Chinese influence in Africa is high on the global agenda, as China within just a few decades has become a key political and economic power in the continent. Indeed, its emergence as a dominant economic and political actor might be the most important development in Africa since the end of the Cold War. This paper analyses China’s economic and political relations with Africa beginning in the 1990s. It argues that the concern is not that China has expanded its economic and political presence in the African continent; rather, that the other stakeholders have ignored it for long.

Introduction

China’s relations with the African continent[a] date back to the 15th century. In the Ming Imperial Tomb in Beijing is a wall painting of a giraffe—it was the famous Chinese admiral and seafarer Zheng He who brought it to the court in Nanjing during one of several expeditions to the Arab world and the east coast of Africa between 1413 and 1419.

In modern times, official relations were established with South Africa after Sun Yat-sen was elected Provisional President of the Young Republic of China in 1911. As the communist leadership consolidated its hold on power in the early 1950s, China launched a more active policy of establishing contacts in Africa. Under the shadow of the Cold War, 29 leaders from political movements in Africa and Asia assembled in Bandung, Indonesia, in April 1955. They discussed peace, economic development, and decolonisation, and agreed to increase cooperation between the peoples of the “third world”, a term coined by China’s then leader Mao Zedong.

Although China at the time was relatively underdeveloped, it provided extensive assistance to emerging African countries. A well-known example from the early 1970s is the Tanzam railway project, which connected the copper belts in Zambia with the port of Dar Es Salaam. This enabled Zambia to export copper without having to pass through South Africa or Rhodesia.

This analysis focuses on the period beginning in the 1990s, when China first pondered a “grander strategy” for Africa. The paper makes an assessment of the implications of increased economic, political and military exchanges between China and Africa.

To be sure, there is no dearth in literature on China’s activities in Africa. Some authors are critical and use the term “neo-colonialism” to describe the relationship. Dan Blumenthal, a US-based expert on China, for instance, has written: ”The Chinese Communist Party’s long-term strategic objective is to displace the United States as the world’s most powerful country and create a new world order favorable to China’s authoritarian brand of politics, or its “socialist market economy.”[1] Others argue that loans and aid from China have an underlying agenda: to make African states dependent on China and make them more compliant in international contexts, where China is dependent on the voices of these states, such as within the UN, or in issues such as Taiwan and Hong Kong. A third group sees China’s operations in Africa as rather favourable, with infrastructure being expanded and modernised.

The rest of the paper attempts to answer the question of whether China-Africa relations have further, strategic objectives, and in particular, if China views its economic relations with Africa as a means for pursuing wider political purposes. The paper outlines the political and normative differences between the West’s[b] and China’s relations with Africa, and gives an account of China’s military and strategic initiatives on the continent. Finally, it asks: How should African states and the wider international community respond to China’s increased presence in Africa?

China’s Economic Relations with Africa

Until the late 1970s the People’s Republic of China’s economic relations with Africa were driven by ideological imperatives. Today, China’s political leadership view economic relations with the continent as a means to achieve the country’s development goals. Within a few decades, China has emerged as Africa’s biggest bilateral trading partner, Africa’s biggest bilateral lender, as well as one of the biggest foreign investors in the continent.[c]

Chinese companies have entered almost all African markets. Today there are more than 1,000 of them operating in Africa; some one million people of Chinese descent reside in the continent.[2] Many of these Chinese companies in Africa are privately owned, while others are wholly or partly state-owned. Within this framework, Chinese companies have great degrees of freedom to operate in Africa on market terms, in addition to being backed by Chinese investment capital on favourable terms.

Trade in goods and services

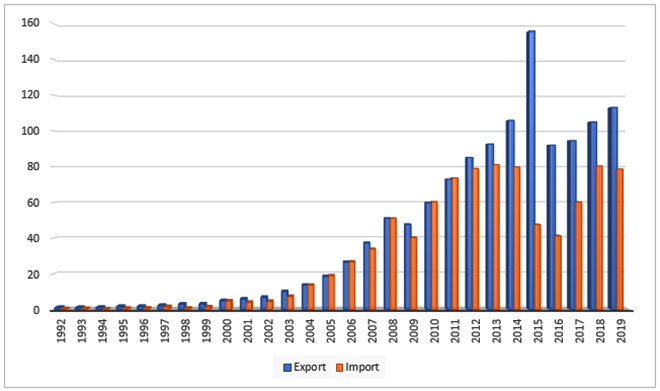

China’s trade with Africa was limited in the 1990s and began increasing substantially around 2005 (see Figure 1). Chinese exports to Africa[3] amounted to USD 113 billion in 2019, while imports from Africa[4] reached USD 78 billion; the volumes have been steadily increasing for the past 16 years. To be sure, weak commodity prices in the period 2014-2017 had a massive impact on the value of African exports to China, even while Chinese exports to Africa remained steady. With a total trade of USD 200 billion in 2019, China is Africa’s biggest bilateral trade partner.

Figure 1. China’s trade in goods and services with Africa (1992-2019, in USD billion, current prices)

In 2019, Chinese exports to North Africa (Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia) amounted to USD 27 billion, or 23.8 percent of the total to the entire continent, while imports from North Africa reached USD 7 billion. More than two-thirds of Chinese trade with Africa thus takes place with the countries located in Sub-Saharan Africa.

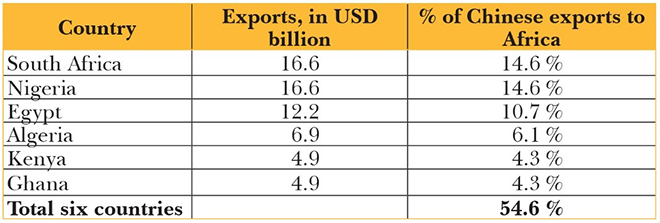

China trades with almost all 53 countries in Africa. Table 1 shows, however, that China’s six biggest export destinations absorb over half of its total exports to the continent. South Africa is China’s principal export market, followed by Nigeria and Egypt.

