What’s new? A three-year ceasefire in rebel-held Idlib has saved countless lives and allowed the main insurgent group, Hei’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), to redirect its efforts from fighting the regime to dismantling ISIS and other jihadist cells. Yet uncertainty regarding Türkiye’s Syria policy may threaten the relative peace and hamper humanitarian relief.

Why does it matter? Since Türkiye’s military presence is key to preserving the Idlib ceasefire, a turnaround could allow ISIS and other jihadist groups to stage a comeback, creating new conflict and jeopardising the international response to, especially, the 6 February 2023 earthquakes that devastated parts of northern Syria and caused massive new displacement.

What should be done? Türkiye should aim to strengthen the 2020 ceasefire. Western governments should support those efforts and build on three years of relative calm to bolster humanitarian aid. They should also explore opening communication channels to HTS to better grasp the threat posed by ISIS and other transnational militants in north-western Syria.

Executive Summary

Western leaders worry that rebel-held Idlib in north-western Syria remains an operating base for transnational jihadists. Some U.S. officials describe it as the world’s largest al-Qaeda safe haven; others suspect collusion between Hei’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the former al-Qaeda affiliate that rules Idlib, and the Islamic State (ISIS), particularly after the U.S. killing in February 2022 of ISIS leader Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Quraishi in an Idlib hideout. In reality, HTS has forsworn transnational jihad, gone after ISIS and al-Qaeda cells, and subdued most other jihadists. ISIS endures in Idlib only because HTS lacks the capacity to quash it fully. To prevent ISIS from rebounding if conditions change, foreign powers should endorse Türkiye’s efforts to preserve the 2020 ceasefire and provide more aid to the region. Opening communication channels with HTS could deepen knowledge of ISIS activities, and improve the humanitarian response to emergencies, like the 6 February 2023 earthquakes across the Turkish border.

HTS has suppressed rivals in Idlib primarily in pursuit of self-preservation and dominance in the province. Its priority is to forestall further regime offensives, which with Russian air support had been threatening its de facto rule. A ceasefire, negotiated in March 2020 between Russia and Türkiye, along with the insertion of Turkish troops, put a halt to those assaults, giving HTS space to move against groups that challenged its hegemony. It has dealt harshly with any that defy the ceasefire or its ban on operations abroad or against Turkish forces in Idlib. Freelance attacks on Russian or regime positions could bring retaliation from Damascus and Moscow, costing HTS its control of Idlib. Allowing jihadists to plan foreign operations from Idlib would hurt HTS’s attempts to secure aid for the province and recast itself as a reliable negotiating partner. Such operations would strain its crucial, yet tenuous relations with Türkiye, the ceasefire’s de facto guarantor, and could also trigger Western strikes and sanctions.

” HTS [Hei’at Tahrir al-Sham] appears to have crushed most jihadist groups in Idlib that refused to submit to its leadership and rules. “

For now, HTS appears to have crushed most jihadist groups in Idlib that refused to submit to its leadership and rules. Likewise, its security apparatus has mostly succeeded in dismantling active ISIS and al-Qaeda cells and limiting further jihadist infiltration. Yet gaps remain. These include the volatility of the military situation in and around Idlib, insufficient international humanitarian support, and the constant movement of displaced people into and throughout the area. ISIS has exploited these gaps, just as it has taken advantage of its adversaries’ weaknesses in other parts of Syria. While the group is lying low, using the north west solely as a place to conceal cadres, any serious disruption could let it resurge.

Several steps can help prevent this eventuality. Türkiye should continue to work with Russia to consolidate the ceasefire. Ankara benefits from the ceasefire in several ways – not least in that another regime offensive would provoke more displacement toward the Turkish border – but the north west’s relative calm is also the best check on ISIS and al-Qaeda re-emerging. From its side, HTS should continue to suppress groups that violate the ceasefire or its ban on launching operations abroad or against Turkish forces in Idlib. It should avoid using these groups as a bargaining chip with the West.

Western countries also have a vital part to play. They should back Türkiye diplomatically in its military role upholding the ceasefire. They should also give more aid to Idlib, going beyond simply life-saving humanitarian assistance, provided that HTS keeps its hands off these supplies, as it has done with the UN provisions now entering Idlib. The February 2023 earthquakes in Türkiye have underscored the pressing need for the West to step up support to Syria’s north west, lest Ankara wind up having to shoulder the entire burden of rebuilding the region and aiding its people. Western countries might also open informal channels of communication to HTS in order to get a better sense of transnational militant activity in Idlib and negotiate better aid access to the suffering population.

Istanbul/Brussels, 7 March 2023

I. Introduction

Islamist insurgents came to dominate the rebellion in Syria’s north west only gradually. As in other parts of the country, most of the armed groups that sprang up in the north west in the 2011 uprising’s first months had no distinct political or ideological project beyond opposition to Bashar al-Assad’s regime. As the war dragged on, however, groups professing an explicitly Islamist – and, often, jihadist – ideology gained ground. Memories of the Islamist movements of the 1980s, which the regime had brutally repressed, made parts of the population susceptible to Islamist rhetoric.[1] Gulf-based funders, many of whom had Islamist leanings, contributed to the trend, as did the foreign fighters filtering through the porous borders with Iraq and Türkiye. Islamist groups cemented their dominance in the north west by means of organisational and military prowess.[2] Over time, Jabhat al-Nusra, which at first was affiliated with al-Qaeda, became one of the strongest forces in the area.

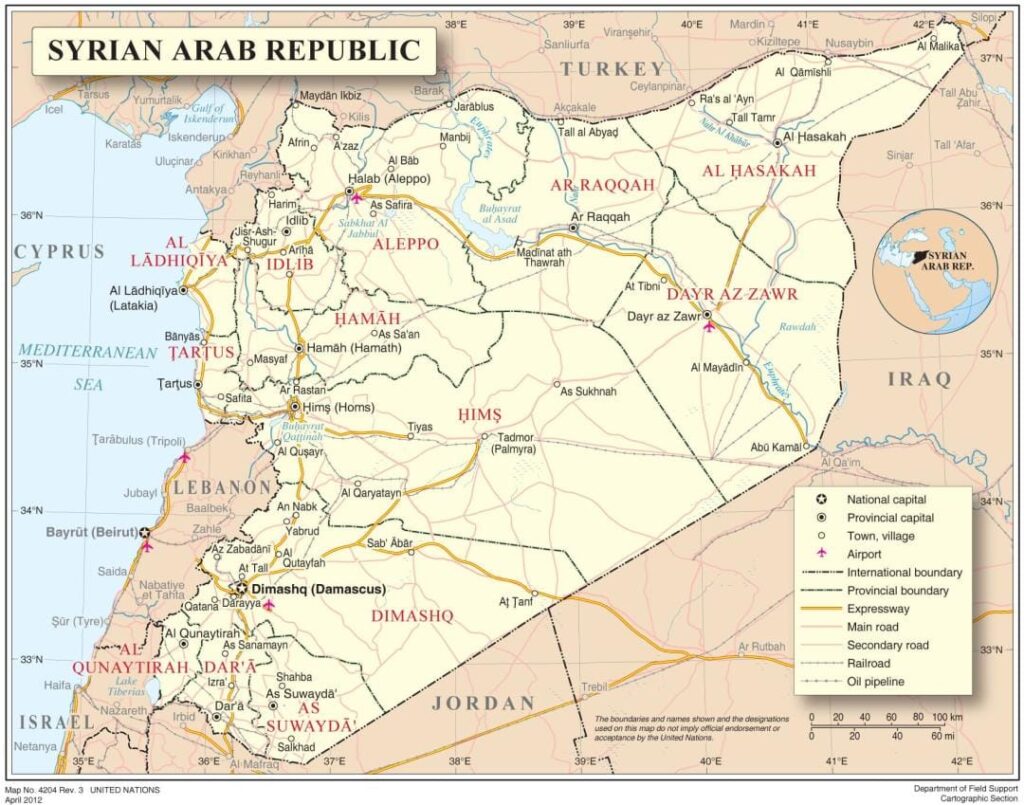

In the first half of 2015, jihadist groups took the lead in a sustained anti-regime offensive enabled by enhanced coordination and greater external support. By that July, the rebels had expanded their control to all of Idlib, a key north-western province, and swathes of the adjacent Hama, Lattakia and Aleppo governorates. These gains, which coincided with Islamic State (ISIS) advances in central Syria, caused concern among the Assad regime’s backers, chiefly Russia and Iran, that its military was on the brink of collapse. Russia hastened to prop up its defences later that year.[3]

[1] Jonathan Spyer, “Defying the Dictator: Meet the Free Syrian Army”, World Affairs, vol. 175, no. 1 (May-June 2012).

[2] See Crisis Group Middle East and North Africa Report N°131, Tentative Jihad: Syria’s Fundamentalist Opposition, 12 October 2012.

[3] Samuel Charap, Elina Treyger and Edward Geist, “Understanding Russia’s Intervention in Syria”, RAND Corporation, 2019.

