Abstract: Following its territorial loss of Sirte in December 2016, the Islamic State in Libya has rebounded to wage a war of attrition that seeks to derail Libyan state formation. During the last two years, the group has been able to ‘reset,’ moving through recovery, reorganization, and now re-engagement phases. The group is now waging two discrete campaigns: high-profile attacks on symbolic state institutions and a campaign in the southwestern desert—each of which constitutes a significant threat to any future progress in Libyan state-building. Despite its resurgence in Libya, the group may now face obstacles. As a result of the Libyan National Army’s (LNA) ongoing campaign to ‘liberate’ southern Libya from terrorists and to reopen its oil fields, the Islamic State in Libya may experience an erosion of its ability to operate in the Fezzan. Conversely, the LNA’s campaign may provide the group with an opportunity to exploit social fissures and perpetuate instability.

Over the course of the last two years, the Islamic State in Libya has gradually re-emerged as a formidable insurgent force. Following its territorial loss of Sirte in late 2016 to a U.S.-backed, anti-Islamic State coalition, the group has adopted new approaches to recruitment and financing. These reveal that the group has become more reliant on sub-Saharan African personnel in its post-territorial phase and has simultaneously deepened its connections with Libya’s desert smuggling networks, which connect North Africa to the Sahel. Moreover, as will be outlined in this article, its organizational structure appears to have shifted from ‘state-like’ to ‘guerrilla insurgency-like.’

All of these changes represent the Islamic State in Libya’s inherent opportunism and adaptability, characteristics that challenge the capacity and flexibility of Libya’s current security institutions. As will be outlined below, the Islamic State in Libya’s post-Sirte resilience was illustrated by it being able to mount three high-profile attacks on symbolic state institutions in 2018 and to progressively intensify its campaign in the desert that takes advantage of overstretched security actors. Taken together, these developments indicate that the group has again stepped up its efforts to derail state formation in Libya through a strategy of attrition (nikayah). As such, a resurgent Islamic State in Libya threatens the consolidation of any modicum of progress toward peace and prosperity in the country.

The underlying information for this article is derived from the data produced and cataloged by Eye on ISIS in Libya (EOIL), a data repository of Islamic State actions, attacks, and social media statements run by the authors and available publicly at www.EyeOnISIS.com.a

Part one of the article presents an overview of the Islamic State’s emergence in Libya in 2014 and how the group’s form and spatial localization have evolved due to the country’s post-Qadhafi political dynamics. In the wake of its territorial losses in 2016, the Islamic State in Libya has been pragmatic, with its proximal goal to prevent the consolidation of sovereign Libyan state structures.

In part two of the article, the authors identify two discrete, yet simultaneous, military campaigns that the group has undertaken in the wake of its eviction from Sirte in December 2016. On the one hand, the group has been launching high-profile attacks on symbolic state institutions along Libya’s coast. On the other hand, it has been carrying out a campaign in the desert across a larger area of the country than ever before.

These campaigns require money, manpower, and a suitable organizational structure, which is the focus of part three of the article. Previously, the group expended most of its resources in governing, terrorizing, and then losing Sirte.1 Therefore, to understand the enigma of the Islamic State’s resurrection in Libya, its new sources of funding and recruitment must be understood. The authors’ look at the Islamic State in Libya’s recruitment efforts and composition shows how the group has become progressively disassociated from its parent organization in the Levant and how its organizational chart apparently shifted from “state-like” structures to “guerrilla-like” ones as it wages a low-cost, high-impact war of attrition.

Part four of the article examines the future outlook for the Islamic State in Libya. Despite recent gains made by LNA forces in southern Libya which are threatening the Islamic State’s ability to operate in the Fezzan region, the Islamic State in Libya may actually pose a greater threat to Libyan state-building processes in 2019 than it did in 2016. During its peak of power in 2016, the group seems to have exerted a greater degree of governance over five percent of Libya’s territory than the country’s nominally sovereign Government of National Accord did over the remainder of the Libyan land mass.2 However, during that governance phase, the group was unable to undertake the sort of attacks that it has in 2018—namely three high-visibility-attacks on symbolic targets in Tripoli—combined with a series of delicate pinprick attacks that attempt to foil the nascent consolidation of security apparatuses in the south. As such, the Islamic State in Libya profoundly threatens Libya’s path to peace and prosperity. The international community would be remiss to continue pushing political reconciliation while not providing sufficient attention to the intertwined ‘elephants in the room’ of Libya’s illicit economy and the threat from a resurgent Islamic State satellite.

Part 1: The Rise and Fall of the Islamic State’s Territorial Control in Libya

Following the overthrow of Muammar Qaddafi in 2011, Libya’s transitional authorities were weaker than the non-state armed actors who monopolized local communities’ primary allegiances.3 After election results were disputed in 2014, Libya’s political and economic institutions were split along east-west lines.4 In response to these sudden fissures, the international community began a mediation process, which culminated in the December 17, 2015, Skhirat Agreement (also known as the Libyan Political Agreement). Since then, the Skhirat Agreement, which was meant to supersede the east-west division and reunify the country’s institutions, has paradoxically hardened Libya’s bifurcation into two zones. The Libyan National Army’s (LNA) coalition of anti-Islamist militias increasingly controls the east of the country, while the internationally recognized, U.N.-backed Government of National Accord (GNA) loosely holds sway in the northwest and acts as Libya’s nominally sovereign government on the international scene. Parallel to these political divisions, Libya’s important semi-sovereign institutions in the spheres of oil, banking, and sovereign wealth are also divided.5

Despite slow moves toward reconciliation, political and military alliances in Libya continue to prove fickle and are prone to abrupt change. Support and interference from external actors, in particular certain European, Arab, and African countries, have in many cases accentuated these divisions.6 As such, the ongoing political reunification process and the struggle among Libyan actors to ensure that their rivals do not come out on top has meant that the status quo (i.e., a state of perpetual disunity, a dysfunctional economy, and a fractured security sector) persists.

