Burkina Faso’s first militant Islamist group, Ansaroul Islam, has faced setbacks, pointing to the weaknesses of violent extremist organizations lacking deep local support and facing sustained pressure.

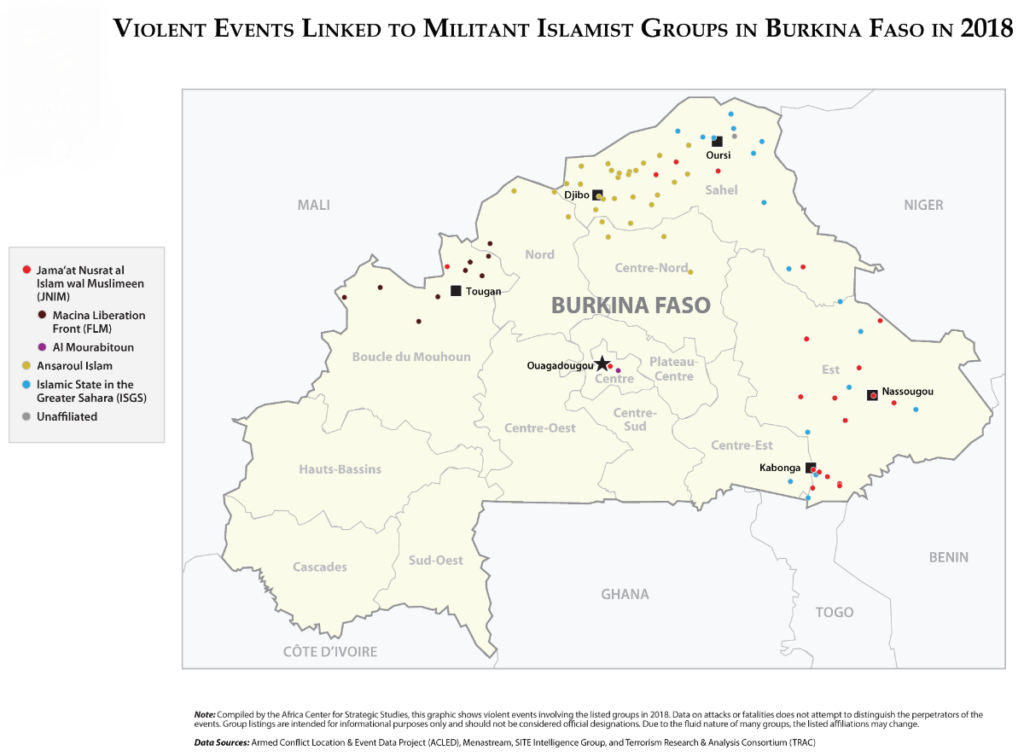

After years of avoiding militant Islamist violence, Burkina Faso has experienced a rapid growth in attacks since 2016. In 2018, there were 137 such violent events involving 149 fatalities. By mid-2019, militant Islamist groups already had outpaced these numbers with 191 episodes of violence and 324 fatalities. Three groups have been primarily responsible—the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), the Macina Liberation Front (FLM) faction of the Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wal Muslimeen (JNIM) coalition, and Ansaroul Islam.

Ansaroul Islam has played an outsized role in the destabilization of northern Burkina Faso. From 2016 to 2018, just over half of militant Islamist violent events in Burkina Faso were attributed to Ansaroul Islam. These attacks were concentrated in the northern province of Soum and clustered around the provincial capital, Djibo. In 2018 alone, Ansaroul Islam led 64 attacks and was responsible for 48 fatalities in this area. Moreover, the group distinguished itself by its propensity to target civilians—55 percent of all of its attacks, the highest percentage of any militant Islamist group in the Sahel (and any group in Africa other than that in northern Mozambique). The violence perpetrated by Ansaroul Islam has forced more than 100,000 to flee their homes and 352 schools to close in Soum alone. Yet by mid-2019, Ansaroul Islam was associated with only 16 violent events and 7 fatalities. This dramatic decline in the group’s activities warrants closer attention. It is particularly important to understand how this militant Islamist group first emerged and what factors have contributed to its diminished role in the first half of 2019.

The Birth of Ansaroul Islam

Ansaroul Islam is considered to be Burkina Faso’s first homegrown militant Islamist group. It was founded in 2016 by Ibrahim Malam Dicko, a Fulani Imam and preacher born in Soum, which shares a border with Mali and today has an estimated population of nearly 500,000 people. Born into a traditional Marabout family, Dicko attended conventional and koranic schools in Burkina and Mali, and went on to teach in Niger as a recognized imam. (His time as a religious teacher in Niger earned him the title “Malam,” a Hausa term from the Arabic mu’allim meaning “teacher” and conveying proficiency in Arabic verse and Islamic texts.) By around 2009, he had returned to Burkina Faso and had started preaching in many villages throughout Soum where he began to develop a group of followers.

