One year after the Taliban seized power in Afghanistan, fighting has decreased considerably. Yet serious security problems remain, not least the foreign militants still in the country. External actors should press the new authorities to fulfil their commitments and avoid any steps that could reignite large-scale violence.

What’s new? The world’s deadliest war subsided into an uneasy calm after the Taliban took over Afghanistan in 2021. Violence levels are much lower, but ticking up, as the Taliban combat two insurgencies. Most worrying for outsiders is that the Taliban harbour foreign militants, such as the slain al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri.

Why does it matter? While none of these challenges seriously threatens Taliban rule for the foreseeable future, the de facto authorities are struggling to address them. In some places, they have eased heavy-handed tactics that alienated residents. Their handling of transnational jihadist groups has not inspired confidence – especially among neighbouring countries experiencing militant attacks.

What should be done? In seeking to protect their interests, foreign actors should avoid falling into past patterns of supporting proxies or routinely pounding their enemies from the air, neither of which is likely to improve security. Carefully circumscribed engagement with the Taliban may seem far-fetched but could be the best of bad options.

Executive Summary

The Taliban victory has brought a measure of unfamiliar calm to Afghanistan, as killing subsided in late 2021 across the vast majority of Afghan territory. But all is not well. The Taliban are fighting two insurgencies – one led by the Islamic State’s local branch and the second comprising the National Resistance Front (NRF) and other groups aligned with the former government. Of greatest concern to the outside world is that foreign militant groups that in the past relied on the Taliban for safe haven remain in the country, as shown by the 31 July U.S. strike that killed al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri in Kabul. Still, outsiders should resist any temptation to return to proxy wars or routine drone strikes. They should instead press the Taliban to honour their security commitments and, despite well-founded mistrust, offer modest collaboration on discrete issues. As for the Taliban, who bear primary responsibility for Afghanistan’s security, they must professionalise their forces, abandon collective punishment, and enforce their policy offering amnesty to officials and security forces of the government they overthrew.

The emerging picture of Afghanistan’s security landscape under Taliban rule reveals a country significantly more peaceful than a year ago, but with pockets of violence that threaten greater insecurity if not effectively managed. A key feature of the new landscape is the Taliban’s own changing force posture, which has visibly relaxed across much of the country. Hundreds of checkpoints on roads and highways have been dismantled, because the Taliban lack manpower to maintain them and, in any case, do not perceive major threats from the rural villages that hosted their fighters during the decades of insurgency. At the same time, they are still struggling to adapt to their new role policing the cities and parts of the north where they are unpopular. As they settle into Kabul and plan for the future, the Taliban have announced ambitious plans for a large security apparatus but efforts to build up these forces remain in early stages. The task is likely to take years.

Meanwhile, the Taliban face at least two small insurgencies. In the east and parts of the north, they battle the Islamic State-Khorasan Province (IS-KP). In the north, they also fight affiliates of the former army, police and intelligence services whom they defeated in August 2021. The brutal campaign against IS-KP has diminished its capacity in the east, but the group has begun to adjust, altering its area of operations and shifting its tactics – even making cross-border strikes in Afghanistan’s Central Asian neighbours, likely to signal the ability to act from the Taliban’s own backyard. At the same time, the largest of the northern insurgent factions, the NRF, has been gaining momentum despite – or perhaps in part because of – a Taliban crackdown.

As they confront these challenges, the Taliban have also (in a quieter way) been taking limited steps to manage the risks posed by other militants who remain largely dormant but dangerous. These include al-Qaeda and other jihadist groups with regional or global ambitions, which have historically enjoyed the Taliban’s protection. The Taliban’s way of handling of these groups aims at containing them without provoking them to turn against their nascent government. That precarious balancing act appears to have backfired and may no longer be sustainable in the wake of the U.S. drone strike that killed Zawahiri. His death made plain the contradictions in the Taliban’s desire to host global jihadists who in principle aim to bring down an international system from which the Taliban themselves seek recognition.

When security problems emerge, the Taliban’s first reactions have in some cases made them worse. They have tended to deny the existence of major issues, including by making absurd claims that al-Qaeda has no presence in the country. The Taliban issue similar denials about the scale of local insurgencies, presumably to thwart their adversaries’ publicity and recruitment efforts, while at the same time crushing dissent with heavy-handed tactics. These have included arbitrary detention, torture, extrajudicial killings, collective punishment and profiling whereby Taliban security forces target members of ethnic, tribal and religious groups whom they suspect of supporting insurgents or otherwise fostering anti-Taliban sentiments.

The Taliban themselves recognise that these harsh tactics have often generated backlash that drives Afghans to support the Taliban’s adversaries, and the authorities are therefore experimenting with more nuanced approaches to security. In some cases, they are relocating Taliban security personnel, to prevent their men from becoming enmeshed in local feuds, and offering to release prisoners on condition that tribal leaders offer guarantees of good behaviour. They have launched sweeping efforts at disarmament, including unprecedented house-to-house searches to hunt for weapons and confiscate materiel – dramatic steps, but less violent than other counter-insurgency tactics with which Afghans had become familiar over past decades. They are also enlisting the soft power of religious scholars, trying to persuade the entire country not to resist Taliban rule. Perhaps most importantly, the Taliban have reiterated a general amnesty, applicable to everyone who abstains from fighting them, and reached out to former enemies, urging their ex-foes to help rebuild state institutions – including the security forces.

” The question from the Taliban’s perspective is how to keep [the threats to the new regime] from worsening. “

While these initiatives are not yet curbing anti-Taliban violence, the threats to the new regime are not existential and the question from the Taliban’s perspective is how to keep them from worsening. Several future scenarios could pose graver risks to their control: pronounced fragmentation of the Taliban movement itself; opposition groups’ unification; or a revolt by jihadist militants against Taliban efforts to contain them. For now, those developments appear unlikely. Another danger could lie in regional and Western powers arming proxy fighting forces or Western countries resorting to a new routine of airstrikes or other unilateral action against foreign militants on Afghan soil, with unpredictable knock-on effects. The discovery of al-Qaeda’s leader in the heart of Kabul naturally will lead many foreign governments to doubt the Taliban’s ability or willingness to contain transnational militants. Indeed, the outside world understandably frets about the new Afghan authorities’ seemingly negligent approach toward jihadists who remain (at least for now) affiliated with the Taliban.

Still, outside powers’ first priority should be to avoid precipitating a return to high levels of violence in Afghanistan. The U.S. and its partners have made clear that they will retain an “over-the-horizon” capability to strike targets from bases in other countries. But the successful strike on al-Qaeda’s leader does not equate to a wider strategy: more bombing of militant groups will not eliminate them. Nor should foreign governments inflame violence in Afghanistan with a misguided return to proxy wars. Anti-Taliban rebel groups are highly unlikely any time soon to coalesce and prevail in a civil war, seizing Kabul, even with foreign funding. Instead, such tactics – upping the tempo of drone strikes or attempting to increase the capacity of the Taliban’s rivals to use force – are likely to result in civilian casualties, rising anti-Western sentiment and potentially even greater popular support for the Taliban. They would further fuel tensions between Western governments and the de facto authorities, blocking possible minimal cooperation on matters important to Afghans’ well-being and, perhaps, pushing the Taliban further into the arms of jihadists and encouraging defections to IS-KP.

A better way forward would be holding the Taliban to their commitments, including their promises to restrain transnational jihadist groups, offering in return limited help on practical security issues. The West will not entertain the idea of security cooperation with the Taliban, but opportunities remain for collaboration: for example, helping the Taliban curb arms trafficking and ensure safe storage of weapons stockpiles. If the outside world wishes the Taliban security forces would behave more professionally, donors might want to expand programs aimed at educating the Taliban about their legal obligations, including on civilian policing. Stronger border management would also require international cooperation, offering benefits for all sides. A major clean-up of landmines and unexploded ordnance could involve both the Taliban and outsiders. These steps do not require trusting the Taliban. On the contrary, it is precisely because the outside world is doubtful that the Taliban will provide security for Afghans and shield other countries from the spillover of Afghan insecurity that closer attention is warranted.

Still, it is the Taliban who now bear primary responsibility for the nation’s security, and the more they can do to shoulder that burden responsibly, the better it will be for all concerned – the Afghan people, outside actors and the Taliban themselves. As Afghanistan’s de facto authorities, they have a duty to develop security forces that protect rather than harm or alienate civilians. They should prosecute their own members who commit abuses, including breaches of the amnesty that is so important to conciliation with ex-enemies, in order to deter misbehaviour. They must stop targeting entire neighbourhoods, tribes and ethnic groups for the actions of individuals who take up arms against their government. Such steps would make Afghans less fearful that the country will plunge back into the abyss of war. They might also start a long, difficult journey toward practical cooperation between the Taliban and foreign governments on basic issues of peace and stability.

Kabul/Brussels, 12 August 2022

I. Introduction

The Taliban’s military takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021 put an end to 43 years of almost continuous war, an overlapping series of conflicts that reached a new ferocity as U.S. forces prepared for their departure. As the former insurgents took power, the world’s attention focused at first on the disastrous humanitarian and economic fallout.

