The violent insurgency in the Mozambican province of Cabo Delgado has spurred a mini industry interrogating whether/when/how southern Africa will become a hub for international terror syndicates, in particular the Islamic State. But according to the United Nations Security Council, terror and organised crime are increasingly interconnected. In which case the region has a problem that the insurgency could massively compound.

You turn around to take a final peek

And you see why it’s so unique to be

Among the lovely people living free

Upon the beach of sunny Mozambique

—Bob Dylan, Mozambique

Risk/reward

The elderly man slumps with exhaustion. An unseen assailant jams a pistol into his cheek, while someone else keeps a semi-automatic at his throat. Stripped to his underwear, his eyes puffy from weeping, something about the man’s bearing suggests that, not so long ago, he was powerful and in full control of his destiny. He does not appear accustomed to begging.

“I can’t take this torture anymore,” he says. He is slapped once, twice, a third time. “This will be the last time you see me. Beg, borrow and steal. Give them the money.”

The 72-year-old Indian man, his pleas captured on grainy mobile phone footage, was kidnapped in Johannesburg on his way to work on the morning of 2 July 2020. (His name cannot be revealed in order to protect his identity.) He instantly became a unit of exchange in one of South Africa’s very few growth industries: Kidnapping, Ransom and Extortion, a field so common in gangster states that it has its own widely employed acronym — KRE.

The man’s ordeal would last for almost three weeks, after which he was found alive and unharmed. For this, he must count himself extraordinarily fortunate. The day before his release, on 23 July, five men were arrested at a farm in Kliprivier, Gauteng, and charged with his kidnapping. According to SAPS National Commissioner General Khehla Sitole, the suspects were allegedly responsible for running a KRE ring that spanned South Africa. Among the evidence found at the site was a copy of the ransom video, several “military uniforms” and nine rifles. The cops also found the licence plates of a BMW X5 SUV, identified in CCTV footage recovered from a mass shooting perpetrated minutes after midnight on 1 January 2020 in Johannesburg. The drive-by, which tore up a popular Melville restaurant called Poppy’s, was one of two such incidents that took place over the course of that bloody evening, claiming the lives of two people and leaving 17 injured.

As is the tradition in South Africa, the KRE ring was assigned a bad-ass band name — the “Kliprivier Five”. Then came the bombshell: This was “one of the biggest breakthroughs we have had in our investigations of international terrorism in South Africa,” crowed the authorities, darkly hinting at the insurgency in northeastern Mozambique. Tying their theory together with a menacing bow, the cops raiding the farm found themselves gazing at a Rayat al-Uqab — the “Black Standard” flag that serves as Islamic State’s (IS’s) iconic marker.

If the police had found a Manchester United flag on the premises, would they have suspected the men of being professional football players? Probably not. But adding to the cache of circumstantial evidence was the fact that the suspects, including an Ethiopian and a Somalian, had links to a spate of attacks in KwaZulu-Natal in 2018. These included several bomb scares and a knife attack in the Shia Imam Hussain Mosque in Verulam, which resulted in the death of a mechanic named Abbas Essop, and serious injuries for the mosque’s imam and caretaker. (One of the perpetrators of those attacks is alleged to have moonlighted as a member of the Kliprivier Five.)

The suspects are now being investigated for cryptocurrency trading that dovetails with an assortment of criminal enterprises, the proceeds of which are allegedly funding IS in some capacity. The investigators cannot say which IS branch is benefiting from the suspects’ largesse, nor are they certain what or for whom the weapons cache was intended. But as far as the authorities are concerned, the kidnapping bore the imprimatur of an IS-affiliated cell, one of a number alleged to have been formed in South Africa since 2015.

Does this incident suggest that IS has now firmly established itself inside South Africa, one of the most religiously tolerant countries in the world, with its bustling marketplace of ethnicities and creeds living cheek by jowl in harmonious poverty? As the trouble in Mozambique has exploded into a full-blown geopolitical crisis, so too has an IS think tank industrial complex. Webinars, op-eds, Twitter threads, talking heads, all asking: Is IS really expanding its footprint in southern Africa? If so, how entrenched is it?

And most importantly: How badly will regional governments screw up the response?

What, me worry?

Since 1994, South Africa has transitioned relatively seamlessly from a sanctions-busting fascist regime where organised crime was managed by, and within, the state, to a liberalised gangster economy, where the ruling party functions as one of a number of patronage networks feasting on (dwindling) national, provincial and municipal resources.

