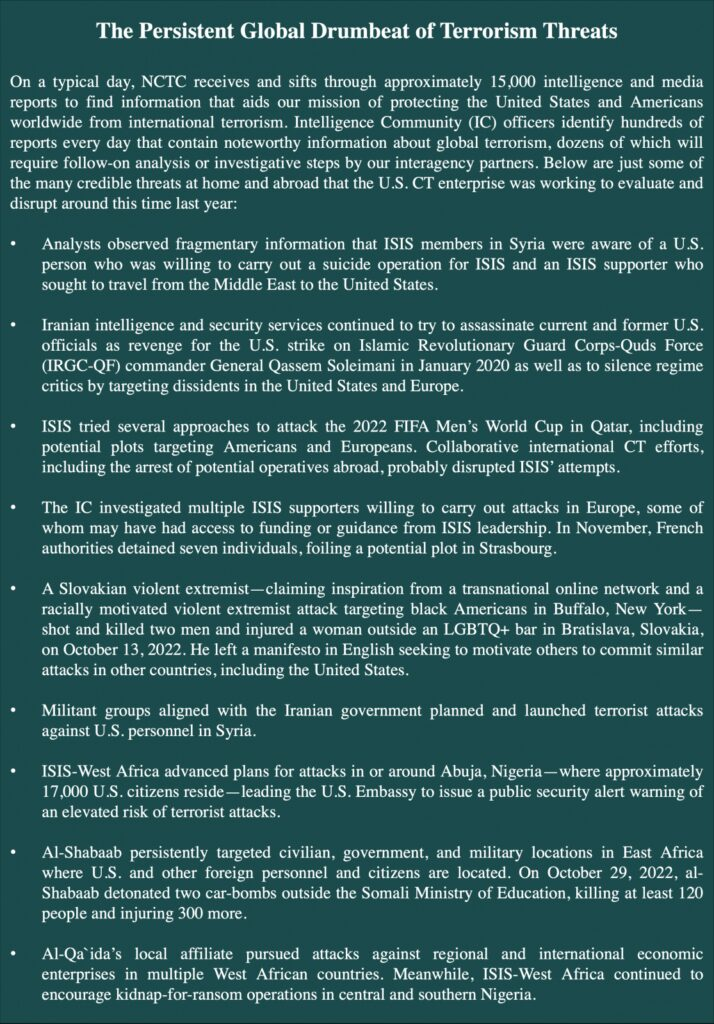

Abstract: Terrorism may no longer be at the top of most Americans’ minds, but the U.S. counterterrorism (CT) community remains dedicated to protecting the United States, our people, and our allies from terrorist violence. To succeed in this still-critical mission, our CT practitioners will need to retain the agility, expertise, and tools to detect, warn of, and disrupt global terrorist threats as terrorist tactics and tradecraft evolve. Our CT architecture will need to remain nimble enough to quickly identify new threats and overcome enduring challenges that might allow space for terrorists to advance attacks.

Foreign terrorist groups generally have less capability to orchestrate mass casualty attacks in the United States than at any time since September 11, 2001, because of the efforts of the United States and our partners to create and maintain an adaptive and effective counterterrorism (CT) enterprise. The U.S. government has painstakingly developed its ability to detect and disrupt plots at early stages, suppress the capabilities of terrorist networks, and deter or thwart potential attacks through defensive security measures, while safeguarding the privacy and civil liberties of the American people. Nevertheless, many terrorist adversaries still have the ability to inflict devastating human and economic costs. The CT enterprise is dedicated to preventing that harm from materializing and keeping the nation’s focus on other national security priorities. In this article, we aim to share details of what the overarching picture looks like by providing NCTC’s assessment of the current terrorism threat and highlighting key challenges for shaping a sustainable and nimble CT architecture going forward in a period of more constrained resources.a