Few outside observers took note of the dramatic shifts in the security situation, including a slowdown in the pace of violence to a level that most Afghans had not witnessed in their lifetimes.

Afghans certainly noticed the change. They had grown accustomed to a drumbeat of death and destruction: an estimated 20,000 to 40,000 battle fatalities per year, a toll that for several years had surpassed those of Syria, Yemen and Iraq, and more U.S. airstrikes than in any other part of the world.

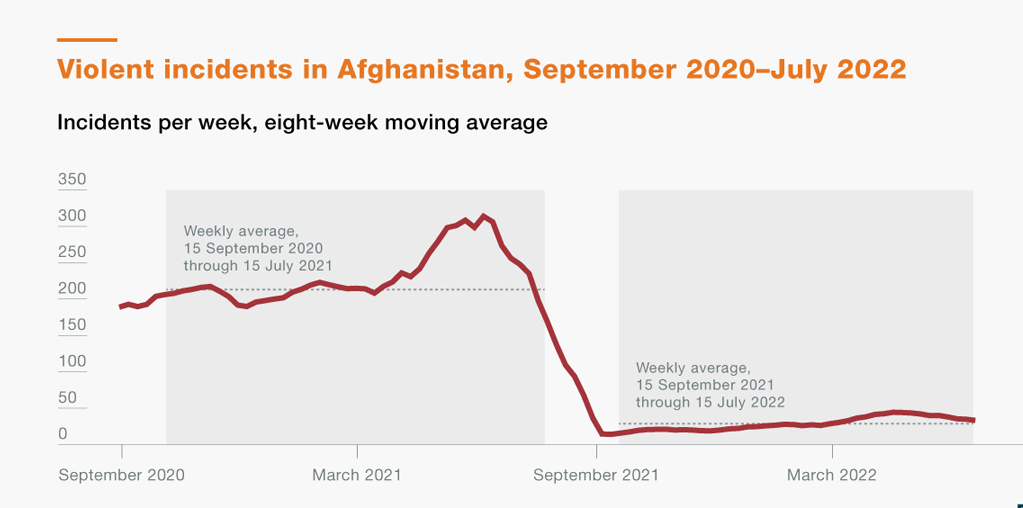

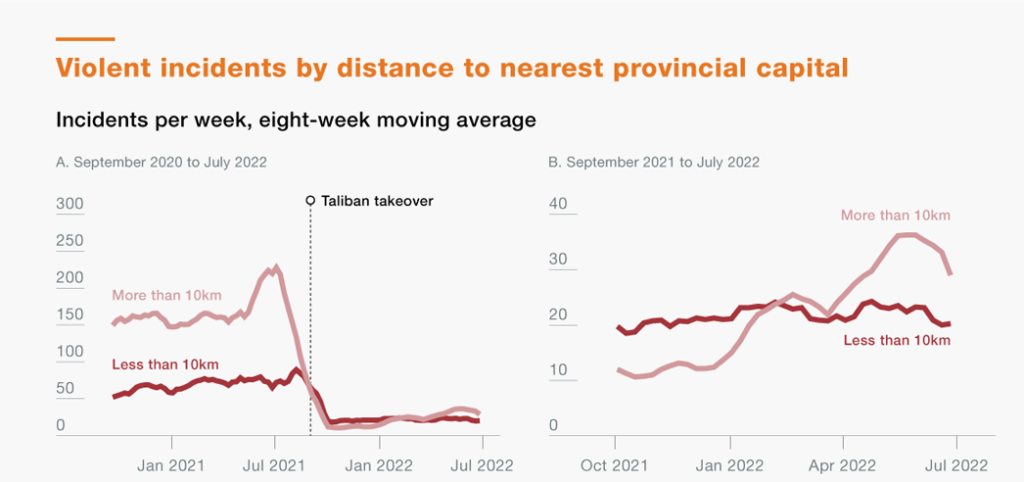

All of a sudden, after the Taliban seized power, the emergency wards were not full of Afghans suffering shrapnel cuts and blast injuries. In the early months of 2022, by UN estimates, fighting diminished to only 18 per cent of previous levels. Another comparison, of the first ten months of Taliban government against the same period a year earlier, found that the rate of battles, explosions and other forms of violence per week had fallen fivefold (as shown in Figure 1).

The war had forced hundreds of thousands of people to flee their homes in previous years, but during the early months of Taliban rule the informal camps and slums stopped swelling with fresh arrivals. By early 2022, only two of the country’s 34 provinces reported displacement as a result of conflict, and the numbers of displaced persons totalled less than 1 per cent of previous monthly peaks.

On the streets, however, nobody seemed certain that the relief from previous years of mayhem would last. Whether the lull in fighting was only a brief calm before another outbreak of civil war, or the start of a peaceful era, remained a frequent topic of speculation among Afghans watching nervously as the Taliban settled into power.

” Convinced that armed groups, regional powers and Western nations are undermining them, the Taliban have proceeded with a singular focus on consolidating control. “

Much now depends on what the de facto government will do – and, to a lesser extent, on the next moves from the emerging armed opposition and external actors.

Several groups have already declared armed resistance to Taliban rule. For the most part, the Taliban have responded to threats to their control with overwhelming brutality. Convinced that armed groups, regional powers and Western nations are undermining them, the Taliban have proceeded with a singular focus on consolidating control. Some of their harsh tactics are proving counterproductive, fuelling the very threats they seek to suppress, and in certain places the Taliban are re-evaluating their approach. At the same time, the Taliban’s continued toleration of jihadist groups raises concerns among foreign governments, which lack confidence in the Taliban’s ability to prevent new transnational attacks from Afghanistan.

This report canvasses the new security landscape in Afghanistan after the Taliban takeover, examining growing threats to the new government, the activities of armed groups such as al-Qaeda that have traditionally enjoyed the Taliban’s protection and the new authorities’ responses to both. Regional and international security concerns are considered, followed by options for engaging with the Taliban to mitigate them. This report does not cover the Taliban’s enforcement of restrictive social policies, or the implications of these policies for vulnerable groups such as women and minorities; these issues of personal insecurity will be addressed in forthcoming analyses of Taliban governance. The report is based on public and non-public databases of violent incidents, as well as dozens of interviews with Taliban officials, Western security experts, Islamic State affiliates, National Resistance Front supporters, regional actors and Afghans in thirteen provinces from November 2021 to June 2022.

II. The Security Environment

Obtaining an accurate picture of the security environment in Afghanistan has always been difficult, and it grew harder after the Taliban takeover. Publicly available datasets of violent incidents rely on media reports, which have become less reliable as the Taliban suppress efforts at enquiry and opposition groups exaggerate claims of small victories. In areas of intense fighting between rebel groups and Taliban forces, access for journalists and observers is limited. As a result, open-source datasets may not fully capture violence trends.

The information landscape is even more contested than the battlefield, as the public discourse about security is driven by starkly contrasting narratives. The Taliban often describe attacks on armed opposition groups as law-and-order actions against criminals and kidnappers. They sometimes block journalists in the country from investigating such cases, making it difficult to ascertain the identity and alleged crimes of targeted individuals.

On the other hand, armed opposition groups are increasingly claiming attacks on the Taliban government, but they sometimes try to document their hand in attacks with misleading videos; at other times, several different groups claim the same attack. Anti-Taliban groups also have incentives to fake or exaggerate incidents to garner media attention and raise funds abroad.

Despite the uncertainty, it is clear that two small conflicts are smouldering. One involves the local branch of the Islamic State, Islamic State-Khorasan Province (IS-KP), which emerged in 2015 and has intensified its attempts since then to challenge the Taliban. The second conflict involves actors formerly affiliated with the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, the political order that collapsed in 2021. The National Resistance Front (NRF) emerged as the biggest of these ex-Republic groups, primarily in Panjshir province north east of Kabul, but many others have proclaimed themselves. Conflict between the Taliban and predecessors of these groups dates back to the 1990s, but since the former’s ascent to power in August 2021, the roles of insurgent and counter-insurgent have flipped.