Table 1. China’s largest export markets in Africa (2019)

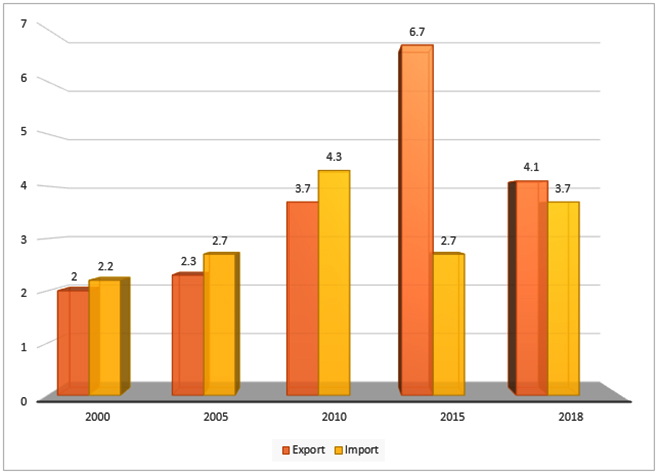

Table 2 shows similar geographical patterns in Chinese imports. Six countries make up 68 percent of total exports, with Angola accounting for almost one-third. From Angola and Libya, China mainly imports oil; from Gabon come oil and manganese. The Republic of Congo mainly provides oil and minerals, and the DRC, cobalt and copper. South Africa mostly exports chemical products, platinum, iron, and steel to China.

Table 2. China’s key import destinations in Africa (2019)

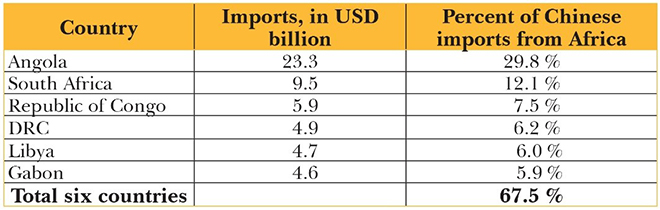

Figure 2 shows that while China´s trade with Africa has increased substantially in absolute numbers, it still amounts to only around four percent of Chinese foreign trade across the globe.

Figure 2. Chinese trade with Africa as percent of China’s foreign trade (2000-2018)

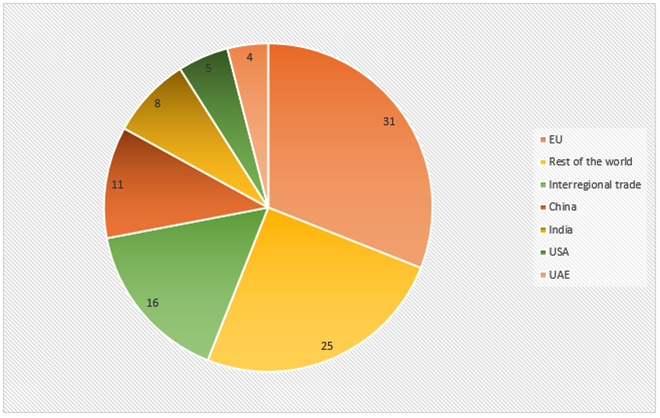

Figure 3. Share in African exports of goods (2019)

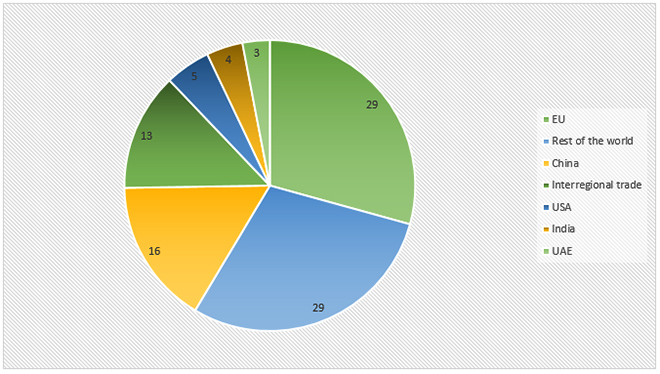

Figure 4. Share in total African imports (2019)

Comparing figures 3 and 4 with figure 2, one can see that from an African perspective, trade with China represents a much higher share of Africa’s foreign trade. Figure 3 shows that China absorbs around 11 percent of Africa’s global export of goods. As a trading bloc, the European Union (EU) is Africa’s biggest export market, making up 31 percent of total African exports; India is the destination for 8 percent of all African exports, the US, 5 percent, and UAE, 4 percent.

Figure 4 shows a similar geographical pattern regarding African imports of goods. While India’s trade with Africa does not match that of China, India has nevertheless established itself as one of Africa’s main bilateral trading partners. For some African countries, trade with China is a cornerstone of the economy. For example, exports to China amount to over 60 percent of total exports for Angola, the Republic of Congo, and Zambia.

Africa accounts for 3 percent of global GDP and global trade. Within the EU, France is Africa’s biggest trading partner. In comparison with China, France’s trade with Africa amounts to 2.5 percent of its global foreign trade, and in the case of UK, the share is 2 percent. While China’s trade with Africa make up a larger share of its total foreign trade than the share for France and UK, these differences are marginal.

Chinese investments in Africa

In 2019, total Chinese Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) to Africa amounted to USD 44 billion, which corresponded to 2 percent of global Chinese FDI. Total FDI from the US to Africa was USD 78 billion, making it the top investor in the continent. American FDI to Africa, however, amounted to only 0.7 percent of its total outward FDI. The UK was the second largest investor to Africa, with USD 65 billion, followed by France with USD 53 billion. For the UK and France, FDI to Africa account for 3 percent of their global investment. Therefore, while Chinese investments have increased over a few years, the totality cannot be said to be extraordinary.

