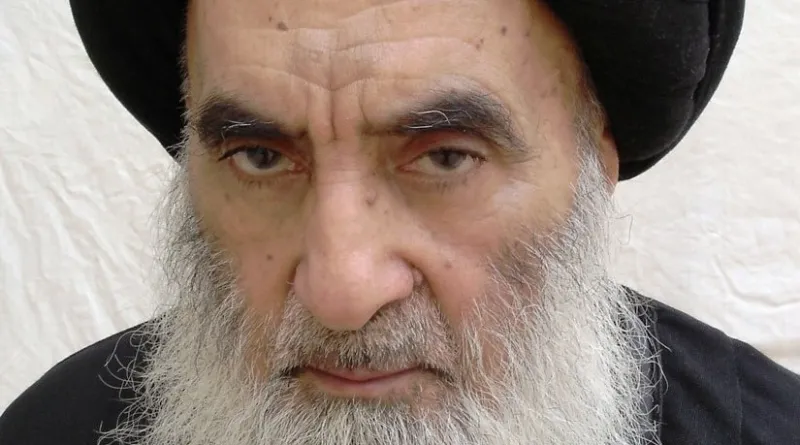

Besides Pope Francis and the Dalai Lama, few religious leaders today command as much respect among Muslims and non-Muslims alike as Grand Ayatollah Ali Al-Sistani, the 91-year-old “supreme marja” of the world’s Shiite Muslims.

Al-Sistani was a disciple of Ayatollah Abu Al-Qasim Al-Khoei, who was for decades the most renowned religious teacher in Iraq’s shrine city of Najaf, where he was known as the “professor of jurisprudence.”

His lectures were attended by hundreds of students, many of whom would themselves become leading Shiite jurists in Iraq, Iran, Lebanon, Pakistan and the Gulf.

After Al-Khoei died in 1992, a number of religious scholars in Najaf emerged as leading muftis. Among the most influential were Sayyid Abd Al-Ala Al-Sabziwari, Sheikh Ali Al-Gharawi, and Sayyid Ali Al-Sistani.

There was also a group of jurists in the seminary in Qom, Iran, among whom were Sayyid Mohammed-Reza Golpaygani, Sheikh Mohammed Ali Al-Araki, Sayyid Mohammed Al-Ruhani and Sheikh Mirza Jawad Al-Tabrizi.

After the deaths of several of these leading muftis, Al-Sistani was named marja — meaning literally “source to follow” or “religious reference” — granting him the authority to make legal decisions within the confines of Islamic law.

This was despite the presence of popular figures in Iran such as the “revolution’s guide” Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and Sheikh Nasser Makarem Shirazi, and others in Iraq such as Sayyid Mohammed Saeed Al-Hakim and Sheikh Ishaq Al-Fayadh.

Al-Sistani soon emerged as a popular and trusted religious guide, but after the fall of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein in 2003 his name grew in prominence beyond the boundaries of the seminary and even beyond the borders of Iraq.

Such was his influence that international delegations would routinely visit him at his humble home in Najaf. Iraqi politicians also flocked to meet Al-Sistani to win his support. But as he became increasingly disappointed by the spread of corruption and sectarianism in Iraq, he stopped giving these audiences.

Now, given Al-Sistani’s advanced age, the question of who will succeed him has become increasingly urgent.

During the past two decades, there have been four great jurists in Najaf: Al-Sistani, Mohammed Saeed Al-Hakim, Bashir Al-Najafi and Ishaq Al-Fayadh. Al-Hakim was viewed by many as the likely successor but he died on Sept. 3 this year, casting the succession into doubt.

Sheikh Hussein Ali Al-Mustafa, a Saudi researcher who specializes in Islamic sciences, said Al-Sistani’s inevitable passing will come as a blow but one that the community will absorb and eventually overcome.

“The post-Sistani era will face any issues and the Najaf seminary is capable of filling the void, even though Al-Sistani’s absence will constitute a great loss not only for Shiite Muslims, but for all believers in moderation, tolerance and coexistence,” he told Arab News.

“There are basic constants in the Najaf jurisprudence school and these constants will not change, whether Al-Sistani is dead or alive. These constants are: Avoidance of direct political action; no truck with political parties; focus on people’s interests and easing their suffering through social and economic services; and satisfactory answers to believers’ jurisprudential questions.”

But why is the fate of the Najaf seminary considered so important?

“Najaf has five important characteristics,” Jawad Al-Khoei, secretary-general of the Al-Khoei Institute in Najaf, told Arab News. “It is the oldest scholarly estate of Shiite Muslims that has survived to this day, as it is more than a thousand years old, in addition to the fact that it includes the resting place of Imam Ali bin Abi Talib.

“It is also known for being financially independent for decades, which has made it relatively free to issue fatwas; its refusal to mix religion with politics; its rejection of calls for the establishment of an Islamic government; and for the research and scientific freedom it enjoys.”

