective, it is cause for concern that China was the first to land on the far side of the moon, aims for the same lunar resources in the race back to the moon, can carry out complex sample-return missions, has plans for a permanent moon base and now also has a space station that is seen as second only to NASA’s in technological sophistication.

Concerns about technological primacy in space are also intertwined with concerns about other threats that space stations face — or pose.

The life of any physical infrastructure can only extend so far. The ISS is currently projected to survive to 2030, while Tiangong is expected to remain operational for about 10 years. But collisions with debris and other objects are a common threat. The ISS can dodge speeding debris, but sometimes gets hit. Mega-constellations of satellites are also a challenge for space stations. Starlink satellites have already been confirmed to have had close encounters with China’s space station and it, too, has engaged in collision avoidance.

Then there are the disturbing ‘uncontrolled’ threats. As the viability of China’s space stations has grown, so too has the finger pointing about uncontrolled entries and failures to engage in responsible behaviour. China has drawn flak for the uncontrolled re-entries of parts of its Long March 5B rocket that delivered modules to Tiangong. The debris has scattered all over the world — in the Ivory Coast in 2020, in the Indian Ocean in 2021, and near the Philippines’ Palawan Island and in the Pacific Ocean in 2022. The uncontrolled entry of its experimental space lab in 2018 was also a cause for global apprehension.

In China, one view is that these criticisms are simply attempts to discredit or sabotage progress on its space station. After all, the ISS has itself gotten out of control, leaving everyone from the ground to the ISS scrambling to regain stability of the sprawling station. In 2021, a software glitch caused the ISS to pitch out of its normal flight position, and both attitude control over the station and communication with its seven-member crew were lost.

These threats are common to all space stations and when wrapped up in geopolitics they can be useful for bringing allies on board. While it is not clear whether allies will stay glued to one side or the other, it is evident that alliance politics is extending to space more than ever before. This is why China may well work towards cultivating a reputation for more responsible stewardship of space.

The United States cocooned the ISS in an alliance architecture, drawing together even former adversaries. Led by NASA, a 1998 agreement between five space agencies — belonging to the United States, Canada, Japan, Europe and Russia — has governed collaboration on the ISS.

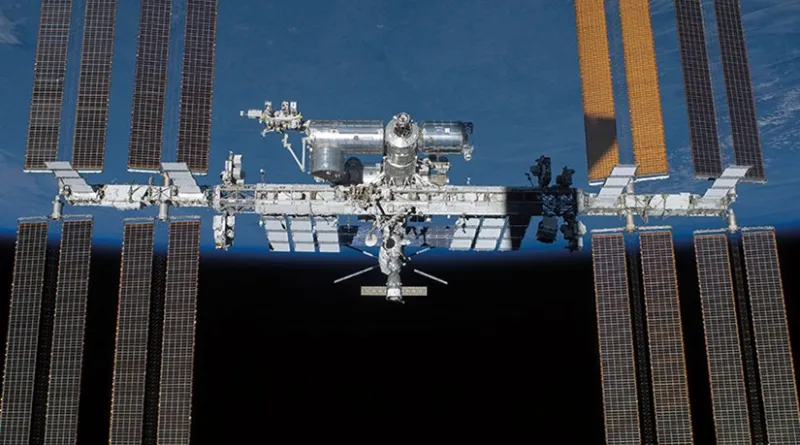

The ISS is heavily promoted as an inspiring scientific achievement. Over 260 individuals from 20 countries have visited the largest collaborative infrastructure ever built in space to date, and thousands of researchers from across the world have used its facilities to carry out experiments.

But the ISS is only scientific and international up to a point. Canada, Japan and Europe are also core US military allies, a fact that is proving useful to the United States in the new lunar space race. And China has not been able to gain entry.

China is itself on a quest for space allies and partners. Through Tiangong, it strives to showcase scientific and technological experiments and exchanges. As with the ISS, China parades its space station’s range of partners — including the European Space Agency, France, Germany, Italy, Russia, Pakistan, Kenya and the UN Office for Outer Space Affairs. Tiangong is hailed as the ‘first of its kind open to all UN member states’.

If things stay their course, China may well be the only country with a functioning national space station. This is because, aside from opening the ISS for commercial and marketing opportunities, the post-ISS future is a work in progress for the United States. The US is tied to the dream of commercial space stations, but whether this space dream comes to fruition remains to be seen.

Meanwhile, it is foreseeable that there might be a gap in US presence in space, one that China is aiming to fill.