The Syrian jihad presented invaluable opportunities for

The Syrian jihad presented invaluable opportunities for

al-Qa`ida to establish what it had always sought: a popular,

broadly representative jihadi resistance movement

that could support the creation of an Islamic government

presiding over an expanse of important territory. Jabhat

al-Nusra assumed the mantle of responsibility in seeking

to achieve this grand goal. And it did remarkably well, up

to a point. As conflict dynamics evolved, however, the goal

of transforming into a mass movement with social and political

popularity became an increasingly distant objective.

In its determination to aggressively achieve its grand goals,

Jabhat al-Nusra prioritized localism over globalism, which

as time passed, pushed its relationship with al-Qa`ida to

the breaking point.

To confront … blatant aggression and brutal occupation,

it is absolutely vital to unite on the basis of Tawhid,

[to] organize our ranks to fight in the way of Allah,

and [to] transcend our disagreements and disputes …

We must understand that we are in for a long war, a

battle of creed and awareness before weapons and combat; a battle

for the sake of upright conduct, inculcating ethics and abstinence

from this world … So let us cooperate, come closer, join ranks, correct

mistakes and fill the gaps.

This is a clear-cut order from me to our brotherly soldiers of

Al-Qaeda in the Levant, to cooperate with your sincere Mujahid

brothers—those who agree with you as well as those who disagree

with you—for the sake of Jihad and fighting the Baathists, Safavid

Rawafidh, Crusaders and the Khawarij.1

Those were the words of al-Qa`ida’s General Leadership, issued

within a stern directive on January 7, 2018, and intended for

a jihadi audience in Syria. There, al-Qa`ida’s prospects for success

have faced existential challenges in recent years. Now, al-Qa`ida’s

claim to command any Syrian affiliate stands on the thinnest of

foundations, if any at all. Instead, the once-dominant al-Qa`ida

affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra embarked on a series of rebrands through

2016-2017 that although intended to further its long-term objectives,

served only to engender crippling internal divisions and a de

facto break from al-Qa`ida. After a months-long public feud pitting

Jabhat al-Nusra’s successor, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), on the

one side against al-Qa`ida and its loyalists in Syria on the other,

mediation efforts energized by prominent al-Qa`ida ideologues and

Shura Council members managed to secure three days of détente in

January 2018—though that soon crumbled.

In fact, the al-Qa`ida statement’s clear acknowledgement of two

distinct factions of fighters—the soldiers of al-Qa`ida in the Levant

(junud qa’edat al-jihad fi’l Sham) and the sincere mujahid brothers

(al-mujahideen al-sadiqin)—was the group’s first public admission

that al-Qa`ida and HTS had become two separate entities.a That

admission underlined how divisive Jabhat al-Nusra’s recent evolution

had been, significant enough to catalyze the formation of an

entirely separate al-Qa`ida loyalist entity.

It is undoubtedly true that al-Qa`ida’s reversal of fortunes in

Syria was, in part, a consequence of shifting conflict dynamics, as

Russia’s September 2015 intervention turned the tide of regime

losses and secured a series of consequential military victories, including

in Aleppo. That reality, coupled with the West’s tunnel-like

fixation on combating the Islamic State and increasing political

fatigue with backing the anti-Assad effort, had combined through

2016-2017 to create conditions in which al-Qa`ida could no longer

benefit from intense levels of conflict (which had given it its

best chance to acquire credibility) and a viable, potent revolutionary

opposition (which it had embedded into and partnered with to

consolidate its credibility).

It was facing these far less favorable conditions that had prompted

an internal discussion around a need to use additional methods

to secure popular acceptance and support. After all, as Jabhat

al-Nusra had repeatedly explained,2 achieving its ultimate objective

of establishing an Islamic state in Syria would only ever be feasible

if it could acquire a sufficiently large and broad spread of support

from those living in its midst. The primacy of military conflict

through 2012-2015 may have allowed for Jabhat al-Nusra’s rise to

prominence and acquisition of some popularity, but shifting dynamics

in 2016 meant additional methods were needed to sustain

and grow existing support.

Central within this challenge was one issue: could a self-identified

al-Qa`ida affiliate broaden its support base to the extent necessary

not only to negotiate a broad-spectrum merger (not alliance)

with Syria’s armed opposition but to secure widespread support for

a jihadi government? Making use of information released publicly

by involved jihadis as well as deeper insight provided to this author

by individuals directly and indirectly involved in Jabhat al-Nusra’s evolution since 2016,b this article seeks to tell the story of how and

why al-Qa`ida has seen its Syrian affiliate slowly drift out of its

control and what that means for its project in Syria.

From Jabhat al-Nusra to JFS

As international diplomacy intensified in early 2016 toward the first

of several nationwide ‘cessations of hostility,’ Jabhat al-Nusra convened

unity talks with opposition factions based in northern Syria.3

Pressure was rising inside Syria’s revolution to adapt to changing

circumstances. Politics were beginning to trump military affairs,

and the Syrian opposition’s external backers were coercing their

proxies to play along. For Jabhat al-Nusra, an avowed al-Qa`ida

affiliate opposed to any foreign manipulation of events inside Syria,

this state of affairs represented a potentially existential threat. The

unity negotiations that began in January 2016 were Jabhat al-Nusra’s

way of preempting any foreign attempt to co-opt its military

partners into acting against its interests. After all, the United States

and Russia were also intensively negotiating to establish a joint intelligence

cell in Jordan to deal specifically with Jabhat al-Nusra’s

‘marbled’ presence within opposition areas.4

As it happened, Jabhat al-Nusra’s best attempts to convince opposition

groups that a full organizational merger was in their best

interests resolutely failed. One reason for rejection hovered above

others: Jabhat al-Nusra’s affiliation and loyalty to al-Qa`ida. As far

as Syria’s mainstream opposition was concerned, their revolution

was under increasing pressure both from within and outside Syria;

now was not the time to risk further alienating the cause by uniting

with a terrorist group, no matter how valuable a military partner

it might be.

