Introduction: The Islamic State’s Sahelian Affiliate

The Islamic State Sahel Province (IS Sahel) is a salafi-jihadist militant group and the Sahelian affiliate of the transnational Islamic State (IS) organization. It is primarily active in the border areas between Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger — known as the tri-state border area, or Liptako-Gourma — but it has also engaged in sporadic activity in Algeria, Benin, and Nigeria. The group’s composition reflects the social fabric in the areas where it is active. Its members belong to the Fulani, Arab, Tuareg, Dawsahak, Songhai, and Djerma ethnic groups, although its core leadership was historically composed of Western Saharan militants.

The genealogy of IS Sahel goes back more than a decade and is the result of a series of mergers and splits. Its de facto predecessor, the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (better known by its French acronym, MUJAO), was formed in 2011 as an offshoot of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and gathered Sahelian Arabs from Mali, Mauritania, and Western Sahara. MUJAO was initially involved in a series of kidnappings of Westerners in southern Algeria, but rose to prominence during the jihadist takeover of northern Mali in 2012, ruling northern Mali’s largest city, Gao, for about six months. Then, in August 2013, MUJAO merged with Signatories in Blood, led by the notorious Algerian militant commander Mokhtar Belmokhtar, to form al-Mourabitoun. Western Saharan Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahrawi, the former MUJAO spokesman who became the head of al-Mourabitoun’s Shura Council, eventually defected along with his men from al-Mourabitoun after swearing allegiance to the IS and its then-leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, in May 2015.1

After its formation in May 2015, the group went through several phases in its wartime transformation until it was granted ‘provincial’ status in March 2022. Initially, IS Sahel was known as the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS). The group did not carry out attacks, or at least did not claim responsibility for them, until September 2016, when it began to carry out a series of attacks on military and security force positions in Burkina Faso and Niger. These attacks included a raid on a customs post in Markoye, an attack on a military camp in Intagom, and a failed prison break in Koutoukale. The string of attacks apparently caught the Islamic State Central’s (IS Central’s) attention as it belatedly took note of the pledge of allegiance by diffusing a video from the ceremony via its Amaq newswire. Some observers frowned upon the relatively small size of the ISGS, which at its inception was estimated to have consisted of only a few dozen men and owned no more than a handful of pickup trucks.2

Between March 2019 and March 2022, IS Sahel was technically the Greater Sahara faction of the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) as part of the IS organizational infrastructure before being declared a separate province in March 2022. For the sake of clarity, in this report, the group will be referred to by its latest iteration, IS Sahel.

