The police takedown of encrypted communications provider Sky ECC has led to a spate of new arrests across the Balkans, notably that of notorious drug boss Darko Saric and the former head of Montenegro’s top court. Whether justice will come is still in doubt.

They arrived in force at around 10 a.m., about a dozen black police jeeps lined up on a sloping street in the affluent Belgrade suburb of Dedinje, home to foreign ambassadors, the mausoleum of Josip Broz Tito and, since his release from prison in December, a notorious drug boss called Darko Saric.

Saric had been behind bars since 2014 when he was arrested on suspicion of smuggling 5.7 tonnes of cocaine from South America to Europe. In 2018, he was convicted and sentenced to 15 years. Then in 2021, the verdict was overturned and a retrial was ordered. Saric was released at the end of last year but placed under house arrest pending his retrial.

The police spent eight hours inside his wife’s home, an imposing yellowish building surrounded by a high white fence with security cameras on the corners. By the end of the day, April 14, Saric was back in custody on suspicion he continued pulling the strings of his cocaine-smuggling empire from behind bars and ordered the murder of long-time partner and fugitive Milan Milovac.

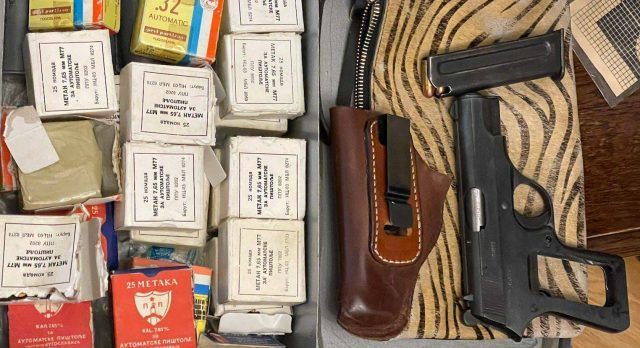

How? Reportedly with the use of several mobile phones, two satellite phones and a custom device installed with a subscription-only, encrypted messaging system called Sky ECC.

When a French and Dutch-led police operation cracked the code to Sky ECC in February 2021, investigators gained access to a treasure trove of real-time evidence against a host of international crime gangs.

Thousands of people have been arrested around the world based on the Sky ECC takedown; in the Balkans, Saric is the biggest, but he is far from alone.

In Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Albania, Montenegro and Slovenia, almost 100 people have been arrested and charged as a result of evidence obtained from Sky ECC communications and passed on by the French and Dutch, for crimes involving drug trafficking, murder, and kidnapping. On the same day as Saric was arrested in the Serbian capital, police in neighbouring Croatia rounded up 10 in a joint operation with police in France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Austria and Spain.

Cheered on by tabloids, authorities in various Balkan countries claim they are taking the fight to the organised crime gangs. Case closed, apparently.

Behind the headlines, however, experts question whether authorities have the know-how or will to follow the myriad leads exposed by the Sky ECC breach, wherever they might take them.

In only a few of the cases in the Balkans have indictments been confirmed by the courts. And though investigations have revealed links between public officials and crime figures, so far only a few of the former have been indicted.

Legal experts, meanwhile, warn of concerns about the legality of how the data – from Sky ECC and a similar breach of EncroChat in 2020 – is handed over and stored, questions that threaten its admissibility in court.

“For the EncroChat case, for example, it was not clear where the raw data exactly came from and if the raw data had been changed in any way after it had been collected from the service,” said Professor Dennis-Kenji Kipker, a board member at the European Academy for Freedom of Information and Data Protection, EAID.

“This is generally a problem when it comes to court trials,” he told BIRN. “When the raw data, digital data is being used, it can be changed and the data authenticity and the data integrity cannot be guaranteed.”

Big potential for probe into judges

Two days before Saric’s arrest, police in Montenegro arrested one of their own – Dalibor Medojevic, until recently the head of the police’s economic crime department.

Medojevic was arrested on suspicion of creating a criminal organisation and abuse of office. A source with knowledge of the case told BIRN that he was arrested on the basis of Sky ECC communications.

Media, citing prosecution sources, reported that Medojevic had been in communication with members of a prominent crime gang called the Skaljari clan, one of two rival gangs that originated in the Montenegro coastal town of Kotor, and providing them with information about the investigation against them.

In December, another police officer, Darko Lalovic, was arrested, this time after he was found to have been in communication via Sky ECC with members of the Kavac clan, the rival to the Skaljari, media reported.

Lalovic had been in charge of security for the president of Montenegro’s Supreme Court.

This month, media in Montenegro published a leaked transcript of a Sky ECC conversation allegedly between him and Milos Medenica, the son of Vesna Medenica, a former president of the Supreme Court, in which they appear to discuss smuggling cocaine and cigarettes through the port of Bar, a notorious smuggling hub. Milos appears to say his mother would protect them. Authorities say Milos Medenica left Montenegro after the arrest of Lalovic, who remains in custody on organised crime and drug charges.

Vesna Medenica herself was arrested on April 17 at Podgorica airport on suspicion of abuse of office. She previously denied any wrongdoing.

In terms of the Skaljari and Kavac themselves, Sky ECC evidence has played a part in cases against Skaljari members Milo Jovanovic and Radovan Stanisic, alleged Kavac leader Slobodan Kascelan and gang member Petar Djurovic. In the first, Jovanovic and Stanisic are awaiting trial on charges of creating a criminal organisation; Kascelan is in detention on suspicion of murder; and Djurovic was arrested in December and charged by prosecutors with murder.