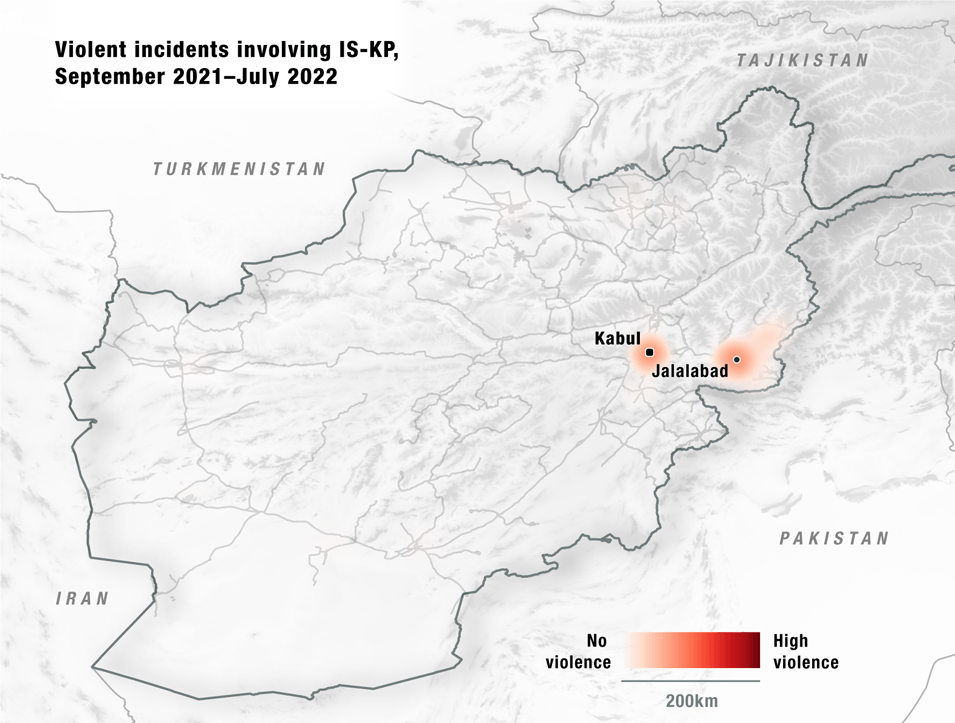

Thus far, neither of these two insurgencies seriously threatens the Taliban. The country has seen a sharp decline in violence, with insecurity concentrated in pockets of the east and north, in contrast with previous decades when almost the entire country was a war zone. When fighting breaks out, it is most often initiated not by insurgents but by the Taliban themselves, as the new authorities conduct offensive actions to consolidate power with armed force. Some of this skirmishing occurs as the Taliban remove unauthorised checkpoints and seize control of natural resources; other clashes involve opposition groups, criminals and renegade Taliban elements.

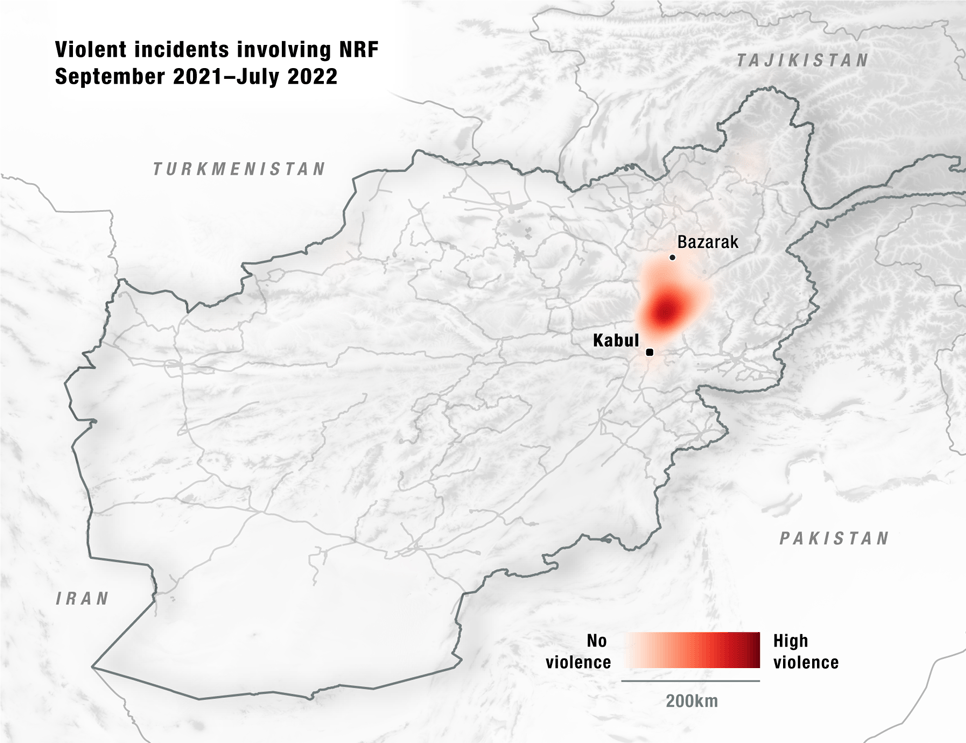

(Figure 2 shows the geographic concentration of violence.)

Figure 2. Geographic concentration of violent incidents in Afghanistan, 2020 – 2022.

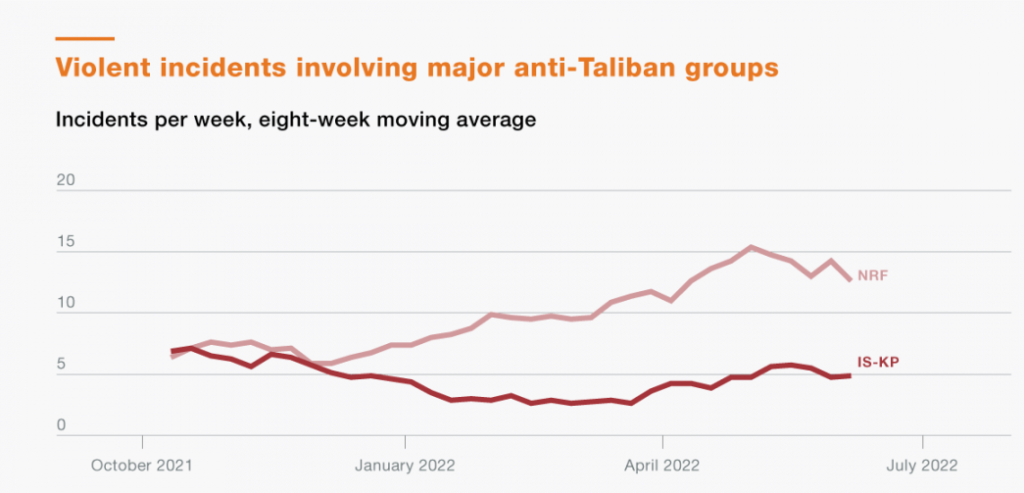

In cases where the Taliban do suffer attacks, large-impact bombings are usually claimed by opposition groups, while the majority of small-scale attacks remain mysterious and as discussed below may be attributable to a wide range of causes. When attacks on Taliban were claimed in the final months of 2021, it was usually by IS-KP. But after intense Taliban operations against the group, IS-KP attacks decreased in the first half of 2022. By contrast, anti-Taliban attacks in the north, where opposition groups are most active, have seen an uptick in the past few months, suggesting that these groups may be benefiting from the end of heavy snows in the mountains and gaining momentum. Most analysts agree that the pace of NRF attacks surpassed that of IS-KP strikes in the spring of 2022, trending upward into the summer. (See Figure 3, illustrating the number of attacks by both groups.

Identifying trends is complicated by the fact that it is often impossible to say who is killing whom. By some counts, more than half of attacks on Taliban personnel since October 2021 cannot be attributed. It is plausible that many unclaimed attacks relate to personal grudges or local feuds; in some instances, these involve ethnic, tribal or family dynamics emanating from political disputes, resource competition or historical grievances. Some attacks are perpetrated by individuals tied to the previous government, but not as part of any organised insurgency. These include tit-for-tat revenge killings by those whose families have been targeted by the Taliban, despite assurances of amnesty. Sporadic clashes have continued between the Taliban and irregulars previously associated with the Republic, such as the Afghan Local Police and pro-government militias. Other fighting appears to stem from conflict over resources, including land. Some violence results from criminality, which has increased as the economy has deteriorated.

Lastly, there is still intra-Taliban violence relating to quarrels over positions or other matters.

Whatever the cause of these unclaimed attacks, they appear to have slowly dwindled over the past ten months. In some provinces the drop-off reflects the Taliban’s consolidation of control, while in other places unaffiliated armed groups are joining organised resistance forces that advertise every anti-Taliban attack.

III. Armed Opposition to the Taliban

Two diverging trends dominate the security landscape. On one hand, the Taliban have stymied the expansion of IS-KP while, on the other hand, they are struggling to quell the growing northern insurgency. Outside but related to these trends, other groups connected with the previous government have also emerged to fight the Taliban, though they remain smaller than the ones in the north. Less active, but perhaps more dangerous, is the combustible mix of foreign militant groups such as al-Qaeda that remain loyal to the Taliban but could in the right conditions rebel against the new government.

A. Islamic State Khorasan Province

In the months following the Taliban takeover, IS-KP launched more attacks than ever.