Dicko frequently offered his sermons over two local radio stations, La voix du Soum (“The Voice of Soum”) and La radio lutte contre la désertification (“Radio for the Fight against Desertification”). He was a skilled orator who drew large audiences with an anti-establishment discourse that became popular throughout the province. His central messages called for greater equality, for brotherhood, and for challenging the prevailing social order in Soum that he argued disproportionately benefited traditional chiefs and religious leaders at the expense of the general population. As his supporters grew in number, Dicko launched a religious association designed to promote Islam, named al Irchad meaning “guidance” or “the guiding hand” in Arabic. Al Irchad was officially recognized by Burkinabe authorities in 2012.

Around this time, the activities and messages of militant Islamist groups in central and northern Mali captured Dicko’s attention and he sought to engage with these groups. Dicko began meeting and collaborating with Amadou Koufa of the Macina Liberation Front in central Mali. Koufa is believed to have served as a mentor to Dicko.

When Dicko returned to Soum, however, much of the local population, particularly customary chiefs, rebuffed his increasingly radical calls to arms. The rejection of Dicko’s militant and radical message hardened his opposition to customary authorities in Soum. Perhaps recognizing that the local population in Soum would not support violence, Dicko left the province around 2012 to join in the militant Islamist struggle in northern Mali. In 2013, French troops arrested Dicko near Tessalit, in the extreme north of Mali, and he was transported to and detained in Bamako. He was released sometime in 2015 for lack of incriminating evidence, after which he rejoined Koufa, hoping to open a new front of Islamist militancy in Burkina Faso.

In November 2016, after returning to his village in Soum to visit with family, Dicko started mobilizing supporters for the creation of Ansaroul Islam. At this time, Burkinabe security forces had enacted a state of emergency in parts of Soum in search of jihadists from across the Malian border. In the process, security forces humiliated some local elders and traditional chiefs. Dicko exploited these actions to garner support for his militant cause. According to a former member of Ansaroul Islam, the denigrating actions of security forces convinced Dicko and others who joined Ansaroul Islam to stage an attack. In December 2016, Dicko and some 30 armed men attacked a military outpost in Nassoumbou, a village near the Malian border in Soum, killing 12 Burkinabe soldiers. This event is widely considered to be the birth—and first feat of arms—of Ansaroul Islam.

Ansaroul Islam’s Relationship with Local Communities

Ansaroul Islam relies on a narrative of marginalization and grievance to draw support from disgruntled members of local communities. However, its supporters represent a tiny fraction of the overall population. Ansaroul Islam targets state representatives, security and defense forces, and public schools to reinforce its narrative of state abandonment, but it has also targeted civilians in more than half of its activities, suggesting that it never fully gained deep local support.

“Its supporters represent a tiny fraction of the overall population.”While Ansaroul Islam is believed to be predominately Fulani, this is likely a byproduct of regional demographics (Soum is roughly 90 percent Fulani) rather than a concerted strategy to create a specifically Fulani militant group. Instead of appealing to ethnic identity, Dicko sought to tap into local frustrations and a sense of inequality felt by many individuals in the north to establish local support. This message appealed most broadly among those of lower social status, which in Soum consisted primarily of young Fulani herdsmen and Rimaibe (a Fulani caste status indicating a lineage to former Fulani slaves). This may help explain why Ansaroul Islam targeted traditional leaders, and others of a higher social status, who opposed the militant Islamist group’s ideology.

The Apparent Decline of Ansaroul Islam

In May 2017, Ibrahim Malam Dicko reportedly died of thirst and exhaustion after a French-led raid of the militant’s camp in Foulsaré forest. He was replaced by his brother, Jafar Dicko. Known for his brutal temper, Jafar was also influenced by Amadou Koufa. However, Jafar purportedly lacks his brother’s charisma. This change of leadership likely contributed to some degree of internal disorganization and a decline in Ansaroul Islam’s activities. Ansaroul Islam is now estimated to have no more than a few hundred active fighters and a network of informants and logistical supporters located between the villages of Boulkessi and Ndaki in Soum Province.

It is also speculated that a number of militants may have split from Ansaroul Islam, joining FLM or ISGS following Dicko’s death. Both militant Islamist groups are well known in the region and readily employ social media as well as communication tools.

Furthermore, the growing presence of Burkinabe security forces in the northern provinces of the country coupled with the increased operational presence of French military forces under Operation Barkhane in Central Mali likely contributed to a more challenging operational environment for Ansaroul Islam. The French-led Operation Barkhane regularly targets militant groups, including Ansaroul Islam, that hide in Serma and Foulsaré forests in Mali. Moreover, at the request of the Burkinabe government, the French also conducted strikes in Burkina Faso in October 2018. While Burkinabe security forces may have not reestablished control of all parts of Soum, the increased presence of security forces along the Malian and Burkinabe border have complicated the activities of groups like Ansaroul Islam.

Data Sources: Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), Menastream, SITE Intelligence Group, and Terrorism Research & Analysis Consortium (TRAC).