This would be dangerous and destabilising enough on its own. But there’s an increasing understanding in global policymaking circles that the dividing line between organised crime and terrorism has all but disappeared, if it ever existed at all. The UN Security Council (on which South Africa sat for the previous session) recently included organised crime in Chapter 7 of the UN Charter, which means that the cast of Sopranos are now regarded as a threat to international peace and security on par with the bad guys in Homeland. By way of example, in June 2020, IS in Syria collaborated with the Camorra crime family in Italy to land about $1.2-billion worth of contraband amphetamine tablets in Naples, resulting in one of the world’s largest pills busts yet. Around the same time, the Security Council unanimously adopted Resolution 2482, which made explicit the union between organised crime and terror. The resolution acknowledged:

[T]hat terrorists can benefit from organised crime, whether domestic or transnational, such as the trafficking in arms, drugs, artefacts, cultural property and trafficking in persons, as well as the illicit trade in natural resources [and] illicit trafficking in wildlife and other crimes that affect the environment, as well as from the abuse of legitimate commercial enterprise, non-profit organisations, donations, crowdfunding and proceeds of criminal activity, including but not limited to kidnapping for ransom, extortion and bank robbery, as well as from transnational organised crime at sea [.]

If that sounds like a travel brochure for South Africa, it’s not by accident: the resolution describes febrile gangster-infested pseudo-states just like this one. Ryan Cummings, a senior analyst at Signal Risk, put it this way: “We basically host the criminal underworld in this country. Which means that this is a major part of the world for extremist groups to use as a financing base for their operations.”

As the ANC has dismantled the mechanisms to effectively battle organised crime — most notably the Directorate of Special Operations (Scorpions), which it binned in 2009 — it has also shied away from acknowledging the threat posed to South Africa, either by domestic or international terrorism. There are reasons for this, the first of which is psycho-political: the ANC was itself designated a terror organisation by the apartheid regime and its allies, most notably the US. The wounds have yet to heal. Furthermore, South Africa has for years positioned itself on the right side of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict (in word if not in deed), and since 2002 has refused to lend its support to Western adventures in Iraq and elsewhere in the Middle East.

If this approach is meant to serve as inoculation, it hasn’t always worked. During the 2010 Fifa World Cup Final, South Africa faced credible threats from a number of terror organisations. At the time, the government ensured that the police, the South African National Defence Force and the State Security Agency coordinated with American and British intelligence services to deliver a peaceable month-long mega-event. It was a collaborative endeavour so effective, according to Anton du Plessis, formerly of the Institute for Security Studies, that it pushed deadly attacks out to Uganda and Kenya, where hundreds of people lost their lives in World Cup-related terror.

But 2010 was a long time ago, and South Africa’s intelligence capabilities have cratered since former president Jacob Zuma repurposed the security cluster as a vessel of graft and personal enrichment. There is, however, no doubt that extremist activity of all flavours occurs on South African soil. White supremacist wannabe terror groups, such as the National Christian Resistance Movement, are vociferous in their opposition to the government, although their war-posturing is more absurd than it is dangerous.

As far as Islamist terror is concerned, the designation unfortunately implies homogeneity and coherence. (This isn’t some wonky moral-relativist stance — as UN Resolution 2482 suggests, there is a real connection between bad definitions and bad analysis.) Since the heyday of the vigilante/terror group People Against Gangsterism and Drugs (PAGAD) and its myriad affiliates in the late 1990s, no similar homegrown organisation has emerged. And while between 60 and 100 South Africans left to join IS during the height of the caliphate in the 2010s, the notion that a super-fundamentalist ideology could ever take root in the South African Muslim community is, frankly, insane.

Pay to slay

And yet, there is a compelling argument to be made for the fact that South Africa is a terror hub, just not of the Afghani variety. When it comes to transnational groups such as al-Qaeda, al-Shabaab or IS, experts tend to break their operations down into two distinct but overlapping components. The first is financial and logistical — the use of a country’s banking and communications systems, formal or informal, to fund and organise terrorist activities. The second is operational — the use of a country as a base from which to conduct operations internally or externally (or in IS’s case, from which to expand its territorial ambitions).

As far as the first point is concerned, “the UN has warned South Africa that its banking institutions and financial system are being used to fund illegal trafficking and terrorism”, says Liesl Louw-Vaudran, senior researcher at the Institute for Security Studies. “The money definitely travels through South Africa.” Not a single expert Daily Maverick spoke with for this story disputed this view.

