A peaceful uprising against the president of Syria almost eight years ago turned into a full-scale civil war. The conflict has left more than 360,000 people dead, devastated cities and drawn in other countries.

Even before the conflict began, many Syrians were complaining about high unemployment, corruption and a lack of political freedom under President Bashar al-Assad, who succeeded his father, Hafez, after he died in 2001.

In March 2012, pro-democracy demonstrations erupted in the southern city of Deraa, inspired by the “Arab Spring” in neighbouring countries.

When the government used deadly force to crush the dissent, protests demanding the president’s resignation erupted nationwide.

The unrest spread and the crackdown intensified. Opposition supporters took up arms, first to defend themselves and later to rid their areas of security forces. Mr Assad vowed to crush what he called “foreign-backed terrorism”.

The violence rapidly escalated and the country descended into civil war.

How many people have died?

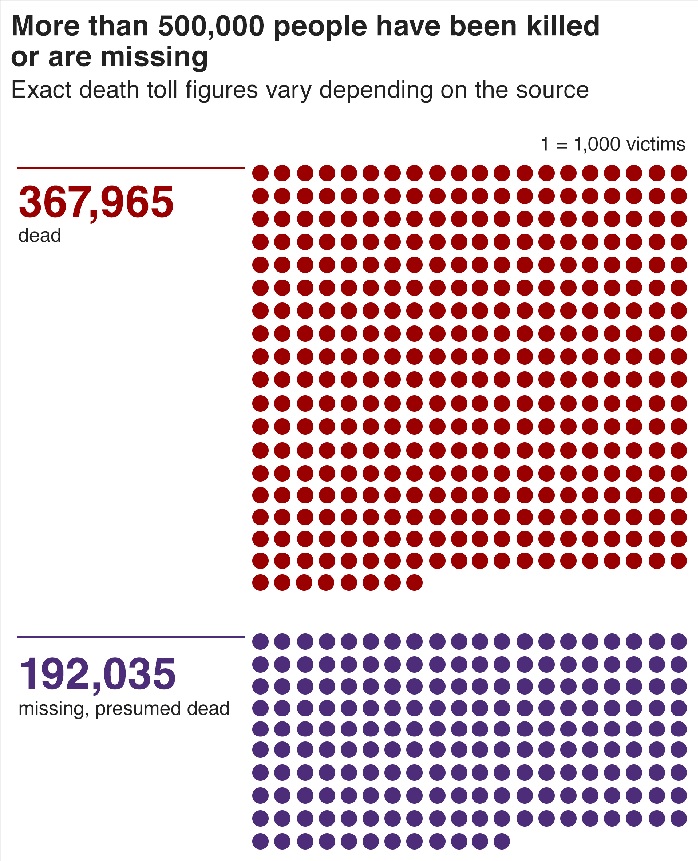

The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, a UK-based monitoring group with a network of sources on the ground, had documented the deaths of 367,965 people by December 2019.

The figure did not include 192,035 people who it said were missing and presumed dead.

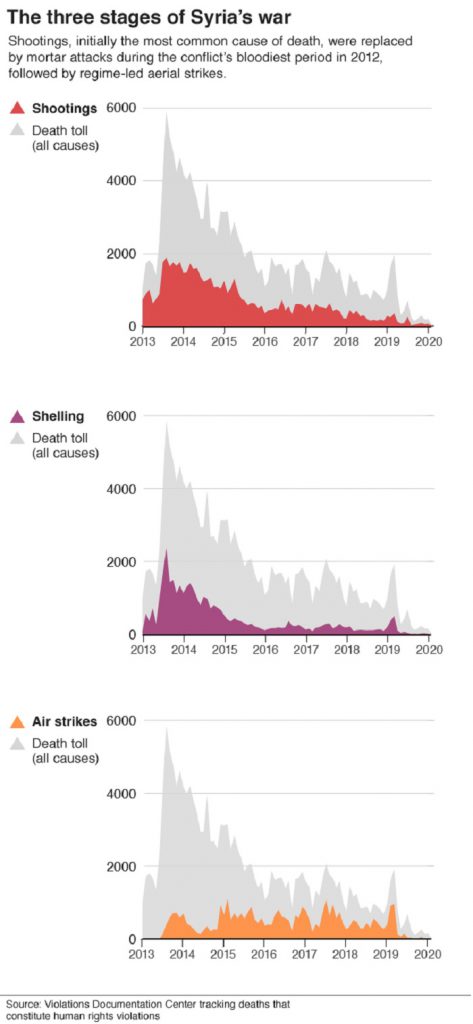

Meanwhile, the Violations Documentation Center, which relies on activists inside Syria, has recorded what it considers violations of international humanitarian law and human rights law, including attacks on civilians.