While Ansaroul Islam relied heavily on a narrative of state marginalization and abandonment to appeal to disgruntled members of local communities, it failed to provide services after isolating these communities from the state. Consequently, Ansaroul Islam may have lost its limited support within local communities, particularly following the death of its charismatic leader. The subsequent turn to civilian targets by Ansaroul Islam and insecurity across the region due to armed banditry, further signals that Ansaroul Islam could not count on significant local support. This loss of support coupled with an increasingly challenging operational environment due to the efforts of security forces have likely added to the decline in Ansaroul Islam’s activities in 2019.

A Crisis That Threatens National Cohesion

Burkina Faso has a reputation for moderation, tolerance, and civility, and Burkinabe people are often characterized as a fundamentally optimistic people. In October 2017—a year that had witnessed a steady stream of tragic events and rising violence—55 percent of Burkinabe surveyed declared that their country was going “in the right direction,” according to a study conducted by the Institut Général Tiémoko Marc Garango pour la gouvernance et le développement (IGD) based in Ouagadougou. Yet, this capacity to live in harmony beyond differences, called “vivre ensemble,” is being challenged by the ethnically polarizing actions of militant Islamist groups.

Burkina Faso has a reputation for moderation, tolerance, and civility. … This capacity to live in harmony beyond differences is being challenged by the ethnically polarizing actions of militant Islamist groups.The perceived link between the Fulani community and Ansaroul Islam, for example, has contributed to a push from local populations in the surrounding area to enact vigilante justice. Self-defense militias in predominantly Mossi communities, known as Koglweogo, have increasingly taken justice into their own hands with the rise of militant Islamist groups such as Ansaroul Islam and the insecurity associated with their activities. Koglweogo groups have pursued criminals and bandits, as well as “jihadists,” often inflicting violent punishments, and sometimes attacking innocent people. These militias were blamed for the January 1, 2019, Yirgou massacre in which at least 49 Fulani were killed in a reprisal attack for their alleged association with jihadists.

These types of intercommunal tensions exacerbate the overall security situation in the country and risk further dividing communities that historically coexisted peacefully. Whether part of an intentional strategy or a byproduct of the perceived association of Fulani herders with Ansaroul Islam, the latter has effectively pitted the different communities of Burkina Faso against one another and contributed to a weakening of the country’s national cohesion. The growing threat of intercommunal violence now needs to be addressed by authorities and communal leaders as it risks unraveling the social tolerance that has typified Burkina Faso.

What Are the Responses to This Growing Violence?

In August 2017, prior to the peak of Ansaroul Islam’s activities, the Burkinabe government launched an emergency fund for the Sahel region, including the province of Soum, with roughly $772 million for improving local and administrative governance. In January 2019, then-Prime Minister Paul Kaba Thiéba said the program had already allowed for the creation of numerous schools, hospitals, and roads. He assessed the implementation of the emergency program at around 50 percent, saying $13 million had been disbursed in 2017 and $17 million in 2018. In June 2019, 77 more communes were added to this plan. Such constructive efforts by the Burkinabe government may have helped to undermine local support for Ansaroul Islam by countering their narrative of state marginalization and abandonment.

However, more can be done. Civil society organizations have complained that no arrests have been made after the deadly interethnic clashes that took place in Yirgou at the beginning of 2019. Additionally, Burkina Faso’s armed forces are facing allegations of abuse and extrajudicial killings in several villages, where residents already had been subjected to violence from militant Islamist groups. These alleged crimes, which took place as security forces attempted to respond to the threats posed by Ansaroul Islam, validate the narratives of grievance circulated by militant Islamists. To counter this, security forces and the government will need to collaborate more closely with local populations, recognizing that while many Burkinabe citizens have been victims of militant Islamist activities, they may also distrust the state and its representatives. Working to rebuild trust with local communities by establishing and maintaining a continuing professional security presence is essential to combating the reemergence of Ansaroul Islam or other militant Islamist groups.

It is critical that the government deploy a clear strategy to counter the divisive narratives used by terrorists.It is also critical that the government deploy a clear strategy to counter the divisive narratives used by terrorists. At the end of 2015, the establishment of a national observatory for the prevention and management of communal conflict aimed to foster and facilitate social mediation and the treatment of legal cases. To date, the observatory has had limited impact and has failed to prevent the acceleration of tensions and violence between ethnic groups. This initiative requires renewed government support and resources to promote social mediation and bring communal leaders together to denounce the activities of Ansaroul Islam and other militant Islamist groups.

By working closely with local populations, the government will be able to rebuild trust and further cut support for militant Islamist groups. A concerted and sustained security presence which operates in partnership with local customary and religious leaders can disrupt militant Islamist activities and discourage local support. Rebuilding a positive and sustained government presence in the northern communities devastated by Ansaroul Islam will need to be a paramount objective if the government is to stabilize Soum in the aftermath of Ansaroul Islam’s setbacks.