At the beginning of the Syrian conflict in 2011, the Iranian government announced it would provide strategic support to the Bashar al-Assad regime without direct military intervention. However, as the conflict wore on and opposition forces began to wrest control of areas from the regime, Iran directly intervened in various Syrian fronts to prevent the fall of Assad, particularly between 2013 and 2018.

Since the beginning of 2018, Iran has been directly involved in the battle against the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) in eastern Syria. Through its participation, Iran has been able to carry out its expansion project on the eastern fronts of Syria, specifically in Deir ez-Zor, a province bordering Iraq that is troubled by a fragile security situation.

Iran’s participation in anti-ISIS battles has helped it shore up military authority in several key areas. First, in the city of al-Bukamal along the Syria-Iraq border, which links Iran to the Mediterranean Sea through Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon—countries Iran has already secured land routes. Second, on the main roads that connect Deir ez-Zor province with the provinces of Homs and Raqqa. Third, in the most important cities and towns in the province, including in Deir ez-Zor, albeit cautiously due to Russian presence there since 2018. This complex calculation will be discussed later in the factbox.

Perhaps the most prominent goal Iran has achieved in Deir ez-Zor is its control over al-Bukamal and its border crossing with Iraq, which enabled Iran to achieve a dream held since the founding of the Islamic Republic in 1979: to open a land corridor from the Mediterranean Sea and Lebanon through Syria and Iraq. For years, this remained one of the most paramount regional concerns, as Arab countries and Israel fear Iran will tighten its control over the land routes stretching from Iraq to the Mediterranean and therefore control an important land transportation node. The international community is also wary of Iran’s influence in al-Bukamal, fearing it could become a bridge to the country.

After focusing on expanding its security and military influence across Deir ez-Zor province, Iran began thinking of consolidating power beyond those spheres, aiming to extricate the exhausted community from the control of ISIS and the war that destroyed most of the province’s economy, infrastructure, and social institutions.

Iran tried to achieve this new kind of influence by providing—often inadequate—services to the community, a tactic Iran previously pursued in Syria, focusing on quantity rather than quality, especially in the service field and economic investments.

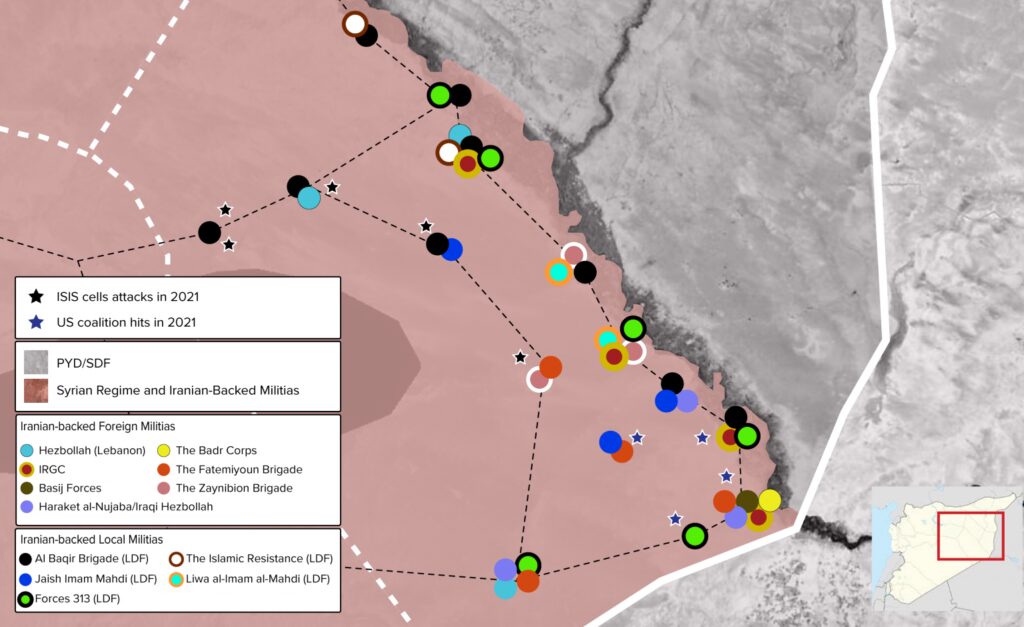

In early June 2018, Iran’s local and foreign militias, with the participation of Syrian regime forces, managed to take control of al-Bukamal and its border crossing after months of battles, in which Iran initiated attacks from three main areas:

The T2 station—located in the southern desert outside the city—under the commandership of Lebanese militant group Hezbollah and regime forces.