” By mid-2018, the UN and many individual countries had designated HTS as a terrorist organisation. “

Russia’s move allowed regime forces to stabilise the war’s various fronts and then roll back rebel gains, first by retaking Aleppo in 2016 and then by launching extended offensives in the south and north west (2017-2018 and 2019-2020). During the same period, Jabhat al-Nusra, which in 2016 severed its ties with al-Qaeda, rebranded itself as Jabhat Fatah al-Sham before merging the next year with smaller groups in an alliance called Hei’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). This alliance consolidated control over the shrinking rebel enclave, establishing what it called a “salvation government”. It moved to bring other Islamist groups under its thumb, crushing those who resisted, and fought off attempts by ISIS to gain a foothold in the area. By mid-2018, the UN and many individual countries had designated HTS as a terrorist organisation – as they had Jabhat al-Nusra before it.[1]

HTS remains the de facto authority in Idlib, but it is not the only Islamist militant organisation in the region.[2] This report maps the jihadist groups operating in Idlib, with the aim of offering a better understanding of these groups’ current nature and reach. The report delves into how HTS has been dealing with transnational jihadists in Idlib and describes the limits of those efforts. It is based on more than 50 interviews in Idlib and its environs, including with HTS leaders and security officials, as well as defectors from the group and opponents of it, along with Turkish, U.S. and other foreign officials familiar with dynamics on the ground.

[1] “Security Council ISIL (Da’esh) and Al-Qaida Sanctions Committee Amends One Entry on Its Sanctions List”, press release, UN Security Council, 5 June 2018. This report differentiates HTS and factions aligned with Türkiye from other Salafi-jihadist groups. The former describe themselves in Arabic as jama‘at mujahida (groups engaged in jihad), implying that armed struggle is a means toward an end, and not an end in itself, and that they see means other than military activities as ways of achieving their goals. In military terms, they confine themselves strictly to fighting the Syrian regime, distancing themselves from transnational jihadist projects. By contrast, groups that define themselves as jama‘at jihadiya (jihadist groups) put the military dimension of jihad first and also support or engage in violent operations outside Syria. HTS’s rule in Idlib is not jihadist.

[2] Areas under HTS control are often referred to as “greater Idlib”, a swathe of land that includes Idlib and small parts of Aleppo, Hama and Lattakia provinces.

II. Idlib as Safe Haven and Holding Pen

The situation in Idlib today has its roots in events in 2015. Syrian rebels, with Jabhat al-Nusra in the lead, took Idlib city that March and marched deeper into northern Syria in the following months.[1] The Russian intervention on the regime’s side in September turned the tide of the war. Rebel-held parts of Aleppo fell one by one over the course of 2016, in keeping with a pattern that had developed in Homs two years earlier: the regime laid protracted siege to these areas; when it prevailed, all the rebel fighters and residents who were unwilling to surrender escaped or were displaced westward to Idlib and its environs.[2] People fleeing the international coalition’s campaign to roll back ISIS in eastern Syria added to the massive displaced population crammed into Idlib. Repeated Russian and regime aerial attacks, combined with ground campaigns, made things worse. Türkiye sealed its border bit by bit, making crossings more and more difficult. Over three million people, more than half of them displaced from elsewhere, remain trapped in dire humanitarian conditions in Syria’s north west.[3]

The regime-Russian offensives also triggered deepening Turkish military involvement.[4] In early 2020, regime forces appeared to be closing in on Idlib city, sending more refugees toward the Turkish border. Ankara responded by sending soldiers into Syria’s north west, and in late February, Turkish and Syrian troops engaged in direct confrontations, with Türkiye employing drone and artillery strikes that killed hundreds on the other side.[5] Turkish action paved the way for a ceasefire, concluded between Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin, nominally acting on Assad’s behalf, in the Russian town of Sochi on 5 March 2020.[6] The Turkish military build-up that remains in place today suggests that if the regime attempts to take the remainder of Idlib, it could meet a strong Turkish response.[7] This deadlock remains a key obstacle to normalisation of relations between Ankara and Damascus.[8]

Türkiye has ample reason to resist regime advances into Idlib. While its endgame in northern Syria is unclear, Ankara almost certainly seeks to preserve a measure of influence in the area, particularly to prevent regime offensives that would push hundreds of thousands of Syrians across the border at a time when popular sentiment is turning against the refugees already in the country.[9]

Türkiye is thus in a delicate position. By keeping the Syrian regime out of rebel-held Idlib, it has become the implicit protector of the groups in control of the area. Among these, HTS is the most powerful, having subjugated or expelled most of the remaining factions, including other jihadists. Yet Türkiye, along with the UN and others, has designated HTS as a terrorist organisation. All the Idlib ceasefires concluded between Ankara and Moscow since 2017 have included pledges to “fight terrorism”, which in principle commit Türkiye to cracking down on HTS. Moreover, several political currents in Türkiye, including non-Islamist nationalists and Eurasianists – secular nationalists who want to turn away from the West and favour rapprochement with countries such as Iran and Russia – want the government to eschew engagement with HTS.

[1] Aron Lund, “Syrian rebels capture Idlib”, Syria Comment (blog), 28 March 2015.

[2] “Aleppo Syria battle: Evacuation of rebel-held east”, BBC, 15 December 2016.

[3] “Northwest Syria – Factsheet”, UN Office of the Coordinator for Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), 9 August 2022; and “In a Syrian rebel bastion, millions are trapped in murky, violent limbo”, The New York Times, 27 August 2021.

[4] On the first phase of Turkish deployment, see Crisis Group Middle East Briefing N°56, Averting Disaster in Syria’s Idlib Province, 9 February 2018.

[5] “Turkey declares major offensive against Syrian government”, The New York Times, 1 March 2020; and “Operation Spring Shield”, Global Security, 30 June 2021.

[6] “Russia, Turkey agree ceasefire deal for Syria’s Idlib”, Reuters, 5 March 2020.

[7] In 2021, there were at least 10,000 Turkish soldiers in north-western Syria, according to Turkish officials. Crisis Group interviews, Ankara, 2021.

[8] Crisis Group interviews, Turkish officials, Ankara, 2022.

[9] Crisis Group interviews, Turkish officials, Ankara, 2021-2022.

” HTS, despite its terrorism designation, has evolved. “

Yet HTS, despite its terrorism designation, has evolved. It has distanced itself from global jihadism, while projecting a Syrian nationalist orientation. It presents itself as an actor able to exercise local governance, provide security and pragmatically engage with regional and other outside powers.[1] The Turkish officials handling the Syria file in Ankara, for their part, believe that HTS no longer has transnational goals or affiliations, having dedicated itself solely to governing Idlib and defending it from regime offensives.[2] They also think that HTS, having shown it will abide by the ceasefire arrangement in Idlib, could be useful in containing or eliminating transnational jihadists (including ISIS and al-Qaeda elements) who might stir up trouble in the area or beyond.[3]

Yet the organisation’s origins in the milieu that spawned ISIS and its own previous allegiance to al-Qaeda cast a long shadow. Some Western officials believe that HTS may return to its jihadist roots when conditions change or that it is turning a blind eye to transnational jihadists’ presence in areas under its control.[4] Both the first self-declared ISIS caliph and the second have met their demise while hiding in Idlib, feeding concerns that, regardless of HTS’s transformation, the area may provide a safe haven where ISIS or al-Qaeda members can regroup for new attacks in Syria and beyond.[5] Not even most Western officials who accept that HTS has genuinely moved away from al-Qaeda and transnational militancy see much value in changing policy toward the group.[6] Due to the resulting chilling effect, most humanitarian aid providers have shied away from working in Idlib.

[1] See Dareen Khalifa, “The Jihadist Factor in Syria’s Idlib: A Conversation with Abu Muhammad al-Jolani”, Crisis Group Commentary, 20 February 2020; and “Syrian militant and former al Qaeda leader seeks wider acceptance in first interview with U.S. journalist”, Frontline (PBS), 2 April 2021.

[2] Crisis Group interviews, Turkish officials, Ankara, 2021-2023.

[3] Crisis Group interviews, Turkish officials, Ankara, 2020-2021.

[4] Crisis Group interviews, U.S. officials, Washington, July 2022; Western officials, by telephone, September 2022; and British official, London, May 2022.

[5] The first self-declared caliph, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, was killed in a U.S. raid in Idlib in October 2019. The second, Abdullah Qardash, was killed in February 2022. For an example of the media coverage generated by Qardash’s killing, see Anchal Vohra, “Rebel-held Syria is the new capital of global terrorism”, Foreign Policy, 15 February 2022. A British official said: “Is HTS really going after ISIS? It seems to us like they are accommodating them”. Crisis Group interview, London, May 2022.

[6] “Syrian militant and former al Qaeda leader seeks wider acceptance in first interview with U.S. journalist”, Frontline (PBS), 2 April 2021.

III. Shades of Jihadism in Idlib

Among the plethora of armed groups seeking to overthrow the Assad regime since 2011, jihadist formations of various hues came to dominate the forces in Idlib. While some of these groups predate the conflict, most formed after 2011 around individual commanders or particular nationalities of foreign fighters. The degree to which they pursued transnational agendas – “jihad beyond Syria”, to use their phrase – varied. A few had previously been associated with al-Qaeda. The story of the past few years is one of HTS using breaks in fighting the regime to progressively eclipse all its rivals. First, it targeted more mainstream Islamist rebels, and then it went after jihadists, with whom differences in strategy eventually put it on a collision course.[1] The lull after the 5 March 2020 ceasefire provided breathing space for HTS, after which it crushed, or at least decimated, the other jihadist groups that might have challenged its leadership.

