For the last five years, the international community has tried a range of different approaches to mediating the Libyan civil war. All have failed. Most nations and observers not actively fueling the war with weapons, money, training, and mercenaries now see that halting these destructive flows is critical to bringing the rival militia factions to the negotiating table. The Berlin conference slated for February 2020 has the creation of an effective arms embargo as its stated primary goal. However, merely meeting this challenge will not be enough to stem the violence or solve the conflict. Once militias are cut off from external sources of military support, the core economic issues that gave rise to the conflict will still remain. Only a new approach empowering Libyan economic reformers, while reworking the Libyan economic system’s role as a driver of conflict, can fix the dysfunction. To achieve this, international actors need to facilitate and support the establishment of a Libyan-requested, Libyan-led International Financial Commission vested with the requisite authorities to completely restructure the economy.

Abstract

For the last five years, the international community has tried a range of different approaches to mediating the Libyan civil war — sometimes via the UN, while at others via one-off summits convened by major states.1 At different times, these mediation efforts have emphasized political, stakeholder, and security-focused tracks, as well as electoral or population-centric approaches. Most have offered major carrots for success, while some have threatened minor sticks against spoilers. All have failed. Most nations and observers not actively fueling the war with weapons, money, training, and mercenaries now see that halting these destructive flows is critical to bringing the rival militia factions to the negotiating table. The current UN arms embargo is now being openly flouted by several nations to the point that they publicize and hold parliamentary votes on some of their violations.

The Berlin conference slated for February 2020 has the creation of an effective arms embargo as its stated primary goal. As challenging as that will be, it is potentially achievable with concerted diplomacy and the imposition of genuine penalties for violations by the U.S., Britain, and others to dissuade the Emiratis, Egyptians, Turks, Qataris, Sudanese, Chadians, Russians, and others from further meddling. However, merely meeting this challenge will not be enough to stem the violence or solve the conflict. Once militias are cut off from external sources of military support, the core economic issues that gave rise to the conflict will still remain.

Only a new approach empowering Libyan economic reformers, while reworking the Libyan economic system’s role as a driver of conflict, can fix the dysfunction.2 And yet, even courageous and far-sighted Libyan technocrats will not be able to implement the necessary reforms themselves, as long as they are effectively held hostage by the militias that benefit from the current system. International actors need to facilitate and support the establishment of a Libyan-requested, Libyan-led International Financial Commission (IFC) vested with the requisite authorities to completely restructure the economy. This will require including the militia commanders who wield real power in Libya. Such horse-trading with powerbrokers can only succeed in an environment where these commanders are already cut off from the foreign intervention which appears to hold out the promise of allowing them to conquer the entire country without negotiating.

Fortunately, the Berlin conference is already scheduled to include an economic track. Rather than it being relegated to the status of a side show or parallel approach to complement political engagement, the economic track should directly support the immediate priority of securing a functional arms embargo by demonstrating to foreign supporters of all factions that a non-zero-sum solution is possible, and indeed preferable, to their destructive efforts to secure the illusory goal of total power for their favored faction. The most meddlesome foreign powers are often motivated by economic issues including securing payment for old contracts — so the fallacy of zero-sum economic or political thinking drives both the Libyan militias as well as their external backers. Furthermore, properly tying economic reform to conflict resolution can develop momentum for creation of the IFC. Any agreement stopping damaging foreign intervention in Libya is unlikely to hold without a new, constructive mechanism for foreign powers to secure their important economic and security interests in the country via positive-sum mechanisms in a way that would benefit the Libyan people and international stability.

“Future peacemaking efforts, national conferences, or even direct elections are doomed to failure if they do not address the root causes of Libya’s malaise: bad economic incentives and flawed institutions.”

Part 1: Mastering the Problem Set

Diagnosing the Crux of the Problem: In Bullet Points

A New International Approach is Needed

As Libya’s post-Gadhafi chaos has failed to offer up any legitimate social contract to the Libyan people, a perversion of the pre-existing Gadhafian social contract has emerged. Each Libyan region, locality, tribe, ideological grouping, and individual feels that they are as entitled as anyone else to the money and power vested in Libya’s semi-sovereign institutions.3 Communal leaders do not care that the rationales for those institutions no longer exist, they simply want their piece of the pie.

This truth has gradually dawned on most Western policymakers concerned with Libya: the root of the country’s stymied transition and its post-2014 War of Post-Gadhafi Succession4 is primarily economic — not political or ideological.

Future peacemaking efforts, national conferences, or even direct elections are doomed to failure if they do not address the root causes of Libya’s malaise: bad economic incentives and flawed institutions.

The Berlin conference is already poised for failure if it does not provide a coherent approach to treating the economic issues. Yes, there are signs that things are moving in the right direction as a distinct economic track will be included. But this is not sufficient. The economic track must give rise to institutions with permanent engagement in Libya’s economy rather than sporadic engagement via occasional summitry.The Military and International Lay of the Land

General Khalifa Hifter’s April assault on Tripoli has morphed from a spontaneous attack by a rogue general into the world’s first extraterritorial drone war of attrition.5 It is non-Western powers that provide the weapons and technical know-how to keep their clients afloat. The aerial component of the war is being primarily contested between the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Turkey, while the mercenary and training components of that war pit Russia, Egypt, and Sudan against Turkey and Chad.

Turkey has become the backstop of the Government of National Accord (GNA), as the U.S., UK, Italy, and Algeria have apparently rebuffed Prime Minister Fayez al-Serraj’s requests for the necessary military assistance to prevent Tripoli from falling.6 It now appears that if Tripoli is in danger of being taken by Russian-backed mercenaries that Turkey will rush sufficient ground troops to prevent that outcome.

As the war has evolved, European nations have been eclipsed as the most involved international players in the “Libya file,” and hence, German and European attempts to mediate must be backed-up with hard power gambits or they will be brushed off by competitions with military leverage on the ground. In short, too-little too-late re-engagement from Europe without application of uniquely Western forms of leverage will merely showcase the extent to which non-Western countries are the ones now able to project power into Libya, as they can flout UN arms embargoes to provide drones and mercenaries or flout international norms by providing direct injections of cash or illicitly printed dinars.