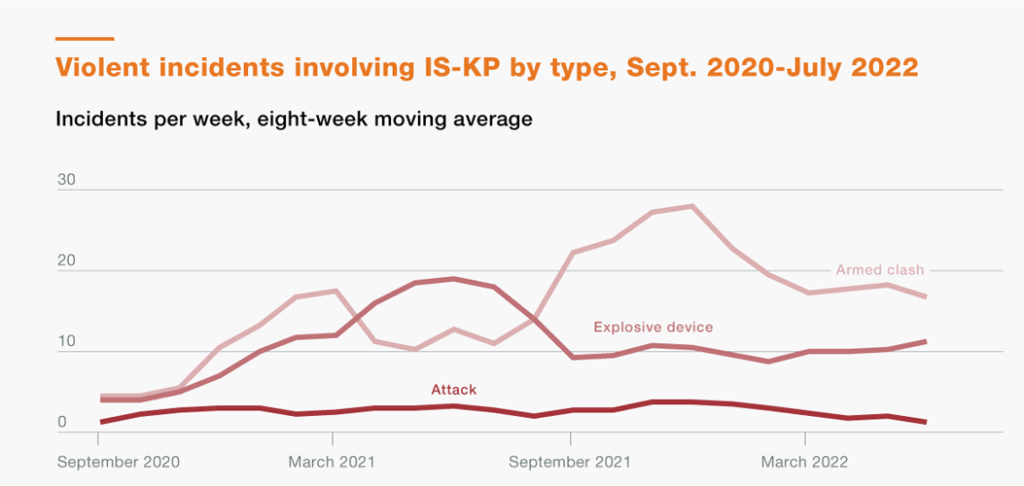

The spike in violence seemed to be driven by two factors: the chaotic aftermath of the Taliban victory over Afghan forces, which created a security vacuum in some eastern districts; and, more generally, IS-KP’s shift in tactics toward high-frequency, low-impact attacks. The tactical shift had started earlier, between 2019 and 2020, as IS-KP came under sustained military pressure and responded by decentralising and building clandestine networks with a focus on urban warfare. This adjustment followed losses of territory to the Taliban and strikes by Afghan and international forces in recent years. Deprived of rural strongholds, IS-KP reasserted itself in cities with a flurry of hit-and-run and sniper attacks targeting the Taliban after their victory. (See Figure 4, which shows the geographic scope of IS-KP activity.)

At first, the greater focus on urban areas worked well for IS-KP. The group was operating on familiar terrain, having historically recruited from the educated classes, and especially Salafists, in cities such as Kabul and Nangarhar. The fact that the Taliban had limited experience with urban counter-insurgency was an advantage for IS-KP. The mass escape of hundreds of IS-KP prisoners during the Taliban’s sweep to power also provided impetus and energy to the insurgency. Escapees reactivated their networks and conducted a barrage of attacks on Taliban personnel.

The Taliban started to regain the upper hand in late 2021, launching a vicious counter-campaign against IS-KP in cities, and forcing IS-KP (whose attacks diminished significantly) to change its tactics yet again. The group lost some of its operational capacity in the eastern province of Nangarhar but continued attacking Taliban forces next door in Kunar province, including with occasional ambushes of isolated checkpoints using heavy weaponry. Beyond its historical stronghold in the east, the group expanded its geographic scope with sporadic attacks in the south and west and more frequent attacks in the north. Rather than confronting the Taliban militarily, IS-KP primarily directed its attacks at the country’s Shia Hazara and Sufi minorities, which the group has routinely targeted from its outset.

Most of these operations were scattered incidents, suggesting a limited IS-KP presence in those regions, but attacks in the north appeared to be more concerted – hinting that the group might be developing a foothold outside of its eastern redoubts.

This diffuse approach and other tactical adjustments helped IS-KP to avoid exposing its members to reprisals by Taliban security forces in early 2022. In addition to focusing on soft targets among defenceless Shia and Sufis, it ramped up a campaign against Afghanistan’s neighbouring countries that was mostly symbolic. IS-KP claimed rocket attacks upon both Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, but these strikes do not appear to have been intended to inflict military losses. Rather, their effect was to undermine the Taliban’s narrative that only a Taliban-led government could bring peace and stability to the country, in part because it could stop militant groups from carrying out cross-border operations.

These adjustments to the fast-changing environment showed IS-KP’s nimbleness and resilience. (See Figure 5, which illustrates IS-KP tactical shifts.)

Because of the intractability of the feud between IS-KP and the Taliban, the former will probably continue to adapt in response to military pressure, looking for new ways to undermine its existential foe. The feud is rooted in wider debates between Salafism and Deobandism, two movements within Islam. IS-KP accuses the Taliban of being apostates and polytheists, while the Taliban considers IS-KP Salafists to be khawarij or heretical extremists. One aspect of the ideological dispute is a difference of opinion about the world order: the Islamic State seeks to disrupt it, while the Taliban have positioned themselves as a player within the system of nations. Against this backdrop, IS-KP’s attempts to lure fighters away from the Taliban appear to have met with little success so far, but the group will keep trying. IS-KP continues to enjoy financial and political backing from its parent organisation, and its members retain some capacity to operate across borders in the region.

B. National Resistance Front

Armed groups composed mostly of people affiliated with the previous Republic surpassed IS-KP as the most active opposition to the Taliban in early 2022. These included many of the same figures who had fought the Taliban in the 1990s: former monarchists, members of the old pro-communist regime and assorted mujahideen.

Most of these groups had been on the losing side of their conflict with the Taliban until the international intervention in 2001. Their ranks now include a younger generation that defined itself in opposition to the Taliban insurgency over the last two decades.

The largest of these resistance groups is the National Resistance Front (NRF), reportedly led from Tajikistan by Ahmad Massoud, the son of famous mujahideen commander Ahmad Shah Massoud, whom al-Qaeda operatives assassinated on 10 September 2001.

The NRF is primarily active in Panjshir province and adjacent areas in the north, including in parts of Baghlan, Parwan and Kapisa provinces. It also retains some capacity in Kabul. The group’s opposition to the Taliban began immediately after the insurgents took over on 15 August 2021, when Panjshir was left the only province outside the Taliban’s control. A few days later, an uprising in Baghlan’s Andarab region repulsed Taliban forces.

The Taliban quickly sent forces to Andarab and Panjshir and established control over major settlements, but outlying areas remained rife with insurgency.

Since then, the number of NRF attacks has been relatively modest but growing: by the early summer of 2022, there were a dozen or more attacks per week.

In Andarab, NRF fighters have gained limited capacity to confront Taliban security personnel, but they usually withdraw to mountain redoubts, avoiding direct clashes, when the Taliban send reinforcements. In Panjshir, NRF fighters have maintained covert positions in the mountains but have so far failed to hold a single district. NRF activities in Panjshir, Parwan and Kapisa provinces primarily consist of hit-and-run attacks, occasional ambushes on remote Taliban checkpoints and patrols, and, rarely, assassinations of Taliban officials, including with improvised explosive devices. (Figure 6 shows the areas of NRF activity.)

Most armed opposition groups in Panjshir and surrounding areas nominally operate under NRF command, albeit with little hierarchy or strategic coordination. The group’s leadership is mostly outside Afghanistan, and local commanders often work independently with little direction from abroad. This flexible structure – similar to how the Taliban operated as an insurgency – allows the NRF to absorb smaller groups that start fighting the Taliban as a result of local grievances.

” [The National Resistance Front]’s rhetoric is calibrated to attract regional and international support against the Taliban government. “

The NRF’s messaging focuses on the protection of rights for ethnic minorities, with some senior members advocating devolution of power to provinces to allow greater independence from Kabul. The group does not promote a return specifically to the previous system of government, and its supporters sometimes disparage former government leaders for, in their view, allowing the Taliban to achieve victory. Speaking to foreign audiences, the group invokes ideas of freedom and self-determination, along with stoking fears of international terrorism. This rhetoric, often reflecting genuinely held views, is calibrated to attract regional and international support against the Taliban government. Senior NRF figures tell interlocutors abroad that their goal is to pressure the Taliban into negotiations, although perhaps not in the short term.

Speaking to Afghan audiences, the message is somewhat different. NRF supporters on social media focus on grievances of the Tajiks, an ethnic group that is most populous in the north, and the near-monopolisation of power by Pashtuns, the largest ethnic group and the main Taliban constituency.

These narratives have been a major part of political discourse for decades. Under previous governments, non-Pashtun groups complained that the Pashtun-controlled presidency wielded too much power and, allegedly, had too much affinity for fellow Pashtuns among the Taliban.

Such messages, playing on Afghanistan’s ethnicised politics, appear to be limiting the NRF’s expansion beyond its northern strongholds, for now.

Still, the group has broadened its appeal by enlisting the support of the former army chief of staff, General Qadam Shah Shahim, and by portraying itself as a haven for other former security personnel who face Taliban abuses. It also appears to be seeking to attract breakaway Taliban factions, such as that led by Mawlawi Mehdi, an ethnic Hazara commander who rebelled against his Taliban comrades.

Whether this strategy will bear fruit in bolstering the NRF’s ranks remains to be seen.

C. High Council of National Resistance

A more recently formed anti-Taliban group, the High Council of National Resistance for Saving Afghanistan, includes many factional leaders who gained prominence in the 1980s and served as part of the post-2001 government.

The group announced itself in May, condemning Taliban abuses and autocratic governance, while calling for a peaceful resolution of disputes. The group has not claimed any military activities, but fighters affiliated with Council member Atta Mohammad Noor, a northern politician, have declared their intent to wage armed resistance in the Andarab region as well as Sar-e Pol, Samangan and Bamyan provinces.

The Council shares historical affinities with the NRF, including overlapping membership in Jamiat-e Islami, a faction that gained prominence in the 1980s and enjoyed a share of power after 2001. Supporters claimed that the Council would join forces with the NRF, but the merger does not appear to have occurred. In any case, NRF affiliation with the Council might be politically fraught, because its members have lost prestige after fleeing the Taliban amid allegations about the corruption of recent governments.