As it found its footing as the strongest faction in north-western Syria, HTS played a complicated game balancing enmity and civility with both the local non-jihadist factions and the hardline Islamist and jihadist groups. While HTS was still Jabhat al-Nusra, it sought to weaken or even eliminate groups it denounced for receiving support from the U.S. Then, as HTS, it fought the groups it viewed as the most potent threats to its ideological and political dominance. Its approach amounted to a dual strategy of suppression and co-optation. Between 2017 and 2018, its main objective was to battle the Turkish-aligned groups it considered rivals in order to block consolidation of an alternative coalition that could gain local and international traction.[2] To that end, HTS fought the Islamist faction Ahrar al-Sham, the strongest other group at the time, and its allies. These groups were forced to recognise HTS control of the province, transfer their administrative structures – including courts of justice and prison facilities – to the HTS-supported “salvation government”, and keep only weak military forces in Idlib.[3]

At this point, HTS did not consider other jihadists to be threatening adversaries. With the regime gaining a foothold in greater Idlib in late 2017, HTS needed smaller militant groups to fight on its side. Likewise, during the 2019-2020 regime offensive and rapid collapse of rebel lines, HTS was more than willing to work with other factions – both jihadist and Islamist – whose fighters’ skills proved to be useful on the front lines.[4] Its leaders seemingly did not want other groups or the general population to accuse them of putting factional infighting above the war with the regime – a major criticism other rebels had levelled at them previously.

[1] Christopher Solomon, “HTS: Evolution of a Jihadi Group”, Wilson Center, 13 July 2022.

[2] See Jerome Drevon, “Ahrar al-Sham’s Politicisation during the Syrian Conflict” in Masooda Bano (ed.), Salafi Social and Political Movements: National and Transnational Contexts (Edinburgh, 2021).

[3] Crisis Group interviews, Ahrar al-Sham leaders, Turkey, 2019-2020.

[4] Crisis Group interviews, HTS leaders, Idlib, 2019-2020.

” HTS tolerated most factions that were willing to fight the regime. “

As such, HTS tolerated most factions that were willing to fight the regime. The only two groups that HTS eliminated before 2020 were the jihadist Jund al-Aqsa, which it dismantled in February 2017 after accusing it of ties with ISIS, and Nur al-Din al-Zinki’s faction, which it expelled from Idlib in January 2019.[1] It allowed all others to operate in the province with few restrictions, viewing any threat they might pose as secondary to the imminent dangers arising from ISIS and the regime.[2]

As anti-regime fighting came to a halt in March 2020, however, HTS turned its guns on other jihadists.[3] Tensions with these groups had been building since Jabhat al-Nusra broke with al-Qaeda in 2016, a split that became more explicit in 2017, and began accommodating the Turkish army in Idlib.[4] After March 2020, HTS used the ceasefire to subjugate hardline groups that accused it of abandoning transnational jihad and opposed its new accommodation with Türkiye. Publicly, HTS cites these groups’ attempts to undermine the ceasefire or maintain independent administrative structures as its main justification for the crackdown, rather than ideological disputes.[5]

The jihadist groups operating in Syria today fall into three general categories: those that have merged into the HTS military wing; those that have acquiesced to the group’s authority in the HTS-led joint operations room, called al-Fatah al-Mubin (Clear Victory); and those that remain independent and often at odds with HTS. The vast majority of Idlib factions belong to the first two categories, while HTS works to contain the few tiny ones in the third.

HTS dealt with each jihadist group that opposed its break with al-Qaeda based on how much risk it thought the group posed to its rule. Aside from ISIS, HTS saw the main threat in 2020 as coming from the al-Qaeda offshoot Hurras al-Din.[6] After HTS left al-Qaeda, Hurras formed as a loose front of former Jabhat al-Nusra commanders antagonistic to HTS, rather than a cohesive structure with a clear agenda.[7] The antagonism was rooted in strategic differences and personal rivalries, but it had an ideological undertone related to the increasing pragmatism within HTS. Hurras did not declare HTS members to be non-believers, as ISIS did, but it said the group’s behaviour was tantamount to “acts of non-belief”.[8] HTS did not consider the group to be capable of undermining its control of Idlib, yet it worried nonetheless that Hurras might kill major HTS figures, perhaps winning over lieutenants who doubted the leadership’s new political direction.[9]

HTS brought Hurras gradually to heel. It first compelled the group to commit not to use Syria as a launching pad for operations abroad and to recognise the “salvation government” and its courts. It prohibited Hurras from setting up checkpoints or staging attacks on the regime.[10] This agreement lasted until a few months after the March 2020 ceasefire, when Hurras defied it by creating a new operations room called Fa-Ithbatu (So Be Steadfast) in alliance with HTS defectors and other hardliners. At this time, Hurras also placed checkpoints on roads in Idlib.[11] In response, HTS declared that only it or al-Fatah al-Mubin, which it leads together with Turkish-backed factions (though it is the dominant force), could conduct military operations in Idlib.[12]

[1] HTS also criticised Jund al-Aqsa for excommunicating other factions and refusing to settle disagreements in shared courts. “A warning to the group Liwa al-Aqsa”, HTS, 13 February 2017 (Arabic). Zinki had joined HTS at is founding but left amid clashes between it and groups led by Ahrar al-Sham. Crisis Group interview, Idlib, January 2020. HTS communiqués accused Zinki of attacking the group. “The aggressor will meet his deserved fate”, HTS, 6 May 2018 (Arabic).

[2] Crisis Group interviews, Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, HTS general commander, and Abul-Hassan 600, HTS military leader, Idlib, July 2020.

[3] Zulfiqar Ali, “Syria: Who’s in control of Idlib?”, BBC, February 2020.

[4] See al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri’s video criticism of HTS, Site Intelligence Group, 2017 (Arabic). Some of these criticisms were also articulated by Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi, who is close to al-Qaeda and Hurras al-Din commanders. See Cole Bunzel, “Diluting jihad: Tahrir al-Sham and the concerns of Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi”, Jihadica (blog), 29 March 2017. Prominent religious scholars who served as links between Hurras and al-Qaeda leaders al-Zawahiri and Sayf al-Adel report that the latter were angry at HTS, viewing its split from al-Qaeda as a betrayal. One of them added that HTS had made too many concessions to other opposition groups and could no longer be trusted because it was changing its ideological positions. Crisis Group interviews, Amman, May 2022.

[5] Crisis Group interviews, HTS commanders, Idlib, 2020-2021.

[6] Crisis Group interviews, Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, HTS general commander, and Abul-Hassan 600, HTS military leader, Idlib, 2019-2020.

[7] Crisis Group interviews, Abul-Hassan 600, HTS military leader, Idlib, 2019-2020. Hurras was created in 2018, a year after HTS, at a time when the latter was busy fighting insurgents led by Ahrar al-Sham. HTS officials insist that Hurras was never ideologically cohesive, as it was badly divided over what position to adopt on HTS and Türkiye. As an organisation, Hurras opposed HTS-Turkish ties, but its leaders and commanders disagreed over whether to declare HTS made up of non-believers and thus subject to attack. Crisis Group interview, HTS security official, Idlib, September 2022.

[8] In a communiqué issued two months after the 2020 ceasefire, Hurras leader Abu Humam al-Shami pronounced anyone who lets Turkish troops into Idlib, protects them and fights alongside them to be a non-believer – without mentioning HTS by name. He argued that Türkiye should itself be labelled kafir (non-believing), not just as a secular state, but also because it signed the Sochi agreements with Russia, which commit both countries to fighting jihadists, and supported the Geneva constitution-drafting process, which he deemed contrary to Islamic law. Abu Humam al-Shami, “Al-Ma’oul al-Haddam” (The Destructive Pickaxe), 8 May 2020 (Arabic). Under pressure from other Hurras commanders, Shami later denied authoring the communiqué. Researchers close to Hurras religious leader Sami al-Uraydi claim that the group’s leaders declared HTS non-believers only in private. Crisis Group interviews, Amman, 2022. HTS security officials believe Shami has not explicitly designated HTS as kafir. Crisis Group interviews, Idlib, September 2022. A prominent jihadist close to al-Qaeda and Hurras, Maqdisi, had previously criticised HTS for “diluting jihad” by accepting ceasefires in Idlib and repressing other militants. Bunzel, “Diluting jihad”, op. cit. Maqdisi also forbade fighters from joining the HTS security services. See “HTS disavows Maqdisi and accuses him of sowing discord”, Syria TV, 11 October 2020.

[9] Several HTS sub-groups and commanders threatened to leave the group after it started arresting fighters close to al-Qaeda. For example, “Important communiqué from a group of HTS leaders”, undated (Arabic). HTS subsequently prohibited members from breaking away, whether to found a new faction or join an existing one, without its agreement. See “Announcement”, HTS, 22 February 2020 (Arabic).

