The dependency theory of development was first come up with a Latin American economist Raul Prebisch, and was centered around the development of third world or underdeveloped countries. It was proposed in the 1950’s and 1960’s, when the underdeveloped state of the global south started being given attention to.

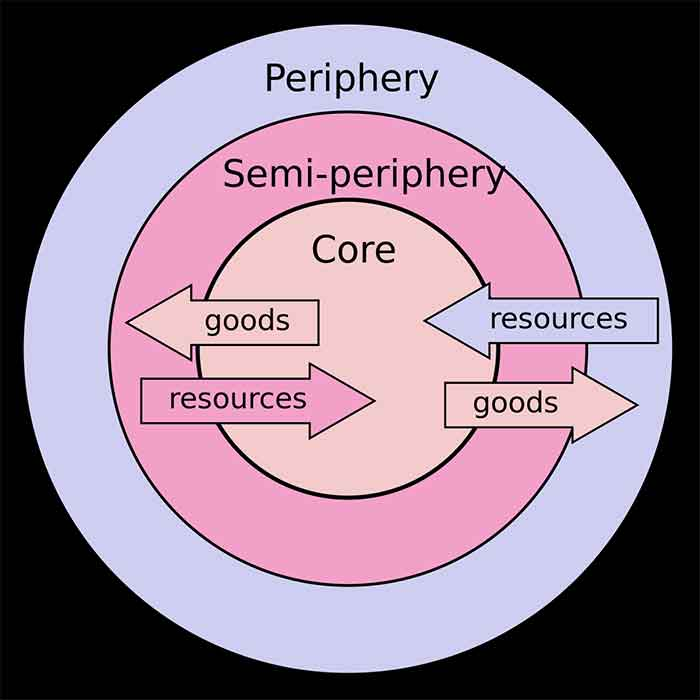

This theory was set out to problematize the Modernization theory, which advocated adoption of modern practices to further development in the underdeveloped countries. The dependency theory stated that the global economic system is divided into the Core (the developed nations) and the Periphery (the Third World), and that there is an unequal dependency between the two. The Core exploits the Peripheral states for cheap labour and resources, and the Peripheral states import the more expensive finished goods from the Core states. Both of these are dependent on each other but this dependency is not mutually beneficial. The Core keeps getting more and more developed while the Periphery will be stuck in a perpetual state of underdevelopment because of the Capitalist model that the global economic system follows, according to this theory. Some theorists suggest that this asymmetrical flow is also mirrored inside the economy of a nation – the urban sector of developing nations is usually more powerful politically and economically, while the rural sector remains underdeveloped and neglected, even though that is where the raw materials and labour is procured from. The solutions to the problem of dependency are provided by two different types of dependency theorists – the ‘moderates’ (such as Raul Prebisch) and the ‘revolutionaries’. The moderates suggest that the developing countries should form blocs and come together to have a more united front so that they have a lesser chance of being blatantly exploited by the Core states. Another suggestion is that the more privileged citizens of the states should invest and revert their funds into the development of their nation. The revolutionaries believe that this is a very idealistic view that is improbable, and call for a more drastic change in the global economic system which is currently based on a very capitalist structure. The “Dependency theory” has been critiqued by many as well, because it assumes that capitalism is the reason for the underdevelopment of nations.

This essay will look at some of the salient features of this theory, first in terms of the impact on the economic growth of the underdeveloped countries which are dependent on the Core, and secondly in terms of heightened inequality in these states, and analyse them using the case study of Taiwan, and conclude by observing whether capitalism is the sole reason for the underdevelopment of peripheral countries.