As for attacks within South Africa, the country has blessedly avoided becoming a major target for such unpleasantness. But there is a dispute among experts about whether IS-affiliated rogue groups have formed here in the past several years. Take the case of Brandon-Lee and Tony-Lee Thulsie — the now-infamous Thulsie Twins — who were arrested in July 2016 during raids in Newclare and Azaadville on the West Rand. Frustrated in their attempts to join IS abroad, they were apparently planning to blow up the US embassy building in Pretoria, along with a number of “Jewish institutions”, including Daily Maverick’s resident cartoonist, Jonathan “Zapiro” Shapiro.

Those were big, sinister plans. But how real was the threat? And how established were the links between these young men and the terrorist organisation they couldn’t join, which at the time maintained a caliphate stretching from Syria to Iraq? These questions have never been successfully answered, and the twins languish in prison without having given up any meaningful intel. That said, a collaborator named Renaldo Smith, who turned State witness against them and fled South Africa in 2018, resurfaced in Mozambique a year later, having apparently joined the insurgency.

Then, in February 2018, Rodney and Rachel Saunders, British botanists who had resided in South Africa since the 1970s, were kidnapped and murdered. Sayefudeen Del Vecchio and his wife Fatima Patel were charged with killing the couple and dumping their bodies in the uThukela River. Jump-cut to the Netherlands, where a man named Mohammed Ghorshid, already on a watchlist due to links with IS, was arrested by the intelligence authorities for trying to purchase bitcoin using a credit card belonging to one of the Saunderses. This was a seemingly clear-cut case of transnational terror funding that also happened to be an example of sloppily executed transnational crime.

Following this came the bomb scares in KwaZulu-Natal, and the eventual knife attacks on the mosque in Verulam. On 13 July 2020, the case against the 12 men allegedly involved in the attacks was struck off the roll in the Verulam Magistrates’ Court for “undue delays by the State”. The men were accused of, among other things, “furthering the aims of the IS”. Various murder manuals, Islamist propaganda and eight Black Standard flags were found in the ringleader’s possession. The whole case has proved hugely controversial, with some observers insisting that the stabbings were an IS-inspired Sunni attack on a Shia religious institution, while others claim that it was a classic KRE shakedown turned nasty. The only thing observers agree upon is the fact that the prosecution massively botched the case, and again we’ll probably never know the truth. (The State has promised to go back to court on this one.)

Still, the alleged links between the Verulam and Kliprivier gangs seem to have thickened the plot. As Daily Maverick Africa correspondent Peter Fabricius has noted: “Some analysts suspect many of these episodes are connected, and that if one joins all the dots, they outline a disturbing picture. Others believe it’s too early to detect a pattern.”

While the hawks and the doves battle over these issues, Jasmine Opperman, Africa analyst at the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, insists that the South African context is unique, and needs to be viewed as such.

“We need to stop comparing ourselves to Europe, the Middle East, or even Nigeria,” she told me. “Logic dictates if IS wanted to gain access to South Africa, organised crime is the route they’d go. South African vulnerability lies in its organised crime syndicates.”

In other words, South Africa is the cast of the Sopranos. All that’s needed is the bad guys from Homeland to blow things sky high.

Poached dregs

In 2011, a South African conservationist named Alastair Nelson was assigned to the Niassa Reserve in northern Mozambique, arguably the most spectacular 42,000 square kilometres of natural wilderness remaining on Earth. More than twice the size of the Kruger National Park and hugging the banks of the Ruvuma River, the reserve was densely forested with miombo woodlands, and hosted an animal population that included African wild dogs, lions and leopards. Niassa nevertheless suffered from what could politely be described as “a poaching problem”. Nelson’s job was to help stem an annual slaughter of 1,000 or so elephants, along with the illegal trade of their tusks.

He soon learnt that the root causes of poaching, along with pretty much every issue in the region, were depressingly banal, if gothically intricate. Niassa Reserve bleeds into northeastern Cabo Delgado, the poorest province in Mozambique, and one of the poorest pockets on Earth. There was almost no formal employment; there was almost no formal development; nearly seven out of 10 residents were illiterate. Locals called their home “Cabo Esquecido”. The Forgotten Cape.