Activity and Area of Operations

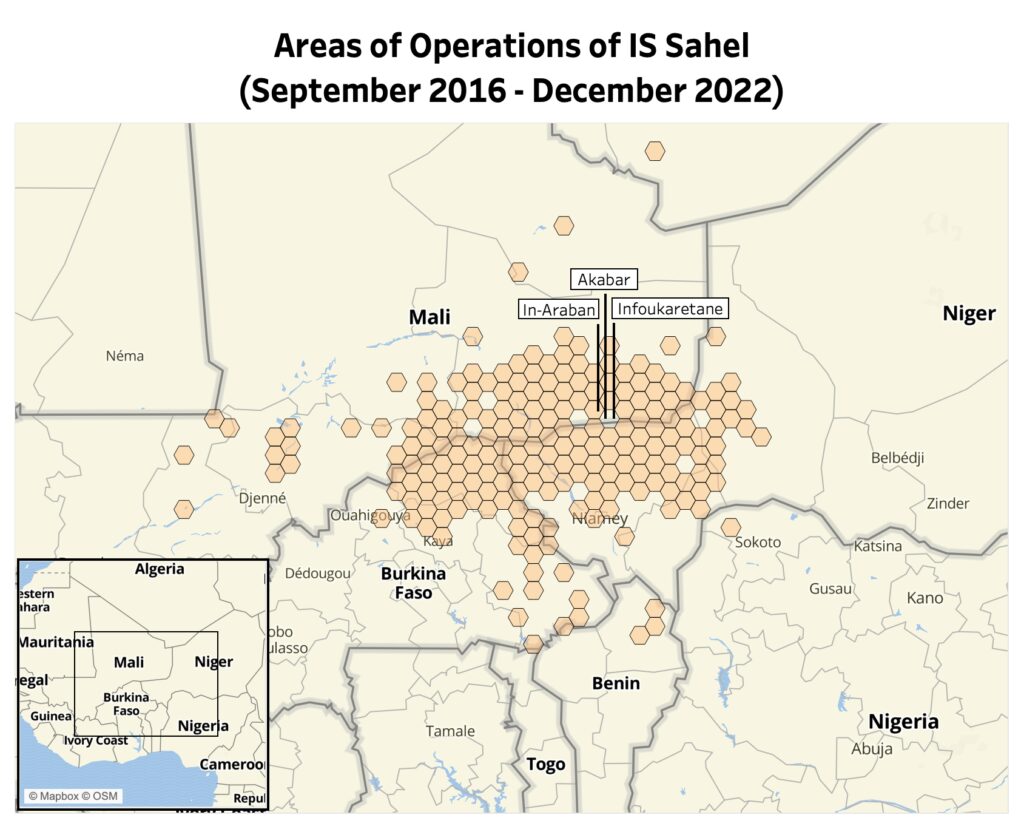

IS Sahel is the second most active armed actor — after its al-Qaeda rival Jamaa Nusra al-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM) — in the Sahel regional conflict. From its strategic home in the border area between Mali and Niger, where villages such as In-Araban, Akabar, and Infoukaretane are important bases (see map below), IS Sahel operates primarily in the Liptako-Gourma area. The group has become the dominant actor in several of the regions encompassing this area, including the Gao and Menaka regions in Mali, the Oudalan and Seno provinces in Burkina Faso, and the Tillaberi and Tahoua regions in Niger, as well as areas adjacent to the aforementioned regions.

For most of IS Sahel’s existence and throughout the period between 2015 and 2019, when it was known as the ISGS, its ties to the IS Central were tenuous at best. Despite this apparent public disconnect, manifested by the ISGS’s absence from IS media operations, the violence and brutality exhibited by the group demonstrated both its continued loyalty and willingness to align with the parent organization. This tenuous link changed in March 2019, when the group was formally integrated into the IS organizational infrastructure as the separate Greater Sahara faction of ISWAP.3

The integration of the group as an independent wing of ISWAP occurred against the backdrop of militant expansion of the group and JNIM throughout the Sahel region.4 In the period following the ISWAP incorporation, a major change in IS Sahel’s capabilities was observed when the group attacked and overran numerous military positions in the Liptako-Gourma area over the course of a year between May 2019 and May 2020, reportedly killing more than 400 soldiers from Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger (see graph below).

The violent campaign was apparently driven by growing competition between IS Sahel and JNIM, as the former sought to challenge the dominance of its al-Qaeda counterpart, which for years had been an ally facing common opponents among international forces, local government troops, and pro-government militias. In response to the growing lethality of IS Sahel and the apparent inability of government forces to effectively resist the group, France directed extensive military operations to contain the growing threat from IS Sahel (for more, see this ACLED report). During a military campaign conducted between early 2020 and mid-2021 against the group, IS Sahel suffered significant attrition, and its historical Western Saharan core leadership was largely decimated. Among those killed during this campaign was IS Sahel founder Abu Walid al-Sahrawi, who was killed in a French military airstrike in the forest of Dangarous on 17 August 2021.