The Territorial Conquest and Subsequent Loss of Sirte

In the wake of Qaddafi’s death and particularly after the bifurcation of the country into two political spheres, the sovereignty and security vacuum deepened, providing an opportunity for the nascent Islamic State group in the Levant to transplant itself into Libya.7 The Islamic State in Libya’s first official branch was announced via the rebranding of existing Libyan al-Qa`ida-linked groups in the area of Derna in mid-2014.b This then attracted an influx of experienced foreign jihadis to assume leadership roles within the nascent organization.8

Islamic State Core leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi formally recognized the group’s presence in Libya in November 2014. Over the course of 2015, it established territorial control and governance mechanisms in parts of Derna, Benghazi, and Sabratha. It then launched a bold bid to conquer Sirte and threaten Libya’s Oil Crescent.9 By mid-2015, the Islamic State became the sole governing body in Sirte and at its peak may have had as many as 5,000 fighters occupying the city.10

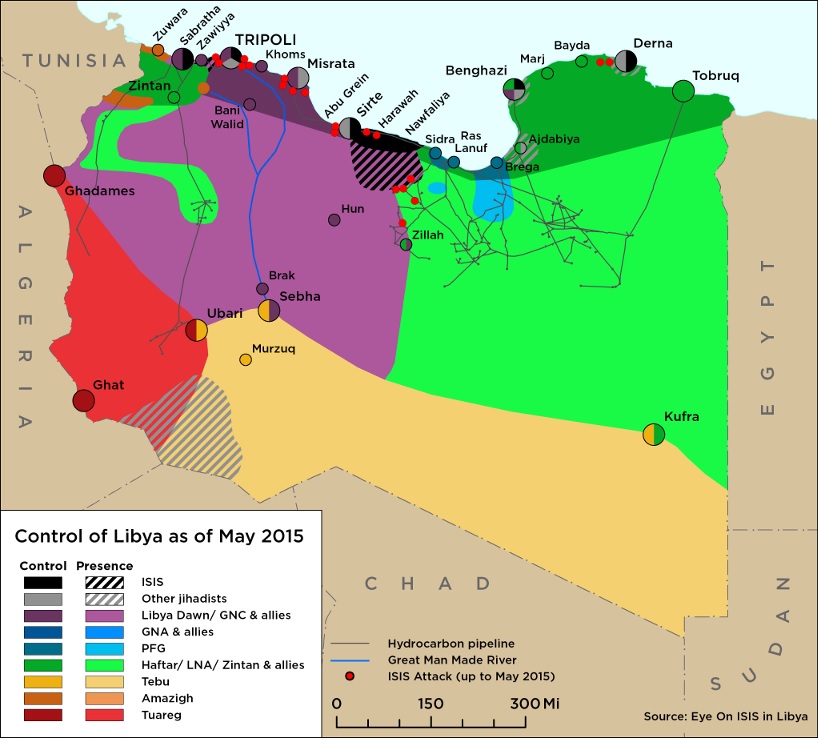

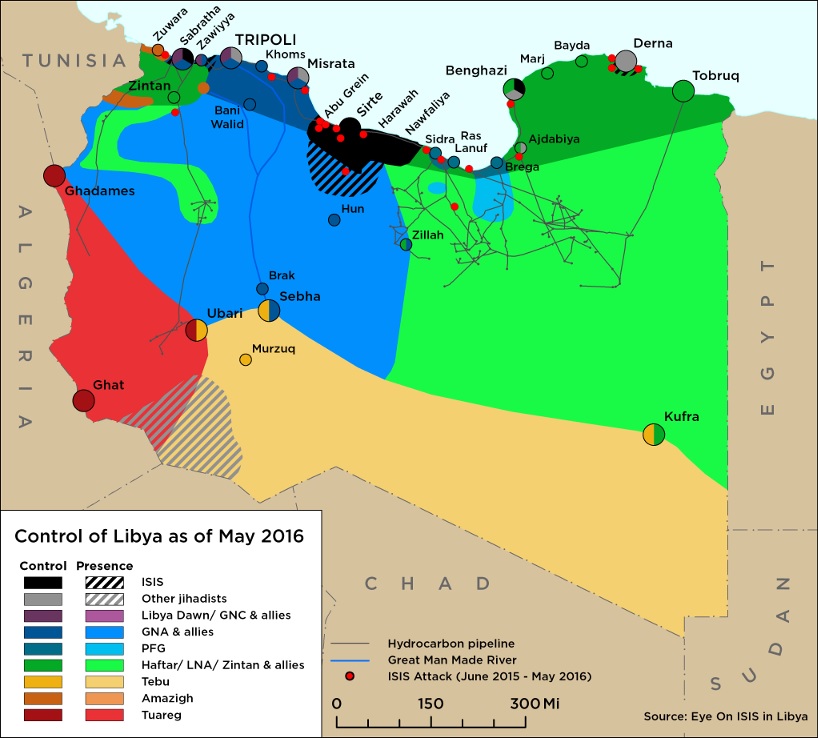

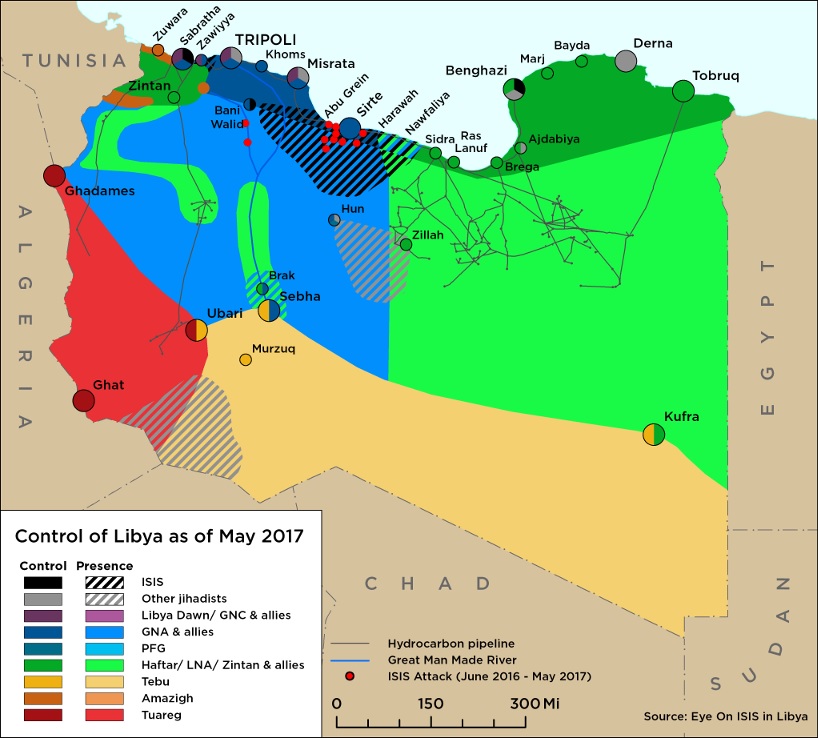

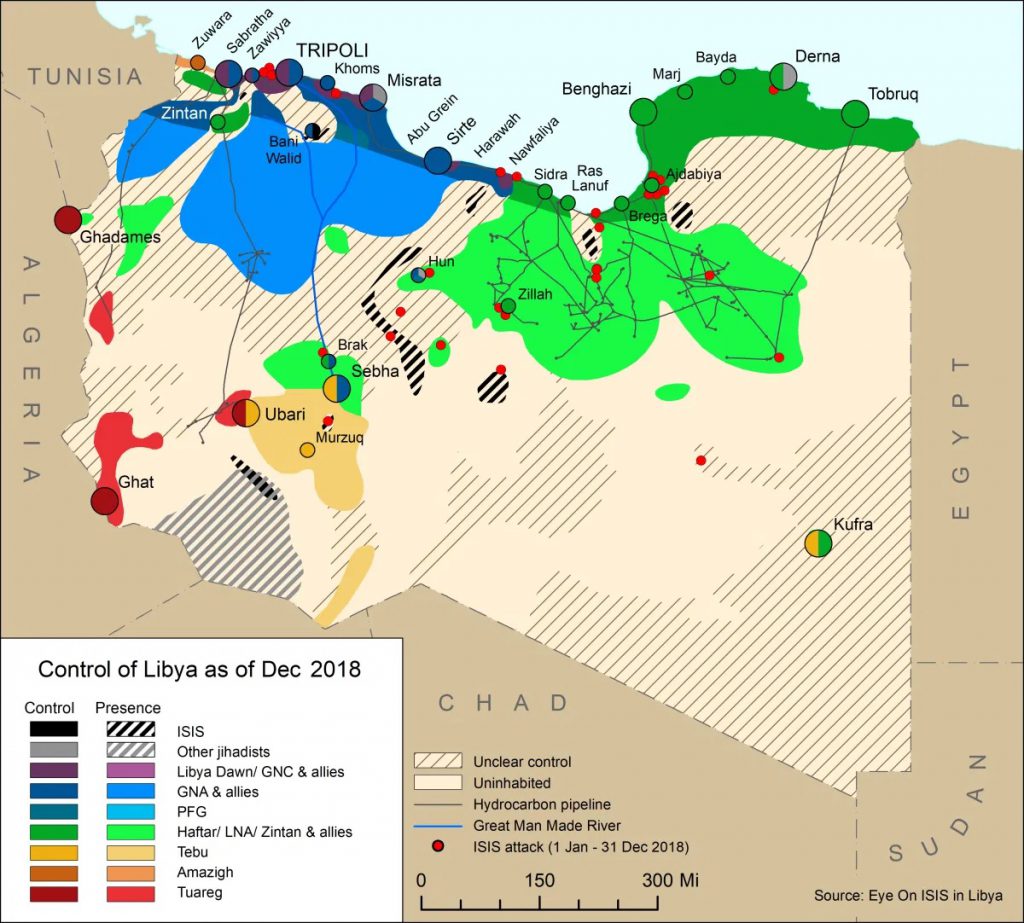

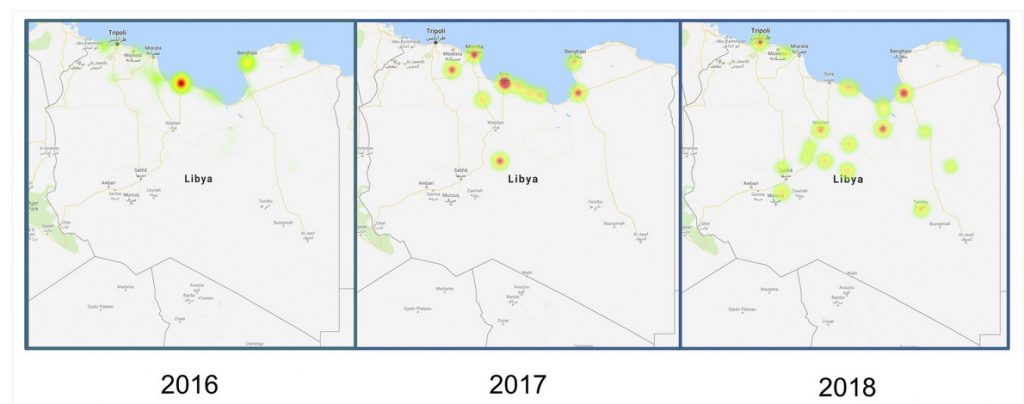

Throughout 2015, the increasing threat of further Islamic State expansion gave urgency to Western efforts to create a unified sovereign Libyan government, which could then legally grant permission for U.S. airstrikes in Libyan airspace.11 This process culminated in the aforementioned Skhirat Agreement in December 2015. After a very short grace period to consolidate his legitimacy, GNA Prime Minister Fayez al-Serraj authorized coalition airstrikes, which commenced on August 1, 2016.12 These—combined with prior local anti-Islamic State uprisings against the group’s brutality—virtually eliminated the group’s presence in Sabratha and Derna.13 Hence, by the end of August 2016, the group’s territoriality was concentrated in an ever-narrowing swath of coastal territory surrounding Sirte. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1: Maps showing control of Libya and Islamic State attacks as of May 2015, May 2016, May 2017, and December 2018.