Western nations, especially if acting in concert, would have a stranglehold on the licit economic tools that are needed to compel both sides to work together and to provide the levers and technical expertise to eliminate the economic drivers of the conflict in Libya.Why Libya Matters and Why Now?

Of the world’s five major conflicts — Ukraine, Syria/Iraq, North Korea, Yemen, and Libya — Libya is the only one whose solution can pay for itself. Solving the Libya conflict would result in an extra million barrels a day of sweet crude, over a hundred billion dollars of yearly spending on mega-projects, employment for a million guest workers, and back-payments in the hundreds of billions.

Moreover, Libya’s continuing cycle of violence and statelessness has created one of the most important hubs for jihadi actors outside of the Levant, while also facilitating arms proliferation, migrant trafficking, and major international crime networks. At present Libya is a major exporter of instability into the Mediterranean and Sahel regional systems. If it were stable with a functional economy, it would be a primary pillar of stability for both.7

For all these reasons, the time has come for America and its closest allies to pivot toward an economic-focused approach to peacemaking in Libya. It is the only avenue which might provide the incentive structures for peace and undercut those for violence. It can be done at either the international community level or by some like-minded countries at the bi- and multi-lateral levels. Britain, Italy, and European institutions must be key to any process.

The upcoming Berlin conference needs to propose a way out of the current impasse which effectuates more than a momentary cease-fire or signing ceremony, but deals with the core of the problem that led to the current war in the first place.

The Economic Angle as a Silver Bullet

To fix the Libyan economy, we must grasp its very essence. The structure of the Gadhafian economy was always an uncoordinated attempt at buying off the country’s different social segments and creating complex vehicles of patronage.8

The Libyan economic system has not been reformed in any meaningful way since the 2011 Uprisings. It needs root and branch economic reform. Having a power sharing arrangement between leaders in Tobruk and Tripoli who have both long overstayed their mandates will not address this issue. Even courageous and far-sighted Libyan technocrats and leaders will not be able to implement the necessary reforms themselves as long as they are effectively held hostage by the militias that benefit from the current system.

Libyan reformers and leaders will, therefore, need to initiate the way forward by calling for the help and assistance of outside technocrats and the power of major international governments and institutions.

Holding elections without fixing the Libyan economy’s unique forms of dysfunction is simply a recipe for intensifying the ongoing war over access to the fonts of corruption, i.e. the Central Bank of Libya (CBL), the Ministry of Finance, the Budget Committee, and the Audit Bureau. Those positions need to be insulated from any military or electoral free-for-all. Moreover, before any short-term pain for long-term gain economic reforms are initiated, the technocratic Western-backed appointees to these crucial positions need to be separated from the political process via the IFC, which can take the heat when unpopular measures need to be implemented.

For economic reform to take hold, international actors can’t just work with existing interlocutors. The problem is that apart from the National Oil Corporation (NOC), all of Libya’s major semi-sovereign economic institutions are as deeply broken and counterproductive as they are entrenched. New interlocutors and a new economic framework must be created by reforming existing institutions. This is the task of the proposed IFC.

By what right can international actors tell Libyans, or guide them, concerning how to reform their economy? One school of thought holds that the international community, and the UN in particular, after the fall of the Gadhafi regime and the failure of a non-interim sovereign government to emerge are effectively obligated to act as in loco regis for the vacant Libyan sovereign (as they did in the period 1947-51 after Italy was forced to abnegate its claims to sovereignty after losing World War II, but before an independent Libyan state was formed).

Rather than holding more rounds of diplomatic conferences and peace negotiations, major regional and international powers need to rally around the establishment of the IFC with its headquarters in either Malta, Tunis, or London.9

Both Russia and Turkey have billions of dollars of contracts with the former regime and in some cases with post-Gadhafi governmental entities. Total loss of those contracts is unacceptable to them, whereas fighting to gain a privileged position to get paid for both old contracts and obtain new ones provides a strong incentive to support a militia coalition they believe can secure these for them. Convincing these outside powers that a stable Libya is actually a win-win will be difficult, but reason supports this argument. Russia, Turkey, and others are far more likely to get some economic benefit from a stable Libya, not controlled exclusively by any given militia coalition, than from a country riven by civil war. The Libyan people, rival outside creditor nations, and international stability will all benefit from the same solution as well.

Libyans need to know that the world is not only interested in them for what they export (crude, arms, migrants, jihadis), but for the domestic well-being of Libyans and the health of the Libyan economy and body politic. Furthermore, in the long run fixing Libya will pay for itself, and the IFC should be funded partially by Libya’s sovereign wealth. Nonetheless, the major powers should be willing to put effort and funds in upfront to show Libyans that this new peacemaking approach “is for real.” This money will be essential to smooth the disruptions and deprivations that will otherwise emerge from the shock therapy of reforms that the Libyan economy needs.“Apart from the National Oil Corporation, all of Libya’s major semi-sovereign economic institutions are as deeply broken and counterproductive as they are entrenched. New interlocutors and a new economic framework must be created by reforming existing institutions.”

Prescribing a Workable Solution in Ten Policy Recommendations

The below recommendations have been formulated in concert with many of the current and former heads of Libya’s most prominent semi-sovereign economic institutions, as well as recently retired senior British and American diplomats who have served in and on Libya. Over the last three years, I have conducted more than 15 such discussions/interviews. I have also discussed these ideas with key members of Libyan civil society and diaspora intellectuals. Courageous Libyans wish to initiate the needed reforms, but lack the help they need to get the ball rolling. The ideas of those participants permeate this paper and constitute the core of the below, “Ten Policy Recommendations to Remove the Economic Drivers of Libya’s Conflict and Set the Country on the Path to Prosperity and Human Capital Development.”

