In 2016 and 2017, US management consultancy giant McKinsey was at the heart of efforts in Europe to accelerate the processing of asylum applications on over-crowded Greek islands and salvage a controversial deal with Turkey, raising concerns over the outsourcing of public policy on refugees.

The language was more corporate boardroom than humanitarian crisis – promises of ‘targeted strategies’, ‘maximising productivity’ and a ‘streamlined end-to-end asylum process.’

But in 2016 this was precisely what the men and women of McKinsey&Company, the elite US management consultancy, were offering the European Union bureaucrats struggling to set in motion a pact with Turkey to stem the flow of asylum seekers to the continent’s shores.

In March of that year, the EU had agreed to pay Turkey six billion euros if it would take back asylum seekers who had reached Greece – many of them fleeing fighting in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan – and prevent others from trying to cross its borders.

The pact – which human rights groups said put at risk the very right to seek refuge – was deeply controversial, but so too is the previously unknown extent of McKinsey’s influence over its implementation, and the lengths some EU bodies went to conceal that role.

According to the findings of this investigation, months of ‘pro bono’ fieldwork by McKinsey fed, sometimes verbatim, into the highest levels of EU policy-making regarding how to make the pact work on the ground, and earned the consultancy a contract – awarded directly, without competition – worth almost one million euros to help enact that very same policy.

The bloc’s own internal procurement watchdog later deemed the contract “irregular”.

Questions have already been asked about McKinsey’s input in 2015 into German efforts to speed up its own turnover of asylum applications, with concerns expressed about rights being denied to those applying.

This investigation, based on documents sought since November 2017, sheds new light on the extent to which private management consultants shaped Europe’s handling of the crisis on the ground, and how bureaucrats tried to keep that role under wraps.

“If some companies develop programs which then turn into political decisions, this is a political issue of concern that should be examined carefully,” said German MEP Daniel Freund, a member of the European Parliament’s budget committee and a former Head of Advocacy for EU Integrity at Transparency International.

“Especially if the same companies have afterwards been awarded with follow-up contracts not following due procedures.”

Deal too important to fail

The March 2016 deal was the culmination of an epic geopolitical thriller played out in Brussels, Ankara and a host of European capitals after more than 850,000 people – mainly Syrians, Iraqis and Afghans – took to the Aegean by boat and dinghy from Turkey to Greece the previous year.

Turkey, which hosts some 3.5 million refugees from the nine-year-old war in neighbouring Syria, committed to take back all irregular asylum seekers who travelled across its territory in return for billions of euros in aid, EU visa liberalisation for Turkish citizens and revived negotiations on Turkish accession to the bloc. It also provided for the resettlement in Europe of one Syrian refugee from Turkey for each Syrian returned to Turkey from Greece.

The EU hailed it as a blueprint, but rights groups said it set a dangerous precedent, resting on the premise that Turkey is a ‘safe third country’ to which asylum seekers can be returned, despite a host of rights that it denies foreigners seeking protection.

The deal helped cut crossings over the Aegean, but it soon became clear that other parts were not delivering; the centrepiece was an accelerated border procedure for handling asylum applications within 15 days, including appeal. This wasn’t working, while new movement restrictions meant asylum seekers were stuck on Greek islands.

But for the EU, the deal was too important to be derailed.

“The directions from the European Commission, and those behind it, was that Greece had to implement the EU-Turkey deal full-stop, no matter the legal arguments or procedural issue you might raise,” said Marianna Tzeferakou, a lawyer who was part of a legal challenge to the notion that Turkey is a safe place to seek refuge.

“Someone gave an order that this deal will start being implemented. Ambiguity and regulatory arbitrage led to a collapse of procedural guarantees. It was a political decision and could not be allowed to fail.”

Enter McKinsey.

Action plans emerge simultaneously

Fresh from advising Germany on how to speed up the processing of asylum applications, the firm’s consultants were already on the ground doing research in Greece in the summer of 2016, according to two sources working with the Greek asylum service, GAS, at the time but who did not wish to be named.