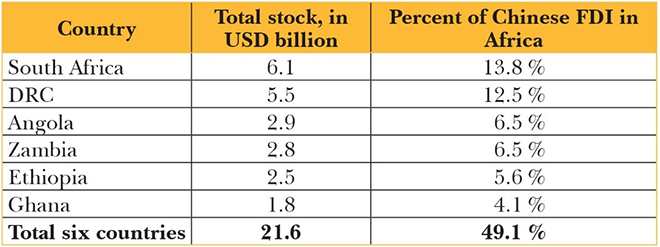

Table 3 shows that in addition to being China’s biggest African trading partner, South Africa is the top destination for Chinese investments, followed by the DRC, Angola, and Zambia. Ethiopia – while potentially rich in geothermal energy and with recent developments in hydropower – is the only country listed in the table that cannot be said to be rich in raw materials. Chinese ventures in Ethiopia are mainly in infrastructure and light manufacturing. Around 30 percent of Chinese FDI in Africa is channelled to infrastructure and construction, while 25 percent goes to mining and extraction of raw materials.

While Chinese FDI to Africa may not seem unusually large, it is worth mentioning that Chinese contract revenues in Africa are substantial. According to data provided by Johns Hopkins University, approximately 30 percent of Chinese overseas construction contract revenue derives from African markets.[11]

In 2019, the gross annual revenues of Chinese companies’ engineering and construction projects in Africa totalled USD 46 billion, dropping by six percent from 2018. About 20 percent is covered by loans from Chinese financiers.[12] 2018 was, however, the fourth consecutive year that gross annual revenues of Chinese companies’ construction projects in Africa declined.

Table 3. Main recipients of Chinese FDI (2019, in USD billion)

Analysis

One can identify three more or less explicitly stated Chinese goals when it comes to economic relations with Africa:[13] access to the continent’s natural resources; export markets for Chinese manufactured goods; and sufficient economic and political stability for China to safeguard its citizens and pursue its economic and commercial interests.

As shown earlier, while China has become Africa’s biggest trade partner, its trade with Africa as a share of total foreign trade is not remarkably bigger than those of other big trade partners with Africa, such as France or UK. It is hardly surprising that China has emerged as Africa´s biggest bilateral trade partner, as it is today the biggest bilateral trade partner for many countries. China’s economic growth has increased its need for raw materials, particularly industrial metals, and fuels. Africa has vast natural resources and, owing to low levels of industrialisation, a huge export potential. China’s economic growth has made it the global industrial hub, and this has been fuelled largely by exports of low-cost manufactured goods. Demand for such products has surged across Africa over the last decades.

China trades with almost all countries in Africa and does not discriminate between regions. On the surface it might seem that China’s economic relations with Africa follow an opportunistic market-based logic. It is partly true, and Chinese corporations operating in Africa are guided by commercial opportunities. However, such an observation does not provide a complete picture. Chinese political decision-makers consider economic relations with Africa as means to satisfy goals for its own economy, and they also facilitate the country’s wider geopolitical aims. This means that commercial relations with some big countries that are rich in raw materials or have other assets that China considers vital—such as Angola and its oil, Zambia and copper, or DRC and cobalt—are buttressed by close political relations that China has ambitiously pursued.

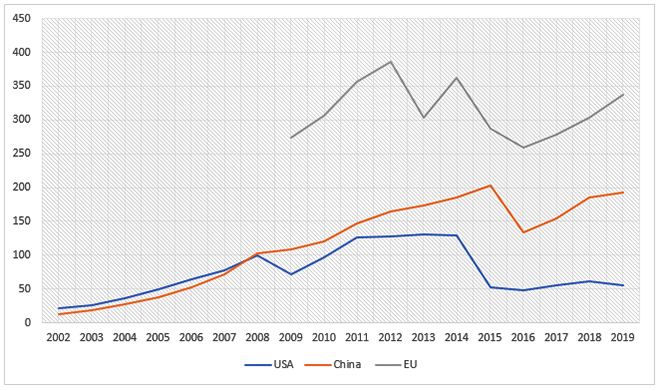

One relevant question is whether Chinese exports and investments grow to the detriment of others. There is little empirical research on this so far, but the data in Figure 5 provides some indications. China surpassed the US as Africa’s top trade partner in 2008. As a trading bloc, EU is a bigger trade partner to Africa than China or the US. Indeed, the trends for American, Chinese and EU-trade with Africa display certain similarities. When Chinese trade with Africa increases, so does African trade with the US or EU. It thus need not be the case that higher levels of Chinese trade with Africa automatically translates to lower levels for the US or EU; it could very well be the reverse. It is not clear from this data whether any substitution occurs.[e]

Figure 5. Africa’s trade with the US, China, and the EU (2002-2019, in USD billion, current prices)

One can identify a number of benefits of increased trade with China for Africa. The emergence of China as an additional trade partner was a key factor behind the high economic growth rates in Africa from the late 1990s to 2014. Higher Chinese demand for African exports improved terms of trade in the continent, providing the countries with additional financial revenues. With China as a new important trading partner, African countries were provided with an additional market for exports and imports. It enabled African nations to diversify foreign trade and become less dependent on trade with the US or EU. Growing trade with China increased Africa’s overall global trade, implying that trade creation outpaced trade diversion.

Both gain, when China provides African countries with capital goods and cheap consumer goods, and African countries supply China with the commodities required to fuel its economic expansion. Moreover, when African consumers are given choices in, for instance, mobile phones, they are empowered.

The other side to trade

At the same time, international trade comes with indirect impacts that provide challenges to African countries that are more difficult to quantify. For example, if Chinese demand for raw materials rises too steeply that it triggers an increase in world market prices, it may bring harm to African nations, such as Morocco or Ethiopia, that are net importers of raw materials.

Furthermore, imports of Chinese manufactured goods can displace local workers and enterprises. In the long run—and this area requires more empirical research—Chinese penetration of African markets could hinder the emergence of a nascent African manufacturing sector. Already, some recent findings indicate that Chinese exports to Africa may be crowding out exports from the more industrialised economies of Africa, notably South Africa.[14] These are, however, still relative declines; the absolute values of South African exports to the continent continues to increase, despite market penetration by China.