D. Other Insurgent Groups

Other groups connected with the previous government have also emerged. Like the NRF, many have a history of opposition to the Taliban that predates the Republic. Others represent a younger cohort, mostly former Afghan security forces personnel who battled the Taliban in recent decades. Some of these groups have not shown much operational capacity beyond social media announcements, or they exaggerate their limited presence on the ground.

At times, two or more groups claim credit for a single attack. These disparate groups have so far failed to coalesce into a single insurgency fighting the Taliban, and where they operate on shared terrain they sometimes compete for resources.

Arguably the most prominent of these smaller groups is the Afghanistan Freedom Front, led by the former chief of the general staff, General Mohammad Yasin Zia. Although less active than IS-KP or the NRF, this Front has claimed dozens of attacks since early 2022. Its activities are primarily in the north, but also geographically dispersed. The group has tried to lure fighters away from the NRF, including in the Andarab region, and it may succeed in places where the NRF’s appeal is limited by its affiliation with Jamiat-e Islami and ethnic Tajiks.

By contrast, Zia’s group is not linked to any historical or ethnic faction, a fact that raises its chances of winning broader popular support in the medium term.

The Afghanistan Islamic National and Liberation Movement, which announced itself in February, also purportedly consists of personnel from the former security forces. The group has claimed nearly two dozen attacks in the south and east.

It appears to consist largely of Pashtuns and concentrates on the Taliban’s southern heartlands.

Other insurgent groups are still nascent, with limited presence on the battlefield. These include the Liberation Front of Afghanistan, Freedom Corps Front, the Unknown Soldiers of Hazaristan, the Freedom and Democracy Front in Hazaristan, the Western Nuristan Front and the South Turkestan Front.

E. Foreign Militant Groups

Conflict between the aforementioned groups and the Taliban accounts for much of the violence in Afghanistan since August 2021, but a number of foreign militant organisations could also pose internal and external security threats, despite having claimed no attacks since the Taliban takeover. Al-Qaeda leader Ayman Zawahiri’s presence in Kabul was symptomatic of a broader problem: in addition to al-Qaeda and its local chapter, al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent, other foreign groups have a limited presence in Afghanistan. These include Jamaat Ansarullah, Jaish-e-Mohammad, Lashkar-e-Tayyaba and bands of Uighur fighters.

There are also remnants of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan that remain loyal to the Taliban. Most of these groups appear to share some ideological affinity with the Taliban and to be under their supervision. The largest externally focused militant group is Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), which appears to have thousands of fighters and supporters in Afghanistan, although it is mostly composed of local insurgents in Pakistan.

” [Foreign militant] groups remain allied with the Taliban, and appear to be steering clear of any organised resistance to their rule. “

For now, these groups remain allied with the Taliban, and appear to be steering clear of any organised resistance to their rule. Yet their mere presence poses security risks for the Taliban, even beyond the possibility of operations by other governments against them. Were any foreign militant group to defect to the anti-Taliban side, that could not only reinforce resistance in itself but also erode the Taliban’s own cohesion. The Taliban government continues to routinely deny the presence of these fighters, even when their activities seem undeniable.

The most brazen example has been the Taliban’s reaction in the days after Zawahiri’s death, when a spokesman initially claimed, absurdly, that the U.S. drone strike hit an empty property. In private, the Taliban claim to be taking steps to curtail such groups’ independence and to prevent them from joining the armed resistance, as discussed further below.

IV. The Taliban’s Response

With new responsibility to secure the country and the challenge of operating on new terrain, the Taliban have adjusted their force posture and employed a mix of tactics – often relying on brutal methods to assert control, but in some cases pivoting to approaches that, compared to what others have done in Afghanistan, are more nuanced.

A. Reoriented Force Posture

In the months following their takeover, the Taliban started to dismantle the vast system of checkpoints maintained by both sides in the 2001-2021 conflict.

Interlocutors who travelled on roads throughout the country said checks had diminished significantly, making it easier to get around. Taliban security officials said they had relaxed precautions in most of the country because it had become safer, instructing their forces to keep questioning of civilians to a minimum. Scrutiny at checkpoints focused on persons carrying weapons, including Taliban members.

” Personnel shortages after August 2021 forced the Taliban to concentrate their units in key areas. “

Part of the Taliban’s motivation for removing checkpoints may have arisen from a lack of manpower. The Taliban never required a large standing army during their insurgency, when most of them fought within walking distance of their own homes. Estimates of their forces’ numbers were often exaggerated, but it is clear that the Taliban suffered heavy casualties in the war’s final stages.

The resulting personnel shortages after August 2021 forced the Taliban to concentrate their units in key areas – on the borders, at the entry points to provincial capitals and along parts of major highways – especially in provinces perceived as prone to rebellion.

Securing this terrain allowed the Taliban to curtail the armed opposition’s movements.

In early 2022, Taliban officials began signalling that additional changes were afoot with respect to both force numbers and posture. In a series of announcements, the government revealed that it would build formal security forces numbering in the hundreds of thousands, maybe surpassing the size of the Republic’s security apparatus.

At the same time, the Taliban dispatched additional units to the borders with Pakistan and Tajikistan, in response to the growing TTP, IS-KP and NRF activity. Another reason for heightened security along the borders could be to curb smuggling of weapons out of Afghanistan from the huge caches left behind by Republic forces. The Taliban also dedicated significant numbers of fighters to Nangarhar, as well as Panjshir and surrounding provinces, to suppress IS-KP and NRF threats.

B. Navigating New Terrain

The Taliban have struggled to adjust to their role as security providers, especially in cities and the northern mountains where they have little experience. As a rural-based insurgency, the Taliban had been successful in securing parts of the countryside with tactics geared toward preventing rivals from gaining a territorial foothold. They manned some checkpoints but generally operated as a mobile force that patrolled remote areas, especially at night. The Taliban continued these habits in government. As one Western observer put it, “The Taliban are not ready to give up their ownership of the night”.

Yet lurking in the darkness of distant places was not a good way to secure urban centres, which experienced crime waves in the initial aftermath of the previous government’s collapse. The Taliban found that they were vulnerable as well; after they seized power, they suffered lethal ambushes in rural areas and even more so in crowded cities such as Jalalabad and Kabul.

As discussed earlier, IS-KP has sought to exploit the Taliban’s weakness in urban areas by shifting its operations there.

In the final months of 2021, IS-KP launched near-daily attacks upon the Taliban in Jalalabad, for instance, and the Taliban responded by sending several units of fighters to the city. Taliban forces reoccupied most of the installations previously manned by the former government, constructed new checkpoints and set up mobile roadblocks. Residents said the Taliban focused on checking rickshaws, a common vehicle for IS-KP fighters.

These tactics curbed, but did not stop, the violence.

The Taliban had less success with dislodging guerrilla fighters perched in the Hindu Kush mountain ranges in the north. Although the Taliban have experience with mountain warfare, they lack familiarity with parts of Baghlan and Panjshir provinces where they had virtually no fighters in past decades. In these areas, fighters primarily affiliated with the NRF launched repeated harassing attacks around settlements in the valleys before withdrawing into the mountains.

In the summer of 2022, the Taliban sent reinforcements into the Hindu Kush, turning narrow valleys into heavily militarised zones and establishing checkpoints that restricted the flow of traffic. In places where the Taliban pushed rebels from their mountain bases, they set up checkpoints manned by fighters from other provinces – but such deployments were the exception in the overall strategy, as described below.

C. Counter-insurgency Measures

In the pockets of terrain where the Taliban have faced renewed insurgency, they have employed diverse tactics for dealing with armed opposition. These range from denial and downplaying of threats, to heavy-handed human rights violations, to a range of less violent methods aimed at mitigating anti-Taliban resistance.

Denying and downplaying threats.. The Taliban’s instinct upon taking power was to say they had no security problems. The new government initially dismissed IS-KP as “mere propaganda”.

Its comments about the NRF were sardonic, portraying the rebels as keyboard warriors taking orders from discredited politicians living overseas. In early May, as the NRF launched attacks on Taliban forces, the government said nothing had happened. This strategy seemed aimed at denying opponents publicity and recruitment opportunities. When speaking about IS-KP or the NRF, the Taliban usually portray them as nuisances rather than serious challenges – although they may speak differently of IS-KP depending on the audience. To diplomats, the Taliban present themselves as a bulwark against IS-KP expansion. To Afghans, they depict IS-KP as a small group supported by foreign intelligence agencies. To fellow Islamists, they label IS-KP as rejectionists of legitimate Islamic rule – using terms like khawarij, takfiris or bughat – and generally refer to the NRF as bughat as well. These labels imply a religious justification for targeting the groups.

Heavy-handed measures. While they speak dismissively of armed resistance groups, the Taliban have pursued them with deadly seriousness. Some of their heavy-handed tactics are reminiscent of those practiced by the former security forces and their international allies during the decades-long campaign to eliminate the Taliban. These allegedly include night raids, arbitrary arrests, torture, forced confessions, mass reprisals, extrajudicial killings and the mutilation of enemy corpses.