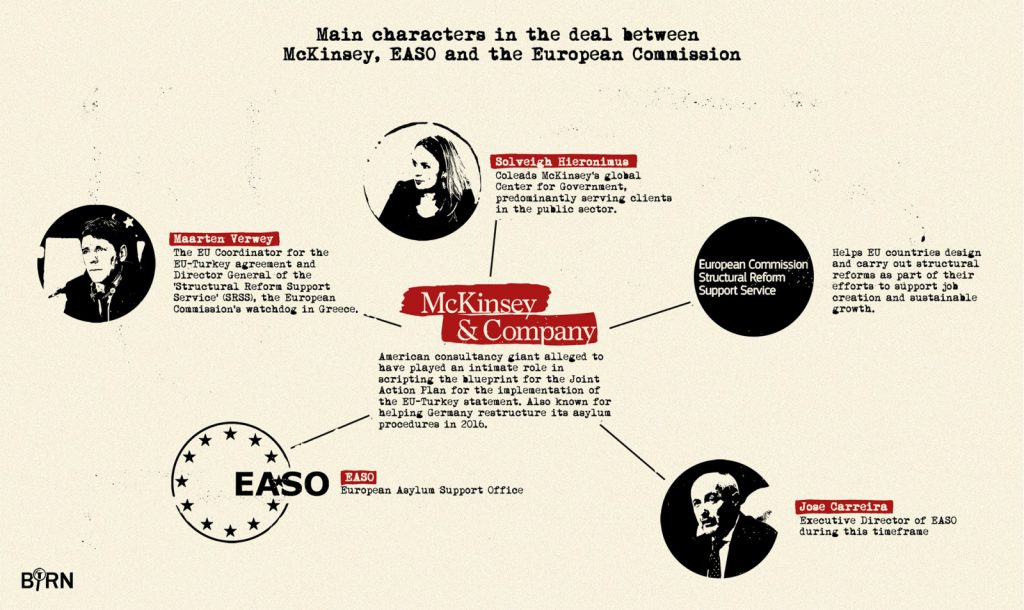

Documents seen by BIRN show that the consultancy was already in “initial discussions” with an EU body called the ‘Structural Reform Support Service’, SRSS, which aids member states in designing and implementing structural reforms and was at the time headed by Dutchman Maarten Verwey. Verwey was simultaneously EU coordinator for the EU-Turkey deal and is now the EU’s director general of economic and financial affairs, though he also remains acting head of SRSS.

Asked for details of these ‘discussions’, Verwey responded that the European Commission – the EU’s executive arm – “does not hold any other documents” concerning the matter.

Nevertheless, by September 2016, McKinsey had a pro bono proposal on the table for how it could help out, entitled ‘Supporting the European Commission through integrated refugee management.’ Verwey signed off on it in October.

Minutes of management board meetings of the European Asylum Support Office, EASO – the EU’s asylum agency – show McKinsey was tasked by the Commission to “analyse the situation on the Greek islands and come up with an action plan that would result in an elimination of the backlog” of asylum cases by April 2017.

A spokesperson for the Commission told BIRN: “McKinsey volunteered to work free of charge to improve the functioning of the Greek asylum and reception system.”

Over the next 12 weeks, according to other redacted documents, McKinsey worked with all the major actors involved – the SRSS, EASO, the EU border agency Frontex as well as Greek authorities.

At bi-weekly stakeholder meetings, McKinsey identified “bottlenecks” in the asylum process and began to outline a series of measures to reduce the backlog, some of which were already being tested in a “mini-pilot” on the Greek island of Chios.

At a first meeting in mid-October, McKinsey consultants told those present that “processing rates” of asylum cases by the EASO and the Greek asylum service, as well as appeals bodies, would need to significantly increase.