Inside Iraqi territories bordering al-Bukamal, through the Popular Mobilization Forces and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

The Al-Mayadin-Al-Bukamal highway, led by Iran-backed Pakistani and Afghan Shia militias and the Syrian Local Defense Forces—the latter of which was made up of local fighters recruited by the IRGC.The period following the battle of al-Bukamal was marked by Iran’s desire to solidify its military and security control over its areas of influence. Iran did not want to not repeat the mistakes made in Aleppo city, where continued disagreement between its foreign and local militias undermined the IRGC’s authority. Iran seeks to distribute tasks among its militias on the ground to ensure the preservation of gains and the persistence of Iranian influence. The following is a breakdown of Iran’s militias in the governorate of Deir ez-Zor:

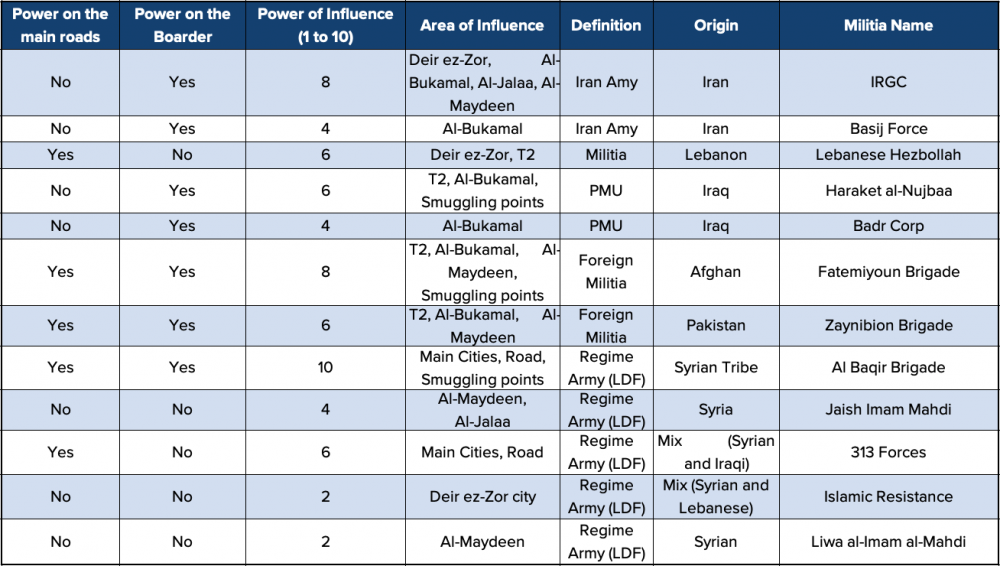

IRGC: Thousands of fighters and military advisors are deployed in Syria, but Tehran only acknowledges advisors who assist government forces.

Iraqi Shia militias: Iraqi groups are fighting alongside Syrian regime forces per Iran’s request. They have been deployed mainly on the border strip between Iraq and Syria since the end of the operations against ISIS in 2018-2019. Additionally, some Iraqi militias are present in al-Bukamal. Among the most prominent of these groups are Kataib Hezbollah, Badr Brigades, and Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba.

Lebanese Hezbollah: Considered the most powerful Iran-backed military force in wider Syria, Hezbollah’s weight in Deir ez-Zor is no exception. The militant group has been openly participating in the fighting alongside regime forces since 2013. The number of Hezbollah forces has decreased during the past two years as the intensity of the battles declined and regime forces regained control of about two-thirds of the country. In Deir ez-Zor, Hezbollah began focusing on recruiting and providing military training and assistance to local forces collectively known as the “Islamic Resistance.”

The Afghan Fatemiyoun Brigade and Pakistani Zainabiyoun Brigade: The IRGC established the two brigades with Afghan and Pakistani Shia fighters. They participated in several key battles in Syria and maintain a significant presence in Deir ez-Zor today—about 2,500 fighters total—and in other areas throughout the country.