However, as with previous military campaigns against IS Sahel, these operations were accompanied by indiscriminate violence by local state forces that left hundreds of civilians dead in a matter of months. Moreover, government forces were never able to recapture lost territory and re-establish a sufficient permanent presence. Rather, the area would become an important battleground in a full-fledged turf war between IS Sahel and JNIM, as both vie for influence and dominance in the tri-state border region.5

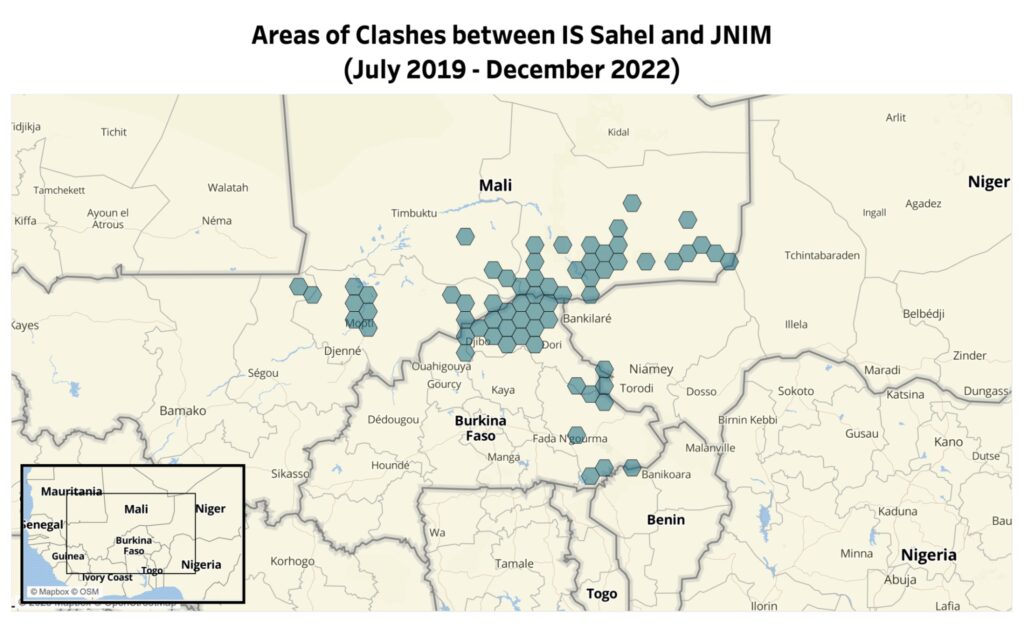

The conflict between IS Sahel and JNIM has become particularly deadly and protracted, with nearly 200 reported clashes resulting in more than 1,100 combatants killed since fighting broke out in mid-2019. While JNIM gained ascendency in 2020, the tide has turned in favor of IS Sahel in recent months, as IS Sahel fighters inflicted significant losses in JNIM ranks in a series of major battles in the Gao and Menaka regions and along the border between Burkina Faso and Mali between September and November 2022 (see map below). This allowed IS Sahel fighters to return to areas where they had been largely absent after being pushed out by JNIM during the 2020 fighting.

Other sporadic IS Sahel activity has also been recorded in neighboring Algeria, Benin, and Nigeria. In Algeria, IS Sahel was involved in a handful of events in 2019 and 2020 after attempting to regain a foothold in areas where its predecessor, MUJAO, had been present in 2011-12. Activities in Algeria have been driven by a plan to expand operations outside the group’s traditional stronghold in the tri-state border area, apparently attempting to establish a coordination center by joining forces with Libyan fighters and possibly making a short-lived attempt to revive the defunct Islamic State Algeria Province.