Cabo Delgado is home to a considerable Muslim population that has for years suffered marginalisation and harassment at the hands of the authorities. When kids here came of age, there was nothing for them to do — the province was subject to more of a youth thermonuclear bomb than a youth bulge. Many got sucked into a vortex of boredom, excessive religiosity and organised crime. It’s here that Nelson and a number of other observers saw the exact conditions the UN Security Council warned about when it drafted Resolution 2482: Chaos, poverty and resentment bred an indistinguishable melange of organised crime and terror. To the north, Tanzania, pushing fundamentalists south in a series of pogroms. Far to the south, a sophisticated gangster state known for its terror-funding mechanisms. To the southwest, Zimbabwe, operated by an organised crime entity called Zanu-PF.

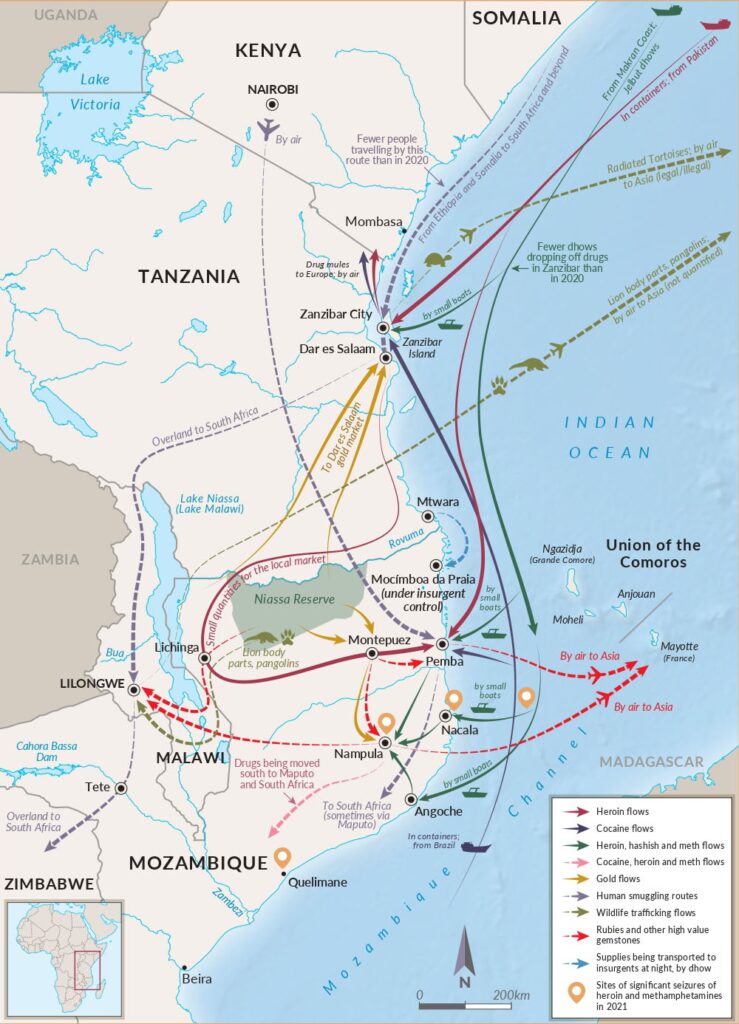

Then there was Mozambique itself: 3,000km of unpoliced coastline resulting in one of the planet’s great organised crime free-for-alls. In Cabo Delgado alone, a booming trade in human trafficking existed along with illicit trade in timber, ivory, rubies and gold, all of it moving over the northern border, while fishing vessels illegally plundered the entire contents of the coastline into oblivion. And, of course, there was Mozambique’s stock-in-trade: Heroin distribution. (Now joined by methamphetamine.)

This was all loosely overseen by former army generals associated with the ruling Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (Frelimo) party, who jealously watched over trade networks that, in some cases, dated back centuries. Corruption was less a socio-political than a metaphysical condition — it was everywhere, always, without respite. “The difference between legal and illegal trade is entirely theoretical,” Simone Haysom, a senior analyst at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, told me. “Heroin is completely vertically integrated into the economy and life.”

According to Mozambique expert Joseph Hanlon, Frelimo has ties to the country’s biggest narco-traffickers: Every year hundreds of millions of dollars worth of heroin lands off the coastline and is shipped by road into Johannesburg, rendering the country a major pit-stop on the Smack Track that connects Afghanistan and Pakistan with Europe. At least $100-million of this revenue is alleged to be kicked back to Frelimo annually.