It had documented 191,219 battle-related deaths, including 123,279 civilians, as of December 2019.

What is the war about?

It is now more than a battle between those who are for or against Mr Assad.

Many groups and countries – each with their own agendas – are involved, making the situation far more complex and prolonging the fighting.

They have been accused of fostering hatred between Syria’s religious groups, pitching the Sunni Muslim majority against the president’s Shia Alawite sect.

Such divisions have led both sides to commit atrocities, torn communities apart and dimmed hopes of peace.

They have also allowed the jihadist groups Islamic State (IS) and al-Qaeda to flourish.

Syria’s Kurds, who want the right of self-government but have not fought Mr Assad’s forces, have added another dimension to the conflict.

Who’s involved?

The government’s key supporters have been Russia and Iran, while Turkey, Western powers and several Gulf Arab states have backed the opposition.

Russia – which already had military bases in Syria – launched an air campaign in support of Mr Assad in 2016 that has been crucial in turning the tide of the war in the government’s favour.

The Russian military says its strikes only target “terrorists” but activists say they regularly kill mainstream rebels and civilians.

Iran is believed to have deployed hundreds of troops and spent billions of dollars to help Mr Assad.

Thousands of Shia Muslim militiamen armed, trained and financed by Iran – mostly from Lebanon’s Hezbollah movement, but also Iraq, Afghanistan and Yemen – have also fought alongside the Syrian army.

The US, UK and France initially provided support for what they considered “moderate” rebel groups. But they have prioritised non-lethal assistance since jihadists became the dominant force in the armed opposition.

A US-led global coalition has also carried out air strikes on IS militants in Syria since 2015 and helped an alliance of Kurdish and Arab militias called the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) capture territory once held by the jihadists in the east.

Turkey has long supported the rebels, but it has focused on using them to contain the Kurdish militia that dominates the SDF, accusing it of being an extension of a banned Kurdish rebel group in Turkey. Turkish-backed rebels have controlled territory along the border in north-western Syria since 2017.

Saudi Arabia, which is keen to counter Iranian influence, has armed and financed the rebels, as has the kingdom’s Gulf rival, Qatar.

Israel, meanwhile, has been so concerned by what it calls Iran’s “military entrenchment” in Syria and shipments of Iranian weapons to Hezbollah that it has conducted hundreds of air strikes in an attempt to thwart them.

How has the country been affected?

As well as causing hundreds of thousands of deaths, the war has left 1.5 million people with permanent disabilities, including 86,000 who have lost limbs.