It is not surprising that a lot of Chinese investment capital is allocated to infrastructure and extraction of African raw materials. These are areas where Africa has a lot of undercapitalised assets.

African nations have huge investment needs that cannot be met by their small domestic capital markets. Chinese investments provide African nations with modern know-how and technology. Chinese investments in African infrastructure—such as airports, railways, ports, roads, and sewage—increase the overall productive capacity of African economies. At the same time, this may create dependencies with strategic implications.

Chinese FDI in Africa tends to differ from those coming from Europe, Japan, or the US. FDI from these countries is usually carried out by independent profit-maximising private companies; meanwhile, FDI from China is mostly carried out by companies that are dependent on the Chinese state and backed up by cheap Chinese investment capital. This makes it possible for them to have longer time horizons. Furthermore, companies from the West must take into consideration domestic pressure to ensure sustainability, ESG[f] and related factors when they venture abroad. Chinese investors do consider such factors, but find less pressure implementing them. This might give them an “advantage”, if that term maybe used in this context.

One challenge with foreign direct investments allocated to large-scale extractive ventures is that they are capital-intensive but seldom create a lot of jobs for less skilled domestic labour. At the same time, they provide substantial tax revenues. As a result of such dynamics, African elites have generally welcomed Chinese trade and investment, while ordinary Africans sometimes perceive Chinese investments as less benefiting to them.

Focus on Lending

In addition to trade and FDI, loans comprise an increasingly important component of China’s economic relations with Africa.

A decade of rock-bottom interest rates has triggered a global search for yield, yet not enough private capital has been flowing to Africa. African countries often cannot afford to build the infrastructure they need to support their growing populations. Moreover, many of them lack access to international capital markets and banks. In this vacuum, China has emerged as Africa’s largest bilateral lender. Indeed, the Chinese government and its state-owned banks have lent record amounts to governments in low- and middle-income countries since the early 2000s, making China the world’s largest official creditor.

It is estimated that 62 percent of African bilateral debt is owed to Chinese creditors.[15] Research by scholars at the University of Sussex shows that since 2015, China has accounted for 13 percent of bilateral lending to Africa; the next biggest creditor is the US at a much lower 4 percent.[16] According to estimates provided by the SAIS China Africa Research Initiative, Chinese credits to Africa amounted to USD 148 billion in 2019. Of this, USD 44 billion (29.7 percent) is allocated to investments in infrastructure, USD 36 billion to energy, and USD 18 billion to mining and extraction.

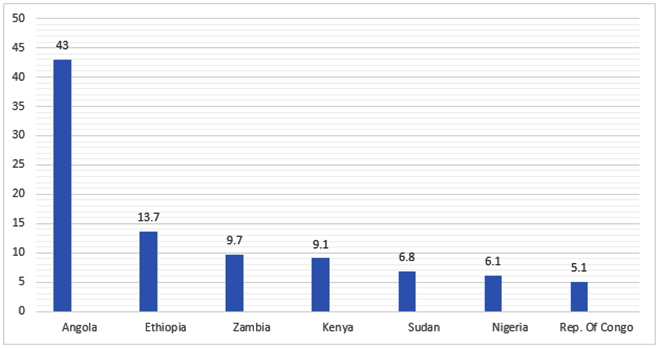

Chinese loans to Africa have helped finance large-scale investments with potentially significant positive effects for growth. At the same time, large lending flows have resulted in the build-up of debt-service burdens. In all, Chinese lending to Africa has covered over 1,000 projects. Figure 6 shows that most of this has accrued to a limited number of countries in the continent, with Angola being by far the biggest debtor. If one looks at the debt burden to China as percent of GDP,[17] Djibouti ranks first with 100 percent of GDP, followed by the Republic of Congo (Brazzaville) (28 percent), Niger (23 percent), Zambia (20 percent), Ethiopia and Zimbabwe (13 percent each) and Angola (12 percent).

Figure 6. Biggest African debtors to China (in USD billion, total stock as per 2019)

While China’s dominant footprint in African trade is well documented, its lending to Africa is less understood.[18] Analysts point out that unlike other major economies, almost all of China’s external lending and portfolio investments are official, meaning that they are undertaken by the Chinese government, state-owned companies, or state-owned banks. [19] Two banks dominated Chinese overseas lending: the Chinese Export-Import Bank and the China Development Bank (CDB). The same study further underlines that China does not fully disclose its official international lending and there is limited standardised data on Chinese overseas stocks and flows.[20] Adding to such paucity, commercial providers such as Bloomberg or Thomson Reuters do not keep track of China’s overseas loans. It is therefore difficult to obtain precise information about not only the magnitude of Chinese lending to Africa, but also the rates of interest and terms of maturity, and the kind of collaterals involved. The situation is thus such that most of China’s bilateral lending is carried out by so-called policy banks and state-owned commercial banks, which may be controlled by the Chinese state, but operate as legally independent entities, not as sovereign lenders.

A 2021 research paper by Anna Gelpern, professor of Law at Georgetown University, has analysed the structure of Chinese loans to Africa and other developing nations.[21] The authors find that overall, China is a muscular and commercially-savvy lender to developing countries. Chinese contracts contain more elaborate repayment safeguards than their peers in the official credit market, alongside elements that give Chinese lenders an advantage over other creditors. At the same time, many of the terms and conditions the authors of this present paper reviewed, exhibit a difference in degree, not in kind, from commercial and other official bilateral lenders.

According to Gelpern, Chinese contracts contain confidentiality clauses that bar borrowers from revealing the terms or even the existence of the debt. Second, Chinese lenders seek advantage over other creditors by using collateral arrangements such as lender-controlled revenue accounts, and committing to keep the debt out of collective restructuring (“no Paris Club” clauses[g]). Third, cancellation, acceleration, and stabilisation clauses in Chinese contracts potentially allow the lenders to influence debtors’ domestic and foreign policies.