[10] Crisis Group interviews, Abu Mohammed al-Jolani and Abul-Hassan 600, Idlib, 2019-2010. The most senior HTS religious scholar, Abd al-Rahim Atoun, mentioned some of these conditions in a message to al-Qaeda. See Atoun, “Response to the communiqué of al-Qaeda”, June 2020 (Arabic). HTS and Hurras leaders discussed the conditions imposed by HTS on the group early on in a series of texts and communiqués published online. See Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi, “The Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham-al-Qaeda Dispute: Primary Texts (IX)”, Pundicity (blog), 5 February 2019.

[11] “‘Coordination of Jihad’… A new organisation headed by ‘Ashdaa’ joins the anti-regime fight in Idlib”, Al-Modon, 9 February 2020 (Arabic).

[12] The other two strong factions in al-Fatah al-Mubin are Ahrar al-Sham and Faylaq al-Sham, which had to concede dominance to HTS despite much internal opposition. Crisis Group interview, former Ahrar al-Sham leader, Antakya, August 2022. In June 2020, HTS forbade new operations rooms or factions, giving a monopoly on military force to al-Fatah al-Mubin. See “On the unification of military efforts”, HTS, 26 June 2020 (Arabic).

” HTS … banned the establishment of new military formations. “

HTS then banned the establishment of new military formations, using this measure to crack down on the Hurras alliance and associated groups. In mid-2020, HTS raided Hurras headquarters, detained several of its leaders, and forced it to shut down its bases and checkpoints.[1]

HTS dismantled Hurras and its joint operations room in just a few days. The speed with which Hurras fell apart reflected its organisational weakness (and, by extension, that of al-Qaeda) in Idlib. That said, while the group was incapacitated in the north west, it may have been able to carry out isolated operations elsewhere in Syria, at least at first.[2] Several Hurras leaders remain at large, including its commander, known as Abu Humam al-Shami, and its highest religious authority, Sami al-Uraydi. HTS claims it is not actively pursuing them but would arrest them if they left their hiding spots, believing that leaving Hurras alive but feeble is better than imprisoning its leaders, which might bring more capable replacements to the fore.[3]

HTS then extended its campaign to the groups previously allied with Hurras al-Din. It swiftly pulled the organisations to pieces but allowed a few leaders to stay in Idlib. Two of these groups, Tansiqiyat al-Jihad and Liwa al-Muqatilin al-Ansar, are now defunct, while Jabhat Ansar al-Din, which came into being early in the Syrian war, has just a small number of fighters left.[4]

Over the course of 2020-2021, HTS also got rid of groups that had split off from Hurras. Disagreements among Hurras commanders about whether to attack HTS and Turkish forces had prompted dissidents to create factions called Saraya Abu Bakr al-Sadiq and Saraya Abdullah bin Omar Unais. These two small groups seemed to have shared an organisational structure, but the first attacked Turkish forces and the second went after HTS in a de facto division of labour.[5] They also occasionally obtained money or weapons from ISIS cells in Idlib, though they did not pledge allegiance to the organisation. Another group called Kataeb Khattab al-Shishani, which also claimed several attacks, mainly on Russian and Turkish patrols in Idlib, is part of the same cluster of Hurras spin-offs.

Its success with Hurras and lack of backlash from other hardliners in Idlib bolstered HTS’s confidence to tighten its grip on other jihadist outfits. It pursued any group that defied its decrees, detaining the leaders (and often the main commanders) before releasing some of them on condition that they leave the province or refrain from any public activity. It framed its crackdown as a matter of “war and peace”, seemingly so as to avoid having to outlaw factions over ideological disagreements.[6] The main requirement was that the other group acknowledge HTS’s monopoly on force and obey its military orders.

[1] Sirwan Kajjo, “Powerful Islamist group intensifies crackdown on jihadists in Syria’s Idlib”, Voice of America, 28 June 2020.

[2] Hurras later claimed responsibility for attacks on a Russian base in Raqqa and a bus carrying members of the regime’s elite Republican Guard in Damascus. See “Hurras al-Din lays claim to deadly Damascus bus blast”, COAR Global, 9 August 2021. Some observers suggest that the bus explosion was caused by an electrical malfunction, rather than a Hurras bomb. Crisis Group telephone interviews, Syria analysts, August 2021.

[3] Crisis Group interview, HTS security official, Idlib, September 2022. The top HTS leader mentioned that continuing to arrest Hurras figures would bolster the group’s claim to be oppressed, perhaps in turn winning it more popular sympathy. Crisis Group interview, Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, Idlib, February 2022.

[4] Fa-Ithbatu was created in June 2020 with four other dissident groups, two of which were formed by ex-HTS commanders: Tansiqiyat al-Jihad, led by Abu Abd Ashida, and Liwa al-Muqatilin wal-Ansar, led by Abd al-Malek al-Tilly. Ashida is a former Ahrar al-Sham commander who later joined HTS. Tilly is a former HTS leadership council (follow-up committee) member who disagreed with Jolani’s policy of rapprochement with Türkiye. The other two groups in the operations room were Ansar al-Islam and Jabhat Ansar al-Din, led by Abu Abdullah Fajr. See “‘Coordination of Jihad’”, op. cit. Some of these groups consist of only a few people.

[5] HTS internal security commanders told Crisis Group that some Hurras dissidents wanted to attack only Turkish forces, while others wanted to attack both Turkish troops and other parts of the armed Syrian opposition. To please both sides, they decided to create two groups: Saraya Abu Bakr al-Sadiq and Saraya Abdullah bin Omar Unais. Crisis Group interviews, Idlib, September 2022. In a video entitled “Ghulu: The Poisoned Dagger”, published in December 2022, HTS’s internal security services aired excerpts from staged interviews with the Saraya Abu Bakr al-Sadiq leader Wadah al-Hamawi and several of the group’s rank and file following their arrest. In his interview, Hamawi said the two groups share an organisational structure and differ only in whether they fight just Turkish troop or HTS as well. He also said Saraya Abu Bakr al-Sadiq had organised meetings with ISIS representatives, but that they did not reach agreement. ISIS reportedly wanted to claim responsibility for these groups’ operations, a demand the latter refused. Crisis Group interviews, HTS internal security commanders, Idlib, September 2022.

[6] Crisis Group interviews, HTS leaders, Idlib, 2021-2022.

” HTS targeted jihadist groups that refused to bend to its dictates, accusing them of crimes. “

HTS targeted jihadist groups that refused to bend to its dictates, accusing them of crimes. For example, HTS dismantled Firqat al-Ghuraba, led by a French militant with a criminal record in France who goes by the nom de guerre Abu Omar Omsen, who it said had defied the “salvation government”. It held Abu Omar for more than a year, letting him go only when he agreed not to join a militant group in Idlib, recruit French fighters, incite attacks on France or speak to the media.[1]

HTS accelerated its crackdowns on jihadist dissidents in June 2021, when it went after two groups in the Jabal Turkman area. The first, Junoud al-Sham, was led by the Chechen commander Murad Margoshvili, known by the nom de guerre Muslim al-Shishani, whom the U.S. had designated a terrorist group leader in September 2014. HTS accused al-Shishani of sheltering criminals in the group’s ranks and cooperating with another jihadist group on its black list, Jundallah (see below). It gave him an ultimatum: fold his group into HTS or dissolve it.[2] Shishani dismantled Junoud later that year but himself remains in north-western Syria.[3]

In November 2021, HTS launched an attack on Jundallah, led by the Azerbaijani Abu Hanifa al-Adhari, accusing it of extremism (ghulu) and harbouring criminals.[4] It detained all the group’s members, subjecting them to what it describes as an ideological rehabilitation program to wean them off their “hardline” positions, including their belief that they could excommunicate other Muslims.[5] It released twenty of the 50 Syrian Jundallah members it had detained when this program ended, judging that they had changed their views. As a senior HTS figure put it, “The majority of these guys are not ideologues. They are just gullible, blindly following [the group’s founder]. We believe we can convince them of our approach and make them renounce their positions”.[6]

Jihadist groups in Idlib that HTS has not subdued include Ansar al-Islam, which remains one of the few outside its joint operations room. This group seems miniscule, with very little military capability. Without specifying numbers, the main HTS religious scholar, Abd al-Rahim Atoun, suggested that Ansar can man no more than two outposts, implying that it has about 50 fighters.[7]

Meanwhile, several other jihadist and Islamist groups composed mostly of foreign fighters remain in Idlib, untouched by HTS because they abide by its rule. They joined Fatah al-Mubin, where they are organised into five brigades separated by ethnicity or language. One is the Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP), the largest remaining foreign jihadist group in Idlib, which consists mostly of Chinese Uighurs, in addition to a few Syrians. The U.S. and UN listed the TIP as a terrorist group (calling it the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, its original name in Afghanistan before it became the TIP in the late 1990s) in the aftermath of the 11 September 2001 attacks. Washington dropped the designation in October 2020, arguing that the group no longer existed.[8]

The TIP established a Syrian branch in 2012 as a way of reviving itself. It began participating in battles from 2015 onward, claiming to take decisions independently of its Afghanistan-based leadership.[9] It has grown stronger in north-western Syria, where it lives apart from other jihadists and the general population. The group has kept a low profile, though showing consistent support for HTS decisions, which it publishes in regular communiqués. Two communiqués in December 2020 insisted that the group fights for Uighur rights, making no reference to global jihad.[10] Today, the TIP operates as part of the HTS-led joint operations room but says it remains autonomous.[11]

[1] “French jihadist detained in Syria by rival group eyeing ‘sole power broker’ role”, France 24, 4 September 2020. Crisis Group interview, HTS security official, Idlib, October 2022.