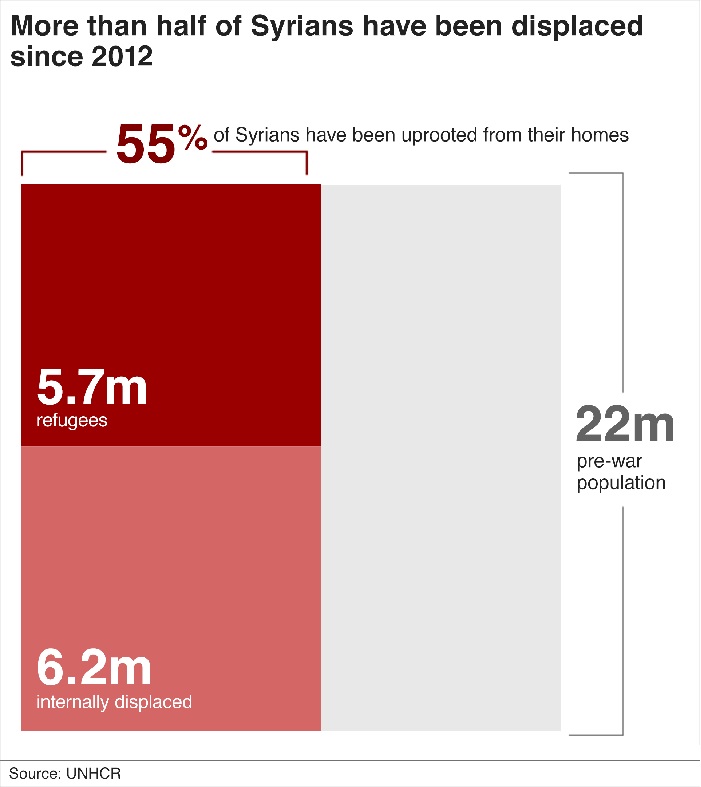

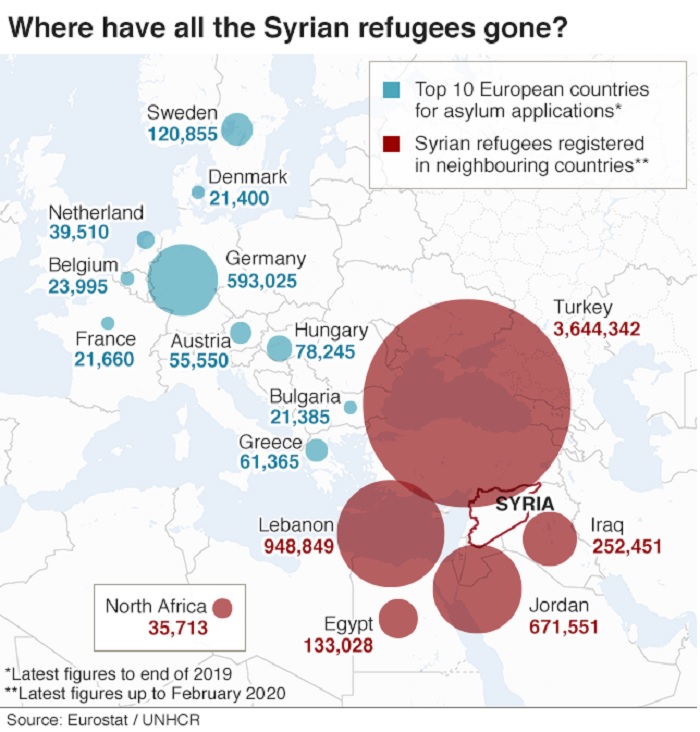

At least 6.2 million Syrians are internally displaced, while another 5.7 million have fled abroad.

Neighbouring Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey, which are hosting 93% of them, have struggled to cope with one of the largest refugee exoduses in recent history.

By February 2020, some 13 million people were estimated to be in need of humanitarian assistance, including 5.2 million in acute need.

The warring parties have made the problems worse by refusing aid agencies access to many of those in need. Some 1.1 million people were living in hard-to-reach areas as of February 2020.

Syrians also have limited access to healthcare.

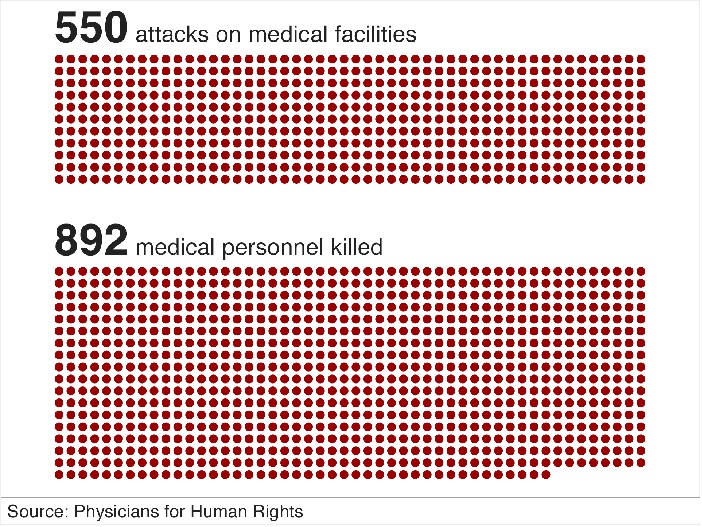

Physicians for Human Rights had documented 550 attacks on 384 separate medical facilities by December 2019, resulting in the deaths of 892 medical personnel.