Unlike the members of the Paris Club of the biggest sovereign creditors, Chinese loans often require collateral for development loans. Since Chinese loans are backed by collateral, they often enjoy a high degree of seniority. If an African country wants to apply for debt relief, its Chinese creditors can claim the rights to assets held in escrow. This is another possible inroad for China to claim assets in African countries, often mentioned by critics that claim that the country has “neo-colonial” ambitions and methods.

When a country’s debt service burden is not transparent, debt sustainability analyses are hampered. For private investors this makes asset pricing difficult. Furthermore, a lack of transparency may be an obstacle to crisis resolution, since information on the size and composition of a country’s debt is essential to assure fair burden sharing and orderly crisis management. Chinese banks often tend to renegotiate sovereign loans bilaterally and without transparency.

This is among the reasons why Chinese lending to Africa has been the subject of debate and controversy. Some have suggested that Beijing is deliberately pursuing “debt trap diplomacy,” imposing harsh terms on its government counterparties and writing contracts that allow it to seize strategic assets when debtor countries run into financial problems. Others argue, meanwhile, for the benefits of China’s lending and suggest that concerns about harsh terms and a loss of sovereignty are greatly exaggerated. Still others suggest that the debate is largely based on conjecture, as neither policymakers nor scholars know if Chinese loan contracts would help or hobble borrowers as few independent observers have seen them. They argue that existing research and policy debate rests upon anecdotal accounts in media reports, cherry-picked cases, and isolated excerpts from a small number of contracts.[22]

If there is anything that is more certain, it is that Chinese lenders are willing to extend loans to poor African countries without demanding much in terms of governance reforms and anti-corruption measures. The result has been projects that are bound by draconian lending conditions, are expensive to operate, and unlikely ever to produce decent returns.

Over the years, China has embarked on a massive lending spree to developing countries, mainly as a way of promoting its flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The BRI, however, has faced growing criticism for flaws such as lending to low-income countries with unstable finances, lack of transparency, and not considering social and environmental impact studies on the projects they are financing. Bearing in mind that many developing nations, in Africa and in other parts of the world, have become heavily indebted because of the Covid-19 pandemic, China as creditor may have to confront a situation where several of its foreign borrowers will have difficulties living up to contractual undertakings. This could lead to a situation where future Chinese international lending will be more risk-averse and restrictive.

Chinese foreign lending to developing countries already seems to have been reduced in the last few years. From a record figure of USD 75 billion in 2016, Chinese lending in 2019 shrunk to USD 4 billion.[23] Such a massive decline cannot be explained only by a general global economic downturn; it is most certain that this is due to specifically Chinese circumstances.

Future Chinese investments abroad will likely apply far more stringent criteria on the commercial viability of projects. In the past, a substantial proportion of Chinese foreign investment had been more about using financial resources to extend the country’s political influence. Putting its reputation on the line for the BRI, China will likely put more emphasis on commercial gains from its future investments. It is reasonable to assume that, in the future, China will no longer be as big of a lender to Africa. As African nations will continue to have substantial needs for foreign capital, reduced Chinese lending could open possibilities for others, such as the European Union and India.

Over the past decade, many African nations have accumulated higher debt-burdens. Each country profile is unique and a lot of this began before China became a big lender. Debt relief for African countries is becoming an important topic on the international agenda. Being a large creditor, China will have a significant role in the process. While China does not participate in the Paris Club—used by Western governments to negotiate sovereign debt relief—Chinese creditors have restructured loans in the past and appear willing to renegotiate arrangements and allow borrowers to defer payments. Chinese creditors, however, prefer such negotiations to take place on a strictly bilateral basis.

China as a Political Factor in Africa

The Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) held its first ministerial conference in Beijing in October 2000. The forum’s objectives include the promotion of political cooperation, and creating a favourable environment for China-Africa business and trade. Other commitments from China are providing special funds to support well-established Chinese enterprises to invest in African countries, to cancel debts, send extra medical teams, and develop student exchanges.[24]

However, the literature on China’s political activities in Africa often mention other goals, which are considered to guide the Chinese government.[25] One such example is to diplomatically isolate the democratic Republic of China (Taiwan) by persuading African countries to sever diplomatic relations with this nation. Another is to influence attitudes towards Hong Kong. These are examples of China’s underlying goals in cooperating with African countries, which would aim to achieve compliance with China’s further geopolitical aspirations.

The question has been raised as to whether China, as part of its efforts to achieve these official and unofficial goals, wants to export a specific Chinese model for development, which can be replicated in other countries, in this case, those in Africa. Current research points in different directions here, and many believe that this should be studied primarily in relation to the African political elites who are regularly invited to China and courted by Chinese diplomats and businesses.[26]

A well-known Chinese political scientist, Zhang Weiwei, has argued that the specific developments that have taken place in China over the past 40 years are not transferable to other countries. In the book The China Wave: Rise of a Civilizational State, published in 2011, Weiwei highlights eight different factors that contribute to China being a unique civilisational state. The first are the four “superfactors”: a super-large population; a super-large territory; a super-long tradition; and a super-rich culture. Then follow the four “unique factors”: a unique language; unique politics; a unique society; and a unique economy.

This interpretation of China’s uniqueness undoubtedly displays a level of pride and self-confidence in relation to one’s own culture. It is not unlike imperialist Europe during the latter part of the 19th century, with its self-image of being the most developed part of the world and carrying the responsibility to civilise the rest.