The group’s territorial remit had been expanding from January to May 2016, but then after Islamic State forces encroached upon Abu Grein in May 2016 (i.e., precariously close to Misrata, the civic center of many of Libya’s most powerful militias), forces from the GNA-aligned, Misratan Bunyan al-Marsus coalition of militias advanced on Sirte and soon took over its outer suburbs. Bunyan al-Marsus had been lying dormant until this provocation; afterward, it took territory hastily until it met with resistance in pitched urban warfare battles in downtown Sirte. In August 2016, the United States began to provide it with air support, launching strikes on soft targets throughout the city.14 After more than 500 Bunyan al-Marsus combat deaths and much street-by-street fighting, especially around Sirte’s Ouagadougou center, on December 6, 2016, the Islamic State was declared to be “fully” defeated and expelled from Sirte.15

In the months that followed, the United States undertook a series of airstrikes throughout Libya,16 killing as many as 80 Islamic State fighters in one day in January 2017.17 At that time, knowledgeable sources estimated that the number of experienced Islamic State fighters in Libya had dwindled to some 200 fighters.18 Yet, follow-up to finish the group off was not decisive. Banyan al-Marsus forces were never able to coordinate with Zintani militia or Libyan National Army units tasked with fighting jihadis, and U.S. involvement in mopping up operations waned when the Trump administration came into office in January 2017.

Preparing for the Aftermath of Sirte

Prior to the coalition’s siege of Sirte in August 2016, the Islamic State claimed it had already begun conserving its forces for the eventuality of the loss of the city,c after which it planned to disperse into the desert and wage an insurgency.d The group’s emir in Benghazi, Abu Mus’ab al-Farouq, released a message claiming that the leader of its Wilayat Tarabuluse had fled and was already implementing a plan of recovery.19 This striking admission suggests that the Islamic State’s transition post-Sirte has been one of pragmatism, embracing the change of form forced upon it by territorial loss and new circumstances to continue to derail state formation in Libya by acting as a spoiler.f

Part 2: The Islamic State’s Post-2016 War of Attrition in Libya

