When it was signed four years ago, the Iran nuclear deal was widely perceived as a diplomatic triumph, a move that would help reintegrate Iran into the global economy and restore its relations with the West. Things haven’t quite turned out that way, however.

Even before President Donald Trump decided to withdraw from the deal in May 2018, the outcome Iran had hoped for — a revitalized economy and a modernized energy sector — hadn’t materialized. In fact, Iran failed to significantly increase its oil output, upgrade its energy infrastructure, or jump-start its economy. There were a variety of reasons for this, including the impact of American limits on access to financial markets, the short timeframe for addressing long-standing structural economic issues, low oil prices, and the change in U.S. administration. President Trump’s May 2018 decision put an end to Iran’s plans, crushing its efforts to revive its energy sector, regain its political standing, and rejoin the global economy.

Many have argued that Russia and other major energy exporters like Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Iraq have been the primary beneficiaries of the renewed U.S. sanctions on Iran. While this is true to an extent, in the case of Russia it has not been a decisive factor in shaping the country’s energy policies because, in reality, Iran was never a serious threat to its energy interests in the first place.

Lessons from the past

The current situation is reminiscent of 2011-12, when Iran was hit hard by sanctions aimed at curbing its nuclear program. Its oil output and exports suffered significant losses as a result, with production dropping by 17 percent while exports fell by about 60 percent. This led to a reduction in Iran’s market share, for which other oil exporters quickly compensated. However, even after sanctions were eased in 2016, Iran was not able to completely regain its lost market share or compete meaningfully with Russia.

In the two years after most sanctions were lifted in 2016, Iran increased its oil output by 23 percent, according to OPEC. Tehran reached and even exceeded its pre-sanctions production of 3.7 million barrels per day (bpd), although the reimposition of sanctions derailed its plans to boost output further.

On the export front, even with sanctions relief, Tehran was not able to reach pre-2012 levels, and this will likely remain the case even if the current sanctions are removed. There are several fundamental reasons for this. First and foremost, in the energy industry, it is difficult for an exporter to regain lost market share. Once a producer is out, other actors rush in to fill the vacuum — and they won’t simply give back market share when the producer returns. A second factor is the steady growth of Iran’s domestic oil consumption, which increased by eight percent from 2012-18, even as production fell by five percent. Third, even after sanctions were eased, Washington limited Tehran’s access to U.S. dollar clearing operations, hampering its ability to conduct international trade and depriving Tehran of the funds needed to update its aging oil infrastructure and boost its output. Finally, the collapse of oil prices in 2014-15 also hindered Iran’s ability to overhaul its energy sector. In sum, the performance of Iran’s oil industry in the post-sanctions period was uneven and it did not represent a serious challenge to Russia or other major producers’ interests.