By December, McKinsey’s “action plan” was ready, involving “targeted strategies and recommendations” for each actor involved.

The same month, on December 8, Verwey released the EU’s own Joint Action Plan for implementing the EU-Turkey deal, which was endorsed by the EU’s heads of government on December 15.

There was no mention of any McKinsey involvement and when asked about the company’s role the Commission told BIRN the plan was “a document elaborated together between the Commission and the Greek authorities.”

However, buried in the EASO’s 2017 Annual Report is a reference to European Council endorsement of “the consultancy action plan” to clear the asylum backlog.

Indeed, the similarities between McKinsey’s plan and the EU’s Joint Action Plan are uncanny, particularly in terms of increasing detention capacity on the islands, “segmentation” of cases, ramping up numbers of EASO and GAS caseworkers and interpreters and Frontex escort officers, limiting the number of appeal steps in the asylum process and changing the way appeals are processed and opinions drafted.

In several instances, they are almost identical: where McKinsey recommends introducing “overarching segmentation by case types to increase speed and quality”, for example, the EU’s Joint Action Plan calls for “segmentation by case categories to increase speed and quality”.

Much of what McKinsey did for the SRSS remains redacted.

In June 2019, the Commission justified the non-disclosure on the basis that the information would pose a “risk” to “public security” as it could allegedly “be exploited by third parties (for example smuggling networks)”.

Full disclosure, it argued, would risk “seriously undermining the commercial interests” of McKinsey.

“While I understand that there could indeed be a private and public interest in the subject matter covered by the documents requested, I consider that such a public interest in transparency would not, in this case, outweigh the need to protect the commercial interests of the company concerned,” Martin Selmayr, then secretary-general of the European Commission, wrote.

SRSS rejected the suggestion that the fact that Verwey refused to fully disclose the McKinsey proposal he had signed off on in October 2016 represented a possible conflict of interest, according to internal documents obtained during this investigation.

Once Europe’s leaders had endorsed the Joint Action Plan, EASO was asked to “conclude a direct contract with McKinsey” to assist in its implementation, according to EASO management board minutes.

‘Political pressure’

The contract, worth 992,000 euros, came with an attached ‘exception note’ signed on January 20, 2017, by EASO’s Executive Director at the time, Jose Carreira, and Joanna Darmanin, the agency’s then head of operations. The note stated that “due to the time constraints and the political pressure it was deemed necessary to proceed with the contract to be signed without following the necessary procurement procedure”.

The following year, an audit of EASO yearly accounts by the European Court of Auditors, ECA, which audits EU finances, found that “a single pre-selected economic operator” had been awarded work without the application of “any of the procurement procedures” laid down under EU regulations, designed to encourage transparency and competition.

“Therefore, the public procurement procedure and all related payments (992,000 euros) were irregular,” it said.

The auditor’s report does not name McKinsey. But it does specify that the “irregular” contract concerned the EASO’s hiring of a consultancy for implementation of the action plan in Greece; the amount cited by the auditor exactly matches the one in the McKinsey contract, while a spokesman for the EASO indirectly confirmed the contracts concerned were one and the same.

When asked about the McKinsey contract, the spokesman, Anis Cassar, said: “EASO does not comment on specifics relating to individual contracts, particularly where the ECA is concerned. However, as you note, ECA found that the particular procurement procedure was irregular (not illegal).”

“The procurement was carried under [sic] exceptional procurement rules in the context of the pressing requests by the relevant EU Institutions and Member States,” said EASO spokesman Anis Cassar.

McKinsey’s deputy head of Global Media Relations, Graham Ackerman, said the company was unable to provide any further details.

“In line with our firm’s values and confidentiality policy, we do not publicly discuss our clients or details of our client service,” Ackerman told BIRN.

‘Evaluation, feedback, goal-setting’

It was not the first time questions had been asked of the EASO’s procurement record.