In order to continue to play this spoiler role after the territorial loss of Sirte, the Islamic State appears to have shifted strategy. Since the start of 2017, the Islamic State in Libya has been undertaking a strategy of nikayah, or a ‘war of attrition,’ as its new military principle—even going so far as to explicitly state this in 2018.20 This mirrors both rhetorical and strategic developments in the Levant after the Islamic State lost its territoriality there.21 In 2018-2019, the Islamic State in Libya’s actions and statements indicate that, for the time being, it no longer aims to win or hold territory. Rather, it appears to have deliberately returned to the Islamic State’s first phase of insurgent activity, termed “Vex and Exhaust” by the jihadi theorist Abu Bakr Naji.22

The Islamic State emerged in both the Levant and in Libya in the wake of protracted civil wars and concomitant state collapse. This apparent “Vex and Exhaust,” or attrition, strategy aims to further weaken ‘the enemy’ (the Arab nation-state)—with which the Islamic State competes for resources, manpower, and dominance—as well as to prevent the post-Arab Spring re-establishment of state security apparatuses and sufficient social cohesion that could restore political order and “challenge the presence of the jihadis.”23 Post-2016, the Islamic State in Libya appears to be implementing this strategy of attrition through two mutually reinforcing campaigns: high-profile attacks on symbolic state institutions and a guerilla campaign in the desert.24

High-Profile Attacks on Symbolic State Institutions

The more visible of the Islamic State in Libya’s two simultaneous campaigns involves sleeper cells undertaking spectacular, but infrequent, attacks targeting institutions that symbolize and administer the three key issues facing Libya post-Qaddafi: political reunification, foreign engagement, and economic reform. Within the last 12 months alone, the Islamic State in Libya has undertaken three such attacks, all of which targeted Tripoli and involved a suicide bomber or bombers. The attacks targeted the Libyan Foreign Ministry, the National Oil Corporation (NOC), and the High National Electoral Commission (HNEC).25 By attacking these institutions, the Islamic State appears to be attempting to unsettle foreign assistance, weaken Libya’s recovering oil sector (on which the whole economy depends), and disrupt elections.

