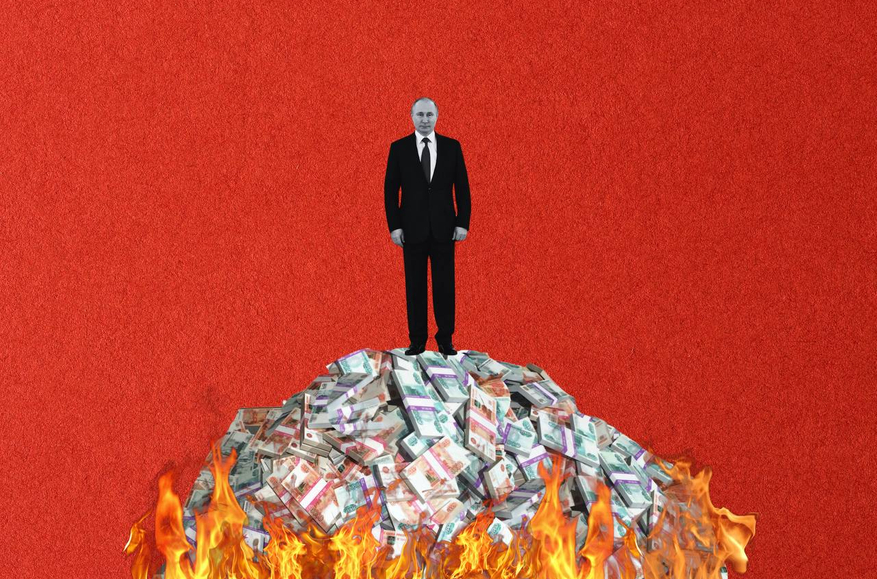

The Russian budget has been in deficit since the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and the draft budget for 2025 also envisages a deficit of 1.1 trillion rubles (0.5% of GDP). For now, the hole is being covered by current borrowing, and the National Welfare Fund (NWF) account looks impressive, but if you take a closer look, in reality, most of it is already illiquid assets that cannot be sold quickly. This means that in the event of a crisis scenario (according to the Central Bank’s calculations, this is a drop in oil prices to $55 per barrel of Brent), the fund will not save the Russian economy and will be exhausted in just a few months.

The “pillow” appears and disappears

For the first time, Vladimir Putin announced that Russia should separate its excess oil revenues into a separate direction in the second year of his presidency in his message to the Federal Assembly “On the Budget for 2002”. The author of the idea was said to be Andrei Illarionov, the then presidential adviser. Initially, Putin proposed creating not a separate fund, but two budgets – a base budget, which is based on a low oil price, and an additional one, which the country can afford if the prices are higher. But the Finance Ministry never created two budgets, and since 2004 the idea has been transformed into a Stabilization Fund – a financial reserve, where all excess revenues would be accumulated, that is, everything earned when the Urals price is higher than $20 per barrel.

The ideologist of this financial safety cushion, then Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin, drew biblical analogies. “Joseph came to the ruler of Egypt, and he needed to explain the ruler’s dreams. And he explained the famous dream that seven skinny cows and seven fat cows were grazing in one meadow. No one from the ruler’s entourage could explain this, but he explained that Egypt was expecting seven rich, fruitful years and seven years when there would be no harvest. He proposed collecting taxes and accumulating a grain fund that would help in difficult years,” Kudrin said in 2008. In essence, he explained, “this is a parable about the Stabilization Fund,” but “also about the cyclical development of the global economy.”

The very fact that the excess profits are not spent but go into the piggy bank has become the subject of constant criticism of the Ministry of Finance. Kudrin’s department was especially criticized for the fact that the Stabilization Fund’s money was kept in foreign securities, mainly in American bonds. “You have practically robbed the country – trillions of rubles have gone down the drain, don’t bother us, you had no right to send money abroad,” LDPR leader Vladimir Zhirinovsky told Kudrin during a Duma session. “Why not invest these funds in human capital, acquiring modern foreign equipment for our healthcare, education, and science?” deputy Nikolai Bezborodov echoed .