In October 2017, the EU’s fraud watchdog, OLAF, launched a probe into the agency, chiefly concerning irregularities identified in 2016. It contributed to the resignation in June 2018 of Carreira, who co-signed the ‘exception note’ on the McKinsey contract. The investigation eventually uncovered wrongdoings ranging from breaches of procurement rules to staff harassment, Politico reported in November 2018.

According to the EASO, the McKinsey contract was not part of OLAF’s investigation. OLAF said it could not comment.

McKinsey’s work went ahead, running from January until April 2017, the point by which the EU wanted the backlog of asylum cases “eliminated” and the burden on overcrowded Greek islands lifted.

Overseeing the project was a steering committee comprised of Verwey, Carreira, McKinsey staff and senior Greek and European Commission officials.

The details of McKinsey’s operation are contained in a report it submitted in May 2017.

The EASO initially refused to release the report, citing its “sensitive and restrictive nature”. Its disclosure, the agency said, would “undermine the protection of public security and international relations, as well as the commercial interests and intellectual property of McKinsey & Company.”

The response was signed by Carreira.

Only after a reporter on this story complained to the EU Ombudsman, did the EASO agree to disclose several sections of the report.

Running to over 1,500 pages, the disclosed material provides a unique insight into the role of a major private consultancy in what has traditionally been the realm of public policy – the right to asylum.

In the jargon of management consultancy, the driving logic of McKinsey’s intervention was “maximising productivity” – getting as many asylum cases processed as quickly as possible, whether they result in transfers to the Greek mainland, in the case of approved applications, or the deportation of “returnable migrants” to Turkey.

“Performance management systems” were introduced to encourage speed, while mechanisms were created to “monitor” the weekly “output” of committees hearing the appeals of rejected asylum seekers.

Time spent training caseworkers and interviewers before they were deployed was to be reduced, IT support for the Greek bureaucracy was stepped up and police were instructed to “detain migrants immediately after they are notified of returnable status,” i.e. as soon as their asylum applications were rejected.

Four employees of the Greek asylum agency at the time told BIRN that McKinsey had access to agency staff, but said the consultancy’s approach jarred with the reality of the situation on the ground.

Taking part in a “leadership training” course held by McKinsey, one former employee, who spoke on condition of anonymity, told BIRN: “It felt so incompatible with the mentality of a public service operating in a camp for asylum seekers.”

The official said much of what McKinsey was proposing had already been considered and either implemented or rejected by GAS.

“The main ideas of how to organise our work had already been initiated by the HQ of GAS,” the official said. “The only thing McKinsey added were corporate methods of evaluation, feedback, setting goals, and initiatives that didn’t add anything meaningful.”

Indeed, the backlog was proving hard to budge.

Throughout successive “progress updates”, McKinsey repeatedly warned the steering committee that productivity “levels are insufficient to reach target”. By its own admission, deportations never surpassed 50 a week during the period of its contract. The target was 340.

In its final May 2017 report, McKinsey touted its success in “reducing total process duration” of the asylum procedure to a mere 11 days, down from an average of 170 days in February 2017.

Yet thousands of asylum seekers remained trapped in overcrowded island camps for months on end.

While McKinsey claimed that the population of asylum seekers on the island was cut to 6,000 by April 2017, pending “data verification” by Greek authorities, Greek government figures put the number at 12,822, just around 1,500 fewer than in January when McKinsey got its contract.

The winter was harsh; organisations working with asylum seekers documented a series of accidents in which a number of people were harmed or killed, with insufficient or no investigation undertaken by Greek authorities.

McKinsey’s final report tallied 40 field visits and more than 200 meetings and workshops on the islands. It also, interestingly, counted 21 weekly steering committee meetings “since October 2016” – connecting McKinsey’s 2016 pro bono work and the 2017 period it worked under contract with the EASO. Indeed, in its “project summary”, McKinsey states it was “invited” to work on both the “development” and “implementation” of the action plan in Greece.