- Establish an IFC with its headquarters in Malta, Tunis or London. It will have offices in Tripoli, Misrata, Sebha, Tobruk, Baida, and Benghazi, but it is essential that its headquarters be outside of Libya so that its Libyan members are not subject to militia intimidation and that top Western officials can easily brief it. To achieve Libyan buy-in, the main Libyan political, economic, and institutional players will initiate the creation of the IFC by requesting it and then formally participating in it — initially by allowing audits of their institutions and other transparency promoting mechanisms. If there is hesitation on behalf of specific relevant Libyan stakeholders to convene the commission, then those who are willing can promote transparency and audits of their institutions, which will build momentum for the full-blown IFC and make it more difficult for spoilers to resist.10

Because optics matter, the international community will not formally request or convene the commission, but rather the Libyan semi-sovereign institutions and top political brass of the rival governments will initiate it — acknowledging that the Libyan economy is dysfunctional and needs the help of Libya’s allies to be reformed. As noted above, the author of this paper has spoken with many of the heads of Libya’s most important semi-sovereign institutions (including the NOC, Libya Post, Telecommunication, and Information Technology Company [LPTIC], CBL, and the Libyan Investment Authority [LIA]); many have assured me that were the right mechanisms in place they would call for such a commission to help them do their jobs more effectively, and that they would want to sit on the IFC, acting as both stakeholders at the commission and reform agents for it. Moreover, the institutions which possess sovereign wealth (LPTIC, CBL, LIA, and its subsidiary the Libyan Local Investment & Development Fund [LLIDF]) would be willing to fund the IFC’s activities if it brought increased Western engagement, capacity building, and protection of their institutions from militia intimidation.

This paper has made clear that an IFC is necessary to undo the corrupt incentive structures that operate at present. A genuine supra-national commission with sovereign powers to reform the institutions of the Libyan economy is needed. The 1876 Anglo-French Casse de la Dette Publique in Khedival Egypt should be a loose conceptual model (upgraded to 21st century and Libyan sensitivities, of course) of how an international commission can have both supervisory, administrative, and oversight powers over an entire economy and adjudicate claims from competing sovereign and corporate creditors. International technical experts embedded in the Libyan ministries won’t work — as, in Libya, the ministries have relatively little power and their functions are duplicated at the semi-sovereign institutional level. The process of embedding technical experts without country-specific expertise was tried and failed after the ouster of Gadhafi. The IFC will differentiate itself from previous training experiments by having Libyans and Western experts of Libya as its core components. Libya is too complicated for outsiders — other than those that have dedicated a significant portion of their professional lives — to fix it.

The IFC will start by cataloguing and auditing the Libyan economy — financial and petrol flows as well as subsidies, institutional architectures, debts to foreign companies, and the competences of various authorities. Only once the research is done and the findings promulgated will the IFC engage in the action phase of announcing and implementing reforms. It should have an equal number of voting members from Libya and from the key international and regional powers. The chairmanship should rotate among a Libyan, a Briton, an EU official, and an American.

At present only internationals have the capacity to devise the technical mechanisms needed to fix the Libyan economy in a transparent way. Mid-career officials from the foreign ministries must also staff the commission, not only technical experts. This is essentially to signal the political will from, and the direct connection to, the key policy makers back in London, Brussels, Rome, and Washington to vest the commission with the requisite political clout and power.

- The first act of the commission will be the creation of a website — with easy access via social media and the internet — that can communicate the actions of the IFC to Libyans and worldwide in Arabic and English.

Libya has one of the highest rates of social media and Facebook penetration in the world and its citizens are highly involved in the country’s political discourse. To date this has been a point of polarization; it can equally be wielded as a point of inclusion. Libyans should be able to easily submit evidence to the commission via an online platform.

- After the website is operational the second step of the commission should be to figure out how Libya’s economy actually works at present. It will hire academic experts and retired Libyan and international businesspeople and diplomats to create a map of Libya’s economy and its stakeholders. This work will demonstrate the formal and informal power relationships and existing laws that constitute the architecture of Libya’s economy and institutions. Its findings will be published on the web in Arabic and English for all to see.

This will facilitate domestic Libyan buy-in for the proposed reforms.11 Unlike in other societies, Libyans do not have a constitution, fundamental law, or monarchical charter which explains how power flows in their society. The Libyan people are educated, involved, and deeply curious. The IFC must not engage in spin or propaganda. It must simply present the facts as verified by experts. This step will create enormous goodwill for the IFC and allow for a conversation with the Libyan people in a way that previous attempts at National Dialogue have not.

- Create a system to transparently monitor flows of refined petrol.

A GPS tagging system for petrol trucks and a special website which allows for tracking the movement of petrol across the country in real time should be established. All petrol for the Libyan domestic market can be tagged with a special compound so that it can be traced if it is smuggled abroad. The NOC has recommended this step previously.12

- Create a system to transparently monitor financial transfers into and out of the CBL and into and out of ministries. At present, only the functionaries of the rival branches of the CBL and military leaders know how the Libyan economy truly functions. Top officials in the GNA and interim Baida-based government are unaware of how various sums are spent.

Complete transparency of allocation of money to ministries and municipalities must be achieved immediately. It must also be clear what they spend it on. The results should be published online in Arabic and English. Corruption has thrived in the dark and will be progressively minimized by the light. The CBL is not solely to blame for the current state of affairs; it is a result of the Gadhafian legacy. However, without the CBL’s buy-in this plan cannot be implemented.

- Complete an audit of Libya’s semi-sovereign economic institutions. Make the resulting document of “who has what and where” public for all Libyans.

- Achieve buy-in from the Libyan people about what a “fair and just” Libyan economy would look like by conducing social media and telephone polls, culminating in a national conference on the topic.

- Undertake subsidy reform, currency devaluation, then flotation. The plans should first be promulgated and then implemented.

- The laws governing Libya’s semi-sovereign institutions should be re-written by the IFC and then implemented by those very institutions in concert with relevant government authorities.

- New technocrats — especially young people and women — should be chosen via a meritocratic process and installed within the reformed institutions. They should receive ongoing training and communication from the IFC as they reshape the Libyan economy.

