Anti corruption protests in Tripoli and Misurata

Hundreds of protesters gathered on Sunday evening at the Martyrs Square in Tripoli, to protest the endemic corruption in the state, demanding accountability and the dismissal of those responsible.

Hundreds of protesters gathered on Sunday evening at the Martyrs Square in Tripoli, to protest the endemic corruption in the state, demanding accountability and the dismissal of those responsible.

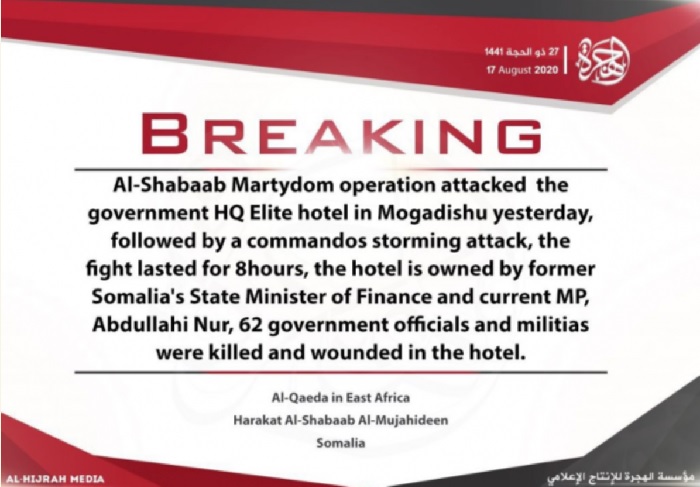

Al Shabaab stormed the Elite Hotel in Lido Beach after breaching the hotel’s gates with an explosive-laden vehicle. At least four gunmen, plus the suicide bomber driver, were involved in the attack which killed nearly 20 people and injured another 43. A five-hour siege ended with assailants killed.The owner of the hotel, former Finance Minister, Abdullahi Mohamed Nur, was inside the hotel during the attack as well as other government employees. Al Shabaab often chooses soft targets like restaurants and hotels to attack government employees and policy makers. At the beginning of August, an al Shabaab suicide bomber targeted another seaside restaurant hosting government officials at Lul Yemeny Seaside Restaurant. A nearly identical attack to the Elite Hotel attack tactics occurred the week prior when al Shabaab suicide bomber targeted 12th April Somalian Army Brigade in the Wardighley District of Mogadishu.Via al-Andalus media, al Shabaab claimed credit for the attack, “Al-Shabaab forces waged amaliyat against a hotel owned by member of federal parliament.”

A military coup in Mali to oust the country’s political leadership has raised prospects of spiraling instability that could result in an opportunity for jihadist groups.

Over the past two days, Shabaab, al-Qaeda’s branch in East Africa, has launched two suicide assaults across Somalia. The first targeted a popular hotel in Mogadishu, while the second hit a Somali military base outside of Baidoa.

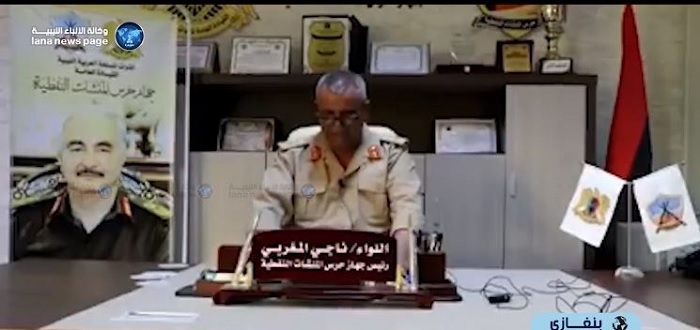

The head of the eastern-based and Khalifa Hafter-aligned Petroleum Facilities Guards (PFG), Naji Moghrabi, announced in a televised address yesterday that they are lifting the blockade on the export of oil and gas already produced and in storage.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM), and UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, said they were deeply saddened by the tragic death of at least 45 illegal immigrants and refugees on August 17 in what they had described as the largest recorded shipwreck off the Libyan coast this year.

Libyan Army Spokesman, Colonel Muhammad Gununu has cast into doubt the effectiveness of the new ceasefire announced in the country on Friday.

Chairman of Presidential Council, Fayez Sarraj, has given orders for the Libyan army forces under the Government of National Accord to implement an immediate ceasefire and end all hostilities in Libya.

A patrol of the Anti-Smuggling and Infiltration Unit of Zuwara has rescued 24 migrants off the coast of the city.

The spokesman for the Libyan Government of National Accord’s (GNA) Sirte-Jufra Operations Room Abdelhadi Drah said they had depicted six flights on Russian military cargo planes coming from Syria’s Lattakia to eastern Libya’s Labreg and Benina airports.