Canadian company Tajiri Resources announced on August 20 that it had entered into an agreement with Sahara Natural Resources to begin drilling in Burkina Faso at the company’s exploration program on the Reo Gold project, located 130 kilometres west of the capital, Ouagadougou.

The initiation of a mining project, even during the COVID-19 pandemic, reflects the entrenchment of extractive imperialism, and its determination to continue exploiting the country’s workers, regardless. For example, West African gold mining company Roxgold continues to operate its Yaramoko Mine Complex, despite confirming two positive cases of COVID-19 at the site.

Industrial mining in Burkina Faso has only evolved during the past decade, with industrial gold production rising tenfold, from five tons in 2008 to more than 50 tons in 2018.

The country — which is referred to as a Gold-Endowed, African Low-Income Country (GALIC) — has 154 metric tons of gold reserves and has mainly attracted substantial investment in gold mining. During 2007–14, Burkina Faso experienced a gold rush and jumped from sixteenth- to fourth-largest gold producer on the African continent.

In 2012, an incredible 941 mining permits and licences were issued.

From 2007–10, seven gold mining companies came into operation and gold production multiplied eight-fold. In 2010, the revenue from gold exploitation represented 63.8% of total export revenues and 7.7% of GDP. Furthermore, in 2012, earnings from the exploitation of gold rose substantially from CFA440 billion to CFA806 billion.

Mining and underdevelopment

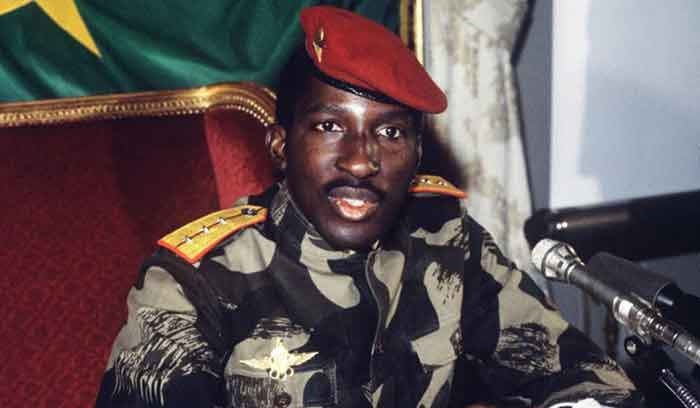

The advent of extractivism in Burkina Faso has brought little benefit to the country’s oppressed people. The Comptoir Burkinabe des Métaux Précieux (Berkinabe Precious Metals Counter) was established by Thomas Sankara’s revolutionary government in 1986, to install state monopoly on the production, transformation, export and purchase of gold. Through state regulation, the entry of private capital was greatly hindered. With the assassination of Sankara in 1987, neoliberal mining laws were instituted by the new administration, aimed at fostering the entry of foreign and private capital. This was achieved by the squeezing out of non-industrial mines and aggressive elevation of industrial exploitation financed by multinationals.

With the help of the new laws, six western mining companies started operating and all of them expatriated their profits, thereby contributing to the super-exploitation and consequent underdevelopment of Burkina Faso.

The extent of super-exploitation is indicated by the share of government income from the seven largest gold mines — only 10%. Moreover, mining areas rank among the poorest in the country and the cost of living in these mining locations is significantly higher than in other rural areas.

While talking about people displaced by extractivist operations, one NGO stated: “Their fields have been taken away. Now they have neither fields for farming activities nor jobs in the mine.

“For the local population, the mines do not have any benefit at all”.

The displacement of people due to industrial mining is expected, since it requires large amounts of land. At the local level, the land required for mining may be substantial and may result in competition with other land uses.

In Burkina Faso, subsistence agriculture based on cereal growing (sorghum, millet, maize and rice) is the predominant regional activity, employing 80% of the population. Correspondingly, farming is the most affected by mining activities, reducing food production and increasing food insecurity.

Elaborating on the deleterious impacts of mining, a report by the organisation Global Change — Local Conflicts presents an alternative analysis of extractive imperialism in the country.

Mining greatly accelerated in 2018 when exploration and exploitation permits for industrial mining were issued for almost half of the surface of the country. With this acceleration, the suffering of Burkinabes concomitantly increased.

While talking about the Perkoa zinc mine — owned by Australian company Blackthorn Resources Limited — a resident said: “This mine has made us very poor in this village.

“The area of the mine was the granary of the village and above all the basket of the housekeeper. We no longer have access to all that nature had given us.”

Similarly, a peasant from the same area stated: “The mine has sabotaged us; it promised not to tramp on our backs and today it tramples on our heads.

“The mine lacks respect for our village, when arresting and imprisoning our youth.”

A history of resistance

Neo-colonial mining has resulted in significant conflicts, as extractive corporations have found it difficult to impose underdevelopment on the people of Burkina Faso.