“Libyans are fighting over preferential access to the institutions that wield economic power, and foreign actors are supporting those sides that they perceive will secure their preferential ability to secure back-payments, lucrative contracts, and ideological allies.”

Part 2: Background, Sovereignty, Timing, and Leverage

What is the Current War for Tripoli Really About?

Since its inception in April 2019, the battle for Tripoli, or what I have termed elsewhere the Second War for Post-Gadhafi Secession,13 has essentially led to a stalemate. General Hifter’s attempts to use the so-called Libyan National Army (LNA) to conquer Tripoli via a blitzkrieg without massive external support were never credible and they were eliminated by the retaking of Gharyan in June 2019.14 Now Hifter’s attempts to take Tripoli via attrition in the wake of the “zero-hour” assault announced in December 2019 rely largely on Emirati airpower and Russian, Sudanese, and Egyptian mercenaries and trainers. This is not to say that the anti-LNA or pro-GNA side is doing any better — its ranks are riven by dissension and many groups allied with it have not dedicated most of their fighting strength to the battle. Were the anti-LNA coalition not propped up by Turkish support and a lopsided reliance on Misrata’s battle-hardened militiamen, Tripoli would have long ago fallen.15

On Jan. 2, 2020, Turkey’s parliament approved a bill to enable Turkish troops or mercenaries to be deployed to Libya to support the GNA. This is the first time that a foreign country has overtly stated its commitment to sustained military intervention in Libya’s civil war. In response, the LNA launched a pre-emptive, and largely successful, invasion of Sirte on Jan. 6, 2020 — fearing that any upcoming increase in Turkish mercenaries, logistics, and airpower would tip the battle throughout the country against them. The LNA’s recent capture of Sirte is the most significant development in their campaign to conquer Tripoli, both strategically and symbolically, since their devastating loss of Ghariyan in mid-2019. Moving forward, in an attempt to gain a leg up and in the absence of any concrete international pushback for the overt introduction of foreign forces, we can expect to see the near complete foreign penetration of the strategic and operational aspects of both warring coalitions — leading to the further protraction of the battle on the ground.

If history is any guide, the more protracted the battle becomes, the more this favors Hifter. The anti-LNA coalition’s unity is quite tenuous, while Hifter has proved in his prior conquests of Derna and Benghazi that he is willing to play the long game.16

Hifter has long grasped that the economic semi-sovereign institutions17 are fundamentally at the core of any political/military struggle.18 He made the departure of Central Bank Governor Sadiq al-Kabir his rallying cry when he took over the oil crescent ports in June 2018. Yet Kabir remains in place despite overstaying his mandate as CBL governor by many years. He remains in a situation where according to the Skhirat Agreement the Higher State Council head Khaled Mishri could in theory simply agree with the House of Representatives’ appointment of Mohamed el-Shukry and push him out the door.

The current quest to take Tripoli was arguably a last-ditch attempt to control the Central Bank and was well underway before the April 4 assault began.19 Prior attempts to leverage control of Libya’s oil crescent to achieve influence over CBL policy did not work.20

An insider present at the March 2019 Abu Dhabi meeting between Serraj and Hifter, where they shook hands and supposedly “agreed” on joint resolutions, told the author that Hifter appears to have speculated that the Abu Dhabi understandings set to be enshrined in the National Conference scheduled for April 14 would eventually prove not satisfactory to him, if they still left Libya’s economic institutions beyond his grasp. Hifter was set to achieve a modicum of political and military power over Libya through this agreement and the ensuing National Conference process. Moreover, if he had advocated for elections and made various minor compromises to secure them, he would likely have been able to be elected president. However, absent a proposed restructuring of Libya’s economic institutions, he chose violence over any of those political gains.

Those motivations for continued fighting likely still animate senior LNA command. As the war’s evident stalemate draws in more regional powers seeking to secure their interests in Libya,21 key interlocutors (UN, EU, UK, and U.S.) need to help propose a way out of the current impasse that is not just a momentary cease-fire, but deals with the core of the problem that led to the war in the first place. For any compromise to last it must address the real drivers of the conflict. Paradoxically, if the IFC can be framed as bringing economic justice to marginalized communities like those in the east and the oil producing regions, it could be accepted by both LNA top brass and certain cadre of their key social and tribal supporters.

The Skhirat Agreement failed because it was politically focused and put the main economic issues into a deep freeze, while incentivizing incumbents to oppose reform — allowing the economic drivers of conflict that led to the militia problem, the smuggling problem, the semi-sovereign institution problem, and the jihadi problem all to persist untouched.22

What we can gather from the above is that Libyans are fighting over preferential access to the institutions that wield economic power, and foreign actors are supporting those sides that they perceive will secure their preferential ability to secure back-payments, lucrative contracts, and ideological allies. This is not simply a fight for control of oil installations or the CBL’s headquarters. The fight is as complex as the Libyan economy itself.

The Libyan economic system is not a straightforward rentier system where a disenfranchised populace is paid off in subventions, salaries, and welfare perks to remain quiescent. Yes, Libya has aspects of all of those elements. Nonetheless, it is not a rationally constructed welfare state, like those of the Gulf monarchies, where according to clearly defined rules the populace gets handouts from the government and various elites receive opportunities to enrich themselves within clear parameters.

As I have written elsewhere,23 the precise complexities of the Libyan economy need to be studied by specialists, yet to generate the requisite information, the international community needs to summon the political will to advocate for — and incentivize — transparency. Only then can the resulting knowledge be used to undo conflict drivers. The ideal approach would be for major Libyan stakeholders on both sides of the political divide and in both branches of divided institutions to call for international assistance and arbitration via an international financial commission to eliminate the drivers of conflict. This would represent one way of “completing” the unfinished revolutionary process that Libyans are still fighting to shape according to their factions’ desires. Opponents of this “national process with international support approach” would say that decentralization is a better way to undo the Libyan economy’s perverse incentive structures.24 I contend that the IFC-reformed Libyan economy will likely be more decentralized in its structures, with the vast majority of oil revenues dispersed and expended at the local level.25 Yet, a national process with international support is needed to create these more decentralized structures.

