Being Ready Is the Best Way to Prevent a Fight With China

Why isn’t the United States doing more to prepare for war with China over Taiwan—precisely to deter and thus avoid it? The visit to Taiwan this month by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Beijing’s dramatic response to it have crystallized the gravity of this issue. A war with China over Taiwan has gone from what many regarded as a remote scenario to a fearfully plausible one.

Yet the disquieting reality is that the United States does not appear to be adequately preparing for such a conflict despite a strengthening commitment, especially by the Biden administration, to the island and its autonomy. Given its public statements and strategies, it would make sense for Washington to be behaving as though the United States might well be on the verge of major war with a nuclear-armed superpower rival. But although the administration may be making moves in the right direction, the changes it has made so far appear to be unequal to the urgency and scale of the threat China poses. As a result, the unnerving truth is that the United States does not seem to be backing up its strong and, in many ways, commendable rhetoric with the degree of effort and focus needed to be ready to defeat a Chinese assault on Taiwan.

FROM REMOTE POSSIBILITY TO CONVENTIONAL WISDOM

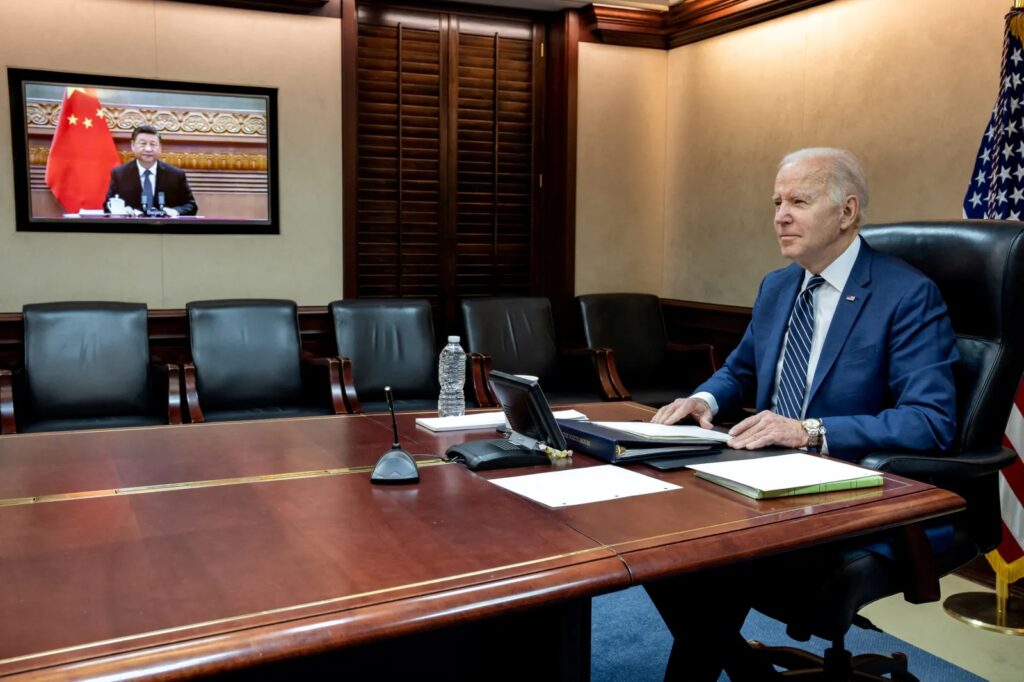

Until just a few years ago, many argued that China was not such a daunting threat to the United States and that its threat to Taiwan was modest or far over the horizon. Some voices still hold to those views. But the Biden administration has repeatedly made clear it does not.

Instead, the administration has assessed that China is the most significant challenge in the world to U.S. interests. Moreover, senior leaders are increasingly forceful and direct in their assertions that China’s military is a near-peer rival. As administration officials and senior military officers compellingly point out, the People’s Republic is in the midst of a historic military buildup, one that includes the dramatic expansion of its nuclear forces, rapid advances in critical military technologies that in key respects outpace U.S. innovation, and the construction of the world’s largest navy. Overall, official and expert assessments have made clear for several years now that the U.S. military advantage vis-a-vis China has eroded significantly and that China is continuing its daunting buildup.