[2] Crisis Group interviews, HTS internal security commanders, Idlib, September 2021 and February 2022.

[3] “HTS cracks down on rival groups as northwest pressure builds”, COAR Global, 1 November 2021.

[4] Crisis Group interviews, HTS internal security commanders, Idlib, September 2021 and October 2022.

[5] HTS officials describe these programs as counters to ghulu, which is an Arabic term meaning “excess” or “exaggeration” that many Islamists use to denounce groups they consider more radical than their own. In this instance, it is meant to denote extremism.

[6] Crisis Group interview, senior HTS religious figure, Idlib, February 2022.

[7] Crisis Group interview, Idlib, October 2022.

[8] Sean Roberts, “Why did the United States take China’s word on supposed Uighur terrorists?”, Foreign Policy, 10 November 2020. The TIP’s head in Afghanistan, Abdul-Haq Turkistani, remains listed by the UN for his close association with al-Qaeda and the Taliban. See “Consolidated United Nations Security Council Sanctions List”, UN Security Council, 2 October 2015.

[9] Crisis Group interviews, persons close to the TIP leadership, Istanbul, July 2022.

[10] See the two TIP communiqués, 2 December 2020.

[11] Crisis Group interviews, people close to the TIP leadership, Istanbul, July 2022; Turkish officials, Ankara, October 2022.

” The March 2020 ceasefire … gave HTS room to target non-aligned groups. “

The most troublesome group that HTS has put under its control was Ansar al-Tawhid, a remnant of Jund al-Aqsa, which HTS expelled from Idlib in 2018.[1] Parts of Jund al-Aqsa agreed to leave Idlib, moving to Raqqa, where they joined ISIS.[2] The remainder formed Ansar al-Tawhid in 2018, working with Hurras al-Din when the two groups created Hilf Nusrat al-Islam (Alliance for the Victory of Islam) in April 2018. That October, they joined forces with Jabhat Ansar al-Din and Ansar al-Islam, setting up the Haradh al-Mu’mineen (Inciting the Believers) operations room. HTS decided not to confront this alliance at the time, being preoccupied with offensives by ISIS, on one hand, and the Syrian regime and its allies, on the other. The March 2020 ceasefire then gave HTS room to target non-aligned groups. It forced Ansar al-Tawhid to leave the Haradh al-Mu’mineen operations room that May, a month before dismantling Hurras itself.[3] It then compelled Ansar to select a new leader, Khaled Khattab, whom it could work with. It also forced Ansar to let the HTS security services purge its harder-line elements, whom it then imprisoned.

Ansar al-Tawhid subsequently integrated into the al-Fatah al-Mubin joint operations room, where it complies with HTS policies.[4] Though Ansar is small, HTS sees it as a potent fighting force. More importantly, HTS says it wants to keep small groups like Ansar intact and under control, instead of breaking them up and losing track of their members, some of whom might gravitate toward harder-line groups like ISIS if left on their own.[5] The other foreign jihadist groups that remain in Idlib tend to draw their recruits from particular nationalities. They are marginal entities with very few members. Some occasionally express support for HTS policies, in order to help the group make the case that it is not hounding foreign fighters as such.[6] HTS has folded others as brigades into al-Fatah al-Mubin.[7]

[1] Religious scholars accused Jund al-Aqsa of declaring other insurgent groups non-believers and assassinating their members. HTS first tried to mediate the conflict between Jund al-Aqsa and other groups, before denouncing the former for coordinating with ISIS. See “A warning to Liwa al- Aqsa”, HTS, 19 August 2022 (Arabic).

[2] See “An agreement stipulating the exit of Jund al-Aqsa from Hama and Idlib to Raqqa”, al-Sharq al-Awsat, 17 February 2017 (Arabic).

[3] Ansar al-Tawhid released a statement declaring its independence of all other groups. Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi, “Ansar al-Tawheed statement on independent status: Translation and analysis”, Pundicity (blog), 3 May 2020.

[4] Crisis Group interview, HTS military commander, Idlib, September 2022.

[5] Crisis Group interview, HTS security official, Idlib, September 2022.

[6] See, for instance, two communiqués published by foreigners backing HTS policies and expressing condolences upon the death of an HTS spokesman. “Gratefulness and Support” and “Mourning the death of Abu Khaled al Shami”, 16 August 2022.

[7] These include the Uzbek Tawhid wal-Jihad, which joined al-Fatah al-Mubin, and Katibat al-Imam al-Bukhari, which splintered, with most of its members joining Ahrar al-Sham and a few switching to HTS. HTS folded the Chechen Jaysh al-Muhajireen wal-Ansar and Ajnad al-Qawqaz, as well as the Tajik Jama‘at al-Tajik, the Gulf-based Muhajiri Bilad al-Haramayn, the Iranian Harakat Muhajiri al-Sunna min Iran and the Albanian Jama‘a al-Alban into its military wing. The Moroccan Sham al-Islam integrated into HTS brigades in February 2023. The (Iraqi) Kurdish Ansar al-Islam remains independent. The UN and U.S. sanctioned Katibat al-Imam al-Bukhari as a foreign terrorist organisation in March 2018 and Katibat al-Tawhid wal-Jihad in March 2022, both for cooperating with Jabhat al-Nusra and, by extension, al-Qaeda, despite the fact that Nusra, which later became HTS, had broken from al-Qaeda in 2017. “State Department Terrorist Designation of Katibat al-Imam al-Bukhari”, U.S. State Department, 22 March 2018; “Khatiba Imam al-Bukhari (KIB)”, UN Security Council, 29 March 2018; “Khatiba al-Tawhid wal-Jihad (KTJ)”, UN Security Council, 7 March 2022; and “Designation of Katibat al Tawhid wal Jihad as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist”, U.S. State Department, 6 April 2022.

IV. HTS versus ISIS

While HTS has succeeded in subduing most of the jihadist groups in Idlib, underground ISIS networks pose a challenge of a different order. Resilient in all parts of Syria, the group is able to exploit the lack of cooperation between those trying to fight it and adapt to local conditions to ensure its survival.[1] HTS has a long rivalry with ISIS, which continues today. It has dismantled several ISIS cells in north-western Syria in recent years, but its efforts to completely root out the underground networks have thus far fallen short. In this task, HTS faces military, technical and other obstacles.

[1] See Crisis Group Middle East and North Africa Report N°236, Containing a Resilient ISIS in Central and North-eastern Syria, 18 July 2022.

A. A Fraught History

HTS has been at odds with ISIS for years. Its Syrian founder Abu Muhammad al-Jolani participated as a young man in the post-2003 Iraqi insurgency as a member of what would become the Islamic State of Iraq. In 2011, he worked with that group (soon to rebrand itself as ISIS) to establish Jabhat al-Nusra (which morphed into HTS) in Syria. Jabhat al-Nusra accepted covert financial and logistical assistance from the proto-ISIS group before breaking with its leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in April 2013.[1] By 2014, Nusra was engaged in full-scale hostilities with ISIS, as the two groups fought for control of eastern Syria.[2]

Though Nusra’s leaders kept the group within the jihadist milieu by declaring allegiance to al-Qaeda, their approach diverged sharply from Baghdadi’s. After entering the Syrian conflict in 2011, Nusra won some local sympathy, partly because of its mostly Syrian composition. It kept this support despite its links to Baghdadi’s group, which many saw as foreign and brutal.[3] It also demonstrated responsiveness to local demands, willingness to collaborate with other armed groups that were effective in fighting the Syrian regime and largely refrained from attacks on civilians.

[1] In April 2013, Baghdadi announced a merger of Jabhat al-Nusra and the Islamic State of Iraq into the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) to reassert his control over the group. Jolani rejected the merger by pledging direct allegiance to al-Zawahiri, to whom Baghdadi was theoretically subordinate. Al-Zawahiri intervened, accepted al-Jolani’s loyalty oath and decided that Jabhat al-Nusra would be the al-Qaeda affiliate in Syria, while the Islamic State of Iraq would be the al-Qaeda affiliate in Iraq. Baghdadi in turn ignored this decision and deployed ISIS cells in both Iraq and Syria.

[2] See Hassan Hassan, “The True Origins of ISIS”, The Atlantic, 30 November 2018.

[3] For instance, the Syrian opposition largely denounced the U.S. decision to list Jabhat al-Nusra as a terrorist organisation in December 2012 and held a Friday of protest in support of the group throughout opposition-held areas. Nusra antagonised other opposition groups only when it started to selectively target them after 2014, while continuing to cooperate with other Islamists. “Syrians march in support of Jabhat al-Nusra militants”, France 24, 16 December 2012.