He added: “All of this has given Najaf a role that transcends its religious duties, to be a sponsor of people’s interests, working to repel harm away from the people and seeking to solve their social, life and cultural problems, with the marja’s main concern being people.”

Al-Sistani’s authority has gone far beyond the traditional role of the marja, including a hand in trying to heal the rift between Sunni and Shiite Muslims. In 2007, he said he is “at the service of all Iraqis,” stressing that there are no “real differences between Sunnis and Shiites.”

In one speech, delivered by his representative, he said: “Shiites must defend the social and political rights of Sunnis before Sunnis themselves do it, and Sunnis should do the same.”

Al-Sistani’s patriotic stand has made him a guardian of sorts for all Iraqis. His bona fides were burnished in Najaf in March this year by the meeting between him and Pope Francis, the head of the Roman Catholic Church, during which they discussed ways to promote peace and coexistence.

Clearly, Al-Sistani’s outsized persona will loom large over his successor, who is likely to be someone deeply influenced by his ideas and who has worked as part of his team. But the question remains as to which of them will attempt to fill his shoes.

“Usually, a jurist does not immediately become a marja after being commissioned to the position of marja. This rather happens through different stages and over several years,” said Al-Khoei.

“Either other jurists of equal rank pass away, or they are nominated by experts in the seminary and the most important professors who conduct accurate specialized research into their level of expertise and disciple count, without forgetting the number of testimonies of ijtihad they received from senior jurists who preceded them.

“Then there are the jurist’s books, the level of their depth and scientific accuracy, plus another important element, which is piety.”

There are currently more than 40 religious scholars who offer “external research” courses at the Najaf seminary. These highly specialized jurisprudence and religious sciences studies are equivalent to a doctorate in regular universities. Those who pass this stage receive a degree of “ijtihad,” though its levels vary from one scholar to another.

The jurists most likely to emerge during the “post-Sistani” era can be divided into three main categories, based on the hierarchy of age, education and experience.

The first category includes older jurists of high educational rank who are loyal to Al-Sistani. These include Al-Fayadh and Al-Najafi.

However, their advanced ages and classical style will make them less attractive to the new generation of Shiites, who want the marja to be younger, more modern in outlook and better able to understand the rapidly changing times.

Al-Fayadh and Al-Najafi are now maraji taqlid — or a “source of emulation.” If their status remains unchanged, it is possible that a small number of Al-Sistani’s “emulators,” especially Shiites in Afghanistan and Pakistan, might consider him their reference after his death.

The second category includes highly educated jurists such as Sheikh Baqir Al-Irwani, Sheikh Hadi Al-Radi, Sheikh Hassan Al-Jawahiri, Sayyid Mohammed Baqir Al-Hakim, and Sayyid Mohammed Jaafar Al-Hakim.

Given the advanced age of the Al-Hakim brothers, their ascetic way of life, their eschewing of political matters and their refusal to address fatwas, it is unlikely that they will be considered for the position of marja after Al-Sistani.

Al-Radi, Al-Irwani and Al-Jawahri have a large circle of students and are greatly respected within the seminary.

“These three names have the biggest advantage in the post-Sistani stage, because of their jurisprudential depth and ability to research,” said Islamic scientist Al-Mustafa.

“They have experience and exposure, therefore the wider audience of Al-Sistani’s followers will — most likely — refer to them, whether in Iraq, the Arab Gulf or Europe.”

The third category includes scholars such as Sayyid Mohammed Ridha Al-Sistani, Sayyid Mohammed Baqir Al-Sistani, Sayyid Riyadh Al-Hakim, Sayyid Ali Al-Sabziwari, and Sayyid Sadiq Al-Khorsan. They too enjoy “ijtihad” and have students spread throughout international seminaries.

However, sources close to the Najaf seminary told Arab News that the Al-Sistani brothers will not take up the position of marja after the death of their father because “traditions in the seminary forbid the inheritance of the marja position from father to son.”

In addition, “despite the proven knowledge of Sayyid Mohammed Ridha Al-Sistani, he has no personal desire to be a marja. He is happy with teaching and participating in managing the affairs of his father’s religious reference.”

Ayatollah Riyadh Al-Hakim, who is seen as a modernizer, is the son of the late Sayyid Mohammed Saeed Al-Hakim. He resides in both Iran and Iraq and “has very good administrative experience as well as the ability to understand political, social and cultural developments,” a source close to Al-Hakim’s family told Arab News.

All indications from Najaf are that Mohammed Baqir Al-Irwani, Sheikh Hassan Al-Jawahiri and Sheikh Hadi Al-Radi are the three most likely candidates to assume Al-Sistani’s mantle.

But so glacial is the “supreme marja” selection process that Al-Sistani’s successor most likely will not be known any time soon — or even immediately after his era has ended.