The Evolving International Terrorism Landscape

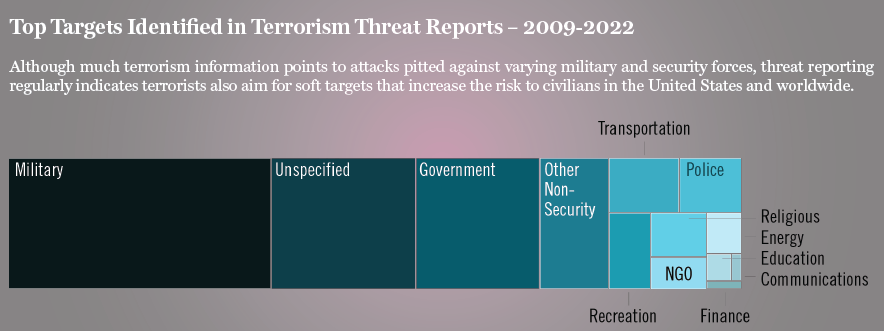

When explaining the general state of the international terrorism threat, regardless of classification level or audience, we often highlight four broad themes that characterize our leading CT challenges: regional expansion of global terrorist networks alongside degradation of their most externally focused elements; the growing danger from state involvement with terrorism; the reality that lone actors are the most likely to succeed in carrying out terrorist attacks; and the risks posed by terrorist innovation.

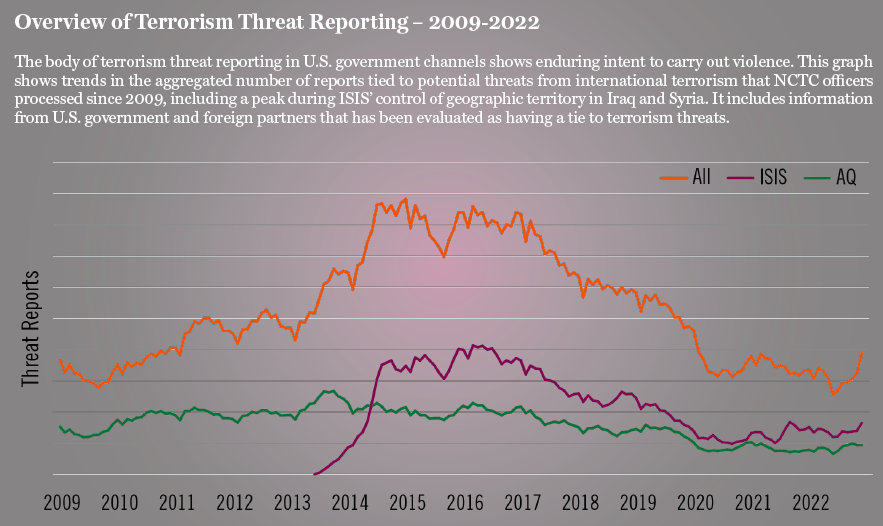

Regional Expansion Amid Degraded External Threats: Probably most notable—and a change steadily achieved over the past two decades—is that the United States is safer because the overall threat from foreign terrorist groups is at a low point with the suppression of the most dangerous elements of Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham’s (ISIS’) and al-Qa`ida’s global networks. Thanks in large part to U.S. and regional partner CT operations, both organizations have suffered significant losses of key personnel, and sustained CT pressure is constraining their efforts to rebuild in historic operating areas.

These losses have been partially offset by an increased threat from ISIS-Khorasan in Afghanistan—which has become more intent on supporting external plots—and the expansion of ISIS and al-Qaida networks across Africa. ISIS-Khorasan’s increased external focus is probably the most concerning development. However, the branch has so far primarily relied on inexperienced operatives in Europe to try to advance attacks in its name and, in Afghanistan, Taliban operations have for now prevented the branch from seizing territory that it could use to draw in and train foreign recruits for more sophisticated attacks. Al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), despite its own losses of key personnel and resources, probably remains al-Qaida’s most dedicated driver of external plotting. Remaining senior members of the Yemen-based group continue to produce media reinforcing cohesion of al-Qaida’s global network as well as calls for attacks against U.S. interests globally.

More Aggressive State Involvement with Terrorist Activity: We anticipate that rising global strategic competition will lead to increased state support to terrorist actors as a foreign and security policy tool. The end of the Cold War, the subsequent rise of a U.S.-centered global order, and the forceful U.S.-led global response to al-Qa`ida’s attacks of September 11, 2001, helped suppress the kinds of state support for terrorism seen in the 1970s and 1980s. Yet, the increasingly brazen and persistent activity of the Iranian government during the past four years, including support for terrorist operations inside the United States, exemplifies the spectrum of challenges still posed by state support to terrorism. Iranian intelligence and security services—which have pursued several dozen lethal plots and assassinated at least 20 opponents across four continents since 1979—are advancing plotting against the United States, other Western interests, and Iranian dissidents more aggressively than they have at any time since the 1980s.

The Iranian government has become increasingly explicit in its threats to carry out retaliatory attacks for the death of IRGC-QF Commander Qassem Soleimani in 2020. Iranian officials have created lists of dozens of current and former U.S. officials that it blames, including as primary targets a series of former senior U.S. government officials it holds primarily responsible for Soleimani’s death.

Militant groups aligned with the Iranian government periodically conduct rocket and unmanned aircraft system (UAS) attacks against U.S. facilities in Syria and have threatened to resume more complex or frequent attacks in Iraq. From 2003 to 2011, the Iranian government and Lebanese Hezbollah supplied explosively formed projectiles that killed 196 U.S. personnel in Iraq and wounded 861. The potential threat posed by the provision of more lethal and sophisticated capabilities by the Iranian government remains a serious concern for U.S. personnel in the Middle East.

The Enduring Challenge of Extremist Violence by Lone Actors: Violent extremists who are not members of terrorist groups remain the most likely to successfully carry out attacks in the United States, and we expect this trend to persist for the next several years. Plotting by these individuals—typically lone actors—is often difficult to detect and disrupt because of the individualized nature of the radicalization process and use of simple attack methods. Since 2010, violent extremists influenced by or in contact with ISIS, al-Qa`ida, and other foreign terrorist organizations have conducted 40 attacks in the United States that have killed nearly 100 and injured more than 500 people.

Racially or ethnically motivated violent extremists (RMVEs) who have a transnational influence or connectivity also pose a sustained threat of violence to the U.S. public. These RMVEs have conducted some of the gravest acts of mass violence in years, including the shooting that targeted black Americans at a supermarket in Buffalo, New York, last year and the attack at a Walmart in El Paso, Texas, in 2019 that targeted immigrant populations. The Buffalo shooter highlights the transnational nature of the RMVE threat. The attacker—who killed 10 and injured three—acted alone but clearly took inspiration from the manifestos and social media posts of past influential RMVE attackers and plotters abroad, particularly the Norwegian attacker in 2011 and the Australian attacker in New Zealand in 2019. These foreign RMVEs have been particularly influential for likeminded individuals globally, with at least six subsequent RMVE attackers worldwide claiming inspiration from the writings of the Norwegian attacker and at least four citing the Australian attacker, including his use of social media to livestream his violence.b These attackers are part of an international ecosystem of individuals who share violent extremist messaging, mutual grievances, manifestos of successful attackers, and encouragement for lone actor violence.

Emerging Technologies and Terrorist Innovation: Although most terrorist attacks continue to use long-available methods, many of the most dangerous terrorist plots have sought to exploit novel tactics and new technologies. Commercially available technology has dramatically improved terrorist groups’ ability to communicate securely, recruit privately, and conduct surprise attacks. Terrorists across the globe, including those in remote areas, are now able to obtain and use technology such as UAS for attacks or 3D printers for weapons manufacturing. We are also concerned about shifts in tactics such as increased terrorist targeting of critical infrastructure.c And we remain alert for indications that malign actors are using emerging platforms, such as virtual or extended reality, to broaden their violent extremist networks and conduct training or advances in generative artificial intelligence to enhance propaganda campaigns and potentially boost technical expertise.

A Nimble Global CT Architecture Is Key to Success

In 2023, U.S. CT efforts benefit from more than 20 years spent building a multi-layered CT architecture including law enforcement, military action, screening capabilities, and CT partnerships. This system is suppressing the threat of large-scale terrorist attacks against U.S. interests at home and abroad through strong collaboration with state and local colleagues, with the private sector, and with allies and other partners around the world. In recent years, we have seen terrorist groups advance fewer sophisticated plots, as compared to disruptions in previous decades of multiple innovative efforts by ISIS and al-Qa`ida such as to bypass aviation security measures by hiding explosives in personal electronic devices, in larger shipped or checked devices to mask screening, or developing plots using non-metallic bombs.

A sample of the actions taken to mitigate the threats from late 2022 highlighted at the beginning of this article demonstrates the broad range of tools that the United States and our partners have developed to detect and disrupt plots, degrade terrorist group capabilities, and enable defenses to deter or thwart attacks. Prioritizing public safety, the U.S. government shared intelligence leads with domestic and international law enforcement to enable the arrest and prosecution of likely terrorist operatives. Where law enforcement was not an option, the IC informed potential military operations to mitigate threats. We identified previously unknown terrorists and their associates in part by developing new connections within our intelligence holdings and ensured this information fed into the U.S. government’s screening systems. The United States issued public and private statements informing those at risk to take precautions, possibly deterring some would-be attackers. Our response to all of these involved focused intelligence collection and cooperation across the U.S. CT enterprise as well as with foreign partners.

Law Enforcement and Civil Justice: The value of legal interventions including arrests, prosecutions, and sanctions as an integral part of collaboration across the CT enterprise—including federal, state, local, and international agencies—is highlighted by the detection, exposure, and disruption of plotting during the last two years by a range of terrorist adversaries. In July, arrests by German and Dutch authorities disrupted an ISIS fundraising network connected to the group’s branch in Afghanistan that was seeking weapons for attacks in Germany. In January, U.S. federal prosecutors charged three Iran-connected members of an eastern European criminal organization for plotting to murder an Iranian-American journalist based in New York. In August 2022, the Department of Justice announced charges against an IRGC member for offering to pay a confidential human source $300,000 to kill a former U.S. National Security Advisor in the United States. And, in May 2022, cooperation between U.S. and European law enforcement agencies led to the arrest of a Slovakian RMVE for his involvement in terrorist activities.

Military Action: Looking more broadly, terrorist networks are weakened by the removals of key figures from the battlefield that often happen as a result of military operations. This includes the loss of leaders who drive the intent of organizations to pursue external operations as well as individuals with operational and specialized expertise who have advanced innovative plots. ISIS has lost three overall leaders and at least 13 other senior figures in Iraq and Syria since early 2022—including two in April who had been planning attacks in Europe or other locations—contributing to a loss of expertise and a decline in ISIS attacks in the Middle East. Additionally, al-Qa`ida has suffered significant setbacks in recent years in Yemen, Syria, and South Asia, including the death of its leader Ayman al-Zawahiri in a U.S. airstrike in 2022. The detention of high-value terrorist prisoners has also reduced threats to U.S. interests, but we are also mindful that some figures—absent successful disengagement programs—could still rekindle that danger should they be released or escape from confinement.

Short-term effects of leadership removals are most evident, but consistent pressure has always been required to degrade terrorist capability over the longer term. Without this, terrorist groups can reconstitute in their historical strongholds or expand in other locations where they can draw on local conflict or militant elements to gain a foothold. Half of ISIS’ branches are now active in insurgencies across Africa where they already pose a local threat to U.S. persons and facilities and may be poised for further expansion. Captured enemy material collected by U.S. forces during a January 2023 operation in northern Somalia that killed a key ISIS financial facilitator reinforces that networks in Africa have the potential to fund and help lead ISIS’ global enterprise. Africa is also al-Qaida’s most promising area of growth. Al-Shabaab is now al-Qaida’s largest, wealthiest, and most lethal affiliate, while Jama‘at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin increasingly threatens attacks in urban areas of West Africa and has used ransoms of international hostages to help fund the network.

Screening and Vetting Capabilities: The U.S. government’s multi-layered CT infrastructure also relies on a robust screening system that protects the nation by using the information and knowledge we have developed to track the movements of terrorist plotters and prevent their entry into the United States. For example, NCTC maintains the Terrorist Identities Datamart Environment (TIDE), which is the U.S. government’s central and shared repository of information on known or suspected international terrorists and international terror groups. Our screening and vetting support efforts in collaboration with partners such as DHS, FBI, and the Department of State (DOS) make it more difficult for actors with ill intent to receive visas, board international flights, or cross borders. NCTC reviews about 30 million new travel and immigration applications annually—in addition to about 120 million continuous reviews—to enable DHS and DOS to prevent terrorist travel to the United States.

CT Partnerships and Information Sharing: Success in disrupting threats and degrading terrorist networks depends on international CT cooperation now more than ever. Deepening our relationships with longstanding partners while developing new CT partnerships will give us insight in places that no single country can develop on its own. We must track plot details over extended periods—sometimes spanning months or years—to understand terrorists’ evolving actions. Cases such as the 2019 arrest of Kenyan national Cholo Abdi Abdullah, who was charged with conspiring to provide material support to a designated foreign terrorist organization, prove the point. U.S. intelligence and law enforcement entities in collaboration with Philippine and Kenyan authorities uncovered information that a senior al-Shabaab leader in 2016 had directed Abdullah to obtain pilot training in preparation for a terrorist attack, according to the now-public U.S. District Court indictment.d Obscuring those terrorist ties, Abdullah traveled from Africa to the Philippines, enrolled in flight school, and took pilot training during 2017-2019. While earning his pilot’s license, Abdullah also conducted research on the means and methods to hijack a commercial airliner, gathered information on the tallest building in a major U.S. city, and searched for how to obtain a U.S. visa. Persistent CT tracking and partnerships brought together the disparate pieces of information to thwart a potentially catastrophic attack.

CT efforts to degrade the media output and appeal of terrorist groups, coupled with public and private measures to limit their ability to exploit popular online platforms, have contributed to decreases in attacks inspired by foreign terrorist organizations. There were two such attacks and roughly a dozen foiled plots in the United States in 2022, reflecting a decline since 2015 and the height of ISIS’ English-language messaging efforts. Even as technology companies improve their capabilities to detect and respond to violent content online, terrorists find new methods to spread their message, underscoring the persisting challenge. For example, a tech platform removed the livestream of the May 2022 Buffalo attack within two minutes after the violence began—the fastest livestream removal to date—and yet, original and altered video clips were still widely shared by users globally on other platforms that are less able or inclined to take action.

In the area of CT finance, we remain focused on terrorists’ methods for raising, moving, storing, and spending their funds. Since 2015, we have noted increased sophistication in the methods terrorist groups are using, particularly the adoption of cryptocurrencies. Identifying terrorist support networks and highlighting key facilitators is paramount to stemming group expansion and external attack plotting. To accomplish this mission, we analyze data from a variety of sources to discover networks, identify new trends and emerging technologies being used in terrorism financing for senior decisionmakers, as well as highlight potential disruption and investigative opportunities for our partners.

Keeping Sufficient CT Pieces on the Global Terrorism Chess Board

Maintaining our high performance in a period of decreasing resources as other national security priorities take center stage requires prudent effort. We must retain a nimble and flexible CT enterprise that is able to detect threats in real time, interpret what is happening, and then position our pieces to counter or proactively prevent our opponents’ moves. In many ways, that combination of strategic planning and tactical detail is similar to engaging in multiple chess games, where understanding your opponents’ intentions requires a keen focus on how each move may signal developing threats. The CT enterprise must cultivate complementary capabilities that can maintain our defenses while still being agile enough to introduce new ways to thwart terrorists.

Maintaining Strong Opening Strategies: Our gains—wins big and small to curtail violence and remove key players from the battlefield—are impressive yet fragile. To mount our strongest possible offense, we must maximize use of all of the international terrorism information available from technical, geospatial, and human sources while also continuing to evaluate the best ways to fill information gaps by better exploiting other data already in U.S. government holdings. This rigorous exploitation furthers our collective ability to share intelligence leads with mission partners, advances international CT investigations and operations, drives new intelligence collection, and informs strategic analysis for policymakers. And better knowing what we have positions us to develop the next-generation collection capabilities—enabling us to better anticipate and thwart future changes in terrorist plotting.