” Many aspects of [Jabhat al-Nusra’s – which morphed into HTS] behaviour were … oppressive. “

That said, many aspects of Nusra’s behaviour were certainly oppressive. Its local courts – some of which other insurgents contributed to running – harshly regulated social life. Without reaching ISIS-level violence, they ordered the closure of entertainment places, imposed observance of prayer and the yearly Ramadan fast, and occasionally executed individuals who had been accused of apostasy, fornication or homosexuality.[1] Along with other groups, Nusra also presented an anti-Alawite discourse that was not dominant when the Syrian uprising began, contributing to the conflict’s gradually deepening sectarian nature.[2]

A deeper fault line between Nusra and ISIS relates to external operations. Nusra – and now HTS – has consistently refused to take part in or endorse jihad beyond Syria, insisting on the primacy of fighting the regime and its backers.[3] In 2012, for example, it reportedly rejected the Islamic State of Iraq’s demand for Nusra to bomb a Syrian opposition gathering in Istanbul.[4]

The rupture came in 2013. At the time, ISIS appeared in Syria, with Baghdadi and his lieutenant Abu Ali al-Anbari trying to gain control of Nusra, drawing many members to their side, especially among the non-Syrian fighters, and proclaiming that the two groups had joined forces under ISIS’s banner. Nusra’s leadership rejected the merger. After a brief period of cohabitation between ISIS and other opposition groups, the dispute escalated into battles that left hundreds dead on both sides. ISIS was forced to leave opposition-held areas. It then declared itself to be the sole caliphate to which all Muslims – including all other insurgents – should pledge allegiance. By 2014, ISIS had driven Nusra out of its eastern strongholds into Idlib and southern Syria.

[1] Some of these rulings can be found in Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi, “Archive of Jabhat al-Nusra Dar al-Qaḍa Documents”, Pundicity (blog), 3 March 2015.

[2] Before the creation of HTS, Jolani propagated an anti-Alawite discourse. In a 2015 interview with Al-Jazeera, he denounced Alawites for supporting the Assad regime, adding that they should amend their religious beliefs. “Abu Muhammad al-Julani reveals Jabhat al-Nusra’s combat strategy in Syria and its stance toward the Alawites and Druze”, Al Jazeera, 27 May 2015 – especially at 11.40 minutes, where Jolani says: “If the Alawis distance themselves from Bashar al-Assad, prevent their men from fighting on his side and renounce the religious beliefs that make them non-Muslims, then they will become our brothers and we will defend them”.

[3] Crisis Group interview, Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, Syria, December 2020. A founding Nusra member confirmed this view. A former adviser to Jolani, he had favoured rapprochement with mainstream Syrian armed opposition groups and resigned from Nusra in 2015. He added that Jolani already had more “moderate” positions early in the conflict, including his acceptance of non-Salafis as members, opposition to sectarian warfare against Shiites and refusal to excommunicate Egyptian President Muhammad al-Morsi, whom most Nusra leaders had called kafir. Crisis Group interview, Antakya, August 2022. The U.S. claims that in 2014 Nusra formed a sub-group, the “Khorasan group”, composed of al-Qaeda veterans, to plan and carry out attacks abroad. The U.S. later decimated this sub-group through drone strikes. Journalists who have interviewed the sub-group’s members claim that al-Qaeda sent it not to plan foreign attacks but to help Nusra survive the split with ISIS by convincing commanders to remain faithful to al-Qaeda. See Dina Temple-Raston, “Al-Qaida reasserts itself with Khorasan group”, NPR, 3 October 2014; and Harald Doornbos and Jenan Moussa, “The greatest divorce in the jihadi world”, Foreign Policy, 18 August 2016.

[4] Crisis Group interview, Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, Syria, December 2020. According to an anti-HTS activist once close to the group, Jolani sent a letter to Baghdadi after the proto-ISIS group entered Syria in 2011, denouncing its sectarian attacks. Aron Lund, “As rifts open up in Syria’s al-Qaeda franchise, secrets spill out”, Carnegie Middle East Center, 10 August 2015.

B. ISIS Returns to Idlib

This fraught history partly explains why HTS has consistently and violently targeted ISIS cells in Idlib. Nusra teamed up with other opposition factions to expel ISIS from Idlib and Latakia in March 2014, after several months of fighting.[1] Yet some ISIS elements remained, taking shelter with relatives and other sympathisers, particularly around Sarmin, Kafr Hind and Jisr al-Shughour. Three subsequent waves of infiltration gave them a big boost.

The first and largest influx occurred in October 2017, when ISIS fighters besieged by regime forces in eastern Hama moved north into HTS-held south-eastern Idlib. The prevailing narrative in Syrian opposition circles is that the regime struck a deal with ISIS, giving safe passage to hundreds of fighters along with their equipment, with the expectation that they would attack other rebels before a regime offensive planned for two weeks later.[2] Most of the fighters did just that, capturing dozens of villages, but other ISIS militants concealed themselves among the masses of civilians fleeing regime bombardment and slipped deeper into Idlib, where they set up covert cells.[3] The ensuing battles in south-eastern Idlib culminated in early February 2018, when ISIS surrendered its last pocket of territory to HTS and other rebels. Preoccupied with the regime offensive slowly rolling back rebel lines, HTS did not track down the ISIS fighters, who remained hidden.[4]

Soon, however, the ISIS elements showed themselves. After the regime ended its offensive, HTS moved to consolidate its control of the north west, pursuing Ahrar al-Sham and its allies for two months.[5] Unknown insurgents, at least some likely belonging to ISIS, took advantage of the fighting between HTS and other rebels to kill at least 33 members of HTS, the TIP, Ahrar al-Sham and other factions in just four days in late April.[6] Suspected ISIS militants also detonated at least two car bombs in the first half of May, one targeting the International Rescue Committee office in al-Dana and the other the Justice Palace in Idlib city.[7]

[1] Alexander Dziadosz, “Al Qaeda splinter group in Syria leaves two provinces – activists”, Reuters, 14 March 2014.

[2] ISIS fighters first emerged in south-eastern Idlib in October, seizing several villages from HTS and triggering months of battles. The Syrian regime then bombed HTS fighters as they attempted to combat ISIS before launching its own ground offensive. See “Violent fighting and fierce clashes at the hometown of the defence minister in Al-Assad’s regime … more that 350 airstrikes … and more than 75 were killed and tens were injured”, Syrian Observatory of Human Rights (SOHR), 28 October 2017; and “After tens of airstrikes … the regime forces penetrate the area of the new birth of the ‘Islamic State’ organization in the east of Hama and clash with Tahrir Al-Sham”, SOHR, 25 October 2017. HTS claims that around 3,000 fighters entered Idlib at this time. Crisis Group interview, HTS security officer, Idlib, September 2021. See also Omar Sabbour, “How the Assad regime has exploited ‘evacuation deals’ to redirect Isis against the rebels”, New Statesman, 18 January 2019.

[3] Crisis Group interviews, HTS security official, Idlib, September 2021 and February 2022.

[4] Walid Al Nofal, Ammar Hamou and Madeline Edwards, “IS forces surrender last pocket of control in eastern Idlib to rebels, opposition spokesmen say”, Syria Direct, 13 February 2018. An HTS security official said ISIS negotiated the surrender with other rebel factions, which guaranteed them release within a few months and promised not to hand them over to HTS. HTS accused the other rebels of allowing some of these prisoners to buy their way out of jail, after which they joined the newly established ISIS cells in Idlib. Crisis Group interview, HTS security official, Idlib, February 2022.

[5] Tamer Osman, “Syrian Islamist factions join forces against Hayat Tahrir al-Sham”, Al-Monitor, 28 February 2018.

[6] “Continuous assassinations claim the lives of 3 persons and raise the number of casualties since the start of the assassinations”, SOHR, 29 April 2018.

[7] “Car bomb hits International Rescue Committee office in northern Idlib as wave of mysterious attacks grows”, Syria Direct, 3 May 2018.

” In May 2018, after winning initial victories over Ahrar al-Sham and its allies, HTS turned to the ISIS threat. “

In May 2018, after winning initial victories over Ahrar al-Sham and its allies, HTS turned to the ISIS threat. With increasing frequency in mid- to late 2018, HTS began raiding ISIS safehouses. To stop the group from recruiting, it published photographs and video footage of its fighters killing or detaining ISIS members. It also staged public executions.[1] While its killings of other militants tapered off, ISIS continued its bombings into early 2019.[2] Fear gripped the governorate.[3]

ISIS got a second boost on 13 March 2019, when Russian jets made thirteen strikes on the outer walls of the main HTS prison, outside Idlib city.[4] As many as 600 prisoners escaped in the ensuing chaos, most of them ISIS members.[5] While HTS claims it recaptured many of the escapees, many others went underground, likely forming additional ISIS cells. HTS security officers say the new cells were concentrated around Kafr Hind, Sarmin and Jisr al-Shughour, all towns where ISIS had enjoyed support in earlier years.[6]

A third cohort of ISIS fighters and commanders entered Idlib one by one from central and north-eastern Syria, in particular after the U.S.-backed, Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces captured the group’s last stronghold in Baghouz, in Deir al-Zor province, in March 2019.[7] Movement on this route appears minimal today. Those who do take it are unable to bring weapons or other supplies with them, since they have to pass as civilians.[8] Nevertheless, HTS continued to mount raids, eventually degrading the ISIS cells’ capabilities. Yet, up to the March 2020 ceasefire, regime offensives in northern Hama, southern Idlib and western Aleppo were triggering mass displacement, which HTS and area residents say ISIS exploited to relocate its cells throughout the governorate, and which shifted HTS resources toward defending the area from regime attack.[9] The ceasefire has frozen the north-western front, allowing HTS to focus on counter-insurgency, but sporadic regime and Russian shelling and bombing continues to uproot area residents. ISIS leaders have mingled with the displaced people in order to find new hideouts in Idlib.[10]

[1] See “HTS executes ISIS members in Idlib city”, Orient News, 2 March 2019.