A short stint of activity in northwestern Nigeria in 2019 is explained by several factors. First, the road between Sanam, Dogondoutchi, and Sokoto is an important supply route for the group.6 Second, fighters from IS Sahel arrived in Sokoto in 2018 and 2019 to help communities with which they have kinship ties against banditry.7 Third, northwestern Nigeria provided recruitment opportunities as IS Sahel militants sought to expand operations. Their fighters operating there at the time were locally referred to in the Hausa language as “Lakurawa” (the recruits).8

Meanwhile, activities in Benin are more recent, as IS Sahel claimed two operations in the department of Alibori in July 2022. According to IS Sahel’s own propaganda, this was part of the group’s continued expansion into new areas. However, IS Sahel’s activities in Benin likely predate the claimed operations but remain largely covert in nature. The announced presence of IS Sahel in Benin follows in the footsteps of a broader and accelerated militant expansion throughout the Sahel and northern parts of the West African littoral states. While both IS Sahel and JNIM have simultaneously moved into new areas in recent years, IS Sahel fighters have had difficulty maintaining and consolidating their presence in these areas, as seen in the East and Center-North regions of Burkina Faso and in central Mali. Nevertheless, they have managed to establish dominance in their traditional strongholds and expand their influence in adjacent areas. It remains to be seen whether Benin will become an exception to the prevailing trend.

Pattern of Violence and Activities

IS Sahel militants exhibit a distinct pattern of conflict characterized by large-scale violence against a variety of adversaries and civilians. An important aspect of IS Sahel’s violence is that it tends to be indiscriminate: IS Sahel does not distinguish between combatants and civilian communities among opposing forces. As such, IS Sahel militants have repeatedly engaged in episodes of mass violence against military forces, militias, rival militants, and civilians in the countries where they primarily operate.

The first episode of such violence came in retaliation for operations by French-backed militias in 2018 and targeted various Tuareg and Dawsahak communities in the Menaka region of Mali. In neighboring Burkina Faso, they also perpetrated a large series of massacres against Mossi, Foulse, Songhai, and Bellah communities in the Sahel and Center-North region between 2019 and 2021, coinciding with the aforementioned offensive against government troops in the three central Sahel countries from mid-2019 to early 2020. In Niger, IS Sahel perpetrated widespread mass atrocities against ethnic Djerma and Tuareg communities in the Tillaberi and Tahoua regions and engaged in deadly confrontations with Djerma and Tuareg militiamen from the then-fledgling self-defense militias, which formed in response to IS Sahel’s excessive violence and predatory activities in the Tillaberi and Tahoua regions. In March 2022, coinciding with its designation as a stand-alone province, the group launched an offensive in the Menaka and Gao regions on an unprecedented scale. During the six-month offensive between March and August 2022, more than a thousand people were killed, including civilians, pro-government Movement for the Salvation of Azawad and the Imghad Tuareg Self-Defense Group and Allies militiamen, and rival JNIM fighters.