The Biden administration has also been increasingly forthright about the growing threat of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. As recently as last year, many eyes rolled when Admiral Phil Davidson, then Commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM), warned that China might be able to successfully invade Taiwan by 2027. Davidson’s assessment now appears, however, to be the administration’s official position. As Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines testified in May, there is an “acute” threat of a Chinese attack on Taiwan. In using the specific term employed by administration officials to describe the threat from Russia after its invasion of Ukraine, Haines signaled a nearer-term threat from Beijing. Meanwhile, Bill Burns, director of the Central Intelligence Agency, stated that Xi Jinping had in no way dispensed with his goal of seizing Taiwan. More recently, in July, he stated that Beijing is determined to take over Taiwan and is prepared to use military action to do so; he also judged that Beijing would conclude from Russia’s experience in Ukraine that overwhelming force would be the right way to resolve the Taiwan issue in its favor. Department of Defense officials have also emphasized that a Chinese fait accompli against Taiwan is a real and pressing danger. At the same time, there are serious questions about whether the United States can actually win a war against China over Taiwan.

There are serious questions about whether the United States can actually win a war against China over Taiwan.

Against this worsening backdrop, the Biden administration has signaled that the United States will come to Taiwan’s defense, further strengthening perceptions that American credibility in Asia is linked to Taiwan’s fate. Most prominently, the President himself has indicated on no fewer than three separate occasions that the United States would defend the island. Moreover, despite staff-level disavowals of those comments, the fact is that his administration has telegraphed a strong commitment to Taiwan through a wide range of other avenues. For instance, the State Department has repeatedly described the U.S. commitment to Taiwan as “rock solid.”

These statements have not been confined to the political level. On the military side, the administration’s 2022 National Defense Strategy maintained its 2018 predecessor’s identification of China as the Department of Defense’s top priority. The Pentagon has formally designated Taiwan as the focus of a “pacing scenario” and underscored its commitment to being able to deny China’s ability to successfully pull off such an attack. Senior officials including Kathleen Hicks, deputy secretary of defense, and General Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, have meanwhile affirmed that a strategy of denial is the best way to deal with the threat China poses to Taiwan.

But here is the rub: the Biden administration’s actions to field a military that could actually deny a Chinese invasion of Taiwan do not appear to match its rhetoric. We can see the gap between words and actions by examining four critical levers the United States could pull: spending more on defense, transforming the American military to be better suited to taking on China, using the force in ways more focused on the threat posed by Beijing, and getting U.S. allies to contribute more, directly or indirectly.

SPENDING MORE

Setting aside the economic and political merits and demerits of such a course, spending much more on defense would give the U.S. military more resources to address the China threat. Bear in mind that China’s economy dwarfs those of the Soviet Union, Nazi Germany, or imperial Japan and that China has increased defense spending from year to year by six to ten percent for a quarter century. It has sustained these spending increases even in the face of slower national growth in recent years. Beijing’s defense outlays are now at least a third of the U.S. defense budget, with some respected analysts arguing that the real figure is much closer to parity. Moreover, China has the advantages of proximity, technological catchup, lower personnel costs, and focused attention on Taiwan and the Western Pacific, reducing the United States’ advantage of at least nominally higher defense spending.

Despite China’s growing military power, however, the Biden administration’s defense budget request for fiscal year 2023 was set below the rate of inflation. Its request for the previous fiscal year was also essentially flat. In effect, the administration proposed shrinking the defense budget. Although Congress beefed up the 2022 defense budget and seems likely to do so again for 2023, these actions still fall well short of the consistent year-on-year real growth of three to five percent deemed necessary by the 2018 National Defense Strategy, with its call for prioritizing China. Thus, that prioritization does not appear to be happening. In light of this, we can conclude that the administration has left the option of spending significantly more on defense to address the growing Chinese threat to Taiwan essentially unused.