Despite the fact that the Stabilization Fund allegedly pumped money out of the Russian economy and invested it abroad, in 2004-2008 it grew much faster than ever afterwards. In addition, the ruble strengthened against the dollar. In the four years of the Stabilization Fund’s existence, Russia’s GDP, expressed in current dollars, tripled. This had never happened before or since. During this time, the state accumulated almost four trillion rubles in the Stabilization Fund, which at that time amounted to a solid 8.5% of GDP. The Stabilization Fund was spent on paying off foreign debt and on pension transfers. And everything that was left was invested. The rules for managing the fund were simple and strict: it was allowed to invest only in foreign currency accounts (45% in dollars, 45% in euros and 10% in British pounds) and in first-class government bonds of some developed countries. Naturally, there was no question that some part of this portfolio could be illiquid or of poor quality.

The second chapter in the history of Russian sovereign funds began on February 1, 2008 and lasted almost 10 years. At that time, Russia simultaneously had the Reserve Fund and the National Welfare Fund, which emerged from the Stabilization Fund, which was divided into unequal parts. 80% of assets (3 trillion rubles) were transferred to the Reserve Fund, and 20%, respectively, to the National Welfare Fund. Officially, the division was explained by new tasks. After six years of accumulation, it became possible to spend the funds more actively: the Reserve Fund served as the government’s near-term reserve, and the National Welfare Fund as a distant reserve. It was planned that the former would be needed to replenish the budget in deficit years, and the latter – it was initially planned to be called the Fund for Future Generations – to co-finance voluntary pension savings, as well as to cover the budget deficit of the pension fund.

After six years of accumulation, it became possible to spend the funds more actively

The replenishment scheme gave priority to the Reserve Fund. Excess income was first sent there and only after more than 10% of GDP had accumulated there (later the bar was lowered to 7%), it went to the National Welfare Fund, the funds from which could be invested in more risky, and perhaps obviously unprofitable, undertakings.

The Reserve Fund’s investments were to be subject, with some relaxations, to the same strict rules as the Stabilization Fund. And for the National Welfare Fund, the Budget Code immediately introduced permission to invest in “debt obligations and shares of legal entities” and in “shares (interests) of investment funds.” “The role of the National Welfare Fund in solving social problems is currently extremely small,” experts from the Gaidar Institute noted in 2010. “Moreover, the National Welfare Fund is obviously not playing the role assigned to it, but not institutionally and legislatively supported, of a tool for solving long-term problems of the pension system in Russia.” In 2013, Putin allowed part of the National Welfare Fund to be spent on infrastructure projects (40%, but no more than 1.7 trillion rubles, plus 10% each for projects of the Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF) and Rosatom).

Soon the system finally broke down. The financial crisis and low oil prices meant that the funds stopped being replenished. The year 2014 was especially serious, when the West imposed sanctions for the annexation of Crimea and a barrel of oil depreciated by half. The budget deficit forced active spending of the accumulated funds, and in 2015 the Ministry of Finance allowed the budget to be financed directly from the funds. Within a few years, the Reserve Fund was almost completely spent, and in 2018 its remains were merged into the National Welfare Fund. Thus ended the era of two funds .

After the start of the full-scale invasion, the NWF deflated sharply again: the part that can be quickly used has decreased by three trillion rubles, and now it contains 5.3 trillion (the size of the NWF has decreased from 7.2% to 2.8% of GDP). The budget deficit planned for 2025 (1.1 trillion rubles, or 0.5% of GDP) seems to be smaller, but the situation may change dramatically if the government’s rather optimistic forecasts do not come true (it is counting on the price of Russian oil at $69.7 per barrel and GDP growth of 2.5% with inflation at 4.5%). The main problem with the NWF is that most of it is illiquid and will be useless in the event of a sudden crisis.