Freelance researcher Lila Chouli’s booklet outlines the coercive contours of extractivism in Burkina Faso.

At the Tarpako mine, operated by Canadian company High River Gold, the establishment of extractivism meant the expropriation of peasant land; destruction of traditional gold mining, the main activity of the villagers; the emergence of a water crisis; rise in the cost of living; and intense monitoring by private security guards.

Similarly, when the Kalsaka mine was established, the mining company imposed its monopoly by banning artisanal mining. In response, the traditional gold miners, deprived of their livelihood, organised themselves in an association called Nabons-Wende to defend their interests.

This was the result of the income destruction of nearly 3000 people in the area of Kalsaka, who suddenly found themselves with no existential security.

At the open-pit gold mine Essakane, located in the province of Oudalan in the north-east and owned by Canadian firm International African Mining Gold Corporation, a strike was organised by the trade union Syndicat National des Travailleurs des Mines et Carrières du Burkina from December 13–16, 2011.

The courageously protesters said: “While the ministers in charge of the mines are happy to dine with the mining bosses, they never have as much as 30 minutes to talk to the local people.

“So let the riot police come. Some of us will fall. We want to see the police shoot at us. But we also have confidence in ourselves. We are sure we will eventually overcome Essakane mine.”

Between May 2011 and December 2014, strikes also occurred against the deregulation of working hours at the Belahouro mine, run by British group Avocet Mining PLC and located about 220 kilometres north of Ouagadougou.

In the Bissa Gold mine, run by the Amsterdam-based company Nordgold at Kongoussi, 85 kilometres north of Ouagadougou, there was a powerful strike on November 1, 2014, in which 90% of the workforce participated.

The strikers demanded “wage increases, long-term contracts, the conclusion of labour contracts directly with the operating company Bissa Gold and not with intermediate personnel firms, changes in the working schedule (from a fourteen-day cycle of working days and days off to a seven-day cycle) and the admission of trade union committees.”

In 2006, the government granted a mining concession to SOMIKA, a Burkinabe company, in Yagha Province in the north-east. Residents soon complained that SOMIKA not only banned artisanal mining within, but also beyond the concession area.

In response, the company hired security guards who forcefully seized the artisanal miners’ extracted stone; physically assaulted people to check if they were carrying gold; and intimidated the artisanal miners to sell the gold they had extracted to SOMIKA below the market price.

These tensions culminated eight years later, in a protest organised by village residents and artisanal miners on October 30, 2014. The national police and SOMIKA’s security guards shot at the demonstrators. Four young demonstrators died on the spot and a fifth on the way to the hospital.

In 2013, Canadian company True Gold received a concession for an area comprising 28 villages, where artisanal mining represented an important source of income for the local population. The granting of concession was antithetical to the sentiments of the residents who, at a public consultation held as part of the environmental and social impact assessments, argued that the mine would impact health and environment; result in the loss of land for subsistence farming and as well as the loss of places and animals with cultural and spiritual significance.

Despite these explicit objections to the mine, the Burkinabe state chose to bend to the demands of Canadian extractivism.

The way forward

While extractive imperialism is negatively impacting Burkina Faso, artisanal mining also has its drawbacks.

Due to artisanal mining, children as young as six have been abandoning school to work mainly in mines where they crush stones, sieve dust, transport water and cook. In 2014, the net primary school enrollment rate for the entire nation was estimated at 64.4% for children aged 6 to 11 years of age and only 42.2% for the Sahel region, where gold mining is prevalent.

Furthermore, mining companies and artisanal miners use water resources unsustainably for the production of gold. The use of motorised pumps for transporting water to areas lacking streams, and the lowering of the groundwater table in the pits to allow access to gold-containing minerals, are some of the ecologically harmful aspects of gold mining in Burkina Faso. By using pumps, water is discharged with a high sediment content, which can reduce the quality of rivers and result in land degradation.

To build an alternative to contemporary mining practices, an eco-socialist approach needs to be adopted, whereby strong environmental controls can be implemented and ecological damage prevented. On top of this, an eco-socialist economy would also reconstitute the transnational regime of capital accumulation.

Currently, international corporate investors account for nearly 90% of Africa’s gold production. In place of corporatocracies, an eco-socialist approach would support the democratic ownership of resources and the elimination of the profit-maximising objective. It would also minimise the need for mining, by putting an end to the egregious waste of resources under capitalism, driven by obsessive consumption and the large-scale production of useless commodities.

Sankara articulated this point succinctly, when he told the first International SILVA Conference for the Protection of the Trees and Forests in Paris: “We are not against progress, but we do not want progress that is anarchic and criminally neglects the rights of others.”

In Burkina Faso, an eco-socialist struggle needs to be waged against the “anarchic” growth of capitalism that is decimating the entire country in pursuit of profit.