Until now, the party has functioned as the regulatory force in this trade network, avoiding the narco wars that would arouse the displeasure of their international donors and/or disrupt the patronage cash flow. As far as the heroin entering Mozambican waters is concerned, Frelimo’s end of the deal is allegedly to ensure that the goods are moved from dhows off their coastline, secured in warehouses, and then trucked into Johannesburg, all without molestation.

As far as this trade — and, more critically, access to land — was concerned, Cabo Delgado’s Muslims were all but cut out of the action. These divisions were decades old, and historically forged along ethnic, religious and even party lines. The Muslim population, typically Mwani or Makua, were aligned with the Resistência Nacional Moçambicana (Renamo) during Mozambique’s brutal civil war, while the largely (but not exclusively) Christian Makonde formed Frelimo’s vanguard. Following the war, which lasted from 1977 to 1992, Renamo was routed, the northern Muslim community was neglected, while the Makonde flourished (insofar as anyone flourishes in Mozambique). The resulting inequities have been heightened by the discovery and tentative exploitation of natural resources — first rubies, and more recently, vast deposits of natural gas off the coastline.

Kick-off

Killing elephants in the bush in the dark is nobody’s idea of a dream gig, and the conservationist Alastair Nelson was reminded that a) necessity is the mother of all poaching and b) in a vacuum of governance, all life is cheap. Despite Frelimo’s involvement in the northern gangster economy, and despite the fact that it was tacitly supporting the illicit ivory trade, over the past few years Maputo was hoping to bring Cabo Delgado’s chaos under something that resembled control. It wasn’t all about the gas, but mostly it was: Frelimo was betting the entire country on the bonanza that resulted from massive liquid natural gas finds by the US energy company Anadarko in 2010, and then Italy’s ENI the following year. The gas lay like a golden egg waiting to hatch at the bottom of the Rovuma Basin, which chops its way like an isosceles triangle into Cabo Delgado, just north of Pemba. Total picked up Anadarko’s Mozambique assets in 2019. ENI, ExxonMobil, BP, Shell and the China National Petroleum Corporation are also in play.

President Filipe Nyusi, his ruling elite and their enablers promised a $95-billion-over-20-years windfall — money that would (eventually) trickle down to the People, transforming Mozambique into Abu Dhabi, with better snorkelling. The usual misery quickly ensued: Communities displaced, fishing grounds despoiled, farms flattened. But Western natural gas developers don’t seem to enjoy the optics of strafing villagers with helicopter gunships, and so changes had to be seen to be made.

Nelson’s team began working closely with the government and with devoted locals on the ground to curb the elephant slaughter and save Maputo face from its squeamish foreign donors. Almost on cue, in 2014 he heard whispers of a group that called itself, rather grandly, Ahlu-Sunna Wa-Jama’a (or ASWJ, meaning “adepts of the prophetic tradition and the consensus”)*. They were a young, hardcore Islamist sect that began proselytising in and around the towns of Mocimboa da Praia, Nangade, Montepuez and the provincial capital, Palma. “We were hearing a bit about Islamic fundamentalism, and an associated imam who had one or two AKs. We wondered if they were shooting elephants. But they posed no threat,” Nelson told me.

There is extensive debate regarding the sect’s origin story, and not enough research has been conducted to allow for precision in this regard. (It is notoriously tough to gather information in the north of Mozambique, and journalists have both been disappeared and banned.) What is known is that, in the region, the men were labelled “al-Shabaab”, an (unflattering) reference to the Somali terror organisation to which they had no apparent affiliation. Their brief, at first, was to insult mainstream imams, voicing their displeasure with what they considered “fake Islam”. Demanding the institution of sharia (law), railing against the secular state, their mosques, according to the academic Eric Morier-Genoud, became “counter-societies”, bastions of a seriously radical interpretation of Islam.

Only later did they begin to formalise as a more coherent jihadi organisation. As they did, they met a shoddy but brutal firewall mounted by the Mozambican authorities, urged on by mainstream Islamic leaders, and in some cases supplemented by Russian and South African security contractors.

“The discontent was building, building, building,” Nelson told me.