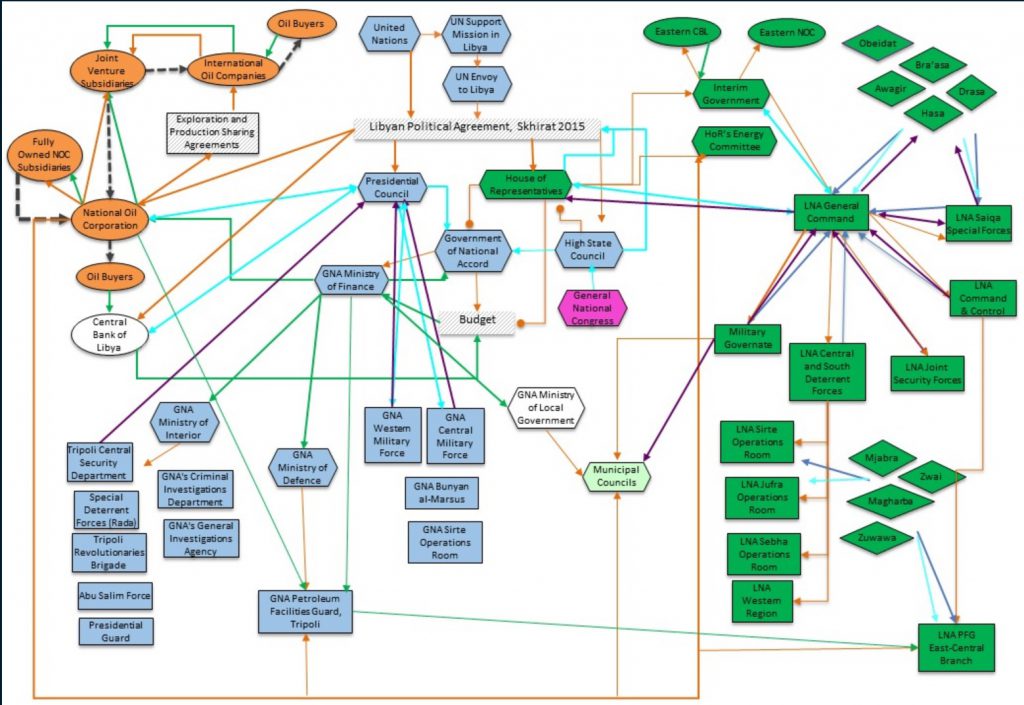

Figure 2 | Economic institutional and stakeholder relationship mapping post-Skhirat Agreement

2011 Was Not a Revolution: That is Why the Economic Fabric of the Ancien Regime (the Semi-Sovereign Institutions) Survived

What happened in 2011 was merely a series of disconnected uprisings.26 A genuine root and branch revolution (like France in 1789 or Russia in 1917 or the Warsaw Pact Countries in 1989) would have destroyed entities like the Economic and Social Development Fund (ESDF), the Organization for the Development of Administrative Centers (ODAC), CBL, and LIA — expropriating their monies, replacing them with more functional or more “revolutionary” institutions answerable to the new regime’s logic, and doling out funds at the behest of the new order. Tsarist Russian institutions were destroyed, their liabilities or hard currency either erased or ransacked by new structures. The same happened with the fall of the Soviet Union.

Yet in Libya, due to the absence of genuine leadership or a unifying vision of what post-Gadhafi Libya should look like, the multibillion-dollar behemoths are all still intact. Salaries and subsidies have been raised on multiple occasions, yet the mechanisms and institutional logic of using oil revenues and extreme centralization to buy off the Libyan people’s complacency was never altered. Today, the General Electric Company of Libya (GECOL) and the LIA, as examples, appear as much facts of Libyan life as the Sahara Desert — immutable and eternal, filled with vast economic resources and huge opportunities for inefficiencies, smuggling, and self-dealing.27 Due to their perceived permanence and prestige, there is an incentive for Libyans to fight to control these loci of power.

Paradoxically since 2014, as the rival governments’ abilities to govern or control territory have been steadily weakened, they still fight tooth and nail over the right to officially run Libya’s semi-sovereign economic institutions. In fact, their legal “rights” to appoint boards of directors of institutions or award access to contracting vehicles are the only real powers that either government possesses. In short, in a country where no government holds genuine sovereignty, it is these semi-sovereign economic institutions that (in certain instances) are the only functioning parts of the Libyan “state.” They have more than merely cash — they are still vested with power and legitimacy, where the governments’ ministries are not.

It follows then that as Libya’s post-Gadhafi chaos has failed to offer up any legitimate social contract to the Libyan people, a perversion of the existing Gadhafian social contract has emerged. Each Libyan region, locality, tribe, ideological grouping, and individual feels that they are as entitled as anyone else to the money and power vested in Libya’s semi-sovereign institutions. People do not care that the rationales for those institutions no longer exist, they simply want their piece of the pie. And they are willing to fight for it.

“Today, GECOL and the LIA, as examples, appear as much facts of Libyan life as the Sahara Desert — immutable and eternal, filled with vast economic resources and huge opportunities for inefficiencies, smuggling, and self-dealing.”

Is the International Community Sovereign or Partially Sovereign in Libya?

Why should the international community have any role or legitimacy in remaking Libya’s economic structures and complete the trajectory of the anti-Gadhafi uprisings?

