As a terrorist attack was unfolding late Monday night in Vienna, where four people were killed and 22 others injured in a shooting rampage on crowded bars, speculation about the culprit, unsurprisingly, was rife on social media. Many of those offering theories were quick to accuse Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of stoking the rage of militant Islamists.

There is no indication that the attacker—a young extremist who it turned out had previously been convicted in Austria for trying to join the Islamic State—was motivated by Erdogan, as Austrian authorities have pointed to his ISIS sympathies and the Islamic State’s subsequent claims of responsibility for the attack. But the immediate suspicions that Turkey’s leader was indirectly responsible reflect anger in Europe at Erdogan’s response to recent jihadist attacks on the continent.

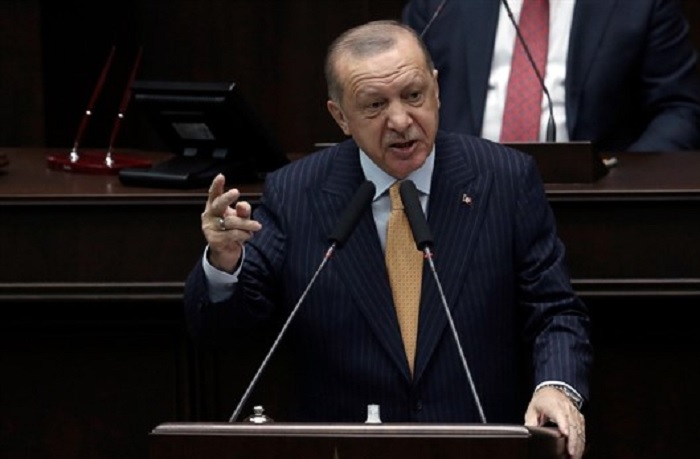

Erdogan, in keeping with a well-worn pattern, has deliberately made himself a lightning rod, trying to benefit from the tensions within Europe over Islam by claiming he is the defender of all Muslims. In doing so, he is inflaming Turkey’s already fraught relations with its fellow NATO members and adding to his unpopularity among many Europeans. Erdogan is also paradoxically making the position of Turkish immigrants living in countries like Austria, Germany, the Netherlands and elsewhere in Europe more difficult, as they are increasingly seen there as potential weapons for Erdogan in his political battle against the West. Erdogan has already tried to do this elsewhere in Europe. As I pointed out in a column in 2017, Erdogan inserted himself into parliamentary elections in the Netherlands that year, sending his foreign minister to hold a campaign rally against the wishes of the Dutch government and openly seeking to influence voters of Turkish descent.

But the epicenter of these tensions lies in the relationship between Erdogan and French President Emmanuel Macron, who has responded forcefully—some argue too forcefully—to recent terrorist attacks in France. Bilateral relations between Turkey and France, already on shaky ground before, are now at the breaking point.

On Oct. 16, a Muslim refugee of Chechen descent killed and beheaded a teacher, Samuel Paty, in a Paris suburb. During a class about freedom of expression, Paty had showed his students some of the controversial cartoons by the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, depicting the Prophet Mohammed. The cartoons, of course, were cited as the motivation behind one of the most traumatic days in France, in 2015, when jihadists massacred the staff at Charlie Hebdo’s office in Paris and killed others, including patrons at a Jewish deli. Paty’s brutal murder struck the French particularly hard, because he died for his defense of free speech, a near-sacred principle in France’s devotion to laicite, or secularism.

Macron immediately launched a crackdown, shutting down Islamist organizations across France and declaring that his government would “intensify its fight against radical Islamism.” He put the struggle in stark terms by saying that authorities would take measures against individuals and groups promoting “a radical Islamist project—in other words, an ideology aimed at destroying the French Republic.”

Erdogan soon went on the offensive, harshly criticizing Macron. When another attacker killed three people at a church in Nice on Oct. 29, slitting the throat of one woman, Erdogan remained undeterred. “Macron needs some sort of mental treatment,” Erdogan declared at a party meeting. “What else is there to say about a head of state who doesn’t believe in freedom of religion?” France called the statements “unacceptable,” and recalled its ambassador from Ankara.

Erdogan has deliberately made himself a lightning rod, trying to benefit from the tensions within Europe over Islam by claiming he is the defender of all Muslims.Then Erdogan upped the ante. In a televised speech to the nation, two days later, he called for a boycott of French products, and absurdly claimed that French Muslims are “subjected to a lynch campaign similar to that against Jews in Europe before World War II.” He urged the rest of the world to stand up for Muslims in France. European leaders promptly expressed their support for Macron. But Erdogan’s criticism of Macron’s response has been echoed by populist leaders in Pakistan and Malaysia, and by protesters in the Middle East and across the Muslim world.

To many Europeans, Erdogan’s words have sounded like veiled justification for the killings and incitement to more violence. Philosophically, this is a clash over the limits of free speech and the French government’s appropriate response to terrorism. But the dispute is unfolding in a context of geopolitical competition, with Erdogan staking out one side and Macron the other.

Some of Macron’s critics claim he is playing domestic politics, guarding against rightist rivals with his vows to crack down on Islamist extremists and defend the right to offend. But Macron’s response has also echoed popular sentiment in France. When some liberal observers in the U.S. accused Macron of trying to gain a political advantage with his tough stance, many in France said Americans just don’t understand. Even Le Monde, a leftist newspaper, complained of a “disconcerting American blindness regarding jihadism in France.”

Whatever Macron’s motivation, Erdogan’s is clear. He is playing a familiar game—the same one he has played for years, trying to crown himself leader of the modern Muslim world. He did it in 2009, when he theatrically stormed out of a panel at the World Economic Forum in Davos, after attacking Israel’s president, Shimon Peres, over the situation in Gaza. And he did it during the height of the Arab Spring nearly a decade ago, when Muslim Brotherhood-linked parties were winning elections in Tunisia and gaining influence in Egypt and Libya. Erdogan traveled to all three countries in an apparent victory lap, projecting himself as the leader of what briefly seemed like nascent Arab democracies dominated by Islamist parties.

That project collapsed, but Erdogan has not given up his aspirations to extend his influence beyond Turkey’s borders, even as domestic economic problems mount. In addition to Erdogan’s aggressive moves toward Macron, friction was already spiking over a number of other issues, most notably Erdogan’s push to send Turkish vessels in search of oil and gas fields in the contested waters of the Eastern Mediterranean, a dispute that produced some close calls this past summer when it looked like it might lead to a military conflict. Turkey’s military involvement in Libya is another source of friction, as is Ankara’s support for Azerbaijan in its conflict with Armenia over the disputed enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh.

It is quite possible that the Vienna attack would have occurred without any words from Erdogan or Macron. But with Europe in the midst of what could become another wave of terrorism, patience with Erdogan’s rhetoric is wearing thin.