Market geography matters

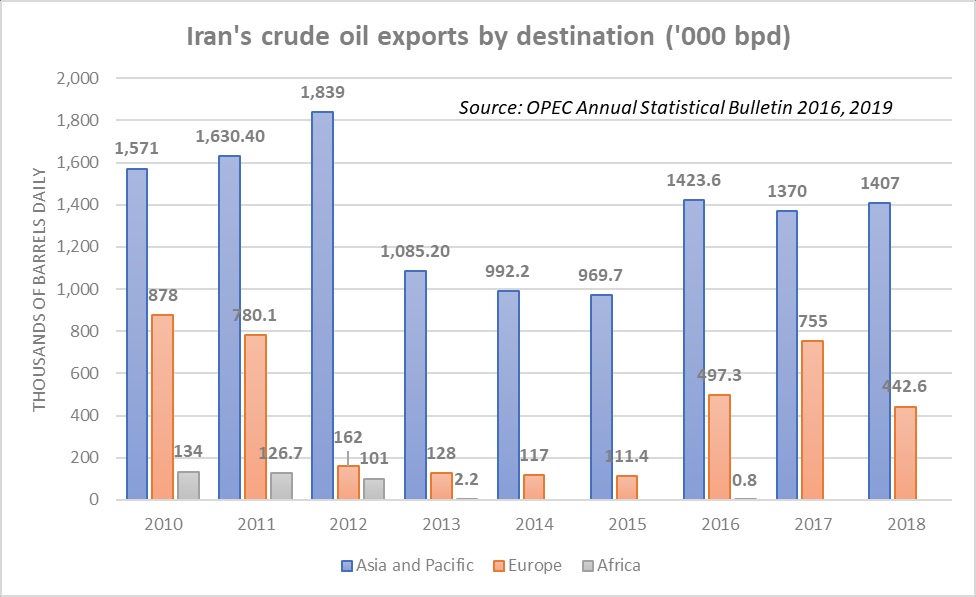

To understand why Iran’s energy exports aren’t a threat to Russia, it’s important to look at export geography. Traditionally, Iran’s major export market is Asia-Pacific. After the signing of the nuclear deal over 70 percent of Iran’s oil went to the region, down from about 90 percent under the previous sanctions. By contrast, Russia’s major export market has long been Europe, where it has supplied about 30 percent of the EU’s crude oil imports for years now. Its share of the EU’s gas imports is even higher, at around 40 percent as of 2018. While Russia’s exports to Asia-Pacific are growing rapidly, Europe is still its major market. As a result, while nominally competitors, the two countries focus on largely different markets — at least for now.

The 2012 oil embargo reduced Iran’s oil exports to all markets. By 2015 its exports to Asia-Pacific fell by 43 percent and to Europe by 87 percent. Even though Europe was the second biggest market for Iran, Russia’s exports of oil to Europe were always several times greater. Moscow has consistently supplied around 3 million bpd to Europe, while Iran’s exports have been around 0.1-0.8 million bpd, depending on sanctions.

After the nuclear deal was struck, Tehran managed to restore oil exports to Asia-Pacific to an average of 1.4 million bpd, 23 percent lower than in 2012. Iran was on track to reach pre-sanctions export levels to Europe in 2017, but was hit by the impact of the U.S. withdrawal from the nuclear deal, which led to a sharp reduction in European demand. Since then, oil from Iraq, Nigeria, and Russia has mostly substituted for the decline in Iranian exports.

One could argue that the 2012 Iran sanctions allowed Russia to increase its share of the market in Asia, in particular in China, but this was more of a happy coincidence for Russia than a driver of its increased oil exports to the region. In fact, Moscow had begun working to boost its exports to Asia well before 2012 due to the region’s stronger economic growth and rapidly expanding demand. In 2011, Russia finished construction of the Eastern Siberia-Pacific Ocean (ESPO) pipeline, which supplies crude oil to China and other Asian markets, leading to a sharp rise, of 146 percent, in its oil exports to China in 2012-17. Also, Russia’s own oil production has been growing consistently for the last several decades. From 2008 to 2018, it increased its output by 10 percent, helping to satisfy domestic demand and still boost oil exports.

2018 game changer

History seems to be repeating itself again, but on a larger scale this time, making it all the more difficult for Tehran to overcome the impact of renewed U.S. sanctions, even though there is much greater international skepticism of U.S. policy this time around.

Nevertheless, the reimposition of U.S. sanctions is having a clear impact on Iran’s oil production and exports. It may not have cut them off completely, as intended, but it has dramatically reduced them. According to OPEC, production has fallen steadily over 2019; as of May it was already down 34 percent compared to 2018. The same is true for exports, which dropped to 500,000 bpd or lower in May, according to industry sources. They have more than halved since the beginning of the year and decreased three-fold compared to 2018.

Compared to the previous U.S. sanctions in 2011-12, the new ones are more severe and have already put considerable economic pressure on Iran, pushing it closer to Moscow in a way that might make Tehran more willing to negotiate with Russia on certain regional issues, like Syria.

Although Russia may well gain from the U.S. sanctions on Iran, it will be a marginal benefit rather than a direct profit. There are upsides though. Moscow has already agreed on a 100,000-bpd crude-for-services swap, which preserves one relatively safe market outlet for Tehran and allows it to continue receiving essential goods. Moscow and Iran have entertained this idea since 2014 but only launched it in 2017. Today, this mechanism is functional, both sides benefit, and the parties are discussing ways to expand it.

Iran finds itself in a paradoxical new reality in which it faces greater economic pressure than ever before, but also enjoys more political support. Even America’s European allies and partners in the Middle East and Asia are unhappy with Washington’s policy and opposed to it. Whether this political support can generate any meaningful economic relief remains to be seen though.

At present, Iran has few good options to manage the sanctions, although there are some tools and mechanisms – such as utilizing the grey market and selling oil at lower prices, among others – that have helped it to ease pressure in the past that might be adapted to this new reality. Nevertheless, Washington’s goal of pushing Iran’s energy exports down to “zero” and the fear among its partners of U.S. secondary sanctions have significantly reduced its room for maneuver.

As for the Russia-Iran dynamic, it seems that the U.S. approach to Tehran is only pushing it closer to Moscow, which in turn is looking for ways to ease the pressure on its partner. For now though, it is not yet clear whether Russia will be able to do much to help Iran cope with the sanctions.