OVERHAULING THE FORCE FOR CHINA

As for overhauling the military to focus much more on defeating a Chinese attack on Taiwan, the military is undertaking a range of promising initiatives. But it is far from clear that the Pentagon is investing adequately in developing and fielding the capabilities required to defeat an invasion, especially those needed in the coming decade.

Last year, for instance, Congress lambasted the Department of Defense for trying to use funds from the Pacific Deterrence Initiative (PDI), an effort specifically designed to meet INDOPACOM’s urgent requirements for improving the U.S. ability to defend Taiwan, to finance programs that were not even on the requirements list and would in fact be used across many regions. Although the department made better use of PDI this year, it still left INDOPACOM with $1.5 billion in unfunded requirements.

To make matters worse, the department continues to procure key munitions at insufficient levels for a conflict over Taiwan, even as the war in Ukraine has made clear that deep inventories of vital munitions are essential. For instance, the U.S. Navy recently informed Congress that the air force and navy had chosen not to produce critical long-range anti-ship missiles at the maximum rate that can be sustained by the U.S. defense industry despite lacking a near-term substitute. Similarly, the navy opted not to fully fund acquisition of SM-6 missiles or naval mines, both of which are critical for defeating Chinese naval forces in a Taiwan invasion scenario.

The Department of Defense continues to procure key munitions at insufficient levels.

The story with major defense platforms is just as troubling. In May, the chief of U.S. naval operations, Michael Gilday, testified that even the most optimistic option in the navy’s latest shipbuilding plan would be unable to meet the operational requirements for defeating a Chinese attack against Taiwan before the 2040s—15 years after the date when Davidson warned that Beijing aims to have the capability to take the island. Meanwhile, the navy is rapidly reducing strike capacity by divesting itself of cruisers, destroyers, and submarines that could contribute to a Taiwan fight (albeit at higher cost), despite not having any plausible capacity to replace them for years to come. Both the air force and the army have relegated key programs for such a fight—including critical spare parts, long-range fires, watercraft modernization, and assured precision, navigation, and timing systems—to their unfunded requirements lists, indicating they are a lower priority. This is a far cry from the major investments needed to restore what the war in Ukraine makes clear is necessary: a robust and active defense industrial base.

To be sure, there are important steps occurring within the Department of Defense to address the China threat. The Marine Corps’ Force Design 2030 is a clear example of such an effort. Crucial efforts are being made within the air force, INDOPACOM, the U.S. Strategic Command, the Office of the Secretary of Defense, and a few other places as well. But these appear to be less the norm than noble exceptions in their urgency and resolve to overhaul the military to meet the challenge. Most other signals, including those from the department’s most senior leaders, give the impression of something closer to business as usual than the “all hands on deck” approach that the situation merits.

Key U.S. officials and the nation’s most highly regarded defense experts warn that the changes required to deter China effectively are not occurring at the necessary scale and pace. Defense strategist Andrew Krepinevich, for instance, has repeatedly pointed out that the Joint Force has not yet developed and implemented an operational concept well suited to taking on China. In June, David Ochmanek, a former deputy assistant secretary of defense, wrote, “Neither today’s force nor the force that will exist in 2027… have all of the capabilities called for by the emerging joint operating concept” needed to defeat a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. Other highly informed and credible analyses point in a similar direction.

MORE ASIA, LESS ELSEWHERE

A third way for the United States to focus on China’s military threat to Taiwan would be to redirect and carefully husband U.S. military forces for that prospect. For instance, it was widely anticipated that the Department of Defense’s flagship Global Posture Review would announce significant new initiatives for the Indo-Pacific and shift the overall focus of U.S. military activity to that region. Yet the administration did not do so.

Indeed, in some critical ways, the United States has actually gone backward in its force posture. For example, the administration has increased U.S. forces in Europe from 60,000 in 2021 to more than 100,000 now. Moreover, according to General Christopher Cavoli, commander of the United States European Command, these levels are likely to remain at least until the cessation of hostilities in Ukraine. Given that the administration has judged that the war in Ukraine is likely to be protracted, this may well mean indefinitely.