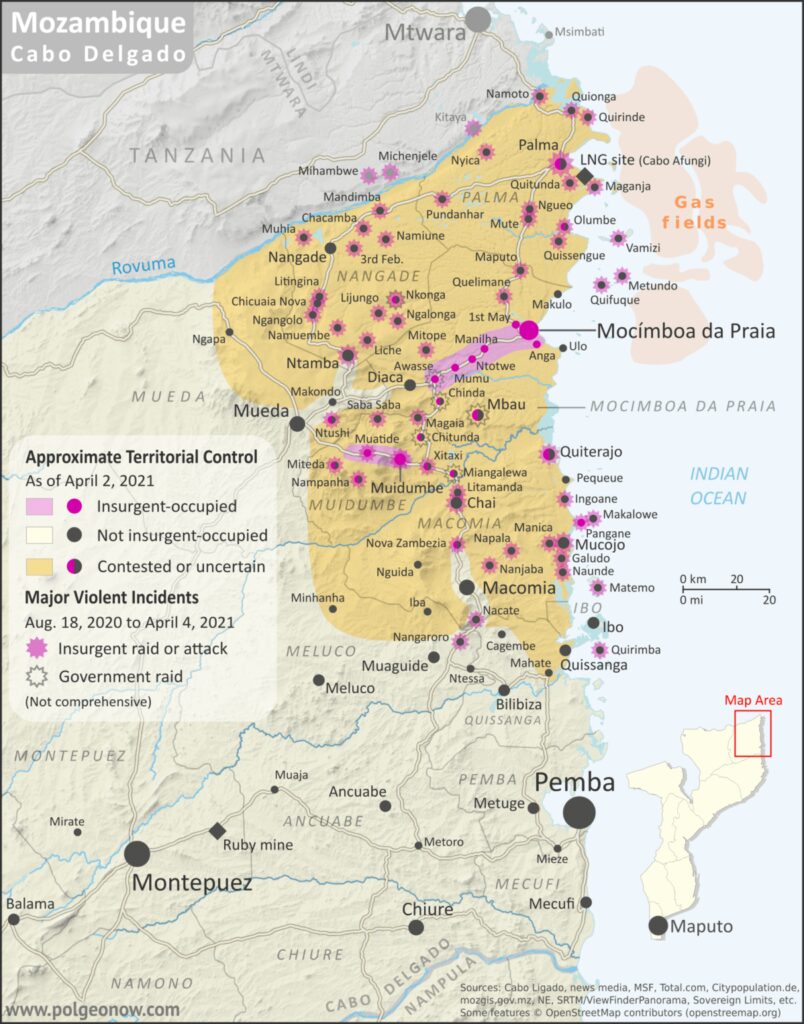

The turning point came on 4 October 2017, when ASWJ hit Mocimboa da Praia with what appeared to be a relatively coordinated, 30-person attack. They held the town for 48 tense hours, only to fade into the bush when reinforcements arrived. Two police officers were killed, along with more than a dozen jihadis.

The insurgency had officially kicked off.

Badfellas

Despite the damage they left in their wake, and leaving aside the Mocimboa da Praia attack, ASWJ was less an organised army than a loose affiliation of guerrilla formations. They recruited an ensemble of street traders from Mocimboa da Praia, jihadis theologically inspired by foreign preachers, and disaffected artisanal (the state would say “illegal”) miners, who worked on the fringes of the Montepuez ruby mine. The development of ruby mining in the early 2010s proved especially contentious, pushing people off their land and cutting locals out of easy procurement deals that went to connected cronies. Locals clashed with the mine’s security forces, so much so that in 2019, Gemfields, the British multinational operating Montepuez, paid almost $8-million to community members to settle claims of human rights abuses.

At first this rag-tag group of jihadis would attack only at night, and then in 2018 they started undertaking brazen daytime assaults. The body count racked up, and massacres became routine. Unsurprisingly, the insurgency never seemed to become broadly popular, and to date more than 700,000 people have fled their homes, traumatised. As was its habit, the government bungled the response, relying on private military contractors for muscle.

The Russian Wagner Group were first responders, who promptly lost seven of their men and fled. Next came the South African Dyck Advisory Group (DAG), whose “advice” included providing air support and allegedly committing human rights violations, which helped push insurgents out of towns like Macomia. Their contract was not renewed, and now the African-based “global aerospace and technology company”, Paramount Group, lends materials and expertise.

In July 2019, the group had its prime time TV moment: ASWJ claimed formal kinship with IS. In keeping with the larger organisation’s nomenclature, it was rebranded as the Islamic State in Central Africa Province, or ISCAP. Nobody wanted to hear this news: Not the Mozambican authorities; certainly not the gas companies plying the Rovuma Basin; and not the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the dozy regional alliance that is more sewing circle than functional multilateral entity.