Taiwan is considered to be a great case for analysing the dependency theory because while it followed the path of being a dependent state, according to studies, the economic impact in the state has not been the way it was predicted by the dependency theorists. Taiwan is a small island that was a colony of Japan from 1895 to 1945, which has interesting implications for its economy. In the 1940s and 1950s, which is the post-War period, the economic condition of the country was not the best, but in the 1960s the economy started booming. During this time, large amounts of foreign investment in the form of aid was flowing into the country from the United States. Taiwan was very dependent on this aid because not many other states were investing in Taiwan. This is the period where Taiwan properly became a dependent state. Its GDP and growth were so good, in fact that while it slowed down during the 1990s and the East Asian Crisis, Taiwan was still ahead of her neighbouring states and managed to pull through the crisis. Early on, Taiwan had adopted an Import Substitution policy, but soon switched to a more dependent policy, which according to the dependency theorists causes ruin to the economy of a developing or under developing country but this was not the case in Taiwan. In fact, the opening up of their economy led to exponential economic growth. After 2001, Taiwan did face a recession, and took a hit during the global financial crisis, which it is still recovering from, but its economic situation as a colonial state and the post-War period is what this essay will focus on in its analysis.

There are many characteristics of the relationship between the dependent state and the dominant state which are highlighted by the dependency theorists. First; Dependent countries are exploited by the Core nations, where their cheap labour and resources are used by the Core nations but the profits of that are not reverted back to the dependent countries for better development and economic growth. In the case of Taiwan, during the colonial period, Japan was following a similar pattern as a Core country would. All the investments made by Japan were mostly to reap all the benefits for itself. However, it is noticed that even though this was the case, there was still a respectable growth rate of Taiwan. During the post-War period, in the 1960s, with all the foreign investment in Taiwan, the dependency theory would assume that all the profits would be accrued by the developed countries, which in this case was the United States (biggest provider of aid in the form of foreign investment). However, this was not the case. A lot of the profit was reverted back to operations on the island, which in turn attracted even more foreign investment into the capital. Even though Taiwan was dependent on the United States, instead of exploitation, it only helped Taiwan further its economic growth.

Second; dependency on foreign investment means that there is a lot of foreign influence in the national economy while the domestic state is weak and not able to fulfil its role as a protectionist state and to further economic development. During the colonial period, while the Japanese had control over most of the operations in Taiwan, they still invested in infrastructure projects such as building railways and dams, etc. and tried to protect the domestic market from international competition. After this, in the post-War period, due to vested political interests, American aid made sure that Taiwan had a strong bureaucracy and military, thus making sure that the domestic government was not weak. In addition to this, the Taiwanese government has invested a lot in improving the agriculture and transportation sector by building on the infrastructure that was initiated by the Japanese government. Taiwan’s industrial growth is owed to encouragement of entrepreneurial projects and good utilization of the foreign investment and aid they received from the United States.

Third; there are two different dependency arguments, one which proposes that due to mass manufacturing the imported goods in the developing countries are cheap and therefore there is more domestic demand for them rather than the more expensive domestic goods, which badly impacts the domestic industry. The other argument proposes that the imported goods are luxury items for which the country has to pay through exports which is not reliable at all and results in using up of the funds which could have been reverted to development of the state instead.

During the colonial period, the Taiwanese domestic industry did not have much scope because of the Japanese goods that flooded the markets, but at the same time Japan created a stable and conducive exports market for Taiwan’s agricultural goods, such as rice and sugar. Therefore, this prediction was not completely accurate during this time. In the post-War period, because of the poor economic conditions of Taiwan, there was not much foreign investment, other than the US aid, so Taiwan was not flooded with imported goods in the first place. Alongside this, labour intensive practices and decentralization of production ensured that the export sector of Taiwan boomed after the 1960s and the international market was a stable one for Taiwanese goods.

Fourth; theorists suggest that dependence on foreign aid leads to a lack of proper domestic capital formation, because the economy is so dependent on foreign aid and investment. There has been a long debate about whether this was the case in Taiwan or not. “Initially, rates of gross domestic capital formation in Taiwan were relatively modest (14% of GNP in the early 1950s), but over time this rate tended to increase, until it reached quite high levels (28% of GNP in the period 1970-73). This change coincided with the phasing out of American aid, which has not been an important factor in capital formation in Taiwan since the mid-1960s. In other words, effective mechanisms for domestic capital formation were developed in spite of massive foreign aid, and these mechanisms made it possible to terminate the aid” (Barrett and Whyte 1982). Therefore, it is obvious that despite the foreign aid received by Taiwan, it still managed to have an impressive gross domestic capital formation.

