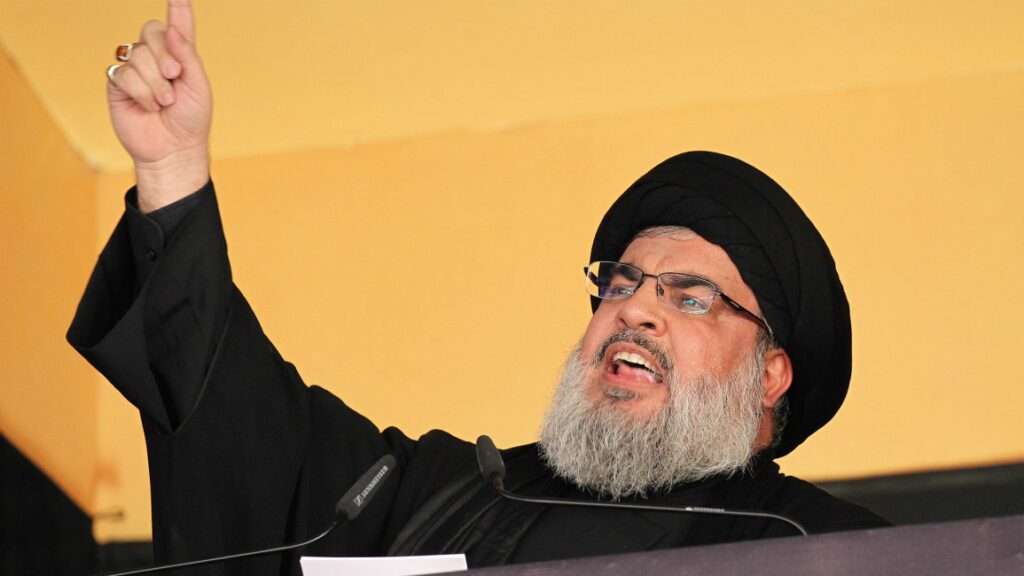

Regional politicians, others react to killing of Hezbollah’s Nasrallah

IRAN’S FOREIGN MINISTRY: The ministry said in a statement that Nasrallah’s “path will continue and his goal will be realised in Jerusalem’s liberation”.

Following are reactions by regional politicians and others to the killing of Hezbollah leader Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah in an Israeli airstrike in Beirut on Friday: