Introduction

Regaining the tribal loyalty lost in the first years of the Syrian Revolution was an inevitable step in the regime’s eastern offensives. During the first half of the war, managing the weakened and fractured tribes, particularly in Deir ez-Zor, seemed to be a low priority. However, the rise of ISIS in central Syria in 2014 proved an opportunity for Damascus, eliminating “third way” options and forcing tribesmen to choose between Bashar al-Assad and ISIS. This led to the first large movement of opposition tribal factions back to Assad’s camp. By the time Damascus launched its 2017 central Syria campaign, the regime’s intelligence agencies had successfully re-integrated significant portions of tribes from Homs, Raqqa, and Deir ez-Zor, forming loyalist militias under the command of long-loyal tribal leaders.

When the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) prepared to enter the Arab-majority regions of Raqqa and Deir ez-Zor, it employed a similar strategy. It attempted to appease the tribes by including them in the Deir ez-Zor Military Council and promising political equality. However, the SDF and Democratic Union Party (PYD)-led governing body, the Autonomous Administration in North and East Syria (AANES), immediately faced resentment from tribal figures over allegations of corruption in the allocation of oil revenue, the imposition of mandatory military service, and arrests of Arab civilians.1 Though the SDF has kept an open line of communication with tribal leaders and stepped up anti-ISIS operations in the region, it has failed to fully address the aforementioned issues, implement political reform, and provide an adequate level of security to appease tribal leaders.

Amid the increase in ISIS attacks, the SDF also faces the dual task of expanding its presence in the Arab-majority province while maintaining a facade of local empowerment. Yet, due to the refusal of the SDF’s allies, the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS, to deal directly with tribal figures, it remains the only force capable of aiding the tribes in their struggle for security in the region.

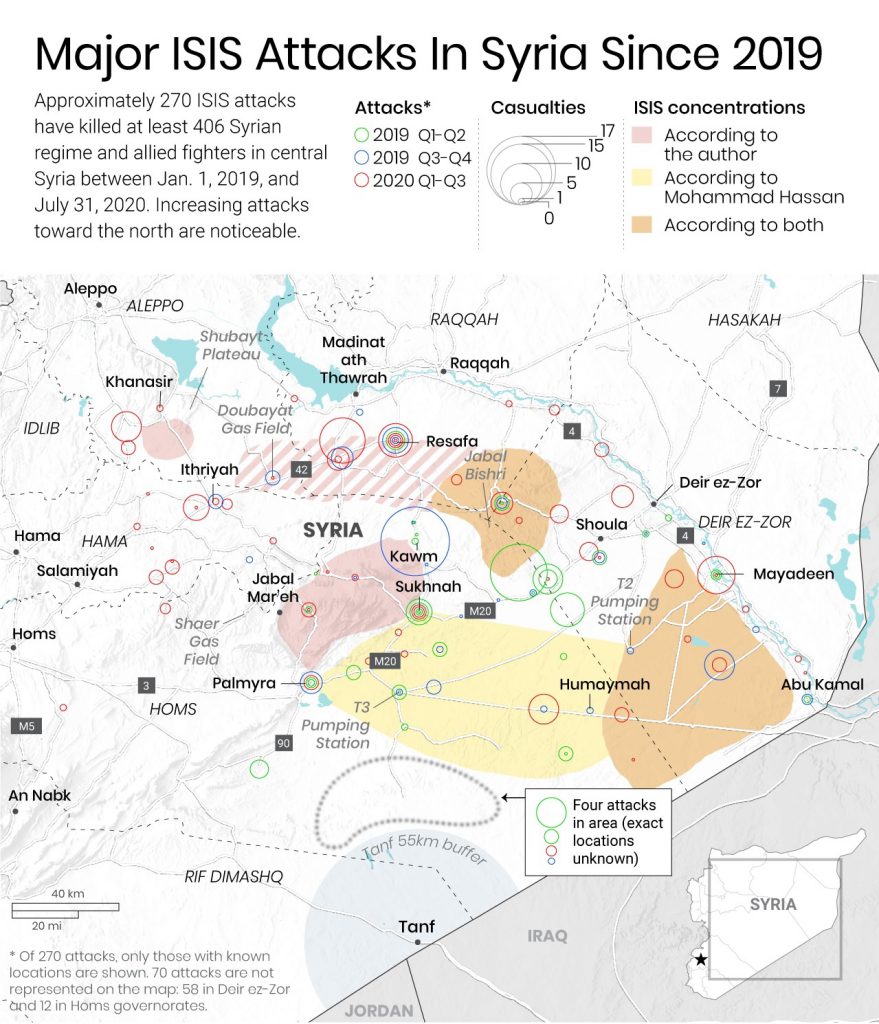

ISIS has stepped into and widened these gaps between Deiri locals and their respective governing and security bodies. In regime areas, ISIS tactics appear more incidental, deepening local anger at the Syrian Arab Army (SAA) by creating general instability through increased attacks on shepherds and local militias. However, in areas of northeast Syria under the SDF, ISIS appears to be implementing an explicit strategy of fomenting security and political chaos by targeting local leaders allied with the SDF, reminiscent of the Islamic State in Iraq’s strategy to undermine the tribal Awakening Councils 10 years ago.2

In both cases, the respective governing bodies are failing to secure the loyalty and support of locals. The security structures built in Deir ez-Zor by the regime and the AANES have coopted and incorporated local tribes to a significant extent, but a lack of support from the central governing bodies amid increasing ISIS attacks threatens long-term stability in the province. These two regional dynamics are outlined and compared below to illustrate the dual challenges both governance bodies face in appealing to locals and thwarting the resurgence of ISIS in Deir ez-Zor.

Security & the Tribes

Gaining the support of local tribes, or at least the appearance of support, is crucial for the regime to bolster its legitimacy in central Syria and improve the security situation in the towns once ruled by ISIS. As Ziad Awad wrote in 2018, Damascus “also needs the local population to help achieve its plan to revive economic production … as well as for its military plan to establish Self-Defence Units. Likewise, on a symbolic level, the regime’s sphere of influence in the region … will remain practically meaningless as long as that area is nearly uninhabited.”3

Following its military victory, Damascus was forced to rely on “middlemen from unofficial centres of power,” such as tribal leaders, to secure social and political control, writes Awad. For example, in October 2017 Sheikh Ibrahim al-Dayir released a statement4 on behalf of the Shaytat tribe, stating that his militia was the only force allowed to enter Shaytat villages previously under ISIS control. The Shaytat tribe’s relationship with the regime is indicative of the pragmatic utilization of tribal forces and figures in pre- and post-ISIS landscapes, whereby the regime offered tribal authorities access to a larger security apparatus (and the opportunity for revenge) as well as political and status incentives.

The rise of ISIS in 2014 forced many tribes and clans to abandon Free Syrian Army (FSA) groups and the Nusra Front and commit either to ISIS or Assad. Nowhere was this clearer than with the well-documented Shaytat massacre in August 2014, when ISIS militants killed more than 700 members of the Shaytat tribe, both civilians and fighters, after they refused to join the group or leave their towns.5 Shaytat tribesmen then split, with some joining the SDF and others joining nearby regime forces.

Abdel Basset Khalef’s Shaytat militia exemplifies the common transition in Deir ez-Zor from anti-regime tribal militia to incorporation into the regime’s forces. According to Syria researcher Suheil al-Ghazi, Khalef was once the commander of the anti-regime Shaytat militia Thuwar Ashaer. However, following the 2014 massacre, he and most of his fighters fled to nearby regime-held areas, where they joined forces with the local Republican Guard brigade. According to various Facebook posts by the group’s fighters, Khalef renamed his militia Aswed Sharqiyah6 and began working alongside 104th Brigade’s Issam Zahreddine. Khalef was killed7 in combat in August 2015, but his militia continues8 to operate today as an explicitly Shaytat auxiliary of the Deir ez-Zor-based Republican Guard brigade.

The Shaytat clans’ role in bolstering both pro-Assad and SDF armed forces following the 2014 massacre has been well documented. However, the role of the Busaraya tribe in supporting Damascus’ security apparatus is less discussed. Historically concentrated along the strategically important belt of towns stretching from Deir ez-Zor city, north to Ma’adan, and west along the Deir ez-Zor-Damascus highway to Shoula, the Busaraya tribe has always been overwhelmingly anti-ISIS, with minimal presence among anti-regime forces.9 According to the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, the Busaraya’s anti-regime forces were largely confined to the faction of Abu Abdul Rahman al-Aqaisi, Jabhat al-Nusra’s western Deir ez-Zor emir until his death in April 2013, and to two factions from the Albu Mohammad clan in Buqrus and the Bu-Shuaib clan in Kharitiya, both of which joined Ahrar al-Sham by 2013.10 Indeed, some Busaraya who remained under ISIS rule even went so far as to attack ISIS fighters who had entered their village in September 2016.11

Both the tribe’s official sheikh, Muhana Faisal Ahmad al-Fayyad, and prominent leader Sheikh Ahmad Shalash, are ardently pro-Assad, with Fayyad having served in Syria’s People’s Assembly since 2011 and the Hezbollah-friendly Shalash splitting time between Beirut and Damascus.12 Damascus relied heavily on the Busaraya when first forming the Deir ez-Zor branch of its National Defense Forces (NDF) militia and later when it expanded the NDF following the successful recapture of Deir ez-Zor Province from ISIS.

According to Syria expert Muhammad Hassan, the tribes first began to heavily support the NDF after the rise of ISIS, when many opposition tribal fighters joined the pro-government militia. Accordingly, the NDF began to change and take on an increasingly tribal character. Firas Jeham, the long-time commander of the Deir ez-Zor NDF, has historically appointed sector commanders from the most prominent tribes in each sector. These commanders recruit heavily from within the local tribes, ensuring that each sector is organized by tribe. Mohammad Hassan further states that following the regime’s recapture of Deir ez-Zor in 2017, men from all the tribes in the area “began joining the defense forces for economic and other reasons to protect them from being pursued by the regime’s intelligence services and forcing them to perform military service.” Thus, the NDF in Deir ez-Zor can be viewed as an extension of the tribes, and the main source of tribal empowerment in the security sector.

Jeham is himself a local, although he has no relevant tribal connections. According to one NDF fighter, Jeham began the war leading a criminal gang in the city of Deir ez-Zor before being recruited into the NDF in 2013. He has been described to the authors as non-ideological — someone “who could have been ISIS, FSA, or whatever really.” Despite his lack of tribal ties or ideological support for the regime, Jeham has maintained significant tribal support. In an interview with the authors, an NDF fighter described the relationship accordingly: “Herders and locals might get harassed by militias, IRGC [Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps], and SAA from other parts of the country that think of them as backwards and simple, but never with NDF under Firas because he is from their area and knows how to handle difficult matters.”

While Jeham and the NDF have local support, it is the more traditional Maj. Gen. Ghassan Mohammad who retains the backing of Damascus and the SAA. Mohammad has served as the commander of the Deir ez-Zor-based 17th Infantry Division since December 2017 and was appointed13 the head of the Deir ez-Zor Military and Security Committee in November 2019. In control of both the 17th Division, the unit historically in charge of eastern Syria, and the Security Committee, ostensibly in charge of all military and security operations in the governorate, Mohammed theoretically should be firmly in command of Jeham and the NDF.

However, according to local reports, Jeham has continuously fought Mohammad’s control, vying for independence from the SAA. According to one NDF member, over a year of political infighting came to a head in June 2020 when Mohammad attempted to strip Jeham of his position and force the NDF under the command of the 17th Division. The Russians reportedly stepped in and deescalated things, but the NDF and SAA remain unwilling or unable to conduct joint anti-ISIS operations in the province.

“The tribes first began to heavily support the NDF after the rise of ISIS, when many opposition tribal fighters joined the pro-government militia. Accordingly, the NDF began to change and take on an increasingly tribal character. … [Now] the NDF in Deir ez-Zor can be viewed as an extension of the tribes, and the main source of tribal empowerment in the security sector.”

ISIS Threatens the Busaraya & Regime Control

With Maj. Gen. Ghassan Mohammad and the SAA all but refusing to support the NDF, local forces have been left even more vulnerable to increased ISIS attacks. On Aug. 27, 2020, ISIS militants ambushed a group of pro-regime NDF fighters just west of the village of Musarib.14 NDF Facebook pages reported as many as 15 fighters were lost, including NDF Western Sector Commander Nizar Kharfan, while a local militiaman told the authors that more than 30 men were killed or missing.

There are several conflicting narratives on how the ambush played out, but the general details appear to be that ISIS militants either kidnapped shepherds in Musarib and brought them to the desert plains west of the town, or the militants ambushed the shepherds while they were already in the desert. In either case, ISIS fighters killed the shepherds and their sheep, while allowing news of the attack to reach the NDF. Kharfan and his NDF fighters were locals, Busaraya tribesmen who themselves were born in or near Musarib. They set off in search of the missing shepherds, only to be ambushed and killed.

The attacks triggered a massive mobilization of Busaraya tribal members who felt unsupported by the SAA. “The tribes have been abandoned in the desert,” is how one local fighter described the mood to the authors. Busaraya contingents from the pro-regime Liwa al-Quds,15 Qaterji Forces,16 and the NDF arrived in Musarib over the next two days, joining local tribesmen mobilized by the Busaraya Sheikh al-Fayyad, ready to conduct their own anti-ISIS operations, without the SAA.

ISIS attacks have surged recently in the urban belt between Deir ez-Zor city and Ma’adan, Raqqa. Attacks in west Deir ez-Zor in 2019 were focused around Shoula and Jabal Bishri, but in January 2020, ISIS militants conducted their first attack north of Deir ez-Zor, killing five shepherds near Tel Hajif. ISIS then continued to establish its presence in the region throughout May and August, targeting locals and Iranian forces alike at least six times in four different Busaraya towns. The deaths of Commander Kharfan and his fellow tribesmen were just the next in a series of crises that has driven a wedge between the Busaraya and Damascus.

The Aug. 27 massacre triggered two immediate reactions. First, Busaraya tribesmen from various militias mobilized for their own anti-ISIS operations, all with the support of the NDF. Sheikh al-Fayyad formed a new tribal unit, called the “Forces of the Fighters of the Tribes of the Busaraya Clan.” According to a member of that new unit, this force, which will eventually merge with the NDF, “will seek vengeance against ISIS and will not be supported by other tribes or the regime.” An NDF member told the authors that Jeham opened several warehouses of weapons to these tribal fighters, a claim supported by videos showing NDF-marked vehicles among the tribal force.

Second, according to a member of the NDF, an emergency meeting was held between the NDF and the SAA on Aug. 28. Maj. Gen. Mohammad reportedly agreed to increase security cooperation with the NDF and deploy 17th Division units north of Deir ez-Zor city for the first time. However, as of publication, these promises have not been met, with the SAA claiming a need for more training. During this delay, at least eight more NDF fighters have been killed in clashes with the estimated 100-man-strong ISIS cell west of Musarib on Sept. 7 and Sept. 18. Nearly all of the slain men come from the Busaraya. Meanwhile, Mohammad continues to bring new 17th Division recruits to Deir ez-Zor, mostly men arrested at checkpoints in western Syria, in an apparent bid to out-gun Jeham.

With the gaps between the regime and the tribes widening, Maj. Gen. Nizar Khaddour, formerly a brigade commander in the 5th Corps, was appointed17 deputy commander of the 17th Division on Aug. 26, just two days before the first attacks. Khaddour hails from the Busaraya tribe and is presumably close to the Russians thanks to his time in the 5th Corps. He represents one possible solution for Damascus, allowing the regime to replace Mohammad with someone with local support. However, Jeham, in an unusual move, has replaced the slain Busaraya commander Kharfan with a relatively unknown man from Jeham’s own family. Jeham and several members of the NDF’s Central Committee personally visited Musarib on Sept. 8 to receive the Busaraya tribe’s blessing for the new appointment — an event at which SAA representatives were noticeably absent.18 Despite this, Jeham’s insistence on centralizing as much power as possible around himself has the potential to anger tribal leaders.

The Aqidat Assassination

Jeham is also busy attempting to gain the support of tribes currently split under SDF rule. He wasted no time in expressing his support for the Aqidat tribe after the assassination of Aqidat Sheikh Mutsher Hamud Jeidan al-Hifl on Aug. 2. In a concurrent video statement, he called for unity among the tribes against the American forces and the SDF.

Jeham had been ramping up outreach to the Deir ez-Zor tribes for months now. In June, he and the now-deceased NDF commander Kharfan met with a council of sheikhs and tribal leaders19 in Deir ez-Zor, where Jeham called for “tribal unity” and rejection of the “occupiers seeking to spread discord” after a feud between the Bakir and al-Bu Frio clans in SDF territory resulted in eight deaths.20 These attempts to court tribal leaders were followed by SDF Gen. Mazloum Abdi’s own meetings in July with tribes in Deir ez-Zor regarding security complaints and detainees.21

As with tribal-regime relationships, tribes are often split in their loyalty to the SDF. The Aqidat, a tribal confederation that includes the Shaytat and is loosely related to the Busaraya, is the largest and most influential tribal authority in the region. Since ISIS’s territorial demise, the Aqidat proved a valuable SDF ally in anti-ISIS operations.22 However, prominent Aqidat figures have come out in support of both the SDF and the regime.

Throughout 2019, Aqidat Sheikh Jamil Rashid al-Hafal was known to host tribal conferences at which he reportedly encouraged cooperation with the Coalition and rejected regime, Russian, and Iranian influence in Deir ez-Zor. This call for cooperation was likely connected to the U.S.’s recent reassurances that it would remain in Syria to secure oil fields.23 Likewise, some members of the Shaytat tribe have expressed eagerness to deal directly with the Coalition. Importantly, Deir ez-Zor’s tribes appear to largely differentiate between the AANES, which they often view as a foreign governing body, and the Coalition, which is seen as a crucial partner in deterring ISIS attacks.24

As with the tribes in regime-held areas, those in SDF-held areas have suffered from increasing ISIS attacks throughout the region. Two days before the assassination of Sheikh Mutsher Hamud Jeidan al-Hifl, ISIS claimed a similar attack that resulted in the death of the spokesman for the Aqidat tribe, Suleiman al-Kassar. Local pro-NDF Facebook pages and some members of the Aqidat attributed the early August attacks to SDF forces, signaling divisions. The incident exacerbated tensions between tribes in Deir ez-Zor and the AANES. On Aug. 4, demonstrators took to the streets in the SDF-held towns of al-Shuhayl, Theban, and al-Hawayij. The protesters demanded that the SDF and the Coalition reveal the identities of the assassins, and the Aqidat tribe issued an ultimatum that the Coalition and the SDF had one month to find the sheikh’s killers.

Protests continued in al-Hawayij, Theban, and Bassr days after the assassination. In the regime-held town of Mayadeen bordering al-Hawayij, protesters gathered near the bridge between the two cities and demonstrated with NDF soldiers. Armed gunmen took control of several SDF posts and the al-Hawayij school. In Basser, the SDF withdrew from their posts to avoid conflict with demonstrators, and in al-Shahyl it imposed curfews and blocked entry into the city on the Hawayj Road.

However, on Aug. 5, members of the Aqidat tribe, Coalition representatives, and SDF officials — including the head of the Deir ez-Zor Military Council — met to discuss the Aqidat’s demands. The Aqidat representatives agreed to stop protesting for a month while the SDF investigated the murder.

The following morning SDF soldiers arrested six civilians, five of which belonged to the same family, in al-Shuhayl. Officially, it is unknown if these arrests were made in response to the assassination or other factors. In the days that followed, the SDF and the Coalition continued to make arrests, and representatives initiated a series of meetings with local sheikhs. Pro-SDF Raqqa tribes shared diplomatic messages of support for the Aqidat tribe, and in an Aug. 8 meeting, Deir ez-Zor tribal representatives demanded that the Coalition share intelligence with the SDF to address the worsening security issues.

The SDF’s Deir ez-Zor Dilemma

Although the SDF reinstated order, the incident is indicative of the larger security issues in Deir ez-Zor that have been exacerbated by the increase in ISIS attacks. Tribe members are beholden to local security forces and enjoy limited political authority, while simultaneously bearing the brunt of the security threats. The SDF also faces a greater issue with local legitimacy than is the case in other provinces, and the difficult economic situation provides little margin to secure the livelihoods of locals. Ideological and representational issues also divide the tribes into independent factions and coalitions subordinate to prominent leaders.

Tribes have long expressed their discontent with empty Arab representation in the SDF and the AANES, and the tribes’ demand for a direct line to the Coalition is not new.26 In addition, the SDF’s security apparatus is over-stretched, with the current levels of Coalition support insufficient to address the ISIS threat. Even as many tribes have requested more support against ISIS, the SDF has proven, much like the regime forces, unable to disrupt its activity. In a July interview with the authors, SDF commander Gen. Mazloum Abdi was not optimistic about the SDF’s ability to reduce ISIS attacks in northeast Syria, stating that anti-ISIS operations will likely only stabilize the number of attacks over the coming months. This inability to provide security has reduced the tribes’ incentives to work with the SDF.

As with the regime and the “Forces of the Fighters of the Tribes” affiliated with Military Intelligence, the SDF has utilized tribal members’ local knowledge in anti-ISIS operations.27 However, the SDF lacked the resources to adequately vet and develop new intelligence networks after laying claim to the eastern province, and according to the International Crisis Group, it relies “on pre-existing structures that ISIS created to co-opt tribes as informants for the group’s security branches.”28 This misstep has led to unreliable intelligence, deployment of “resources to fighting ISIS in areas where it was not present” and, in some cases, increased civilian casualties.29

Likewise, allegations of politically motivated arrests by SDF soldiers of locals only serve to stoke Arab resentment.30 Just a week after the protests began in Deir ez-Zor, the SDF released nine detainees from the villages of al-Shuhayl and Ziban upon the request of tribal leaders.31

In recent weeks the SDF has ramped up anti-ISIS operations in the region, but many arrests have resulted in new complaints. On Sept. 8, the SDF arrested the head of the Deir ez-Zor Civil Council.32 Later that day it killed one and arrested six others in the nearby village of Jadid Akidat. According to a Shaytat tribe Telegram channel, the SDF also recently arrested the head of the Shaytat Tribe Martyrs Association after he demanded that the salaries for martyrs be paid out of oil profits.33

The imprisoned Shaytat tribesman’s complaint about the tribe’s cut of oil profits is a recurring point of contention. Deir ez-Zor residents have frequently protested against the SDF’s fuel policy and division of oil revenues. In 2019, the former head of the Deir ez-Zor Civil Council negotiated with the Shaytat tribesmen over this issue but they continue to express their frustration with the distribution of revenue as well as the allegedly SDF-affiliated oil security militias.34

Over a month after the deadline set by Aqidat tribesmen for the SDF to apprehend the assassins, al-Shuhayl has reportedly formed a new local security force. A prominent Shaytat Telegram channel claims that the force is a local tribal security force and is not subject to the SDF (despite their newly appointed commander’s immediate departure for training in Qamishli). The force was allegedly created through direct negotiations with the Coalition and will not be deployed outside of al-Shuhayl.

As tribesmen address their own security, the threat in Deir ez-Zor continues to increase for SDF officials with the assassination of a tribal member of the Al-Shuhayl Civil Council,35 the killing of an SDF commander in Busayra,36 and the fourth assassination attempt of Deir ez-Zor Military Council co-chair Laila al-Abdullah.37

Conclusion

On both sides of the Euphrates, security structures are the only source of real local empowerment, either through the Deir ez-Zor Military Council or the NDF. However, mismanagement of these relationships and security strategies by the regime and the SDF threaten stability. The SDF has a haphazard method of releasing and “reintegrating” former ISIS tribal members. Combined with what the International Crisis Group describes as developing “mutual ‘non-aggression’ pacts with tribes, arranged through a mix of intimidation and persuasion, playing on the lack of trust between locals and SDF authorities,” this has created a window of opportunity and a weak point for ISIS to exploit in Deir ez-Zor.

Similarly, with ISIS attacks on the rise across the Badia, and particularly in western Deir ez-Zor, the NDF’s and SAA’s need, or lack thereof, to court the tribes is all the more crucial. The current security situation in western Deir ez-Zor remains untenable, despite the Busaraya mobilization, without increased military support to local forces from Damascus and joint operations between the SAA and NDF. But the divide between these two forces will continue to grow and the security situation is only likely to deteriorate as long as Jeham or Maj. Gen. Mohammad remain in their posts.

Continued local and tribal support hinges upon the degree to which these institutions — the NDF, SAA, and SDF — succeed in their fight against ISIS and local criminal organizations. Much of this rests upon the support that governing bodies provide to the local security forces. There are already some communities in northeast Syria that view the SDF as incapable of dealing with ISIS and have begun reaching out to the militants to end the attacks.

Pressingly, according to ISIS researcher Calibre Obscura, some unofficial ISIS channels began claiming in September that ISIS will “soon” begin targeting the leadership of the Busaraya tribe in retaliation for their mobilization following the Aug. 27 attack — a sign that ISIS may begin importing the strategies it has used in northeast Syria to the areas under regime control.38 While it is doubtful any portion of the Busaraya will join ISIS, the combination of a lack of security support and attacks against local leaders and the civilian population will push other Deiris under regime rule to cut deals with ISIS, further strengthening the group’s presence in the region.