About the Communist Party, Weiwei says:

The Chinese Communist Party (CPC) is not a party as the term “party” is understood in the West. At its core, the CPC continues a long tradition of a unifying Confucian ruling entity, which represents or seeks to represent the interests of the whole of society, rather than a Western political party that openly represents certain group interests. [27]To the extent that this view is shared among the leading political classes in China, it could explain why the country today, unlike the Soviet Union during the Cold War, does not actively incite revolutionary movements that aim to install Marxism-Leninism in “third world” countries. Such activism would also not be in line with Chinese business interests, as these operate predominantly within the Western capitalist logic and the framework of the World Trade Organization (WTO). It would also run counter to China’s official policy of non-interference in the affairs of other countries.

On the other hand, China seems to have a clear will to influence political leaders in Africa and other developing countries, regardless of whether or not it involves copying its own development model. The authoritarian interpretation of the CPC has also gained ground, since Xi Jinping in 2018 received a de facto indefinite mandate as president.

China’s principle of non-interference in the domestic affairs of other countries has met with some criticism, as it can be argued that it risks weakening the principle of “Responsibility to Protect” or R2P adopted by the United Nations (UN) in 2005—with the support of China. The purpose of R2P was to give the international community a greater opportunity to intervene to protect civilian populations from genocide, ethnic cleansing, war crimes, and other crimes against humanity. This principle is seen as a tool to prevent these abuses from being committed, and also to provide a basis for a mandate to intervene, if the preventive work fails.

Arthur Waldron, professor of International Relations at the University of Pennsylvania, believes that the notion of a Chinese policy in Africa based on non-interference in the affairs of other countries needs to be dissected and argues that the Chinese have had few qualms about interfering if judged to be in their own interest.[28] According to Waldron, China’s interpretation of the non-interference policy is that foreign policy should not be enslaved by abstract principles but rather guided by pragmatic considerations.

Such policy seems to have the support of Africa’s elites. From the West’s viewpoint, it has been argued that this gives China an advantage in business relations with African countries, as the political elites there prefer loans, aid and business agreements from a great power that does not demand certain liberal rights, corruption-free governance, sustainability, transparency, nor democracy. Others argue that these trends are exaggerated, mainly because there is no single model for development that China seeks to promote.[29] Still others claim that engagement with China tends to lead countries in a less democratic direction.[30] At the same time, the West has in several occasions favoured non-democratic regimes as long as they have worked for other normative goals that were in line with the West’s development agenda—such as poverty reduction, and improved healthcare and education.[31] Moreover, it has been done when the West saw a need for access to crucial raw materials, or a “buffer” vis-à-vis political enemies or possible military bases.

Normative similarities and differences

The political scientist Stein Ringen has characterised China as a “sophisticated dictatorship”, one that stands between the authoritarian model and the totalitarian one—or a “controlocracy”.[32] There are mock trials and sudden disappearances, of which the entrepreneur Jack Ma is one of the latest high-profile people to have been affected, just like in Stalin’s Soviet Union or Hitler’s Germany.

Ringen discusses what motivates the dictatorial power of the Chinese Communist Party, or its raison d´être. He considers the constant rise in the material standard of living and the eradication of poverty as the main legitimising factor after Deng Xiaoping’s takeover. At the end of 2020, China declared that it had completely eradicated extreme poverty in the country over an eight-year period.[33] President Xi Jinping emphasised at an official ceremony in Beijing in February 2021 that this “miracle is a complete victory that will go down in history.”[34]

At the same time, this shows that China has achieved goals 1 and 2 of the UN Agenda 2030—i.e., no poverty or hunger—for a massive one-fifth of the world’s population. This, together with the continued and accelerating economic exchange between the West and China, means that in terms of material goals such as prosperity and poverty reduction, standards between West and China are running in parallel. Furthermore, these material objectives are in line with officially stated development and poverty reduction policies in most African countries.

There may be another factor that motivates the power of the Communist Party. China experts point out that there are “three ghosts” chasing China’s political leadership: the century of humiliation of 1842 – 1949, when foreign powers ruled the “Middle Kingdom”; the destructive excesses of violence during the Mao Zedong era; and the fall of the Soviet Union. Another way of expressing this is the fear of weakening or undermining the peace-making Leviathan, the central power. Unfortunately, this also tends to favour authoritarian leadership and the incumbent regime. At the same time, peace and stability remain fundamental values.

As discussed briefly earlier, China in Africa often acts bilaterally. Although there is a common forum for contacts with Africa through the FOCAC and other arenas, agreements are mostly bilateral. When China acts in African countries, it often does so outside the various platforms for development established by other donors, where common normative requirements for issues like procurement and sustainability are monitored. China often abstains from such cooperation.

In the tourism sector, for example, there are Chinese entrepreneurs that act outside the organisations that exist for ecotourism and for sustainability requirements—this despite China’s high-profile assurances at world summits as being “protectors” of climate agreements and sustainability goals. Thus, in terms of common demands for sustainable development, anti-corruption and common social rights requirements within donor organisations, there is no normative agreement between the West and China in Africa.

Meritocracy is a traditionally strong value in China.[35] The administrative apparatus has historically been built on a Confucian basis. From the 17th century it included a rigorous countrywide system for screening prospective civil servants every three years, which remained in various forms until 1962.[36] After the chaos of the Cultural Revolution and Deng Xiaoping’s return to power, one of the first steps he took was to reintroduce national examinations as a basis for admission to higher education.

Meritocracy in this sense is largely in line with norms in the West, but not insofar as it provides a basis for recruitment to political leadership within the Communist Party. It is hardly possible to claim that recruitment to the political classes in the West or in Africa today takes place on strictly meritocratic grounds. Nevertheless, the lack of transparency in China’s political system creates opportunities for corruption, which undermines the meritocratic norm.

In China, land cannot be owned by private individuals. However, there are possession rights that can be valid for up to 70 years. Since 2015, registers for possession rights have been established in municipalities.[37] In addition, individuals can own real estate, but not the land they stand upon. In Africa, Western countries and NGOs have initiated formalisation of property rights in several countries. In this there is no normative agreement with China.