Firstly, because since 2014, the Libyan conflict has become a penetrated system whereby the armed actors and institutional heads function primarily due to the support or legitimacy that international actors bestow upon them. Secondly, my historical and legal research has postulated28 that Libyan institutions were semi-independent under Gadhafi, developed semi-sovereignty in the political vacuum in the wake of Gadhafi’s ouster, and via the Skhirat treaty process international stakeholders have granted them a claim to complete sovereignty.29 In short, the “sovereignty” of the CBL or the Housing and Infrastructure Board (HIB) — in as much as they exist — has been granted by the UN and international actors and not by Libyan law. The reason for this is twofold: firstly, these institutions are merely shells from the Gadhafi period and it is international actors’ willingness to accept them as legitimate that has enshrined them in the Libyan scene, and secondly, since 2014, Libya has lacked a sovereign authority.30 Rather than using its position of authority to undo this institutional morass, much of international policy since 2014 has sought to insulate the CBL, LIA, Audit Bureau, and the NOC from the civil war and from partisan meddling, as if they were true sovereigns in line with their designation in the Skhirat Agreement.31 In fact, as I have demonstrated elsewhere the UN mediation process overtly granted sovereignty to Libya’s economic institutions to make sure that the diplomatic and business communities have interlocutors to deal with.32

As it pertains to the NOC this was possibly a noble and necessary goal to prevent complete financial and humanitarian ruin, but in the case of the CBL, ODAC, GECOL, HIB, and others, this attempt merely froze the structures of the Libyan economy in their status quo ante positions without helping to create the political environment needed to give these institutions coherent economic functions. Its implication was to fix in place a form of dysfunctional centralization and hence lead to cycles of violence to control Tripoli — where the institutional headquarters of these bodies are based. Inherently, decentralization must be a part of any reform process.

By issuing protections to status quo ante institutions, the international community has treated these institutions as if they truly operated in a vacuum of governance and sovereignty and hence had become completely sovereign entities. The wording chosen in the Skhirat Agreement text in 2015 actually accords with the UN Support Mission in Libya’s and major international players’ ensuing actions. This wording and complimentary political actions defy both reason and facts. The key, therefore, to untying the tangled knot of the Libyan crisis lies in acknowledging the semi-sovereign status of the country’s economic agencies, and hence, their accountability to both the Libyan people and subordination to the international institutions and treaties from which Libyan sovereignty derives. This legal realization gives the legitimacy for key Libyan stakeholders and their international allies to call for the creation of the IFC.

Some might argue it could be brought into being even without comprehensive Libyan buy-in, as there would likely be various incumbents and status quo powers that would fear the loss of sovereignty that any reform would occasion. One school of thought holds that after the fall of the Gadhafi regime and the failure of a non-interim sovereign government to emerge within the time limits set out by the Aug. 3, 2011 temporary constitutional declaration, the international community, and the UN in particular, became effectively obligated to act as in loco regis for the vacant Libyan sovereign (as they did in the period 1947-51 after Italy chose/was compelled to abnegate its claims to sovereignty after losing World War II, but before independent Libya was formed).33 Seen from this legal perspective, the international community and the UN might have both the right and the duty to exert their sovereignty and either dismantle or reform the alphabet soup of semi-sovereign dysfunction. In the eyes of most Libyans, the institutions created in the Gadhafi period (e.g. ODAC, HIB, LIA, GECOL, LPTIC, ESDF, etc.) are as illegitimate as the pots of money squirrelled away by Gadhafi cronies offshore, frequently by using the semi-independent prerogatives of these institutions.34 If international recognition of GECOL, the CBL, or the LIA was suspended or assets frozen (as it has been done at various times), it would then become sanctionable for multinational companies to work with these entities. This would create exactly the requisite necessity for key stakeholders to call for an international commission.35

“Libyan institutions were semi-independent under Gadhafi, developed semi-sovereignty in the political vacuum in the wake of Gadhafi’s ouster, and via the Skhirat treaty process international stakeholders have granted them a claim to complete sovereignty.”

Which International Powers Have the Legitimacy, Neutrality, Technical Expertise, and Know-How to Help Catalyze and Support a Libyan-led Economic Reform Process?

The answer comes into focus if we use the process of elimination. Only the U.S. and the UK36 are candidates for the role of convener of a Libyan-led IFC. The French, Italians, Russians, Saudis, Jordanians, Qataris, Turks, Emiratis, and Egyptians are all perceived as too biased toward one side or another. The rest of the European and regional powers are simply not powerful enough (to punish spoilers and encourage transparency) or not interested enough to be able to make a difference on their own, but can fulfil the role of gadfly (as the Germans are doing), hosts (as the Moroccans and Tunisians have done in the past and will in the future), or funders and implementers of specific technical and humanitarian assistance (as the Swiss, Dutch, and Scandinavians have done over the years).

The Franco-Italian feud over Libya has long been out in the open — and for the past few years it has prevented the formation of a unified Western front toward Libya. Its geopolitical components are well known: the French focus on counter-terror as opposed to the Italian focus on stopping migration. For each nation, Libya has become a more salient trope in domestic politics for the embattled leaders: the Gaullist rhetorical need for a strong French leader like Emmanuel Macron to “lead from the front on North African” issues, while the neo-populist Italian prime minister, Giuseppe Conte, also needs to demonstrate a hardnosed approach toward migration.

The economic drivers of this rivalry are less discussed. Both sides’ major oil companies have increased their holdings over the last three years and remain the only Western majors willing to put significant capital investment into Libya.37 France wishes to become the economic superpower of the entire Mediterranean and Italy wants to avoid losing the only foreign market where its companies retain a preponderance of power. Although France’s GDP is only 25 percent greater than Italy’s, its geopolitical leverage on foreign policy issues is many orders of magnitude greater than Italy’s. This imbalance fuels the animosity. As this feud is likely to escalate, attempts to reform the Libyan economy cannot be made prisoner to the zero-sum logic of feuding foreign powers, nor can they be associated in the Libyan mind with that type of old school colonial policy logic. France and Italy must be included in any IFC process, but they must be outside supporters rather than active participants.