These attacks are directly in line with the group’s articulation of the Islamic State Core’s global strategic objectives to break or prevent the reconstitution of regional states and remove Western presence.26 The media arm of the Islamic State Core’s central command, Nashir, claimed responsibility only hours after the attack on HNEC on May 2, 2018, identifying the assailants and stating that the attack was in response to its spokesman’s call to “attack the apostate electoral centers and those calling for [the election].”27 Likewise, in the group’s claim of responsibility for the NOC attack on September 10, 2018, the Islamic State in Libya referred to its activities as a “continuation of the attacks against the economic interests of Libya’s tyrant governments that are allied with the crusaders.”28 Furthermore, the attacks on the GNA and institutions aligned with it (i.e., the NOC, HNEC, and the Foreign Ministry on December 25, 2018) are not only a physical and conceptual assault on the principle of state sovereignty and governance, but also a symbolic attack on the role of the international community in Libya.

All of the Islamic State’s high-profile attacks on symbolic state institutions in 2018 focused on the GNA rather than Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar’s LNA. This may seem surprising given Haftar’s strident anti-jihadi stance. But the group may be making a strategic calculation assessing that the U.N.- and Western-backed GNA is the most likely source of successful state building.

All three of the Islamic State’s high-profile 2018 attacks in Tripoli appear to have been coordinated through a network of cells linked to southern Libya. In January 2019, the Tripoli-based Special Deterrence Force (Rada) made a call for public information on two Islamic State members based in Sebha, in southwestern Libya, due to their suspected participation in and coordination of the attacks on Tripoli’s HNEC, NOC, and the Foreign Ministry.29 Likewise, at the start of 2018, Rada arrested two would-be Islamic State bombers in Tripoli who had arrived from the desert areas near Sebha.30 Despite the distance of over 750 kilometers, this suggests that access to Libya’s south is important to operations in the capital. This linkage in the jihadi sphere mirrors similar south-north connections in the spheres of oil, migrants, water, and electricity, and demonstrates that Libya’s political problems cannot be fixed solely by securing a détente among coastal actors. The Islamic State’s ability to undertake coastal operations depends upon its maintenance of a supply network that transverses the Sahara.

The Campaign in the Desert

The Islamic State’s terrorist campaign against symbolic state institutions has, in the last year, been supplemented by a rural and desert-based jihadi guerilla insurgency in the interior parts of the Oil Crescent and in southwestern Libya (Fezzan). As Figure 2 shows, the Islamic State in Libya’s attacks show a greater geographic dispersal across the country over time, indicating the group has significantly increased its capacity to geographically spread attacks across the Libyan deserts.g The Islamic State in Libya’s ‘southern strategy’ provides it not only with a base to plot attacks, train operatives, and gain resources, but its attacks on local security forces in the desert, primarily the LNA, allows it to simultaneously disrupt attempts of coastal actors to foster governance in the south.h

In its campaign in the desert, the Islamic State in Libya undertakes hit-and-run attacks in formations ranging in size from half a dozen to two dozen fighters.i The attacks themselves, the use of sanctuaries, and the relationships to various local community hosts follow a similar approach to the classic theories of Mao Tse-tung on the stages of guerilla/revolutionary warfare, in which insurgent groups can use their attacks to harm the enemy, increase their recruitment, cement their local alliances, and build their internal organization, all simultaneously.31

Footage released by the Islamic State in Libya’s 2018 “The Point of Death” video, along with GoPro footage captured following an assault on al-Qanan police station, illustrates its ‘Campaign in the Desert’ in action.32 Like any well-executed guerilla campaign, it is well adapted to take on an overstretched military actor operating in a vast, inhospitable territory occupied by an ambivalent or hostile populace. Indeed, these tactics are currently being employed against the LNA to stretch its limited resources and troops across the Oil Crescent and Sirte Basin. For example, the Islamic State in Libya—as well as other Libyan militant groups such as those under the command of Ibrahim Jadhranj—capitalized on the LNA’s inability to simultaneously coordinate its forces during its campaign in Derna and protect the far-flung Oil Crescent. As a result, most of Libya’s key oil installations have proven remarkably vulnerable to hit-and-run attacks, despite the LNA increasing its fortifications.33

It is worth noting that the Islamic State’s increasing activity in southern Libya has not been defined exclusively by opportunism.34 Rather, its movement away from operations in the Sirte Basin was due also to a lack of support from the local population in response to the crimes and brutality it committed in 2015 and the loss of its economic extraction networks.35 Furthermore, the Islamic State in Libya faced initial trouble inserting itself into the Fezzan, due to having limited connections in the area. It resorted to buying its way into the region by sending out envoys to the towns of Zwelia, Temess, and Ubari with piles of cash to establish relationships with local groups.36

A Resurgent Group

The Islamic State may never be able to concentrate power as it could when it controlled Sirte, but its geographic scope of operations is now broader, having dispersed across the country to occupy the interstices in Libya’s post-Qaddafi security order.37

Moreover, the international community’s mediation process in Libya’s civil war has reached a crucial moment.38 The U.N. Envoy Ghassan Salamé’s frequently delayed three-step plan is supposed to culminate in a national conference and elections, and the Islamic State’s leadership in Libya most likely understands the symbolic and practical threat posed by progress in either of these two areas. Failure for the U.N. to bring about elections in 2019, could result in the termination of the state building project as previously conceived and pursued by international actors since the Skhirat Agreement.