Dejan Milovac, director of the anti-graft NGO MANS, said the potential offered by the Medenica case was huge, providing the special prosecutor’s office is willing to run with it and resist any political pressure it might face.

“If the validity of the allegations from Sky communication is proven, i.e. trading in influence in the way described by Milos Medenica, I think that there is a huge space for an investigation against Medenica to be launched in other cases where she was believed to use a similar modus operandi,” Milovac told BIRN.

“It would be a pity not to use the opportunity to clean up the judicial organisation that Medenica may have relied on or used to trade in influence through the processing of this case.”

Similarly, in Bosnia, Sky ECC evidence led to the arrest of 16 people in the area of Zvornik, on Bosnia’s eastern border with Serbia, in April.

In February, N1 TV quoted Dragan Lukac, interior minister of Bosnia’s predominantly Serb-populated Republika Srpska entity, as saying that some police and intelligence officers had Sky ECC installed on their phones.

Serbia’s ‘Soprano’

In the Saric case, no one has been held to account over his access to an array of communication devices behind the walls of one of the highest-security establishments in Serbia.

BIRN asked Serbia’s Directorate for the Execution of Criminal Sanctions, which runs the country’s prisons, how it was that Saric would have access to such devices but had not received a reply by the time of publication.

Before Saric’s arrest, the Sky ECC takedown’s biggest scalp was that of Veljko Belivuk, the alleged leader of a brutal crime gang that appears to have had associates in public office. Indeed, it had a direct line to a state secretary in the interior ministry called Dijana Hrkalovic, since dismissed and charged with trading in influence.

Belivuk, better known as ‘Velja Trouble,’ and 19 gang members were arrested in February 2021. Eventually, 30 were indicted in July 2021 on a string of charges including murder.

According to the indictment, one of the victims, Lazar Vukicevic, was killed and cut up, his body parts ground into bits and tossed into the Danube river in Belgrade.

In the process, they chatted on Sky ECC. At 7.48 p.m. a message is sent saying, “Lads, everything’s alright. He’s tied up.” They had wrestled a gun out of his hands, the message said, followed by a picture of the victim tied up.

A user identified in the indictment as Belivuk’s lieutenant, Marko Miljkovic, replies: “Well done bro, what can I tell you, bravo, this one also had a prangija today, so we fixed it right away. E awesome, brother, please, I’m here with Soprano.” A prangija is Serbian slang for a gun. Soprano, the indictment said, was Belivuk.

A voice is quoted as saying, “Let him suffer the most,” while another tells the perpetrators to “give 102 per cent of yourselves.”

The case against Belivuk and his co-accused is still in the stage of preliminary hearings.

Fair trial concerns

On April 13, prosecutors filed another indictment against Belivuk, Miljkovic and 10 others, charging them with another two murders. The indictment is yet to be confirmed by the court.

The Serbian interior ministry did not reply to questions concerning its involvement in Sky ECC-related investigations. The evidence against Belivuk’s group relies mainly on the Sky ECC crack, which is cited throughout the indictment.

Nina Nicovic, a lawyer and Serbian judicial expert, said such evidence can only be considered solid proof if the interlocutors and timeline can be determined.

“Evidence obtained through Sky can be important only if the expertise in Serbia has unequivocally determined who communicated, as well as the place and time,” Nicovic told BIRN. “Otherwise, it can only serve as a clue to other evidence.”

A German court has already ruled such evidence admissible, after France sent to Germany data obtained from the hack of EncroChat.

“From a French perspective it was not clear where the data came from and which technical devices have been used to compromise the chat services or the chat company, EncroChat, that offered these services,” said Kipker.

But he questioned the ruling of the German Federal Court, telling BIRN: “They do not see that we have a long chain of evidence here, a digital chain of evidence, which can hardly be described as traceable in terms of data authenticity and data integrity.”

Laure Baudrihaye-Gerard, Europe legal director for Fair Trials, a UK-registered criminal justice watchdog, also voiced concern.

“Lack of access to information about how information was obtained, analysed and processed makes it impossible for accused people to challenge the use of the information obtained from the apps as evidence,” Baudrihaye-Gerard told BIRN by email. “It also means courts – who are meant to review the legality and reliability of information before admitting it as evidence – cannot exercise their role and offer judicial protection.”

“By removing the ability to scrutinise evidence derived from operations involving EncroChat and Sky ECC, we are giving law enforcement a blank cheque and setting a dangerous precedent.”

In Belgium, the lawyer of a suspect arrested as a result of the Sky ECC breach appealed to the Court of Cassation, arguing that his right to a fair trial had been violated because he was not given access to all intercepted information.

The court ruled, however, that, “in the current state of criminal justice there are no grounds to doubt the regularity of the Sky data”, Belgian newspaper De Tijd reported.

“The secret nature of the investigation in the Sky file can currently be invoked in order to not yet disclose all available information to the person concerned,” it said.

Nicovic also stressed the key role played by IT forensic experts, who are in short supply in the Balkans.

“In my experience, there are only a few IT forensic experts that can work on such cases,” she said. “They are crucial because they have a very difficult job of proving the origin and authenticity of data that may turn out to be crucial in a criminal case.”

Nicovic said that, even if national authorities have not initiated a case, they have the right to investigate any information provided to them by competent authorities of another country.

“They must initiate pre-investigation, i.e. investigative actions and put that data in the context of local legislation, i.e. all the rules applicable to the examination of the veracity of such data,” she said. “This means that this data will have to go through all the checks required by the Serbian criminal legislation to be acceptable in court.”