Useless illiquid asset

Currently, the NWF contains just under 13 trillion rubles, or 6.7% of GDP. This is almost as much as the federal budget is going to spend on the war in 2025. However, not all of the NWF can be easily spent. The liquid part contains 5 trillion rubles, mainly in yuan and gold, which the Finance Ministry sells as needed. Given the dynamics of recent years, this part could be exhausted in two to three years in the inertial scenario. The Bank of Russia admits that this (liquid) part of the NWF could be exhausted even during 2025 if a risky scenario is realized (for example, a decrease in commodity prices from $70 to $55 per barrel of Brent oil).

And then we will have to turn to the illiquid part (this is 60% of the entire fund), which is invested, or, more honestly, spent on supporting a wide variety of projects. Almost a quarter of all the fund’s money, 3 trillion rubles, is invested in Sberbank shares, another 722 billion rubles are in Russian Railways preferred shares, 690 billion are on deposits in VEB.RF, 492 billion are in Russian Highways bonds, several hundred billion each are in shares of VTB and GPB banks, Aeroflot, DOM.RF, in Rostec bonds, JSC GTLK and completely non-public structures: NLK-Finance LLC, Aviacapital-Service LLC, PPK Territory Development Fund. Behind all these names are specific projects of varying degrees of economic efficiency.

Such investments would be unthinkable for a normal sovereign wealth fund with strict rules, like the Norwegian one, or even for the Russian Stabilization Fund of Kudrin’s time.

For example, 160 aircraft blocked at the beginning of the war by foreign owners (in Russia they were leased) were bought out using 300 billion rubles from the National Welfare Fund . The money was received by OOO NLK-Finance, a subsidiary of the state-owned Administration of Civil Airports (Aerodromes). The state-owned JSC GTLK, which received another 152 billion rubles, is also engaged in aircraft leasing. Aircraft are commercial assets capable of generating income; they are an investment subject, but too risky for a state fund to engage in it. But the companies’ bonds themselves are unlikely to ever be repaid or bought back by these enterprises. Therefore, with conservative planning, it is better to take the illiquid part of the National Welfare Fund as zero.

In conservative planning, it is better to take the illiquid part of the National Welfare Fund as zero.

Tricks without insurance

If political decisions had been made in favor of budget discipline, openness, fair competition, and a peaceful policy with respect for neighbors, the accumulation of reserves could have continued and provided the budget with an additional source of income unrelated to taxation. Careful management of a portfolio of reliable foreign bonds is a simpler task than monitoring the effectiveness of investments in infrastructure and other projects.

But this did not happen. And such treatment of the National Welfare Fund will have quite clear consequences for the budget and for the Russian economy.

Firstly, the National Welfare Fund cannot become the main donor to the budget – there are not many funds in its liquid part (2.8% of GDP). The government has so far managed to use other methods of financing a moderate deficit (less than 2% of GDP by the end of 2024, as the Ministry of Finance expects ). First of all, these are internal borrowings, as well as the withdrawal of money from state-owned enterprises. At the same time, the National Welfare Fund’s funds are still important for the not very efficient enterprises and projects in which it invests, and for many personally interested persons behind them.

Secondly, the dynamics of the NWF assets will most likely be inertial, that is, over time it will simply run out . It is unlikely that the fund will be completely exhausted in 2025, but it may lose weight by several more trillions and be completely exhausted within 2-3 years.

The Ministry of Finance does not expect such a scenario yet and even expects to save a little – so that the liquid part would be 5.5 trillion rubles by the end of 2025 and 9.3 trillion by the end of 2027. But this can only happen if everything goes well for Russia: the price of oil stays above $70, and then at least $66 per barrel, military spending stops growing (which is still growing steadily and quickly every year), etc. But in the opposite scenario, that is, in the case of truly serious crisis phenomena in the economy and a sharp increase in the budget deficit, the National Welfare Fund will no longer be able to play the role for which reserve funds were originally conceived in the early 2000s.