Other forms of abuse have become more prevalent under the new government, including the profiling and targeting of anti-Taliban communities, especially with evictions and large-scale house-to-house search operations. The Taliban’s attempts to suppress actual or suspected armed opponents have been the most common cause of violent incidents throughout the country since they took power.

Arbitrary detention. The Taliban have captured and held significant numbers of people suspected of belonging to resistance groups without the benefit of judicial safeguards. The total count is unknown, but officials claimed that “hundreds” of NRF fighters surrendered in early May alone.

So far, the Taliban have not announced that any of these detainees have appeared in court. Nor is there any indication that detainees are provided with legal representation or accorded any form of due process. Local sources report accusations that security and intelligence officials are often picking up civilians on suspicion of links to armed groups or even relatives of opposition figures as a form of punishment. Detainees’ fates often seem to be determined by political considerations, with some being held incommunicado and others being pardoned, sometimes after local elders provide guarantees of their good conduct.

Extrajudicial killings and torture. During the Taliban campaign against IS-KP in Nangarhar, unconfirmed social media footage emerged of suspected IS-KP members’ mutilated corpses left lying in public, presumably to deter other group members. UN human rights officials have stated that the Taliban extrajudicially killed at least 50 suspected IS-KP members, including by hanging and beheading – and then displaying the corpses.

Others have claimed higher numbers of extrajudicial killings. More recently, human rights organisations have accused government forces of torture and summary executions of suspected NRF members in Panjshir province.

Evictions and reprisals. The Taliban have a history, extending long before their takeover of the government, of evicting families of suspected IS-KP members and burning down their houses.

As the new government, the Taliban has continued this practice, holding families and extended relatives responsible for released prisoners, and sometimes kicking them out of their homes as punishment in cases of recidivism. Some evidence suggests that the government might also be using the same tactics, on at least a limited scale, against suspected NRF fighters in northern Afghanistan. Taliban officials denied accusations of evictions, arguing that the families in question were displaced by fighting.

Profiling and collective punishment. Especially during their first months in power, as they struggled to fend off IS-KP and the NRF, the Taliban targeted communities perceived as supporting these actors. Because IS-KP members are mostly Salafis, the Taliban imposed blanket restrictions on that religious minority, inflaming tensions with its members.

Following IS-KP attacks in late 2021, the Taliban partially closed down Salafi madrasas in the IS-KP strongholds of Nangarhar, Nuristan and Kunar provinces, and some farther away in Kunduz, Takhar and Balkh provinces. Some Salafi scholars and seminary teachers turned up dead with notes pinned to their bodies accusing them of being IS-KP supporters. At other times, the Taliban executed political opposition figures for alleged ties with IS-KP.

(As discussed below, such killings slowed in 2022 as the Taliban adopted more varied ways of dealing with IS-KP.)

The Taliban also started using profiling tactics against ethnic Tajiks after the NRF’s resurgence in early 2022, suggesting a correlation between levels of armed group violence and restrictions on communities perceived to be sympathetic to those groups.

Protesters and critics who expressed support for the NRF, or were viewed as sympathetic to the group, were detained. Residents of Panjshir province, especially those with historical ties to the former Northern Alliance or the former Republic security forces, faced particular scrutiny.

During the Taliban’s house-to-house search operations in Kabul and adjacent areas, accusations emerged suggesting at least some Tajik family homes were searched more thoroughly and, in some cases, ransacked due to suspicions of support for the NRF or criminality. One explanation is that the new authorities have sought to compensate for their lack of well-organised policing and accurate intelligence by relying on profiling and collective punishment.

Tactical adjustments. The Taliban’s rough tactics have not entirely succeeded and may in certain cases have proven counterproductive – prompting a change in approach, at least in some locations.

For example, senior Taliban security officials from Nangarhar province conceded that their repressive measures were creating grievances that were bolstering rather than hindering IS-KP recruitment.

In that province and others, the Taliban changed tactics several times in an effort to dispel perceptions that they are governing with brutal methods and to more effectively drain support for IS-KP and the NRF. Starting in late 2021, they placed new emphasis on structural and personnel changes in the security apparatus to improve command and control, offered clemency for captured opposition fighters, made attempts at widespread disarmament and launched efforts at winning local support for the government. These tactics were not entirely new to the Taliban, but they seemed to be relying more frequently on such measures.

Reshuffling of security personnel. Because the Taliban exploited local grievances to expand recruitment when they were insurgents, they are keenly aware that popular discontent can fuel opposition.

When faced with rising insecurity or intra-Taliban tensions, the new government has been quick to replace local officials with outsiders who have no stake in local ethnic, tribal or other dynamics and are therefore less likely to exacerbate existing rifts. For example, when IS-KP launched an offensive in September 2021, the Taliban immediately replaced the governors of Kunar and Nangarhar with senior officials from other provinces. A similar reshuffle followed a spate of violence in the north in May, with the Taliban appointing new security officials in several provinces. In both the north and east, the new appointees were reinforced by fighters from other provinces with little stake in local dynamics.

This approach had benefits – cementing Taliban command-and-control, while distancing their officials from local politics – but it also had downsides. Eager to stamp out resistance, some of the freshly dispatched officials treated locals with suspicion. Complaints emerged of security operations that failed to respect local customs. Some of these problems were remarkably similar to those faced by the previous government.

Pardons and conditional releases. The government also has tried offering pardons and conditional releases to some captured enemies, mostly IS-KP. The Taliban used similar tactics when they were insurgents; they often released detainees with guarantees from village elders that the alleged culprits would not repeat their offences. At first, the Taliban tended to release IS-KP detainees unconditionally and pardon new captures. It also acted with leniency toward the IS-KP prisoners who escaped in a series of prison breaks as the Taliban took over in the summer of 2021, allowing those who returned home to be included in the new authorities’ general amnesty.

This approach raised concerns, however, among Taliban officials who suspected that IS-KP was using the opportunity to reactivate its networks; as a result, local authorities started to revive the practice of demanding guarantees from tribal elders.

In some cases tribal elders also promised to punish future culprits, including by banishing them and burning down their houses.

Such methods were still crude, but less violent than some of the Taliban’s other counter-insurgency tactics.

House searches and weapons seizures. The Taliban have also taken sweeping preventative measures in an effort to control the vast supplies of weapons, ammunition and other materiel in the country. In December 2021, the government announced that the High Commission for Security and Clearance Affairs, led by Deputy Defence Minister Fazil Mazloom and including police, intelligence and defence officials, would be responsible for collecting and disposing of ordnance.

That commission then took a leading role in house-to-house searches in many parts of the country, including Kabul, where in February 2022 it took the unprecedented step of ordering every home in the capital searched. While authorities justified the search as a crime-fighting measure, a key purpose was to collect firearms. The commission quickly extended these operations to Panjshir, Parwan and Kapisa provinces, all NRF bastions. Similar campaigns later took place in Logar, Laghman, Baghlan, Takhar, Herat, Badghis and Nangarhar provinces. Taliban officials told Crisis Group that the de facto authorities plan such operations across the entire country.

In addition to reducing the number of privately held weapons and armaments, the searches sought to pre-empt opposition plans for a spring offensive by diminishing its firepower. Driven by similar objectives, the commission is expected to continue such operations in other parts of the country. The Taliban seem especially concerned about weapon caches reportedly held by NRF fighters in Panjshir province and those belonging to an ethnic Hazara commander, Abdul Ghani Alipoor, in Wardak province. Security forces, particularly the Taliban intelligence agency, across the country have been taking steps to confiscate stockpiles.

Enforcing the amnesty, and outreach to former enemies. The Taliban publicised a general amnesty as their forces began capturing large swathes of territory in the summer of 2021, but it has been unevenly enforced. This amnesty promised all former government officials, including security forces, and others associated with the previous political dispensation the right to live peacefully and without harassment under Taliban rule.

That pledge weakened the Republic government’s final stand against the insurgency by allaying fears that might have led the old guard to hold out. Taliban forces mostly respected the amnesty during the takeover, but after seizing power they were accused of widespread breaches. Reports of the total number of reprisal killings varied, sometimes ranging into the hundreds. The sporadic nature of reprisals, and their low numbers relative to the size of the Republic’s political and security apparatus, suggested that it was not the Taliban’s nationwide policy to hunt down all former government officials. Still, the Taliban detained and interrogated many former security officials in areas, such as Nangarhar and Panjshir, where armed opposition was fiercest.

” Cognisant that reprisals helped armed opposition groups draw recruits, the Taliban have increasingly preached the importance of respecting the amnesty order to their members. “

Cognisant that reprisals helped armed opposition groups draw recruits, the Taliban have increasingly preached the importance of respecting the amnesty order to their members, even framing it as an Islamic obligation.

While Crisis Group is not aware of any record of a Taliban fighter being tried before judicial authorities for gross violations of the amnesty, some have allegedly been imprisoned on those grounds. Between September 2021 and February 2022, the Taliban claim to have disarmed and removed 4,350 “undesirable” individuals from their ranks, including for amnesty breaches.