Even worse, the administration has increasingly signaled that it intends to reengage in the Middle East. As if to leave little doubt about what this will mean for U.S. forces, General Michael Kurilla, commander of the U.S. Central Command, said, “This region is at the center of America’s strategic competition with Russia and China.” This is especially disturbing because a high demand for the diversion of forces to Central Command helped undermine the Department of Defense’s implementation of the 2018 National Defense Strategy during the Trump administration.

As a result, the overall deployment and positioning of U.S. forces is not enough to address the worsening military balance with respect to Taiwan.

GETTING ALLIES TO STEP UP

Inducing far greater military contributions from important allies, both in Asia concerning China itself, but also in other theaters such as Europe and the Middle East, would free up U.S. forces to focus on Asia. With the exception of some valuable efforts within Asia, however, the administration does not appear to be pressing allies to take on much more.

Instead, much of the administration’s rhetoric and engagement appear focused on reassuring allies that the United States will continue operating as it has in the past—as a dominant military presence across multiple theaters. For instance, Washington has not seriously pressed European allies to take on a greater role in the conventional defense of NATO or meaningfully sought to raise the level of expected defense spending, even though it should now be evident that the standard of two percent of each country’s GDP should be regarded more as a floor than an aspiration. By not insisting on greater allied assumption of responsibility in Europe and the Middle East, the administration’s message is far from what would seem to be needed to enable the Pentagon to concentrate more on Asia.

THE WRITING ON THE WALL

Stepping back, then, and surveying these four areas, we can see a fundamental mismatch between the administration’s stated goals and assessment of the threat and what it appears to be doing to address it. While commendable and important initiatives are taking place, there does not appear to be anything like the kind of fundamental change needed to produce a Joint Force ready and able to deny a Chinese assault on Taiwan in the shorter or longer term. It simply does not add up, especially when compared with the awe-inspiring and historic military buildup China is undertaking.

To be clear, the Biden administration is not alone in having allowed the United States to fall behind in preparing to meet China’s increasingly dire threat to Taiwan. To the contrary, the responsibility is generously shared across multiple administrations and Congresses dating back decades. Moreover, making a strategic shift is hard—both the Obama and Trump administrations struggled in their efforts to shift focus to Asia. Nor is it the Biden administration’s role alone to act: Congress, as well as the United States’ allies, must also do their part. But President Joe Biden and his team are the ones in charge now, when the situation is clear and urgent. It falls to them, therefore, to act to avoid disaster.

That said, we simply do not know whether China will attack Taiwan in this decade. But it is a reasonable presumption that Beijing is much more likely to strike if it concludes it would succeed, and significant factors indicate that it may judge this decade to be the most propitious one. The United States and its allies are now approaching or perhaps already facing a window of vulnerability over Taiwan. They cannot afford to only focus on the distant future and must confront both the near and longer-term threat. Even if it turns out that Beijing believes waiting until the 2030s is advisable, urgency is critical. Defense strategy is not a short-term matter; decisions taken now will often take years, if not decades, to bear fruit. Accordingly, the United States must act swiftly and sharply now, not only to confront the immediate threat but even to hope to be ready for the 2030s.

Beijing is much more likely to strike if it concludes it would succeed.

The administration seems to share this view of the threat and what needs to be done. Yet what it is doing does not seem to add up to a solution. If this assessment is accurate, this is a recipe for disaster.

We do not have access to all the facts. So let’s give administration officials the benefit of the doubt. How are they addressing this apparent mismatch in the coming decade and over the long term? Perhaps some of this cannot be publicly discussed, but surely the broad outlines can be. The voting public and its representatives must understand the nation’s overall plan and how it will be put into effect if they are to provide the support needed for an urgent shift to deter and thus avoid a war with China. During the Cold War, Washington provided very detailed and rigorous public explications of its strategies to deter and, if necessary, defeat Soviet aggression. Surely the current administration can at least approach the clarity and seriousness of such presentations.

Without such clarity or evidence of a sharp change, however, Americans must ask themselves: Is this how their government should be behaving if it actually thinks a major war with a peer superpower is looming? Surely not. And that should really worry us all.