The massacres intensified, beheadings of children grew routine, the violence grew more violent, and then it happened: On 24 March 2021, the town of Palma, located perilously close to Total’s liquid gas facility, was raided and sacked. The results were straight-to-video horror movie brutal — beheadings, disembowellings, bodies strewn in the streets. Gas contractors fled; private military contractors had to airlift people to safety; the population bolted into the bush. Total has now officially mothballed its $30-billion gas operation. As Nelson pointed out to me, the jihadis hit the town the day before payday, just after rains had ended, and when there was lots of cash circulating.

ASWJ is now flush with guns and money, Mozambique is in nearly irredeemable chaos, and Cabo Delgado is the “forgotten Cape” no longer.

Sleepless nights

What happens next?

That’s the $95-billion question.

Between 15 and 100 South Africans are alleged to have joined ASWJ since its formation, while Zanzibari trading families are suspected of supplying some financing and personnel, along with Kenyans, other Tanzanians and perhaps even some Arabs. Given all the cross-border jihadist tourism, the Mozambican government has attempted to characterise the conflict as an act of foreign aggression, while Mozambican intellectuals and religious scholars have tied themselves in knots trying to cast the insurgency as a (CIA-directed?) conspiracy that has nothing to do with local conditions. This is all bullshit.

While some cash and support have certainly come from abroad; while there are certainly foreigners in the mix; and while the IS link requires serious investigation, there is not a single serious observer who contends that the insurgency was some weird foreign import imposed on languid, sylvan Cabo Delgado. As the researchers Salvador Forquilha and João Pereira have noted, like most African insurgencies, this one resulted “from local dynamics [that], at a certain time, [sought] a connection with global terrorism by promising loyalty”.

There are examples elsewhere that show how poorly this kind of thing can turn out, and how a local conflagration can quickly flare into a regional shitstorm. There has been discussion around whether or not ASWJ will take the shape of Boko Haram in Nigeria, or IS in Syria, or Amazon in the US — at this stage, no one is certain.

On one point there is more or less consensus: For the immediate future, the crisis promises to stay in and around Cabo Delgado. There is, of course, almost no situation in Mozambique that Frelimo can’t make worse, and their tactic of fighting terrorism with terrorism, employing private proxies to do their dirty work, promises to further fuel the insurgency.

What’s more, it would be generous to describe the regional body, SADC, including South Africa, Botswana and Zimbabwe, as “useless”. For almost three years, its members have studiously ignored mentioning the crisis. Now, Zimbabwean President Emmerson Mnangagwa, who earned his genocidal bona fides in the Gukurahundi massacres of the 1980s, has said, “An attack on one of us is an attack on all of us,” and has sent special forces into the region. They will soon be joined by almost 3,000 SADC troops, a genuinely terrifying notion. About this military incursion, Botswana’s International Affairs and Cooperation Minister Lemogang Kwape has said that “It will, most importantly, assist the people of Mozambique to enjoy undisturbed peace, tranquillity and socioeconomic prosperity.”

Irony is clearly not a thing in Botswana.

Could the insurgency spread south, first threatening Maputo, then South Africa, then sideways into Zimbabwe and Botswana?

“How?” asked a nonplussed Alastair Nelson, who is now with Global Initiative. Such manoeuvring would require tanks and bombs and missiles and vast numbers of jihadis, something that ASWJ, even with IS’s logistical assistance, would be unable to muster, and the international community is unlikely to allow. On 10 March, the Americans designated ASWJ a “foreign terrorist organisation”, while former colonial master Portugal has begun forging a bilateral military agreement, and the French navy is lurking in the Mozambican channel.

As for the insurgency hacking its way to Cape Town and taking over the Bootlegger’s franchise? “I don’t know what an Islamist front in South Africa would look like,” Liesl Louw-Vaudran, from the Institute for Security Studies, told Daily Maverick. “Sure, there could be sporadic terrorist attacks. But the IS method is to go into villages, drive out the villagers, behead them, burn down all government buildings and occupy the space. I don’t know how that would be possible in South Africa. The far more credible risk is that there could be isolated revenge attacks if South Africa gets involved in Mozambique. Let’s put it this way: We should at least have a plan.”

Do we?