[2] See chart below showing data compiled from archived HTS media reporting.

[3] An HTS security official justified these methods, citing concerns that the group could have lost Idlib to the combined ISIS and regime offensives. Crisis Group interview, Idlib, September 2022. HTS covered the raids and executions on its Telegram channels and website.

[4] See tweet by Nedal al-Amari, journalist, @nedalalamari, 9:40am, 13 March 2019. It is difficult to track the number of ISIS attacks in Idlib during these years, as, unlike in Turkish-backed rebel areas (such as parts of Aleppo), the group never officially claimed operations. HTS released regular statements on bombings that it pinned on ISIS as well as on its own anti-ISIS raids. Based on this data, ISIS bombings in Idlib appeared to drop off somewhat in late 2018 and early 2019. See Figure 1.

[5] Crisis Group interviews, HTS internal security commanders, Idlib, September 2021 and February 2022.

[6] Crisis Group interviews, HTS internal security commanders, Idlib, September 2021 and February 2022.

[7] Crisis Group interviews, Turkish officials, Ankara, February 2022.

[8] Crisis Group interviews, HTS internal security commanders, Idlib, September 2021 and February 2022.

[9] According to the UN Camp Coordination and Camp Management Cluster, 700,000 people were displaced in north-western Syria in 2018, 1.5 million people in 2019 and 2.1 million in 2020. HTS cites this displacement, which occurred alongside the continual loss of territory, as providing cover for ISIS cells to infiltrate the region from northern Aleppo and Syria’s north east. It says the flight of displaced people also permitted ISIS fighters to move around within Idlib. Crisis Group interviews, HTS internal security commanders and residents, Idlib, September 2021 and February 2022.

[10] Crisis Group interviews, residents, Idlib, February 2022.

C. ISIS’s Idlib Strategy and HTS’s Response

ISIS appears to have altered its strategy in Idlib over the years, as well as its thinking about how the governorate fits into its nationwide plans. During the chaotic 2017-2018 period, it tried to infiltrate Idlib, and then to destabilise it. The subsequent HTS crackdown may have forced the remaining cells to take a less aggressive approach. ISIS was inactive throughout the 2019 regime offensive, knowing that residents would perceive attacks on rebels as de facto support for the regime. Instead, ISIS members laid low in the numerous informal settlements of displaced people, where they allegedly began planning operations outside Idlib.[1]

The under-the-radar ISIS insurgency in Idlib contrasts starkly with the group’s tactics in north-eastern Syria, where it has been able to exploit grievances related to governance failures to recruit, conduct attacks and run extortion rackets. Its activities have dented the Syrian Democratic Forces’ authority in the north east.[2] Comparable efforts in the north west failed to undermine HTS rule as long as the regime was actively trying to retake the area and HTS was fighting back.

ISIS gradually picked up the pace of its campaign in Idlib after the March 2020 ceasefire.[3] Rather than planting bombs, it now staged small arms attacks and went after HTS leaders. These operations tended to be limited, and many went unclaimed.

The ceasefire allowed HTS to meet such operations with a large-scale response, though it took HTS several months to uncover the main ISIS cells. It is difficult to corroborate the group’s claim of a surge in ISIS attacks after the ceasefire, due to the absence of ISIS media reporting from the region. Nonetheless, HTS press releases show sustained anti-ISIS operations from the second half of 2020 through most of 2021, leading to the arrest or killing of scores of ISIS militants. The continued dearth of official ISIS media reports from Idlib, and the absence today of the unclaimed assassinations and bombings that were typical of 2018 and 2019, suggests that HTS’s claims are more than just propaganda.[4] Further underscoring ISIS’s severely weakened position in Idlib is the claim by both HTS internal security officials and Wadah al-Hamawi, the detained founder of Saraya Abu Bakr al-Sadiq, that ISIS cells were requesting materiel from Hurras splinter groups in 2021, and at one point even asked the groups to carry out attacks in ISIS’s name, as the cells were unable to stage operations themselves.[5]

[1] Crisis Group interview, HTS internal security commander, Idlib, February 2022. He said he based his assessment on interrogations of captured ISIS militants.

[2] See Crisis Group Report, Containing a Resilient ISIS in Central and North-eastern Syria, op. cit.

[3] ISIS has not officially claimed any attack in Idlib or northern Hama. Nor has it mentioned either of these regions in its press releases since July 2018, complicating efforts to track its activities there. In contrast, it claimed sixteen attacks on rebel factions in northern Aleppo and Azaz, an area to Idlib’s north east, in 2020, as well as another in 2022.

[4] HTS has published pictures and video footage of at least 21 raids on suspected ISIS militants, as well as twelve on what it calls “criminals” and “regime agents”, since March 2020. The head of HTS internal security said the group has raided many other ISIS cells, for instance capturing several senior commanders in 2021, without publicity. In the evidence it has shown of its operations, HTS has displayed a turn toward professionalism, with its personnel wearing standardised uniforms bearing matching internal security patches, compared to the mixed civilian-military dress they wore previously. The internal security head said the ceasefire had enabled this change. Crisis Group interview, Idlib, February 2022.

[5] Crisis Group interview, senior HTS internal security official, Idlib, September 2022. Hamawi’s statement appeared in the video, “Ghulu: The Poisoned Dagger”, referenced in footnote 41 above.

” HTS concentrated its first counter-ISIS raids in the Sarmin, Kafr Hind and Jisr al-Shughour countryside. “

HTS concentrated its first counter-ISIS raids in the Sarmin, Kafr Hind and Jisr al-Shughour countryside, saying it detained or killed scores of cell members.[1] Support for ISIS in these towns reportedly began to erode as security improved (including through CCTV coverage), along with services like electricity and street lighting.[2] Today, parts of these areas have turned into bustling markets.

HTS has also attempted to undercut ISIS’s appeal by shaping religious discourse, monitoring sermons in mosques and running its own devotional programs. Its senior religious figure, Atoun, and the judges he has trained claim to have given hundreds of speeches and courses since 2013, when the conflict with ISIS first arose, using more pragmatic arguments drawn from Islamic jurisprudence and pointing to ISIS leaders’ excesses to underscore the group’s extremism (ghulu).[3] They aim both to win over low-level ISIS followers and to inoculate the HTS rank and file against ISIS rhetoric. These programs are part of what HTS portrays as larger efforts to control religious discourse, forbidding practices such as takfir (the act of excommunicating other Muslims) or inciting hatred of non-Muslim minorities.[4] HTS recognises that changing ISIS hardliners’ thinking is difficult, but it believes it has managed to spread its own interpretations of Islam – notably including greater acceptance of non-Salafi Muslims and a revived role for the traditional schools of Islamic jurisprudence – among the group’s base.[5]

With its anti-ISIS operations, HTS degraded the group’s ability to maintain cells in the north west, much less conduct complex attacks.[6] In 2022, ISIS may have carried out as few as three attacks in Idlib.[7] On 15 April, a gunman killed a shopper in Idlib city while shouting, “Oh apostates, our caliphate remains”, a common slogan for ISIS since it lost its territory.[8] Circumstances suggest that the attacker may have lacked training and have been remotely directed by ISIS leaders elsewhere.[9] The other suspected ISIS attacks are the murders of two Druze civilians in Jabal Summaq.[10] HTS claims to have apprehended the culprits – Uzbeks whom it alleges were acting on orders from commanders in Afghanistan.[11]

[1] In mid-2020, HTS claimed to have arrested around twenty foreigners whom it alleged were planning attacks in Türkiye and Western countries. Turkish officials say HTS has arrested the last seven men whom ISIS has appointed to head the group’s north-western section. Six of these arrests came in just four months between June and September 2018, coinciding with HTS’s consistent counter-ISIS raids throughout the governorate. Crisis Group interviews, HTS internal security commanders, Idlib, September 2021 and February 2022; and Turkish officials, Ankara, July and October 2022. See also Table 1 in Aaron Zelin, “Jihadi ‘Counterterrorism:’ Hayat Tahrir al-Sham Versus the Islamic State,” Countering Terrorism Center, February 2023.

[2] Crisis Group telephone interviews, activists from Idlib, May 2022; HTS internal security commanders, September 2021; February and September 2022.