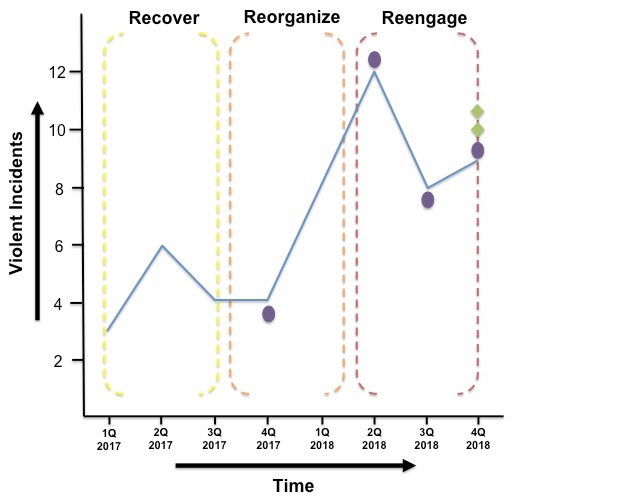

Figure 3 shows that the Islamic State in Libya over the course of 2018 has re-engaged in the Libya crisis, after a 15-plus-month lull from December 2016 to early 2018 during which the group had a smaller impact. The rate at which the group is undertaking spectacular attacks on the coast, as well as the targeting, and coordination, of hit-and-run attacks on desert towns, increased significantly in the third quarter of 2018. (See Figure 3.) Quantitatively and qualitatively, this trend is indicative of the group’s re-emergence as a force capable of altering nationwide dynamics. What this also indicates is a renewed enthusiasm and confidence by the group, which now appears to exhibit a higher tolerance of risk (given the rise in attack tempo despite its fewer members post-Sirte) and willingness to sacrifice precious manpower and resources to achieve its goals of derailing state formation and political progress.

Equally, the Islamic State in Libya has demonstrated the on-the-ground intelligence needed to allow its members to carry out complex operations. Its operatives display situational awareness of how their cells in cities are monitored via surveillance and informants.k These were areas of weakness for the group in 2014-2016 when it upset local communities with its brutalism and crudeness, highlighting its lack of cultural sensitivity and local knowledge.39

Part 3: Delivering a High-Impact War of Attrition at Low Cost

The Islamic State in Libya’s dual campaigns apply different tactics, yet they share a common feature. Both are executable by limited numbers of fighters, while still delivering high-impact results. By adapting its structure and employing low-cost hit-and-run (in the desert) and spectacular attacks (on the coast), the Islamic State in Libya has been able to maintain its presence in Libya and weaken its enemies—despite its limited, self-funded revenue and loss of its former riches.

Funding

Though it is no longer in possession of its tens of millions of dollars acquired from bank robbery nor able to finance its prior budget of millions of dollars a month in salaries40 through the taxation of the territories it controlled during 2015-2016, the Islamic State in Libya continues to extort civilians through temporary checkpoints,41 kidnapping for ransom,l raids on local security outposts, and undertaking smuggling-related activities.42 The group likely retains a minority part of the monies accumulated in Sirte and processed by its Dar al-Muhasaba (accounting department), though the exact amount remains unknown. The organization also continues to participate in migrant and other smuggling rackets.43 Its movement toward southern Libya has helped facilitate an expansion into the realm of migrant smuggling to compensate for losses in its taxation capabilities.44

The Reliance on Foreign Fighters

By employing military tactics that only require small units, the Islamic State in Libya post-Sirte has been able to maximize its impact despite limited membership. At the conclusion of 2018, according to AFRICOM, the Islamic State had as many as 750 members in Libya.45 m There has not been a noticeable influx, as once was feared, of seasoned jihadis fleeing the Levant after the fall of Mosul and Raqqa.46 In fact, over the past two years, the Islamic State in Libya appears to have become more disconnected, from both a personnel and a command-and-control perspective, from Islamic State Core.n In part, this may be due to the depletion—through either death or arrest—of senior leaders in the group with established ties to the Levant, such as Abdelhakim al-Mashout who had previously fought with the Islamic State in Syria before returning to Libya.47

It is difficult to ascertain the membership profile of any clandestine group, but according to “AFRICOM sources” cited in an article recently published by The Jamestown Foundation, non-Libyans make up almost 80 percent of the Islamic State in Libya’s current membership.48 This is consistent with what the authors have deduced from their Eye on ISIS dataset. Whatever the precise numbers, it seems clear that the group has an extremely high proportion of foreign fighters.49 Yet, the Levantine nationalities that dominate the Islamic State Core’s leadership are underrepresented in the Islamic State in Libya. According to data released by Libya’s Attorney General in 2016, at the group’s peak, the majority of foreign fighters were from Tunisia, Egypt, and Sudan, with notable representation from Chad, Niger, Senegal, Gambia, Ghana, Eritrea, and Mali.50 Individuals from Saudi Arabia, Palestine, Morocco, Mauritania, Yemen, and Algeria were also in the group’s ranks, though they were speculated to have been in much lower numbers.51 Syrians and Iraqis are essentially absent from the Islamic State in Libya post-Sirte, suggesting one of three possible scenarios: one, that those fighters appear wedded to the ongoing struggle in their homelands; two, that they have not been interested in seeking sanctuary in Libya’s less governed spaces; or three, that clandestine travel from the Levant to Libya has been difficult to achieve or deemed dangerous.o