Factoring in a baseline of total foreign policy incompetence, the South African authorities seem to be taking ASWJ seriously. “The investigation into South African involvement with the insurgency involves Interpol and the Mozambican authorities,” Hawks spokesperson Captain Lloyd Ramovha said in 2020. “The investigation has multiple legs, with detectives looking at cross-border financial flows, the origin of these funds and the involvement of organised crime in raising finances.” Ramovha went on to claim that IS posed no immediate threat to South Africa, despite the fact that the Minister of State Security, Ayanda Dlodlo, insisted the situation was “giving [them] sleepless nights”.

Of far more urgent concern is the fact that the insurgency may prove a disruption to extant illicit networks, causing a whirlwind of knock-on bloodshed. Observers in 2020 believed that, with IS help, ASWJ could take over mafia trading routes. “Now that [the group] controls large segments of the Cabo Delgado coastline, there are fears that they are already beginning to take a slice of illicit coastal smuggling, including taxing drugs cargoes that transit through waters and land they control,” the International Crisis Group’s Dino Mahtani told Africa Report’s Nicholas Norbrook. This would represent a significant shake-up in the southern African narco and human smuggling trades, and new entrants could have major repercussions for the South African end of the supply chain.

That doesn’t seem to have been the case. The Global Initiative recently released a report finding that:

[T]here is little evidence to suggest that illicit economies have in fact become a major source of income for the insurgents. In fact, the insurgent-controlled area and the highly militarized surrounding region have become extremely logistically difficult for trafficking networks to move contraband through. Damage to road infrastructure, the risks of the violence and the presence of government forces have meant that trafficking routes in the region have dramatically changed from those mapped a year ago.

Alastair Nelson doesn’t believe the insurgents are interested in anything so sophisticated as an operational base, at least not at this point. “When I went back up there earlier this year, we found that they’re just a great big [obstruction] stuffed in the illicit flows, so everything is still moving, and they’re not tapped into any of that,” he told me. “So, from an illicit flow perspective, all they’ve done is displace and changed the logistics equations for all those involved, and added a cost to the transport side of things.”

Like a number of other observers, Nelson envisions ASWJ trying to hold and consolidate and perhaps expand its “counter-society” — an Islamist utopia in northern Cabo Delgado, centred on the territory in Mocimboa de Praia that they currently hold. But the IS affiliation may not allow for a stay-at-home policy, and ASWJ may be forced to absorb foreign fighters with differing ecclesiastical sensibilities, who see an opportunity to expand territory and earn significant revenue. This internal conflict — almost inevitable in jihadi groups, historically speaking — will be fought against the backdrop of the gas fields, now that there’s a big, Total-shaped hole to be filled.

Full Gas

The gas fields of northern Mozambique will ultimately be exploited. At question now is: By whom, and how successfully? As one source with knowledge of the situation told me: “South Africa has always had an interest in the gas, and they feel left behind by everyone jumping on the fields up there. There may even be South African ministers who have an opportunity to benefit. The insurgency is giving them an opportunity, upping the costs for everyone else. They’d help Frelimo, and win something, and get some major benefits.”

This, of course, is classic ANC: Business first, national interest last. Human lives? Not even a consideration. Investing in the gas fields would necessitate protecting them. This could prove an echo of the debacle in Central African Republic, where in 2013 South African forces were drawn inadvertently into a civil war, and 13 servicemen lost their lives, allegedly for ANC business interests. The script for a bad Africa Magic action movie basically writes itself.

Because, after all, Cabo Delgado doesn’t need new investors, more militarisation, or — for the love of anyone’s god — South African vulture capitalists. It requires development, it requires rapprochement between the Muslim community and the government, it requires a viable social contract, and it requires rule of law.

“Yeah, I don’t see a positive trajectory,” Simone Haysom told me. “To the degree that a military response will help, it will take a long time for the Mozambican army to become effective. They don’t seem to want outside help, and I don’t think it would be helpful. Nothing will work until there is a paradigm shift in how Frelimo treats the north. Besides, they won’t have a realistic conversation on the origins of the insurgency, and so can’t design a counter-strategy.”

Until that happens, chaos theory will determine how all of this plays out in southern Africa. The opportunities for organised criminals, state-sponsored or otherwise, have never been greater. This will mean revenge attacks, copycat micro-insurgencies, and more old men staring into cellphone cameras, begging for their lives. The age of gangster terrorism south of the Ruvuma River has begun.