Since 2011, the U.S. has established itself as the convener of a series of occasional neutral-venue meetings called the “Libyan Economic Dialogue.” These meetings bring together the main Libyan economic officials (e.g. rival heads of semi-sovereign institutions as well as relevant politicians and ministers). This process has been the sole coherent external impetus for institutional unification and reform, and progress has been slight. As stated in the introduction, the UN and the great powers have mostly invested their efforts in counter-terror, political mediation, and migration issues. At the 8th Economic Dialogue meeting on June 5, 2018 plans to cut fuel subsidies and effectuate an indirect devaluation of the dinar via taxes on letters of credit (LCs) were announced.38 The ensuing taxation on foreign currency transactions did result in some modest successes when it was first implemented in the fall of 2018 by narrowing the gap between black market and official rates of exchange for the Libyan dinar. But implementation became bogged down in November 2018 as backlogs at customs at many ports led to stoppages at Khoms in particular and the announcement of a grace period on the LC tax implementation until 2019. In 2019, the surcharge on LCs (which functions as a foreign exchange tax) had been successful in keeping the dinar strong and decimating the black market, but those successes have lessened the willpower of the status quo party (major political figures in the GNA along with the CBL governor) to undertake the major structural reforms that are truly needed. The status quo party has defeated the economic dialogue process by doing just enough to avert sufficient American or domestic pressure to remove them.

In short, the economic dialogue process has proved incapable of fostering the political will among Libyans for root-and-branch reforms or delivering Libyans the technical/economic expertise needed for the implementation of big picture changes. In a way, the economic dialogue process has acted as a fig leaf covering up the status quo party’s insistence on thwarting reform.

“Various recent appointments and promotions within the U.S. government during 2019 and the pending bipartisan congressional legislation entitled the 2019 Libyan Stabilization Act finally make it feasible that increased American political resources could be devoted to an expanded process of engagement in Libya.”

Part 3: Timing, Leverage, and Avoiding Pitfalls

Now is the Right Time for Anglo-American Leadership

The framework of the American-led Economic Dialogue needs to be built upon and transformed. Various recent appointments and promotions within the U.S. government during 2019 (especially the bipartisan appointment of the former ambassador to the Republic of Georgia, Richard Norland, as the first U.S. ambassador to Libya to be confirmed during the Trump administration as well as longtime Libya hands Natalie Baker as the deputy assistant secretary of state for Maghreb affairs and Lauren Barr as director for North Africa at the National Security Council) and the pending bipartisan congressional legislation entitled the 2019 Libyan Stabilization Act39 finally make it feasible that increased American political resources could be devoted to an expanded process of engagement in Libya. Once passed, the congressional legislation not only allows for a broad array of sanctions, but makes it possible to revisit the question of a presidential (rather than a State Department) special envoy — an appointment which would then underpin the coordination of the interagency process among the Departments of Treasury, Commerce, Energy, and State which would be crucial for coherent U.S. leadership of the IFC process.40

On the other side of the Atlantic, Boris Johnson’s resounding victory in the Dec. 12, 2019 parliamentary elections means that Britain will finally be able to invest political capital into questions other than Brexit. Johnson showed a significant interest in Libya as foreign minister; during his tenure, he visited Tripoli in May and again in August 2017 as well as Tobruk, Misrata, and Benghazi.41 This means that other than the Italians or the Maltese, he was the most personally involved of the Western foreign ministers during that period.

Johnson’s sustained personal interest, engagement, and intimate knowledge of the key players of the conflict could lead to a bold British re-engagement after nearly three years of dormancy on the Libya file. There is also the fact that that period of dormancy coincided with the lead up to the current round of civil war, meaning that Britain has remained relatively neutral, unlike the non-Anglo-Saxon P5 members. This perception of relatively neutrality combined with the ongoing pen-holding role at the UN, is also significant to jump start the proposed IFC process or to build on the Berlin Process in any other direction. It is also worth noting from a personnel standpoint, Martin Reynolds, HM ambassador to Libya for a brief period in the spring of 2019, was previously Johnson’s personal private secretary when he was foreign minister. Now it appears that Reynolds will continue serving as something equivalent to a national security advisor within Downing Street. Reynold’s experience and access to the Cabinet puts him in the perfect position to occasionally foster political will and undertake interagency coordination on the British side for the IFC implementation process.

Working together and drawing on these increased capacities, the U.S. and UK could get the ball rolling with various proposals at the Berlin Conference, then support key Libyan interlocutors, hold major players’ feet to the fire, and initiate the IFC process at the UN through Britain’s pen-holding position.42 The rhetoric and actions at the early stage should all focus on increasing transparency and facilitating buy-in for a Libyan-led process. British expertise in central banking and the fact that so many Libyan financial institutions (LIA, Bank ABC) have offices and funds in London gives the UK unique and heretofore unused leverage. Working with the U.S., which controls the SWIFT system and has been activist on sanctions in other conflict zones over the past few years, the two powers can be invited by key Libyan stakeholders to create and co-chair the IFC on Libya.

This IFC formation and implementation process should be entirely separate from the ongoing German, French, Italian, and larger UN political mediation processes toward Libya. Rather than creating a new competing international initiative, such a step would bring clarity to the four different tracks needed to address Libya’s interlocking crisis. In fact, it would create a coherent system where each of these tracks could be led by one or two of the major four Western powers involved in Libya: the paramount IFC led by Britain and America, the maritime/migration track by Italy and the EU, the political/elections track by the UN and France, and the counter-terror track by America and France. This would be supplemented by the UN, which would be solely in charge of restarting the national conference and constitutional tracks and in involving the Libyan populace in the various efforts to help them. To achieve buy-in from the powerful non-Western parties with interests in Libya (especially the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey, Russia, Egypt, Algeria, and Tunisia), they must be present at the table and given important secondary positions in each of the tracks that affects their interests, while the choice of Western leadership should be presented as a mechanism to insulate the process from regional rivalries while achieving maximum leverage and technical expertise. One could imagine Egypt and Algeria playing a key role in the counter-terror track, while Tunisia would be essential in the maritime/migration track, and Russia, Turkey, and the UAE would have a special seat at the table in the economic track.