Current Tunisian membership figures in the Islamic State in Libya remain unclear, but it is believed they once constituted around 50 percent of the group’s membership.52 In addition to dominating the commander rungs of the Islamic State in Libya, Tunisian jihadis had their own separate base in Sabratha, 78 kilometers west of Tripoli and a mere 102 kilometers east from the Tunisia border.53 Sabratha functioned something like an extraterritorial sanctuary beyond the reach of Tunisian authorities, allowing them to wage jihad in Libya while also preparing for attacks back home.54 Sabratha was the command-and-control nexus for Tunisian jihadis with its own direct channels to Islamic State Core for communication and command-and-control. It served as an external operations hub for the Islamic State in Tunisia and was central in mobilizing Tunisian fighters to Sirte and Benghazi.55 The Tunisian Sabratha wing of the Islamic State was effectively dislodged from the city following U.S. airstrikes on the base in February 2016 and a crackdown by locals on the armed groups in their midst.56 Importantly, certain critical figures—such as Abdelhakim al-Mashout—involved in bringing Tunisians through the western border have been either killed or arrested.57 However, Tunisian foreign fighters are still attempting, at the time of publication in March 2019, to enter Libya through the western border, and it remains a possibility for the Sabratha network to be re-established.58

Since the fall of Sirte, sub-Saharan Africans have had a progressively stronger presence in the Islamic State in Libya with the group taking advantage of its links to human trafficking networks to recruit from among migrants attempting to reach Europe.59 According to a Libyan official dealing with illegal immigration interviewed by Libya expert and journalist Tom Westcott in the summer of 2018, the group’s southern ranks are composed of both those who fled Sirte and “new migrant recruits.” The same official described the group’s desert forces as a blend of Libyans and foreigners, predominantly sub-Saharan Africans.60 p Given these developments, it should no longer be a surprise that sub-Saharan Africans are currently represented more than any other ethnic groups in the Islamic State in Libya’s propaganda videos, likely in an effort to continue to draw recruits.61

The fact that many, if not most, of the Islamic State’s fighters in Libya are non-Libyan likely reflects its struggle to recruit locally and has reinforced the perception that the group is in, but not of, Libya. Libya’s intense localism has been attributed as one of the key limiting factors on the Islamic State in Libya’s ability to recruit Libyans, who given the fractured internecine struggles in their homeland generally fail to identify with the group’s global narrative.62 However, in certain instances, the Islamic State in Libya previously took advantage of local grievances due to feelings of economic marginalization in places like Derna and Benghazi and political marginalization elsewhere.63 By modifying its rhetoric in those areas, the group was able to find tentative support among Qaddafi loyalists in Sirte and Bani Walid who felt excluded from the post-Qaddafi political process.64 Capitalizing on the marginalization of young Libyans for recruitment is no longer a significant factor in coastal Libya, which has dramatically turned against the Islamic State and most jihadi groups.65 Conversely, the economically and politically disenfranchised south, where the group is now embedding itself, may provide a pool from which it can draw recruits, albeit as part of a crowded recruitment marketplace where the Islamic State has to contend with other armed groups and established jihadi organizations such as al-Qa`ida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM).66

In sum, despite rebounding from their nadir of possibly as low as 200 fighters,67 the Islamic State in Libya’s membership numbers have not returned anywhere near their Sirte governance levels, due in part to limited local Libyan recruitment and the absence of a burgeoning foreign fighter contingent (except among sub-Saharan Africans). Nonetheless, the group’s current strategy and tactics in Libya have succeeded in turning these limited numbers into an asset—and as will be outlined below—its leadership has restructured accordingly.

Structure

The Islamic State in Libya’s organizational structure appears to have changed from three separate wilayat (provinces demarcated along the supposedly traditional Ottoman/Italian/monarchial provincial boundaries) with defined state-like departments (diwans) and a hierarchal chain of command, into guerilla-style desert brigades and networked cells with more horizontal command structures.68 q The small size of these cells makes their detection more difficult, allowing the group to better achieve the hit-and-run tactics needed for its ‘Campaign in the Desert.’r It is crucial to remember that when the Islamic State was seeking to expand its territorial reach and financial catchment area outward from Sirte in 2015-2016, it very infrequently dispatched cells for hit-and-run attacks far away from its base of operations. As shown in Figure 3, since 2017, the group has demonstrated new capacities to launch hit-and-run attacks in Libya’s vast deserts, even as it has shrunk in size.

In effect, the Islamic State in Libya has undergone a transition backwards from Stage III to Stage II of Mao Tse-tung’s classic trajectory of revolutionary warfare organizations.s In effect, the Islamic State in Libya has reverted to disparate insurgent cells.69

Although it is impossible to know the actual organizational structure of the group at present, the authors’ data indicates that the Islamic State in Libya is now focused around a few prominent commanders.t After the loss of Sirte in 2016 and the sustained U.S. airstrike campaign in 2017 targeting key Islamic State camps and hideouts near Sirte, Bani Walid, and Sabratha, the group’s top- and mid-tier leadership were significantly weakened.70 Despite this, the group managed to preserve a modicum of its initial rank-and-file manpower post-Sirte, and now several notable top-tier leaders have emerged to facilitate its new strategy.