Much of Syria’s rich cultural heritage has also been destroyed. All six of the country’s six Unesco World Heritage sites have been damaged significantly.

Entire neighbourhoods have been levelled across the country.

In one district in the Eastern Ghouta – a former rebel bastion outside Damascus – 93% of buildings had been damaged or destroyed by December 2018, according to UN satellite imagery analysis. The government’s six-week ground offensive that began in February 2019 caused further destruction.

How is the country divided?

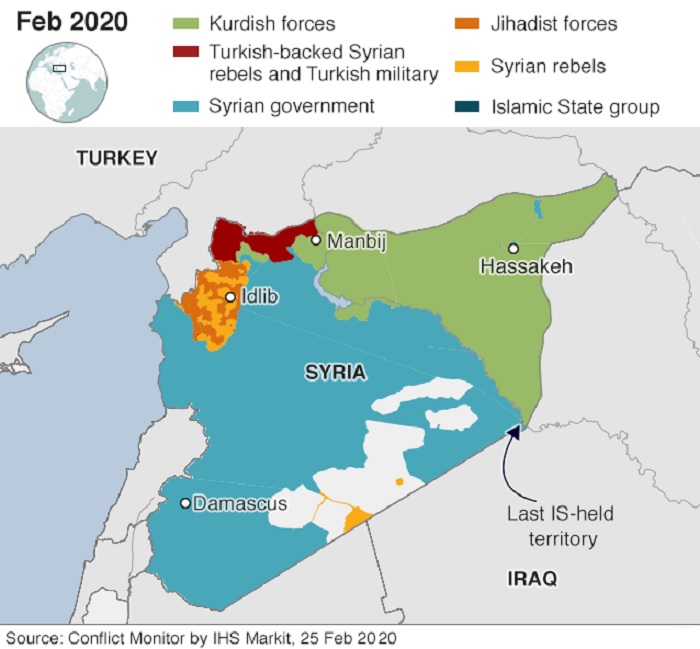

The government has regained control of Syria’s biggest cities. but large parts of the country are still held by opposition armed groups and the Kurdish-led SDF.

The last remaining opposition stronghold is in the north-western province of Idlib and adjoining parts of northern Hama and western Aleppo provinces. It is home to an estimated 2.9 million people, including a million children, many of them displaced and living in dire conditions in camps.

In September 2019, Russia and Turkey brokered a truce to avert an offensive by pro-government forces that the UN had warned would cause a “bloodbath”.

Rebels were required to pull their heavy weapons out of a demilitarised zone running along the frontline, and jihadists were told to withdraw from it altogether.

In January 2020, the truce deal was put in jeopardy when a jihadist group linked to al-Qaeda, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, expelled some rebel factions from Idlib and forced others to surrender and recognise a “civil administration” it backed.

The SDF currently controls almost all territory east of the River Euphrates.

The alliance had appeared to be in a strong position until December 2019, when President Donald Trump unexpectedly ordered US troops to start withdrawing from Syria with the territorial defeat of IS imminent.

The decision suddenly left the SDF exposed to the threat of an assault by Turkey, which has said it wants to create a “security zone” on the Syrian side of the border to prevent attacks by Kurdish fighters.

Kurdish leaders have urged the Syrian government and Russia to send forces to shield the border and begun talks about the future of their autonomous region.

Will the war ever end?

It does not look like it will anytime soon, but everyone agrees a political solution is required.

The UN Security Council has called for the implementation of the 2013 Geneva Communiqué, which envisages a transitional governing body “formed on the basis of mutual consent”.

But nine rounds of UN-mediated peace talks – known as the Geneva II process – since 2015 have shown little progress.

President Assad appears unwilling to negotiate with the opposition. The rebels still insist he must step down as part of any settlement.

Russia, Iran and Turkey have set up parallel political talks known as the Astana process. But they have also struggled to make headway.

In December 2019, the three countries failed to meet a deadline to form a committee to draft a new constitution after the UN said a list of participants they submitted was neither credible nor inclusive.