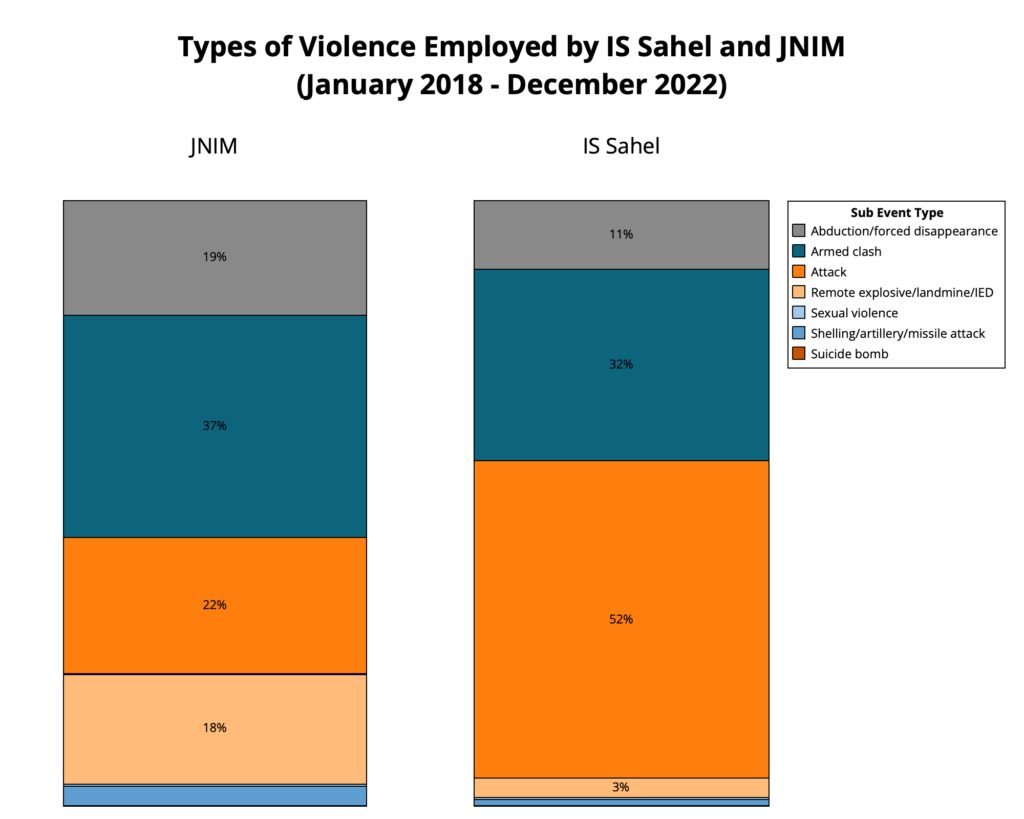

Another dimension that distinguishes IS Sahel from its al-Qaeda counterpart concerns the strategy and tactics that they employ. IS Sahel’s preferred modi operandi are ambushes and swarming tactics through motorcycle and vehicle-borne armed assaults, while JNIM employs an overwhelmingly higher proportion of remote violence from a distance through the use of explosives, artillery, and mortar fire, tactics that IS Sahel fighters rarely employ (see graph below).

Apart from the violent activities of IS Sahel, resource extraction through cattle theft, extortion, and the collection of zakat (alms or taxes) represent an important dimension of the group’s repertoire. However, IS Sahel’s jihadist rival, JNIM, outdoes it threefold in terms of such activities.

Looking Forward

Alongside the death of IS Sahel’s founding leader Abu Walid al-Sahrawi, the largely Sahrawi core leadership of IS Sahel has been decimated. However, a new emir, Abu al-Bara al-Sahrawi, along with a cadre of local commanders, has replaced the previous leadership, some of whom were already seasoned fighters and had been groomed for years to take over and provide continuity along with new generations of fighters. Political conditions have further developed in favor of IS Sahel as the French-led regional counterterrorism alliance eventually broke up following successive coups in Mali and Burkina Faso.

Evidently, the rise in power of IS Sahel has coincided with the withdrawal of French forces from Mali, which began in mid-2021. The combined forces currently present in Mali, including the Malian armed forces, the Wagner Group, JNIM fighters, and various militias and former rebel groups, have not been able to deter or contain IS Sahel’s violence. Isolated and haphazard alliances have formed at the local level, but the hostility and divergent interests of the various armed actors opposing IS Sahel make a major joint effort unlikely. Until government forces and the various armed groups in the region make a concerted effort to confront the group, IS Sahel will likely continue its onslaught.

Indeed, IS Sahel is in the process of establishing a pseudo-state encompassing the rural areas stretching from Gao in the north to Dori in the south and from N’Tillit in the west to the border area of Tahoua in the east. Several towns, including Anderamboukane, Indelimane, and Tin Hama, to name a few, serve as quasi-administrative capitals of the IS Sahel pseudo-state, which is gradually taking shape. IS Sahel militants will seek to assert their influence through large-scale violence and expand operations in areas where they face weak opposition, while operating in a chaotic conflict environment characterized by a multitude of armed actors who have thus far proven unable, either on their own or in coalitions, to contain IS Sahel.