[3] Crisis Group interview, Abd al-Rahim Atoun, Idlib, September 2021.

[4] In 2017, HTS issued an order forbidding all its members, commanders and preachers from excommunicating any person or faction, claiming that only its fatwa committee could deliver religious rulings. See HTS communiqué, 12 July 2022.

[5] Crisis Group interview, Abd al-Rahim Atoun, Idlib, February 2022.

[6] By contrast, ISIS officially claimed eleven attacks on rebel factions in Al-Bab and Azaz in northern Aleppo in 2020.

[7] In 2021, an ISIS cell, subsequently rounded up, attacked senior HTS figure Ibrahim Shasho. “In Idlib, a security operation targets ISIS cell”, al-Murasil, 25 February 2021 (Arabic).

[8] See tweet by Abdussamed Dagül, journalist, @AbdussamedDgl1, 6:28am, 13 April 2022. Video footage shows the gunman hiding in a shop doorway as people walk by, a far cry from typical ISIS tactics, in which commandos shoot as many people as possible before detonating an explosives belt, killing still others as well as themselves.

[9] In 2018 and 2019, ISIS cells in Idlib were usually made up of five to ten members – though sometimes as many as 30 – each of whom had designated duties, such as financing, logistics, or creating or obtaining fake IDs. Cell leaders were often Iraqi, while the members were mostly Syrian. The HTS crackdown has reduced the number of these formally structured cells significantly. Crisis Group interviews, HTS internal security commanders, Idlib, September 2021 and February 2022.

[10] See Aymenn Jawad Tamimi, “The life of Turki Bayas of Kaftin in Jabal al-Summaq”, Pundicity (blog), 20 August 2022; and “The life of Hikmat Haddad of Kukku in Jabal al-Summaq”, Pundicity (blog), 1 August 2022.

[11] HTS internal security officials who interrogated the detained Uzbeks said the men were following instructions from Islamic State-Khorasan Province (ISKP) leaders (in Afghanistan), who had told non-Syrian supporters in Idlib to cease attacks on HTS and the Turkish military, so as to focus on killing religious minorities (mirroring an ISKP campaign in Afghanistan). HTS claims that Central Asian ISIS supporters in Idlib began looking to ISKP for guidance after Qardash was killed in February 2022, as they lost trust in the Iraqi-dominated central ISIS leadership and retained ties to Afghanistan through groups like the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, which merged with ISKP in 2015. Crisis Group interview, HTS security officials, Idlib, February 2022. A U.S. security official confirmed the likelihood of connections to Afghanistan, based on trends observed within ISKP. Crisis Group interview, Washington, October 2022.

Gaps in the HTS Strategy for Confronting ISIS

The reduction in attacks supports HTS leaders’ contention that the group has largely destroyed, or driven into hiding, the remnants of the ISIS network that penetrated the region in late 2017. It also points to weaknesses in the ISIS organisation as a whole.

Yet, despite its apparent inability to maintain an operational network in Idlib, ISIS has managed to hide its top leaders among the governorate’s millions of internally displaced people (IDPs). It was an embarrassment for HTS when the first and second self-declared ISIS caliphs – Baghdadi and Qardash – were found in its domain. Whatever success HTS has had in dismantling ISIS cells in Idlib, it has not been able to stamp out the group. Some Western policymakers have speculated that HTS elements may have colluded in sheltering Baghdadi and Qardash, but – given that HTS has hardly shied away from cracking down on ISIS and has shown itself keen to burnish its credentials in doing so – it appears more likely that both men simply evaded detection, exposing holes in the HTS dragnet.[1]

[1] See Vohra, “Rebel-held Syria is the new capital of global terrorism”, op. cit.

” One problem [in countering ISIS] is that HTS must rely entirely on human intelligence in its anti-ISIS efforts. “

One problem is that HTS must rely entirely on human intelligence in its anti-ISIS efforts. “We don’t have the technology or [surveillance] drones, as the [U.S.-led anti-ISIS] coalition does, to listen in and monitor ISIS members”, a security official in Idlib said.[1] ISIS members, furthermore, go to great lengths to avoid alerting HTS to their presence. Many have entered Idlib via the smuggling routes that crisscross Syria, connecting it with Türkiye, Iraq, Lebanon and Jordan. Many more have hidden among the masses of displaced people in Idlib, taking advantage of the constant traffic of goods and people among the region, the Turkish-controlled areas of northern Aleppo and north-eastern Syria to move about.

In these circumstances, HTS authorities are unlikely to learn that ISIS members are in the province unless the latter do something that raises alarm among neighbours, who themselves may be anxious about telling the authorities. Few civilians in Idlib have any sympathy for ISIS, but the fact that so many people in the region are displaced – and often still on the move – means that people often do not know who their neighbours are. That, in turn, makes it difficult to establish robust informant networks. Cells that need to gather weapons and information to prepare for attacks tend to expose themselves. By contrast, the two top ISIS leaders were able to live under the radar for many months, with next to no interaction with the outside world aside from couriers who reportedly delivered messages in person.

[1] Crisis Group interviews, HTS commander, Idlib, September 2021 and February 2022.

E. Displacement and Humanitarian Gaps

The unsolved issue of displaced people benefits ISIS in both north-eastern and north-western Syria, though in distinct ways. While in the north east ISIS exploits informal IDP camps as recruitment grounds, in the north west, it uses them as places for its leadership to hide.

One explanation for the difference lies in living conditions for the displaced, which vary by region. IDP camps are spread throughout the north east. They are mostly administered by international and local NGOs, and the population documented by the UN. Most camp dwellers have lived in the same home for years. Their residences are largely grouped on the basis of place of origin. Thus, while the camps may be outside town, they mimic the social structure of an urban area. People in the camps are susceptible to recruitment by militant groups due to their disenfranchisement, isolation from the permanent residents, and lack of employment and other opportunities. But it would nonetheless be difficult for an ISIS leader to live in a camp undetected.

By contrast, the large displaced population in the north west, while concentrated in a small area, is far more transient. The UN reports that, as of January 2022, Idlib had a population of more than 1.6 million displaced, with another one million displaced in Aleppo, 70 per cent of them in camps, with only 40 per cent of these camps receiving UN support.[1] Some of the camps are akin to established communities, as in the north east. But near daily regime shelling and frequent Russian bombing uproot many people across the governorate time and again.

Hundreds of thousands of people in Idlib are constantly on the move, alighting in shelters on the edges of the established camps. On average, the UN’s Camp Coordination and Camp Management Cluster reports, more than 27,000 people have been displaced in the north west every month since the March 2020 ceasefire came into effect.[2] While regime and Russian attacks fell off somewhat in 2022, reducing the frequency of displacement, some 10,000 people were still being displaced each month. For most, it was not their first such experience. Many do not settle in permanent camps. Some try going back to their homes when the regime’s shelling lets up, only to be displaced again, while many families save up to pay a few months’ rent in a real house before returning to a tent in a new area.[3]

Such was the environment in which ISIS leader Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Quraishi (also known as Abdullah Qardash), his Syrian lieutenant and their two families were hiding. His safehouse, on the outskirts of Atmeh, a town close to the Turkish border, lay near two camps hosting more than 80,000 displaced people. According to the landlord, the house, rented by his Syrian lieutenant, had had 50 different tenants in the two years prior to his arrival in early 2021.[4] When two more families moved in, keeping to themselves and paying month to month, they attracted no particular attention.[5] The area’s high turnover and ragged community fabric worked to Quraishi’s advantage.

[1] “Northwest Syria – Factsheet (as of 31 December 2021)”, OCHA, 2 February 2022.

[2] Data sent to Crisis Group by the cluster, May 2022.

[3] Crisis Group telephone interview, UN official, August 2002.

[4] The landlord and neighbours said Qardash’s lieutenant rented the top two floors, saying he was moving in with his wife and children, as well as his “widowed sister” and her children. Qardash himself was reportedly smuggled into the house several months later. No one ever saw him outside. Crisis Group interviews, Idlib, February 2022.

[5] Crisis Group interviews, residents, Idlib, February 2022.

” Hundreds of wives and children of ISIS fighters, active and deceased, have made their way to Idlib in recent years. “

HTS also cites the influx of ISIS family members released from or smuggled out of SDF detention facilities in north-eastern Syria as a security threat, though so far nothing has occurred to justify the concern. Hundreds of wives and children of ISIS fighters, active and deceased, have made their way to Idlib in recent years. HTS set up a designated area for the newcomers near Darkoush, a town north west of Idlib city. It requires the children to go to school outside the camp where the families live, holding the women in an isolated housing complex known as Jamiliya Camp for a fixed period, before submitting them to what it calls rehabilitation programs. Only after the women complete these programs does HTS allow them to resume something like normal lives.

But HTS still keeps tabs on these women, forcing them to turn to HTS courts if they wish to remarry, and requiring both husband and wife to pass a background check and complete biannual interviews with its security services. It watches the women for lingering loyalty to ISIS, by monitoring if mothers accept NGO aid and allow their children to attend public schools, both of which ISIS doctrine forbids.[1]