The Taliban also established a “high commission” for outreach to prominent Afghan exiles, welcoming them back to the country in a bid to prevent them from joining opposition camps.

In the first half of 2022, this commission offered safe return to dozens of Afghan political figures, including former senior defence officials. High-profile returnees have been promised a warm reception, as well as Taliban security escorts and other welcoming gestures. In addition, the new government has increasingly recruited into its ranks former security personnel, particularly those with technical and administrative skills. Former security officials have been appointed to key, though not top-level, positions.

Seeking religious support. The government has also used Islamic scholars to bolster itself and undermine insurgents. In Nangarhar, Kunar and Badakhshan provinces, local authorities publicised pledges of allegiance by gatherings of Salafi scholars, who condemned violence by IS-KP as “non-Islamic”.

In Panjshir, the government appointed a provincial ulema council (ie, a body of local clerics) tasked with mediation and public outreach. Council representatives appeared to have political backing from central Taliban authorities, as they gave advice to provincial officials, monitored allegations of mistreatment by Taliban fighters and mediated local grievances. The Taliban have invested heavily in such efforts to legitimise their rule, most prominently by bringing 4,500 clerics from across the country to a grand assembly in July, culminating in a declaration of support for Taliban leadership.

D. Few Successes, But Growing Challenges

The Taliban’s strategy for suppressing armed opposition has produced mixed results, with some measures proving effective and others markedly counterproductive. In Nangarhar, the elevated security presence resulted in a clear reduction in armed opposition activity.

Similarly, the government’s sweeping house-to-house searches correlated with a drop in opposition attacks in targeted areas, for a short time. But such intrusive operations (even if less brutal than some other tactics the group employs) could be inflaming local sensibilities and fuelling recruitment for armed opposition groups. The Taliban’s most heavy-handed measures – such as arbitrary detentions, torture and extrajudicial killings – continue to deepen grievances. The Taliban’s use of profiling and collective punishment also risk driving entire communities into the hands of their opponents.

Overall, despite some efforts by the Taliban to pivot away from their harshest tactics and develop more nuanced approaches to curbing the northern and eastern insurgencies, they did not stop the erosion of security in early 2022. Violence declined precipitously after the Taliban takeover but has started to rise again. Although skirmishes are increasingly fought away from population centres (as shown in Figure 7), violent incidents have lately begun to tick up moderately.

V. Four Scenarios for Destabilisation

In the near term, the Taliban do not face a threat to their grip on power from the disparate armed groups arrayed against them. Still, the challenges to Afghanistan’s latest government are far from resolved and could have implications beyond its borders. The following scenarios – unlikely for now but possible over the medium term – are among the most threatening from the perspective of destabilisation.

A. Fragmentation of the Taliban

One scenario that could dramatically increase insecurity would be the Taliban movement’s fragmentation. Some senior government figures could have incentives to break away from the Taliban if they come to feel that they have not sufficiently benefited from military victory.

Largely for this reason, the new authorities stacked the government with Taliban stalwarts, refusing to share power with those outside the movement, and instead seeking to make sure that all parts of the former insurgency were rewarded.

There are few, if any, major Taliban figures who are not serving in the new government, albeit in roles with widely varying influence. Although individual Taliban members have reportedly joined armed groups, including IS-KP, no major commander appears to have defected for now. High-profile resignations would be a sign of fissures, but to date they have not occurred.

Still, intra-Taliban disagreements persist. The harsh repression of Salafis and other minorities in rebellious areas could alienate members of under-represented religious and ethnic minority groups within the movement. The most violent ruptures within the Taliban to date have occurred when discontented Taliban commanders from ethnic minorities have disagreed with the Pashtun-dominated leadership. The first involved an ethnic Uzbek commander in Faryab province whom the Taliban detained for a few months in early 2022. The second was an ethnic Hazara whose loyalists skirmished with Taliban forces that June after he was removed as intelligence chief of Bamyan province.

Any future struggle over leadership succession could also bring internal divisions to the fore, although this scenario also remains purely speculative.

” Hardliners among the Taliban might … feel that the leadership has gone soft, if it relaxes its ideological tenets so as to engage with regional and international actors. “

Hardliners among the Taliban might also come to feel that the leadership has gone soft, if it relaxes its ideological tenets so as to engage with regional and international actors. One of IS-KP’s main messages in recent years is that the Taliban leadership has deviated from its original vision.

So far, such criticisms have been blunted by the Taliban’s conservative decisions on social issues, such as banning teenage girls from schools (a move viewed as so retrograde that many Taliban oppose it). Little evidence suggests that the meagre compromises the Taliban is making – quietly allowing girls’ secondary schools to open in several provinces, for example – are fuelling ideological battles among the rank and file.

Factional divides could also emerge, in theory, if a large group of Taliban such as the Haqqani family from the south east were to become embroiled in fighting others such as the heavyweights from the south. Unity is deeply ingrained in the movement, however, and the leadership will likely remain attentive to the risk of splintering and be prepared to take counter-measures as needed.

If the group did nevertheless fragment for one of the foregoing reasons (or on some other basis), a return to the multi-sided civil wars of the 1990s is possible, as Taliban defectors would not necessarily join IS-KP or the NRF but instead might break off into new groups. Such a scenario could portend the disintegration of the Taliban’s authority in parts of the country, with new groups battling for their own territory.

B. Unification of Opposition Groups

Another scenario that could lead to rising violence would involve anti-Taliban groups coalescing into a more powerful insurgency that could draw the government into a broader and deadlier war. The main contenders, IS-KP and the NRF, are trying to recruit members from other armed groups and expand their operations across the country. IS-KP seeks defectors from the Taliban and other jihadist organisations, while the NRF and Afghanistan Freedom Front have been competing to build a resistance that comprises all former Republic security forces. IS-KP has also increasingly tried to recruit ethnic Tajiks and Uzbeks from Afghanistan and Central Asia.

Such efforts remain nascent. Since the Taliban seized power, IS-KP has found no support among the membership of other jihadist groups in Afghanistan, such as al-Qaeda and TTP, which do not seek confrontation with the Taliban (and, in al-Qaeda’s case, is locked in a global battle for influence with ISIS).

The NRF has struggled to broaden its appeal beyond its bastion in Panjshir, and several prominent northern commanders have refrained from throwing their weight behind it. Although the Afghanistan Freedom Front and the NRF have reportedly cooperated in a few limited cases, unification between the two seems unlikely with each group seeking to attract fighters away from the other. A merger between the High Resistance Council and the NRF is similarly unlikely, at least for now, due to squabbles over leadership. In the short term, there appears to be scant prospect of unity among the disparate groups.

C. Insurrections by Other Jihadist Groups

Afghanistan remains home to several jihadist groups, including al-Qaeda, TTP, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan and others.

Many of these groups enjoy sanctuary in Afghanistan and, reportedly, greater overall freedom under Taliban rule than under the previous government. The Taliban continue to insist that they will not allow these groups to use Afghan territory to plot or conduct attacks outside the country. The TTP, which has been accused of cross-border attacks into Pakistan, has already undermined such assurances, however.

The Taliban appear to be taking modest steps to control such groups, such as moving foreign militants away from the frontier and into Taliban heartlands to make cross-border attacks more difficult, and help the new authorities keep a more watchful eye on them.

Other precautions may include the establishment of what the Taliban call “refugee camps” to house militants and their families – reflecting the Taliban’s longstanding practice of describing Islamist fighters from other countries as political dissidents – as well as the integration of jihadists, including foreigners, into Taliban government structures. Referring to militants as refugees may also be the Taliban’s way of feigning compliance with the 2020 U.S.-Taliban agreement, which allows the Taliban to grant asylum to any individual who does not “pose a threat to the security of the United States and its allies”.

” The Taliban believe this strategy [of allowing jihadist groups to have safe haven in Afghanistan] is working, but it has serious risks. “

The Taliban believe this strategy is working, but it has serious risks.

Should the Taliban antagonise the militants, there is a small chance that one or more of the groups could rebel, which could lead to armed confrontation. Although few of these groups have the military clout to resist a Taliban crackdown, any clash could antagonise Taliban rank and file, leading to defections. On the flip side, allowing these groups to continue having safe haven in Afghanistan while taking a light-handed approach to controlling them poses at least some risk that they will engage in external operations (as the TTP is already doing), regardless of whether they have Taliban leaders’ consent, and that outsiders will intervene. That, in turn, could trigger a cascade of events: in the days following Zawahiri’s killing, for example, anti-U.S. protests were reported in several provinces.

For the time being – even after Zawahiri’s death – the new authorities appear to believe that they can sufficiently rein in such groups to address regional and international security concerns while avoiding suppressive measures that might spur a violent response.

D. External Support for Insurgents

A final scenario that could result in deteriorating security might occur if armed opposition groups receive substantial support from regional or other foreign actors. Taliban officials frequently raise this worry in meetings with external interlocutors as the primary threat to security.

The fact that regional countries sometimes highlight their warm relations with anti-Taliban groups only deepens the Taliban’s concerns.

Some regional countries do indeed have incentives to support opposition groups. For example, the Taliban’s new government largely excludes the Tajik minority, a group with which Iran and Tajikistan share historical affinities.

