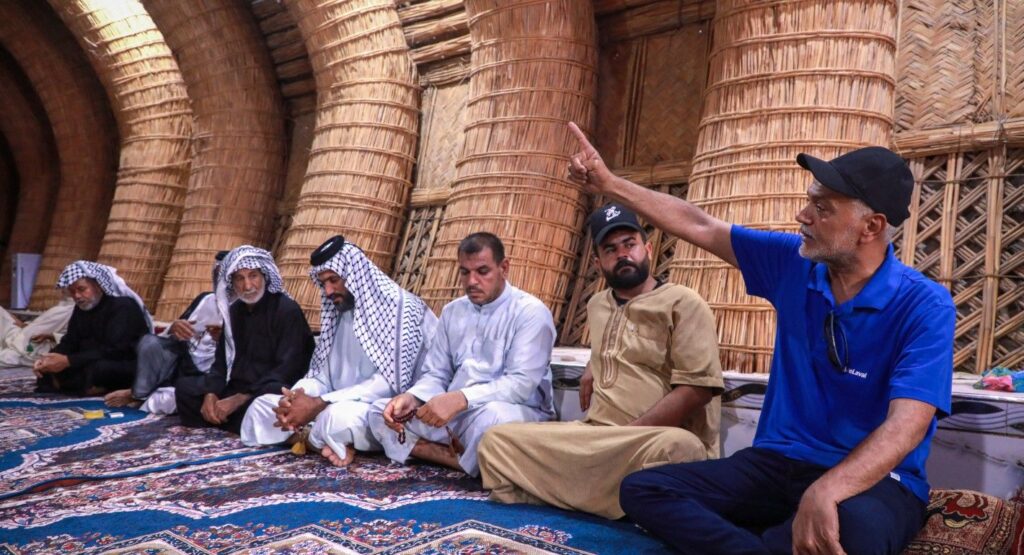

A Real Estate Empire Built on Dark Money

Since 2012, hundreds of millions of dollars from Kyrgyzstan — one of the poorest countries on earth — have poured into bank accounts in Europe, the United States, and the Middle East on behalf of a single family.

Much of that money ended up in an expansive real estate portfolio that stretches from the Persian Gulf to the shores of California.