Of all these tracks, the economic track must have primacy and animate a new approach toward the other tracks. Economic dysfunction, smuggling, and corruption are the genuine root causes of Libya’s problems; migration, political stalemate, and spread of jihadism are only symptoms. Hence, initiating economic reforms is far more important than elections, cease-fires, or high-level political deals, as it is the economics of the country that lead to fuel smuggling, human trafficking, and the kind of corruption that allows for militia dominance and fuels civil war.43

Of course, eager Libyan reformers are afraid that they will face blowback from militias whose interests are harmed by such reforms. Hence, those commanders will have to be included from the outset. Understanding that no more outside military assistance will be forthcoming and knowing from experience that they cannot conquer the whole country without it, militia leaders will be under increasing pressure to provide domestic economic opportunities for their supporters. Such employment and economic growth can only be built on stability as long as Libya’s fortunes depend on international financial institutions. Courageous Libyan reformers, NGO leaders, and civil society figures will need support and encouragement. Such support and pressure are best offered multilaterally and applied at arm’s length via a neutral body like an international commission, rather than bilaterally, which has tended to fuel the current civil war.

“The UN and most Western nations have relied on press releases and diplomatic carrots, while the regional powers, which support spoilers, have deployed hard power in the forms of arms, mercenaries, and cash. This trend has become exacerbated in the current battle for Tripoli.”

Leverage and How to Deploy It

Prior international attempts to help in Libya’s post-uprisings reconstruction (2012-13), to avert civil war and the fracturing of the county’s institutions (2014), to reunify those institutions and create a pathway to elections (2015-18), and to halt the offensive against Tripoli (2019) have all failed because the international community has not deployed the leverage or goodwill that it possesses effectively. The UN and most Western nations have relied on press releases and diplomatic carrots, while the regional powers, which support spoilers, have deployed hard power in the forms of arms, mercenaries, and cash. This trend has become exacerbated in the current battle for Tripoli.

Western nations must finally threaten to use their stranglehold on international economic institutions and transactions to force Libyans to the table and to penalize outside actors that offer perverse incentives to militia leaders. The easiest Western leverage to deploy is on Western “allies” like the UAE or Turkey. The Berlin conference’s express purpose is to propose concrete penalties to those nations which violate the UN arms embargo by supplying drones and mercenaries. Once the Libyan armed factions lose their most important foreign backing, then a mutually hurting stalemate will likely take hold.

Simultaneously, genuine naming, shaming, and sanctioning of spoilers must be applied multi-laterally and comprehensively against all sides. There must be no picking of favorites. Recent UN Sanctions Committee reports and U.S. congressional legislation provide the information and the teeth to do this. The U.S. and UK are viewed on the ground as relatively neutral actors, even if the UN is not. With these sticks in place, even previously recalcitrant Libyan technocrats might prove quite eager to participate in the IFC. Once they express that willingness, they need to be protected. Spoilers who benefit from the status quo war economy will likely attempt to hijack the process. They will be unable to do so if foreign support to such spoilers is profoundly penalized and boxed out and key militia leaders involved in Libya’s economy and willing to participate are given a real seat at the table, rather than being treated as elephants in the room, as in previous negotiation processes.

“Financially and diplomatically, Libya’s civil war is among the most complex and globalized of the 21st century’s major conflicts. As such, international policy must finally come to reflect the reality that the devil is in the details.”

Conclusion: Avoiding Another “Oil-For-Food” Fiasco by Having a Genuine Libyan-led Process

Financially and diplomatically, Libya’s civil war is among the most complex and globalized of the 21st century’s major conflicts. As such, international policy must finally come to reflect the reality that the devil is in the details. No one actor can dominate the country. No single military or political event can cut the Gordian knot of corruption and bad incentives. It is for this reason that the conditions that allow this mess to persist must be studied in depth and untangled bit by bit — by diagnosing drivers of conflict and chokepoints to progress and then systematically eliminating them. The easiest such drivers to eliminate are subsidies, the dinar rate, and the blocking power of vested economic players who allow the current morass to persist.44 Once those are out of the way another layer of spoilers, militia chokepoints, and command and control blockages will need to be dealt with. The IFC process can achieve the requisite degree of specificity, research, implementation, and pooling of political will.

Britain and America must lead the efforts (giving personnel, operating budgets for international staff, and precious executive will) to establish the IFC, to protect the courageous Libyan stakeholders keen to work with the IFC from militia violence, and push the international community and the Libyans to reform the country’s macroeconomic structures. The approach outlined in this paper will not be easy and it will face difficulties of implementation, perception, domestic buy-in, and of major international players’ political will. Nonetheless, as the author’s interviews have made clear, it is the only model that Libyan stakeholders and retired senior Western diplomats believe has any chance of success. It can be framed as a consensus international approach to dealing with Libya’s ongoing civil war deriving from Libyan political leaders and semi-sovereign institutional heads, who will request it and facilitate buy-in and transparency.

For the IFC to work, lessons must be learned from the Iraq “Oil for Food” debacle, which scarred a generation of UN and P5 diplomats. The main lesson which must be applied to Libya — as told to the author by retired diplomatic participants — is to focus on transparency (both of financial flows and of decision criteria) while having Libyan institutions and stakeholders call for the IFC rather than having UN fiat decree it upon them. Fortunately, top Libyan political and economic officials frequently request increased U.S. and UK engagement in their country and have stated in London and Washington that they are willing to publicly request more engagement. Moreover, relative to Iraq in the 1990s, the current information technology and its broad penetration in Libya means that transparency is arguably easier now than it was at the time of “Oil for Food.” Today, it is possible to engage in diplomacy directly with the Libyan people by publishing in real time the workings of the commission on the internet and social media and making the reformation of the Libyan economy a collective nation-building project.

Libya is filled with economic opportunities. At present these economic assets and the economic needs of the Libyan people are being used to enable corruption. These assets and needs can be turned into even greater opportunities to release the productive capacity of the Libyan people and to connect Libya with the Western private sector for skills transfer. This can only be accomplished if a neutral caretaking technocratic commission creates new institutions and agrees on the rules of the economic game prior to the free-for-all power grab of elections or jockeying for position in a post-civil war appointed government.