Local Defense Forces: Iran recruited fighters from Aleppo, Deir ez-Zor, and Raqqa provinces under the name of the Local Defense Forces (LDF). The LDF is considered part of the Syrian army and has over fifty thousand fighters. The most prominent LDF militias operating in Deir ez-Zor are: al-Baqir Brigade, 313 Forces, Islamic Resistance, Jaish al-Mahdi, and Liwa al-Imam al-Mahdi.A struggle for control and influence between Iran and Russia

At times throughout the Syrian conflict, the interests of Russia and Iran have been aligned on more than one front, as both countries aim to protect Assad’s regime and erode the power of the Syrian opposition and ISIS. However, in recent years, their interests have begun to diverge and a competition between the two countries—while not fully on the surface—is now heating up.

Over the past several years, Russia has repeated the same mistakes in dealing with Iranian military deployment in Syria. Russia has allowed Iran-backed militias to move freely, filling gaps created by several agreements that Russia struck with the Syrian opposition, which had prompted the rebels to leave the area.

– The type and level of relationship with the Iranian leadership (3 points)

– Approximate number of fighters and weapon type (2 points)

– Extension of control over international roads (2 points)

– Extension of control over Iraqi borders (2 points)

– The type and level of relationship with local actors (1 point)

Russia failed to avoid this mistake in Deir ez-Zor, which allowed the IRGC to expand its power in the province. However, in 2020, Russia began attempts to impose military might in Deir ez-Zor—even if only in a limited capacity—because of its desire to keep some form of control to monitor Iranian expansion in this area and to eliminate ISIS cells. The change in Russia’s strategy began to take shape in December 2020, witnessing the deployment of Russian forces and members of the Russian-backed Fifth Corps in several cities in the eastern countryside of Deir ez-Zor. The arrival of Russian forces to the areas bordering Iraq was the first of its kind in years and poses a direct threat to Iran’s most prominent stronghold in eastern Syria.

Russia’s new military deployment in Deir ez-Zor was met with resentment among the local leaders of Iran-backed militias. Those leaders have a strong base in society, which prompted Russia to reach an agreement with Iran that limits the areas of deployment of Russian forces.

Moscow confirmed the motivation behind its recent actions in Deir ez-Zor: to fight ISIS sleeper cells, not to limit or control Iranian influence in the region. Tehran didn’t oppose the Russian moves; in fact, the IRGC even gave the Russians logistical support. In return, Iran hopes the new Russian deployment will help limit the missile attacks carried out by US drones against Iranian areas of influence in the Deir ez-Zor region. The following are the most prominent points included in the agreement between Russia and Iran:

The withdrawal of Harakat al-Nujaba as well as Lebanese and Iraqi Hezbollah from their biggest base in the village of al-Heri. They are to be replaced by the Fifth Corps and Russian military police in order to carry out periodic patrols.

The Iran-backed militias that control al-Bukamal allowed and even assisted the Russian military police in establishing several checkpoints at the city’s western entrance. Later on, the presence decreased as the Russian military police withdrew in March 2021 from their point in al-Bukamal to the city of al-Maydeen for unknown reasons.

Direct military support by Iran-backed militias to the Fifth Corps against ISIS sleeper cells in Deir ez-Zor. However, this arrangement lasted for less than a month, as these militias suffered significant losses and the Russians refused to allow them to head the operation.At the beginning of 2021, Iran’s aspirations to use the Russian presence near its areas of influence as a shield to deter any attacks by the US-led coalition failed miserably, with early 2021 witnessing the heaviest strikes on Iran’s sites in Deir ez-Zor. This opening salvo clarified the nature of the new US administration’s policy toward Iran’s presence in Syria, specifically in Deir ez-Zor.

Since the US airstrike in eastern Syria on February 25, Iran has realized it must change its policy toward Russian deployment, as Russia’s presence has shifted from being a mutual interest to a direct threat and has not protected Iran-backed militias from US drones attacks. Perhaps the most notable change in how Iran deals with the Russians was the reduction of military support from its militias to the forces of the Fifth Corps and the Palestinian al-Quds Brigade in their battles against ISIS. This was a main cause for the increase in ISIS attacks on the regime forces in the first quarter of 2021. This also led to a significant increase in casualties among the Fifth Corps and the Palestinian al-Quds Brigade.

Due to the lack of international interest in the regime-held areas in Deir ez-Zor and the lack of international monitoring of the IRGC’s plans in that region, Iran has been able to build a military and a security empire in eastern Syria. Nevertheless, the question remains: to what extent will Iran be able to maintain its military influence in Deir ez-Zor if Russia becomes less tolerant of Iran’s meddling?