Neighbouring countries may see hosting Tajik political dissidents from Afghanistan as a way to nudge the Taliban toward a broader-based government. Regional countries might also feel the need to retain relationships with groups opposed to the Taliban as a hedging tactic in case of a return to civil war. Some Taliban officials argue that regional actors may seek to undermine their rule because they prefer a neighbour that is weak and amenable to others’ demands.

So far, however, there is little evidence to suggest that regional or other foreign governments are providing large-scale support to opposition groups. Senior U.S., British and European officials have privately indicated unwillingness to bankroll an armed opposition.

The British government has declared that it does not support anyone seeking to achieve political change in Afghanistan through violence. Indeed, organisers of anti-Taliban elements have complained bitterly about the lack of outside assistance.

” A negative cycle may emerge if regional actors support anti-Taliban factions as a safeguard against threats from inside Afghanistan. “

Still, the Taliban persist with their warnings that outside support for resistance groups could unsettle the country with negative implications for regional and international peace and security.

A negative cycle may emerge if regional actors support anti-Taliban factions as a safeguard against threats from inside Afghanistan, as this course of action could encourage the Taliban to align themselves more closely with transnational jihadists.

VI. Understanding and Addressing Security Concerns

A. Regional and International Concerns

Regional, Western and other foreign actors have diverse views about potential threats emanating from Afghanistan, particularly under the new Taliban government.

Each actor perceives different risks, but all of them share a high degree of concern. In many ways, managing insecurity within and coming from Afghanistan is a common international agenda.

China’s primary concern is containing potential spillover of militancy into its territory, with a strong focus on Uighur fighters.

It has engaged the Taliban authorities on this topic and there are signs the Taliban have relocated some fighters away from the Afghanistan-China border, but Taliban officials are concerned that persisting with this course might drive Uighur militants into IS-KP’s hands.

Russia, Iran and the Central Asian states are chiefly concerned with stopping IS-KP from growing stronger, although they also worry about other foreign militant groups – some of which, like the Uighur fighters, are allied with the Taliban.

While, like China, these states view the Taliban authorities as the best bet to ensure Afghanistan does not again threaten regional stability, they could eventually lose patience. The new Afghan authorities’ crackdown on IS-KP has not stopped the group from launching minor attacks on Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, and those countries are exploring options to secure their borders. Uzbek drones have allegedly flown inside northern Afghanistan, although Uzbekistan denies it. Tajikistan, according to unverified reports, may be considering acquiring U.S. drones to monitor its borders.

As for Pakistan, where levels of militant violence in the tribal areas along the Afghan border have already spiked since the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan, the rejuvenation of the TTP is its primary concern. Enjoying sanctuary under the Taliban, the TTP has launched an increasingly deadly cross-border campaign. Frustrated by the Taliban’s inaction, Pakistan has resorted to cross-border shelling and occasional airstrikes. For now, the Taliban have opted for mediation between the TTP and Pakistan instead of violently confronting the militant group, and for the time being Pakistan has accepted this approach, though the outreach has not yet produced a cessation of hostilities. TTP attacks have continued into the summer of 2022.

India has also re-engaged with the Taliban on security issues, perhaps encouraged by the latter’s tensions with Pakistan, India’s arch-rival. This re-engagement follows a long history of animosity between New Delhi and the Taliban, who, when ruling Afghanistan in the 1990s, offered safe haven to anti-India militant groups.

This time around, India seems eager to tread a different path, engaging with the Taliban government to forestall the spread of weapons and militants into Kashmir. Media have reported that the Taliban promised New Delhi to take action based on Indian intelligence against groups that threaten India, though precisely how far the Taliban would go against groups like Jaish-e-Mohammed or Lashkar-e-Tayyaba that have traditionally enjoyed tacit Pakistani patronage remains unclear. Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent continues threatening to carry out attacks on India.

” Western governments remain deeply concerned about transnational militant groups, which seem reasonably comfortable in Afghanistan since the Taliban took over. “

Finally, Western governments remain deeply concerned about transnational militant groups, which seem reasonably comfortable in Afghanistan since the Taliban took over – in the case of Zawahiri, enjoying a luxury villa once occupied by U.S.-funded organisations in Kabul.

The U.S. and its allies departed Afghanistan with the hope of managing terrorist threats from a distance. Following the Taliban takeover, the U.S. reportedly developed an over-the-horizon strike capacity but did not conduct an attack until the Zawahiri strike. Some U.S. officials suggest that the Taliban have thus far prevented al-Qaeda from rejuvenating, but they also express concern that this could change. After discovering the al-Qaeda leader on the Taliban’s doorstep, U.S. officials said they would review these evaluations.

B. The Peril of Unilateral Strikes

Against this backdrop, it might be tempting for Western or regional powers to suppress the aforementioned threats with unilateral military action in Afghanistan. Routine over-the-horizon operations are difficult without intelligence assets on the ground, as well as expensive, but U.S. officials have not ruled them out.

Yet returning to airstrikes or other attacks as a routine counter-terrorism tool would be a mistake. The U.S. is likely to strike again should it discover high-level militant leaders, like Zawahiri, in Afghanistan. But while airstrikes can kill individuals, alone they are unlikely to eradicate militant groups. The blowback could harden views on the ground and motivate a new generation of externally focused militants. Anti-Taliban jihadists – who are also a threat to other governments – are already recruiting by painting the new government as a foreigners’ puppet. Airstrikes would strengthen such narratives by raising suspicions of Taliban collusion with the West – suspicions that the Taliban would feel forced to work hard to counteract in ways that would put them in a more directly adversarial stance vis-a-vis Western governments.

Regular airstrikes could have other negative and hard-to-predict repercussions. The Taliban are themselves trying to avoid provoking the enmity of the foreign jihadists they host while discouraging them from plotting attacks abroad that would bring foreign governments’ wrath. The pitfalls in this approach are evident and the outside world is right to safeguard against it. At the same time, it is not hard to see a wider-scale campaign of airstrikes on foreign militants setting off reactions that would make things worse, whether by causing defections from the Taliban to IS-KP, by initiating other splits within the group that could trigger factional conflict or by leading the Taliban to be more indulgent of militant plotting.

Pakistan has already inflamed sentiments among the Taliban by launching airstrikes against TTP targets that generated considerable tensions between the two countries.

While the two sides were able to defuse the situation, Taliban officials say the Pakistani strikes unhelpfully precipitated discussions among the Taliban about doubling down on support for anti-Pakistan groups as a means of gaining leverage to prevent further violations of Afghan sovereignty. That could have set off a spiral of tit-for-tat actions, with Pakistan conducting more strikes and the Taliban fuelling militancy; fortunately, diplomacy has so far prevented such a negative result.

” The Taliban have asked regional and Western countries to share “actionable intelligence”, rather than acting unilaterally. “

The Taliban have asked regional and Western countries to share “actionable intelligence”, rather than acting unilaterally, although the Taliban’s willingness to follow up remains highly uncertain and foreign governments’ willingness to share information is tepid at best.

Taliban officials continue to believe they can manage such threats in a way that does not risk diminishing their control or lead to a deterioration of the security landscape in the medium term.

C. Scope for Practical Cooperation

While circumspection about the use of force is highly advisable, the outside world does not need to stay completely on the sidelines. Regional and Western governments could be well-served by a policy of pragmatic engagement on a narrow range of security issues, cooperating with the Taliban on some practical challenges for the sake of promoting stability in ways that benefit the Afghan population, and seeking greater fulfilment of the Taliban’s prior security commitments in the bargain. Though it is difficult to contemplate so close on the heels of the Zawahiri strike, some scope remains for working with the Taliban on security issues – even for Western countries, which profoundly mistrust the Taliban. Outsiders might derive benefits from this sort of limited engagement, such as being able to more closely monitor the evolving landscape. The engagement might also build the confidence that would be necessary for any conceivable deeper cooperation, although such a positive outcome remains a distant prospect for the moment.

Senior Taliban officials’ continued insistence that their government is bound by the 2020 Doha agreement might help enable pragmatic engagement. The U.S. and the Taliban have accused each other of violating this accord, which paved the way for the withdrawal of U.S. troops.

The Taliban’s clumsy obfuscations about al-Qaeda, and the cross-border attacks by IS-KP, raise serious questions about whether they are willing or able to keep their end of the deal. Still, the agreement should, in theory, define the Taliban’s responsibilities for preventing terrorism and U.S. commitments not to conduct strikes on Afghan territory. Revising the text would be a mistake, as it would open a Pandora’s box, but talks about how to implement the deal would be timely. The U.S. envoy who made the deal has said it has secret annexes containing benchmarks for evaluating the Taliban’s performance; such an evaluation might lead to greater clarity on both sides.

Although the agreement is not enforceable, both sides have used it as a reference point for mutual expectations, suggesting they wish to keep it alive as a set of benchmarks.

Should modest collaboration be in the cards – and some Western officials hope that such measures are still possible, after Zawahiri’s death – small practical steps to make Afghanistan a safer place for Afghans and prevent the spillover of insecurity into its neighbourhood would be a good place to start.