In recent years, the Communist Party has further tightened its grip on the educational sector by forcing private schools to hand over ownership to the state without compensation.[38] Together with other recent moves, this puts China’s governance system closer to the totalitarian model, based upon a Leninist power structure and with the Communist Party and the president as the main players. Thus there is, using Ringen’s framework, a strong tendency towards “controlocracy”. It is not likely that this will result in the promotion of liberal democracy, division of powers, and the rule of law as governance models when engaging with African countries.

China’s Diplomatic Offensive

The FOCAC has been active for many years and provides political and diplomatic backing for Chinese companies and investments in the continent.

A 2020 analysis of China’s active diplomacy to influence African leaders, military, and senior officials observes: [39]

Beijing’s investment in professional training for senior cadres from African countries means that three synergistic goals can be achieved: (1) the dissemination of a Chinese model for development and governance (2) the development of a professional network involving Chinese senior officials, politicians and specialists counterparts in various African countries and other developing countries within the BRIC, as well as (3) a socialization of African senior officials and politicians into China’s views on Chinese culture, Chinese diplomacy and interpretations of history.Another aspect of China’s “charm offensive” is the so-called Covid vaccine diplomacy. Donations of relatively modest doses of Chinese vaccine make headlines in African newspapers, while the West is perceived to be prioritising its own citizens.

An example of Chinese diplomacy in Africa is an official visit by Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi to the Seychelles that took place on 31 January 2021. He underlined that China’s diplomacy has always been based on equality between small and large countries. China advocates multilateralism, he said, and opposes power politics; it supports “democracy in international relations” and supports the UN in its legitimate role in international relations. Large countries should be the first to follow the basic norms that govern international relations, Wang Yi emphasised, adding that they should also be the first to “follow the principle of non-interference in other countries’ internal relations.” They should also be the first to shoulder their international commitments on climate change and sustainable development.[40]

One aspect of the “propaganda war” is China’s growing media presence. From ownership of local radio stations to the establishment of a China Central Television station in Nairobi, Kenya, China is becoming a major influence in the daily discourses in these countries.[41] According to Afrobarometer survey data in 36 African countries, 23 percent believe that China is the most influential foreign power in their country, close behind “the former colonial power” (28 percent) and slightly ahead of the US (22 percent).[42]

Cultural factors and attitudes

A report from the Afrobarometer research project in 2016 states that the US development model is preferred by most Africans, while a majority view the Chinese presence in Africa favourably.[43]

A drawback is that Chinese business people have been accused of being condescending towards Black Africans. In part, this can be attributed to the idea of cultural superiority, as suggested by the notion of what Weiwei referred to as the four Chinese “superfactors” and the four “unique” Chinese factors, discussed in an earlier section of this paper.

In Kenya, a Chinese restaurant owner was arrested in 2015 after denying Black Africans entry.[44] Sometime in the same year, a Chinese businessman was expelled after calling a Kenyan employee and the country’s president “baboons”. The 26-year-old employee said he had not encountered outright racism until the incident.[45] The Chinese embassy apologised, saying that this did not represent the attitude of the Chinese people.

Zambia has had several incidents of unfair labour practice, some involving violence. During a 2010 strike over working conditions in a Chinese-owned coal mine in the south of the country, two Chinese managers opened fire and 11 workers were seriously injured. The two were brought to justice, but the indictment was later dropped.[46] In 2012, a Chinese foreman was murdered at the same mine.[47]

In 2020, three Chinese supervisors at a textile department store in Lusaka in Zambia were murdered and their corpses burned, after they were accused of keeping Black workers locked in a container to avoid being infected by Covid-19, while Chinese customers were allowed to move freely within the premises. The press said that “the waves of racial antagonism went high.”[48] A few weeks earlier, a restaurant and a hair salon that had barred Zambians were ordered closed by authorities.[49]

Such tensions have been exploited by the country’s political leaders. In 2007, the then opposition leader Michael Sata issued a statement saying, “We want the Chinese to leave the continent and the former colonial powers to return. Of course, they also exploited our raw materials, but at least they took care of us.”[50] Sata won the 2011 presidential election in a high-profile anti-China campaign. Conversely, the government of Edward Lungu (president, 2015-2021) leaned heavily towards China, which also is the country’s single largest lender.

The Western response

Signs are emerging that the West and its allies, such as Japan and India, are aiming to counter the economic and diplomatic initiatives from China. One example is the EllaLink, a transatlantic optic data cable launched with funding from the European Investment Bank and others. The aim is to be an alternative to the BRI, and to boost high-quality projects in middle- and low-income countries, including Africa.[51] In 2021 the EU and India launched a global infrastructure partnership, although both sides are careful not to brand it as any sort of anti-Beijing alliance.[52] The India Africa Trade Council, inaugurated in January 2021, is yet another example: it aims to open 13 trade offices in each of India’s major cities, assisting businesses that could be interested in conducting trade with African countries.

China’s Strategic and Military Interests in Africa

Economic globalisation has meant that Chinese business interests also benefit from long-term economic rules and the prevention of conflicts and wars. Thus, in 2008, Chinese warships arrived on the coast of Africa in the Indian Ocean, to take part in international operations against piracy, as those activities have also affected Chinese ships. It was the first time China’s navy operated in these waters since the 15th century.

Soon it was clear, however, that the Chinese presence was not aimed at only fighting pirate attacks. When piracy subsided around 2012, the Chinese warships remained, and China declared that its naval presence is part of an ambition to protect its economic interests in the Middle East, North Africa, and East Africa. It can also be seen as part of the “Maritime Silk Road”, a major infrastructure project proposed by President Xi Jinping in 2013, which would primarily involve Chinese investment in ports.[53] The Chinese naval presence was further expanded by a naval base in Djibouti. On 1 August 2017, the 90th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Liberation Army, the base was inaugurated. It is the country’s first naval military base outside China, and is leased for ten years, for which China pays USD 20 million annually.

