Many decades ago, the Americans proposed to use nuclear weapons to blast a waterway through the Negev Desert. But the plan never progressed. This is why it did not — and why there is some talk about the ‘Ben Gurion Canal’ again as Israel pushes to destroy Hamas in Gaza

It has been speculated that one of the reasons behind Israel’s desire to eliminate Hamas from the Gaza Strip and completely control the Palestinian enclave is to give itself the chance to better explore a dramatic economic opportunity that has been talked about for several decades, but for which peace and political stability in the region is an essential prerequisite.

The idea is to cut a canal through the Israeli-controlled Negev Desert from the tip of the Gulf of Aqaba — the eastern arm of the Red Sea that juts into Israel’s southern tip and south-western Jordan — to the Eastern Mediterranean coast, thus creating an alternative to the Egyptian-controlled Suez Canal that starts from the western arm of the Red Sea and passes to the southeastern Mediterranean through the northern Sinai peninsula.

This so-called Ben Gurion Canal Project, which was first envisioned in the 1960s would, if it were to be actually completed, transform global maritime dynamics by taking away Egypt’s monopoly over the shortest route between Europe and Asia.

However, any attempt to construct the canal would have to overcome gigantic logistical, political, and funding challenges which, in the current situation, makes it seem largely fantastical. We take a look at what has been proposed, and its implications, theoretically, on global trade and geopolitics.

But first, a look at the Suez Canal’s salience.

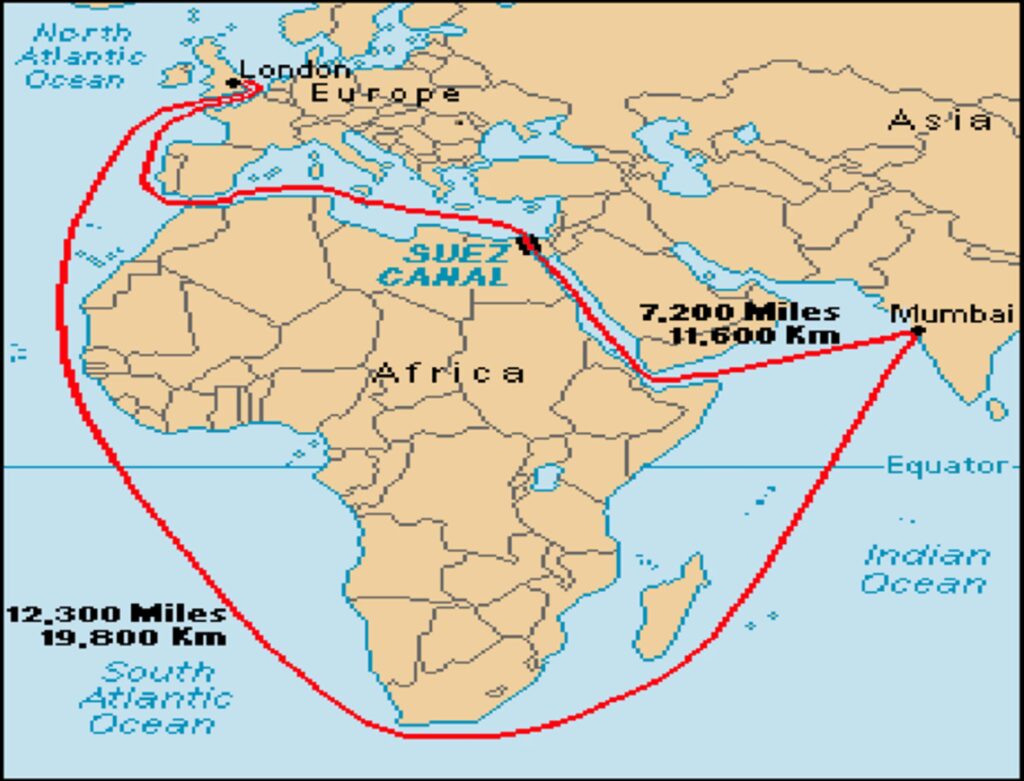

When it opened in 1869, the Suez Canal revolutionised global maritime trade. By connecting the Mediterranean and Red Seas through the Isthmus of Suez, it ensured that ships travelling between Europe and Asia would not have to travel all the way around the continent of Africa. The canal cut the distance between London and Bombay (now Mumbai) by a more than 41 per cent.

In the 2022-23 fiscal year, around 26,000 vessels crossed the Suez Canal, accounting for approximately 13 per cent of global shipping.

The canal, however, has its issues.

First, the 193 km-long, 205 m-wide, and 24 m-deep Suez Canal is the world’s biggest shipping bottleneck. Despite being widened and deepened over the years, it remains perennially congested, with long queues at either end. In March 2021, the mammoth cargo ship Ever Given got stuck in the canal, blocking passage for more than a week. It was estimated that the resulting “traffic jam” held up an estimated $ 9.6 billion of goods every day.

Also, Egypt’s control over the waterway has been a source of conflict for almost 70 years now. In 1956, after President Gamal Abdel Nasser (1918-70) decided to nationalise the canal, war broke out, with the UK, France, and Israel attacking Egypt in order to regain control.

The Suez Crisis ended in a military victory for the aggressors but an overwhelming political victory for Egypt, which kept control over the canal, which was shut for more than six months due to the conflict. This was also a pivotal moment in the Cold War, with Soviet threats of intervention key to stopping the allied aggression against Egypt.

The Suez Canal was also the focal point of both the 1967 and 1973 Arab-Israeli wars, and was shut from 1967-75.

The canal is, of course, critical to Egypt’s economy. It collects all the toll revenue generated, in addition to the benefits it brings to its local economy. In the 2022-23 fiscal year, Egypt’s Suez Canal Authority saw toll revenues reach a record $ 9.4 billion — accounting for nearly 2 per cent of Egypt’s GDP of $ 476.8 billion, according to the World Bank.

Thus, for the West, a shipping lane through Israel would be ideal.

It remains unclear when the first concrete plan for the alternative was suggested. The documented evidence can be seen in a declassified 1963 US government memorandum. The memo called for the use of nuclear explosives to dig the canal through the Negev Desert in Israel.

“Another interesting application of nuclear excavation would be a sea level canal 160 miles long across Israel, connecting the Mediterranean with the Gulf of Aqaba (and thus the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean). Such a canal would be a strategically valuable alternative to the present Suez Canal and would probably contribute greatly to the economic development of the surrounding area,” the memo reads.

The Ben Gurion Canal Project, named after Israel’s founding father David Ben-Gurion (1886-1973), remains one of the most ambitious infrastructure projects ever planned on paper.

What has stopped Israel from constructing the canal?

First and foremost, such a project would be extremely complex and almost prohibitively expensive. The estimated cost of such a project may be as high as the $ 100 billion, much more than what it might take to widen the Suez Canal and solve its traffic problem.

According to the previous cited memo, it was the cost of digging such a canal conventionally that made planners look at the nuclear option. Of course, the risk of nuclear fallout makes this option extremely risky as well.

Costs aside, the planned route of the Ben Gurion Canal is over 100 km longer than the Suez Canal, primarily due to limitations of the terrain and topography. Even if built, many ships might still favour the older, shorter route.

Most importantly, however, a canal which will potentially transport billions of dollars worth of freight daily cannot run in land under constant military threat, from Hamas rockets or Israeli attacks.