The Commission, however, in its response to this investigation, insisted it did not “pre-select” McKinsey for the 2017 work or ask EASO to sign a contract with the firm.

Smarting from military losses in Syria and political setbacks at home, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan tore up the deal with the EU in late February this year, accusing Brussels of failing to fulfil its side of the bargain. But even before the deal’s collapse, 7,000 refugees and migrants reached Greek shores in the first two months of 2020, according to the United Nations refugee agency.

German link

This was not the first time that the famed consultancy firm had left its mark on Europe’s handling of the crisis.

In what became a political scandal, the German Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, according to reports, paid McKinsey more than €45 million to help clear a backlog of more than 270,000 asylum applications and to shorten the asylum process.

German media reports said the sum included 3.9 million euros for “Integrated Refugee Management”, the same phrase McKinsey pitched to the EU in September 2016.

The parallels don’t end there.

Much like the contract McKinsey clinched with the EASO in January 2017, German media reports have revealed that more than half of the sum paid to the consultancy for its work in Germany was awarded outside of normal public procurement procedures on the grounds of “urgency”. Der Spiegel reported that the firm also did hundreds of hours of pro bono work prior to clinching the contract. McKinsey denied that it worked for free in order to win future federal contracts.

Again, the details were classified as confidential.

Arne Semsrott, director of the German transparency NGO FragdenStaat, which investigated McKinsey’s work in Germany, said the lack of transparency in such cases was costing European taxpayers money and control.

Asked about German and EU efforts to keep the details of such outsourcing secret, Semsrott told BIRN: “The lack of transparency means the public spending more money on McKinsey and other consulting firms. And this lack of transparency also means that we have a lack of public control over what is actually happening.”

Sources familiar with the decision-making in Athens identified Solveigh Hieronimus, a McKinsey partner based in Munich, as the coordinator of the company’s team on the EASO contract in Greece. Hieronimus was central in pitching the company’s services to the German government, according to German media reports.

Hieronimus did not respond to BIRN questions submitted by email.

Freund, the German MEP formerly of Transparency International, said McKinsey’s role in Greece was a cause for concern.

“It is not ideal if positions adopted by the [European] Council are in any way affected by outside businesses,” he told BIRN. “These decisions should be made by politicians based on legal analysis and competent independent advice.”

A reporter on this story again complained to the EU Ombudsman in July 2019 regarding the Commission’s refusal to disclose further details of its dealings with McKinsey.

In November, the Ombudsman told the Commission that “the substance of the funded project, especially the work packages and deliverable of the project[…] should be fully disclosed”, citing the principle that “the public has a right to be informed about the content of projects that are financed by public money.” The Ombudsman rejected the Commission’s argument that partial disclosure would undermine the commercial interests of McKinsey.

Commission President Ursula von Der Leyen responded that the Commission “respectfully disagrees” with the Ombudsman. The material concerned, she wrote, “contains sensitive information on the business strategies and the commercial relations of the company concerned.”

The president of the Commission has had dealings with McKinsey before; in February, von der Leyen testified before a special Bundestag committee concerning contracts worth tens of millions of euros that were awarded to external consultants, including McKinsey, during her time as German defence minister in 2013-2019.

In 2018, Germany’s Federal Audit Office said procedures for the award of some contracts had not been strictly lawful or cost-effective. Von der Leyen acknowledged irregularities had occurred but said that much had been done to fix the shortcomings.

She was also questioned about her 2014 appointment of Katrin Suder, a McKinsey executive, as state secretary tasked with reforming the Bundeswehr’s system of procurement. Asked if Suder, who left the ministry in 2018, had influenced the process of awarding contracts, von der Leyen said she assumed not. Decisions like that were taken “way below my pay level,” she said.

In its report, Germany’s governing parties absolved von der Leyen of blame, Politico reported on June 9.

The EU Ombudsman is yet to respond to the Commission’s refusal to grant further access to the McKinsey documents.