China’s military presence in Africa goes back to the 1970s, when it supported guerrilla groups such as Unita in Angola and Frelimo in Mozambique with financing, weapons, and logistics. Today, China sells weapons to many countries in the region and offers training for African officer aspirants.[54] There are extensive contacts between China’s military leaders and their African counterparts. For one, China is training on-site African armies, police forces and soldiers involved in multilateral peacekeeping operations. China also provides financial support to the African Union’s military operations, conducts military exercises with African countries, and plays an active role in UN peacekeeping operations in the continent.

At the same time, the United States, like erstwhile colonial powers such as Britain and France, have extensive military cooperation in the continent going far back in time. France is estimated to house about 9,000 people in its military operations, mainly in West Africa and the Sahel. The UK has significantly fewer permanent staff but trains up to 10,000 each year in Kenya through a mutual defence cooperation agreement. The United States is considered to hold about 7,200 personnel in the continent, but this commitment will face cutbacks in the coming years. The Chinese naval force in Djibouti is today estimated to comprise 300 military personnel and 1,700 civilians.[55]

Russia has also expanded its presence in Africa in recent years, through the training of military personnel and arms exports to some 20 countries. Japan, for its part, opened a military base in Djibouti in 2011, with the aim of protecting shipping and raw material supplies, but also in view of supporting access to African markets and balancing the presence of China.[56] Turkey and the United Arab Emirates have also expanded their military activities in recent years but have no fixed bases.

Since 1989, about 40,000 Chinese soldiers have been involved in a total of 24 UN peacekeeping operations in Africa. Today, about 2,400 Chinese soldiers participate in seven of these operations. In 2019, China contributed USD 7 billion to the UN peacekeeping forces, equivalent to 15 percent of the UN budget.[57] Among the permanent members of the Security Council, China today contributes the largest contingent of personnel in UN peacekeeping operations.[58]

Over the years, China has signed bilateral agreements on arms deliveries to Namibia, Botswana, Angola, Sudan, Eritrea, Zimbabwe, and Sierra Leone, among others. Helicopters have been delivered to Ghana, Mali, and Angola, as well as tanks to Zimbabwe. In Sudan and Zimbabwe, the Chinese military has had factories to produce small arms.[59]

In 2014, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army conducted its first joint military exercise with an African country in Tanzania. In 2018, units from the Chinese Navy visited naval bases in Cameroon, Gabon, Ghana, and Nigeria and conducted bilateral exercises there.

The Horn of Africa consists of Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti, and Somalia. With the completion of the Suez Canal in 1896, the area became an important transit route for international trade, by significantly shortening the transport routes for trade between Asia and Europe. It is through the Horn of Africa that Africa is linked to the Arab world. Djibouti has become something of a commercial hub, where ships from all corners of the world reload goods and refuel their ships. Important commercial transit routes run outside the Horn of Africa, and the area is close to current conflict areas such as Yemen. Even before the civil war broke out in the region, it had undergone extensive militarisation. France, Italy, Egypt, Israel, the United States, Japan, Germany, and Spain are a selection of countries with a military presence in the area.

China’s military presence in Djibouti has several purposes. Owing to its military presence there, China can take part in military operations to combat terrorism and protect Chinese ships from piracy.

During the conflict in Libya in 2011, the Chinese military evacuated 35,000 Chinese citizens stranded in the country. From Djibouti, in 2015, the Chinese military was able to evacuate 800 Chinese from the civil war in Yemen. In view of its major economic interests in Africa, it is inevitable that China will take an active interest in dealing with the continent’s political emergencies. An important purpose of the military presence is to protect Chinese factories, transport routes, and personnel in Africa. Another purpose is to use military hardware as a means of projecting Chinese soft power.

Through large-scale economic and personnel engagement in the UN’s military operations, China hopes to be seen as a responsible actor for maintaining order in the region. In times when other countries have reduced such support, China’s increased involvement has mainly been viewed positively in Africa. Of course, the continent also offers an arena where China is given the opportunity to test weapons systems and other military skills. By nurturing ties with military leaders in African countries, China seeks to incorporate Africa into the country’s wider geopolitical strategy. China has long been a key political and economic player in Africa; in recent years, it has become a significant military player.

Conclusion

How should other stakeholders interpret China’s increased activity in Africa?

First, it should be said that this is a matter for the states and people of Africa. Africans rightly react negatively when representatives of world powers mostly regard the continent as an arena for their own strategic or economic interests, as was largely the case during the Cold War.

Second, there are few obstacles for other countries to go on a diplomatic offensive in Africa, should they so decide. The concern is not that China has an increased economic and political presence in Africa, but that others have ignored it for long. The surrounding world, i.e., the EU and US, does not seem to have a strategy for how to face the Chinese offensive or to increase its own presence and confidence in Africa.

Some initiatives are emerging to give alternatives to the Chinese economic offensive, involving the EU, US, Japan, and India. It would be wise to consider reducing the bureaucracy and the lists of requirements surrounding such investments, to be able to act in a more pragmatic way without giving up the most fundamental values.

Third, African countries should be wary of becoming heavily indebted to China. They must consider the involved political risks of dependency.

Fourth, the EU, US and allies should work more systematically and consistently to incorporate China into common diplomatic, commercial and NGO forums in African countries, where mutually beneficial norms and practical solutions can be identified.

Although Africa still makes up a small part of the world economy, population forecasts by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) show that in 20 years, sub-Saharan Africa will have more people of working age than the rest of the world. Over the next 40 years, one billion potential consumers and producers will be added to the region. With better institutions and greater investment in human capital, Africa can add considerable dynamism to the world and the world economy. The future of this continent may well hold important tipping points for the world’s development, including climate change and terrorism.

Geopolitical tensions between China on the one hand, and the West and its allies on the other, have increased, but Africa is hardly the primary arena for this. The world community should be alert to any signs of antagonistic or expansionist ambitions that China may have in the continent. It would be wise for African countries as well as for the West and its allies to prepare for how such developments should be handled.