This leadership cadre has included Mahmoud al-Barassi (a Libyan national from a prominent eastern tribe) and Al-Mahdi Rajab Danqou. Al-Barassi, who founded the group’s Benghazi branch and led the bombing and assassination operations against local security forces, is thought to have led the group’s remnants operating in the desert areas between Ajdabiya and Bani Walid.71 Paradoxically, he is also suspected of being killed in the clashes around Wadi al-Jaf along with the rest of the assailants responsible for the attack on Al-Uqaylah in late July 2018.72 In contrast, Al-Mahdi Rajab Danqou (aka Al-Mahdi Salem Dangou, aka Abu Barakat), who headed the “Soldiers and Military Diwan” (i.e., the Islamic State in Libya’s former Ministry of Defense), is thought to be aliveu and believed to lead the group’s ‘Desert Brigades.’73

Part 4: Future Outlook

Ultimately, the Islamic State’s presence in Libya is a symptom of the country’s instability; the root cause is state implosion and the perverse incentive structures of a dysfunctional economy—one in which the GNA’s budget subsidizes easy-to-smuggle goods, such as fuel (that can be sold at a higher profit over the porous border, for example in Tunisia), and the central bank pays most militia members a government salary.74 Under these prevailing conditions, the Islamic State in Libya and other jihadi actors appear poised to continue their current trajectory of gradually rebuilding their capabilities to impede U.N. mediation efforts and domestic state-building. The ongoing Libyan political crisis has provided a security vacuum in which the Islamic State and other non-state actors can freely operate, as well as opportunities to recruit from the politically and economically disenfranchised, to profit from the migrant crisis, and to establish connections to transnational crime and trafficking networks. As a result, over the last two years, the Islamic State in Libya has re-emerged after its territorial defeat: progressively rebuilding its capabilities, restructuring its organization, and regaining its confidence to wage a war of attrition against Libyan national unification, political stability, and economic growth.75

However, there could be obstacles ahead for the group. As a result of the Libyan National Army’s (LNA) ongoing campaign to ‘liberate’ southern Libya from terrorists and to reopen its oil fields, the Islamic State in Libya may see an erosion in its ability to operate in Libya’s Fezzan.

In the first two months of 2019, the LNA took control of Sebha, Murzuq, and Ghat and is moving to control Qatrun and Wigh Airfield—allowing it to be the first force since the fall of the Qadhafi regime to effectively extend its control into the Fezzan. This territorial expansion has brought all of Libya’s major onshore oil fields under the LNA’s aegis.76

The LNA looks set to push into the Harouj Mountain region, where it had previously pursued the Islamic State following the group’s attack on Tazirbu on November 23, 2018, and where the latter is known to have found sanctuary.77 Taken together, the LNA’s significant progress in the Fezzan in early 2019 presents the most significant threat to the Islamic State’s re-emergence since the group was evicted from Sirte more than 26 months ago and has progressively elected to base its supply and sanctuary networks in the Fezzan.78

If the LNA is able to effectively link its nascent security structures in key southern locations to operational and intelligence hubs in coastal Libya and to use this new network to undertake coordinated counterterror actions, then the Islamic State in Libya may be forced into another period of decline. Although the group has gained momentum, recruits, and money over the past year, it is still incapable of standing up to coherent and consolidated security forces able to effectively share information and undertake active pursuit against it. Indeed, according to several theorists of asymmetrical warfare, insurgent actors cannot regain ground and then simply stand still. They either continue to gain momentum and grow, or if their power is decisively checked they wither and die.79

Conversely, if a new round of tribal and ethnic fighting erupts in the Fezzan as a result of the disruption of the social and power dynamics due to the LNA’s campaign or the inability of the GNA and LNA to work together, the Islamic State has amply demonstrated that it is able to recruit and amass financial resources amid instability. At present, the authors do not see the worst-case scenario of prolonged chaos and an Islamic State victory in the Fezzan as inevitable. Even though the LNA has been gaining momentum and expanding its network of alliances, a jihadi counterstrike or a collapse of coastal power centers could still materialize. Even amidst the LNA’s encroachment on its sanctuary and supply chains, clear and credible threats of an attack by the Islamic State in Tripoli persist.80 This ability to simultaneously operate in multiple theaters, even under duress, is indicative of the group’s staying power and adaptability. Additionally, loose regional territorial control by its opponents is unlikely to be enough to disrupt the group’s geographically dispersed, but coordinated operations. Given the resurgence of the Islamic State in Libya, as catalogued in this article, the security situation could be improved if Libyan authorities and their international allies were able to coordinate the security apparatuses in the south with those in coastal Libya, as well as undertake long overdue economic and structural reforms so as to close the loopholes through which the group and other destabilizing armed actors finance themselves.

Looking further ahead over the next year—and assuming that sufficiently bold and coordinated actions from Libyan authorities and their international partners fail to materialize—the status quo in Libya will most probably be maintained: an inconclusive national conference may or may not take place; national elections are likely to be further pushed back; and if/when elections are held, they are not likely to produce a truly unified or sovereign governance body.81 Indeed, a push to have premature elections may even lead to a full-scale civil war.82 In this and other similar scenarios, the Islamic State in Libya is poised to exploit latent social fissures to help facilitate a descent into a large-scale conflict. In doing so, the group will be fulfilling its proximal ambition: maintaining the vicious circle of instability in Libya, which provides it with an ideal breeding ground.