Ensuring Our Pieces Can Work Together: Because terrorist threats morph, we must regularly evaluate how our understanding of terrorist behaviors and networks matches the global terrorism landscape. CT watchers must be alert for when terrorists alter their tactics and explore new paths—such as using technology in novel ways—to try to gain an advantage. Capitalizing on the need for a flexible, learning posture is at the heart of how the U.S. government has succeeded in actively suppressing an evolving terrorist threat by institutionalizing information sharing, collaboration, and innovation by a diverse workforce from across federal, state, and local partners. And we will build the CT workforce of the future by continuing to enhance our cadre’s technical and analytic skills to keep pace with the terrorism landscape.

Learning from Others: Tapping into global CT expertise is a critical part of remaining vigilant. Success in disrupting threats and degrading terrorist networks often relies on CT partnerships at home and abroad. As new social constructs, platforms, and data emerge, we strengthen our understanding by building ties to outside partners. Although maintaining connections with foreign governments will always be important, terrorism containment over the longer term will benefit from deeper awareness of and connections to private sector companies and outside researchers whose CT work supplements the government’s efforts. Building relationships with private sector companies whose hardware or online platforms may be used by terrorists to advance violent aims can help us understand and predict the most important factors at the core of the terrorist-counterterrorist match-up.

Anticipating Adversaries’ Possible Moves: CT practitioners must chase leads until we know which are real, often against threats that persist over years. As we survey the ebbs and flows in terrorism worldwide, we must also be mindful of how changes in the information we are using—including in volume and type—affects our analytic assessments and operational decision-making. Shifts in our information on terrorist actors changes our ability to evaluate threats and identify opportunities to deter terrorist actions, and we must be mindful of how those gains and losses change our assessment of the threat.

Conclusion

Our successes against terrorism are not a done deal. We are proud that today’s environment presents fewer large-scale, transnational terrorism plots than we faced in the recent past because of the active and ongoing efforts of the U.S. government and our global partners to detect, disrupt, deter, and defend against threats. We recognize that we must remain agile and attentive against the diverse challenges posed by global terrorist networks, state involvement with terrorism, lone or loosely connected violent extremists, and terrorist innovation. In an era of more constrained resources, we must thoughtfully nurture our capabilities to gather, exploit, and inform on terrorism developments to enable the best whole-of-government CT action. Our mission to protect the U.S. homeland also serves to ensure that the strategic surprise of terrorist violence does not again dominate our national security agenda and divert our focus from other national priorities. CTC

Substantive Notes

[a] NCTC serves as the primary U.S. government organization for analyzing and integrating all intelligence possessed or acquired by the U.S. government pertaining to international terrorism and counterterrorism. NCTC also provides support to the Department of Justice, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Department of Homeland Security as the lead U.S. government agencies for assessments on domestic terrorism. NCTC focuses its support on understanding connections to international, including transnational terrorism, and defers to these Departments on purely domestic terrorism matters. This article highlights information and data from a range of U.S. government-collected sources that report on international terrorism, including publicly available sources. NCTC analysts applied qualitative and quantitative analytic methods to develop the judgments explored in this assessment.

[b] RMVE attacker manifestos have provided RMVEs globally with a common set of foundational documents for reference and have championed the idea that only violence can prevent the death or marginalization of the white race or Western Christians. To understand that reach, NCTC completed comparative qualitative and quantitative analysis on the manifestos of RMVE attackers who committed violence in multiple countries since 2011. We found common core narratives and a range of thematic content that we assess helps sustain the transnational RMVE movement as they circulate online.

[c] Authorities have disrupted several violent extremist plots against power grids in Western countries since 2020. Terrorists and militants overseas have maintained high rates of attacks targeting electricity infrastructure. Meanwhile, attacks against electric power substations in the United States have also increased substantially since 2017, according to Department of Energy data, including several unattributed incidents that led to power outages. We are working with federal, state, local, and industry partners to help them prepare for such threats.

[d] The activity is presented here as alleged in the indictment in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York case, United States v. Cholo Abdullah. For additional details, please see this indictment unsealed by the U.S. Department of Justice on December 16, 2020.