Through these four characteristics, the impact of dependency on the economic growth of Taiwan was analysed. None of these characteristics prove that Taiwan followed the path that the theorists predict for dependent nations, but a proper conclusion can only be made after analysing the impact of dependency in terms of the inequality in Taiwan, by looking at the characteristics put forward by the theorists.

First; it is predicted that dependency leads to an imbalance in development where there is a favourable advantage to the urban areas of the state. This was not the case in Taiwan. Because the industries in Taiwan were labour intensive and agriculture based, the returns were distributed equally all over the country, because the agriculture sector was the dominant sector of Taiwan. Due to land reforms from 1949 to 1953, agricultural land was more evenly distributed throughout the country, and an increase in population forced citizens to look for non-agricultural work because there was too much pressure put on the land in terms of labour and led to disguised unemployment. As a result, there was less of an income inequality between the rural and urban areas because even people from rural areas started taking non-agricultural jobs, thus leading to more or less equality in the benefits of development all across the country.

Second; in dependent states, the working class is usually more unequal to the employers, there is a lack of labour unions and because of the capital-intensive practices, wages get even lower for the labourers. Taiwan is a special case vis-a-vis this argument because while there are very few labour unions because the government had declared them to be illegal, there has still been decreased inequality in Taiwan. This has been owed to the fact that Taiwanese industries always follow a more labour-intensive method so there are no specific large enclaves. “As with government redistribution, the position of labor in Taiwan leads one to question a tenet of dependency theory: in the Taiwan case, the role of working-class solidarity and trade unions in promoting equality seems less important than the role of the pattern of economic development and its effect on the demand for labor” (Barrett and Whyte 1982).

Third; theorists suggest that due to imported and domestically produced goods flooding the rural markets, many rural people lose their forms of livelihood which were other than agricultural work, thus deepening the income gap between urban and rural settlers. In the case of Taiwan, as aforementioned, in the 1960s, rural people started looking for non-agricultural work, which closed the income gap between agricultural and non-agricultural work, as well as showing a rise in people taking up non-farm work. Therefore, this argument does not work when analysing the economic situation of Taiwan in the post-War period.

Fourth; theorists blame the foreign firms for hiring their own citizens for higher or managerial positions, thus alienating the local workforce from being a part of a middle class. In Taiwan, during the colonial period, this argument was accurate. The Japanese dominated most of the upper and middle class in Taiwan, but in the post-War period, there has been a growth in the country’s middle class owing to the fact that foreign firms have hired local people because of cheap labour which allows these firms to operate at a lower cost.

Therefore, through all these arguments, we have seen that while dependency theorists predict a certain future for every dependent country, this has clearly not been Taiwan’s fate, which is what makes it such an interesting case study to analyse the dependency theory. This leads to the critique of this theory. First, as aforementioned, it states that capitalism is the cause for underdevelopment of countries. While there is no denying that capitalism does give a significant edge and advantage to the already developed countries, a generalized comment cannot be made about the inefficiency of the system, because it does bring prosperity and development to some nation states, Taiwan being one of them. This is tied to the second critique, which talks about how dependency theory does not take into account the political, cultural and economic structures of each individual country. Foreign aid and investment can be a good thing, provided the government reverts those funds into furthering development, instead of making a profit for themselves. This shows that the solutions provided by dependency theorists, which often call for closing up of the economy and opting for an import substitution policy, does not always work. Taiwan is a unique case, and although this essay has proven that every dependent state does not fit the mould that its theorists have created, the country’s fate cannot be decided prematurely. In many cases, the negative effects of the foreign aid show up decades later and there is still a possibility that the negative consequences of Taiwan’s dependency may be evident in the long run. That combined with the dicey future of Taiwanese people due to the Chinese conflict makes it a fascinating yet uncertain case. Regardless of what its future may tell, Taiwan has proven that economies rarely work as one size fits all.