This was not the first time that Jabhat al-Nusra’s attempt to encourage

a broad inter-factional merger had failed, but the circumstances

surrounding the collapse of this round catalyzed something

new. Concerned about recent developments, a number of senior

Jabhat al-Nusra commanders coalesced in secret in June 2016 in

a series of meetings organized in part by former senior member

Saleh al-Hamawi. Originally one of Jabhat al-Nusra’s seven founding

members, al-Hamawi had been expelled from the group in July

2015 for his overly ‘progressive’ views.5 Al-Hamawi and his secret

cohort, which included Jabhat al-Nusra’s military chief in Aleppo,

Abdullah al-Sanadi, believed the time had come to sever ties with

al-Qa`ida in order to broaden the appeal of Jabhat al-Nusra’s jihadi

project so as to better secure the kind of unity that might save

their armed struggle from being slowly strangled from the outside.

Al-Hamawi confirmed his role in the process to this author in July

2016, explaining that it would amount to an ultimatum to Jabhat

al-Nusra leader Abu Mohammed al-Julani:

Soon, there will be an ultimatum made to al-Nusra: either disengage

[from al-Qa`ida] and merge with major Islamic factions, or face

isolation socially, politically and militarily.6

Were al-Julani to refuse to consider breaking ties, up to a third

of Jabhat al-Nusra’s fighting force were loyal to the reformist wing,

one informed source also told the author at the time. A name had

even been selected for the potential defecting faction: the Syrian Islamic Movement (al-harakat al-souriya al-islamiyya).7

The interlinked issues of al-Qa`ida affiliation, inter-factional

unity in Syria, and Jabhat al-Nusra’s goal of establishing an Islamic

state had been discussed within jihadi circles in Syria since

at least 2014. Despite their geographic and communications distance,

al-Qa`ida’s central leadership had also begun to weigh in. In

a speech released in May 2016 but likely recorded early that year,

Ayman al-Zawahiri had urged jihadis in Syria to unite, stressing

the objective of establishing a “Muslim government” and indicating

that formal affiliations (to al-Qa`ida) would no longer apply only

if and when such a goal could be achieved.8 Preemptively breaking

ties, however, would not protect jihadis from international counterterrorism

scrutiny, and if they were to break ties early, further

attacks would be inevitable. Though some of the wording may have

appeared ambiguous to some, the logic was clear: do not break your

bay`a (oath of allegiance); your goals have not been met.

Events in Syria were moving rapidly, and al-Zawahiri was too

far away to influence directly what was, for Jabhat al-Nusra and its

leadership, an issue needing urgent attention. According to multiple

senior Jabhat al-Nusra and Islamist sources inside Syria who

spoke to this author both at the time and since, al-Julani convened

an initial, urgent meeting of his Shura Council in mid-July 2016

to discuss the issue of al-Qa`ida ties and how best to continue to

pursue Jabhat al-Nusra’s objectives in Syria. That meeting ended

in discord when it became clear that the Shura Council was divided

on the issue.

As the Shura members dispersed and retreated to their respective

hideouts, the debate continued behind multiple closed doors

and attracted a broader circle of people, these sources told the author.

A number of different camps emerged. Some determined that

protecting Jabhat al-Nusra’s achievements in Syria and proceeding

further toward a united Islamic government made a major break

and rebrand from al-Qa`ida necessary. Some insisted that any

breaking of ties would be wholly illegitimate without the permission

of al-Qa`ida leader al-Zawahiri, his deputies, and the broader

Shura Council. And others proposed a middle-way, in which Jabhat

al-Nusra would sever its ties of allegiance to al-Qa`ida outside Syria,

while retaining close, consultative contact with al-Qa`ida leadership

figures inside Syria. The latter option, its proponents insisted,

would be presented to the world as a full breaking of ties in the

hopes of justifying or legitimizing whatever united body might then

result.

As pressure mounted and details of the controversy were leaked

(including to this author), al-Julani reconvened a significantly expanded

Shura Council, which now included two further levels of

the group’s religious and military commands. According to the author’s

Islamist and al-Nusra sources in Syria, as that larger Shura

met several times through mid- and into late July 2016, al-Julani’s

hyper-loyal deputy, Abdulrahim Atoun (aka Abu Abdullah al-Shami),

began consulting with prominent al-Qa`ida ideologues outside

Syria (including Issam Mohammed Tahir al-Barqawi, aka Abu Mohammed

al-Maqdisi, in Jordan) and with senior al-Qa`ida figures

in Syria. The latter included global deputy leader, Abdullah Mohammed

Rajab Abdulrahman, aka Abu al-Khayr al-Masri (a veteran

Egyptian jihadi with longstanding close ties to al-Zawahiri);9

Khaled Mustafa Khalifa al-Aruri, aka Abu al-Qassam al-Urduni (a

former deputy to Abu Musab al-Zarqawi),10 and Ahmed Salameh

Mabruk, aka Abu al-Faraj al-Masri (a veteran Egyptian jihadi also

previously close to al-Zawahiri)11 on the feasibility of pursuing the middle-way option.

What appears to have resulted from these consultations was a

general permission for Jabhat al-Nusra to pursue the middle-way—

that is, breaking external ties—to protect its project in Syria and

to improve the chances of achieving the Islamic government that

al-Qa`ida had so long sought. Abu al-Khayr, Abu al-Qassam, and

Abu al-Faraj all qualified their permission by insisting that if al-Zawahiri—

who was out of contact—later rejected the move, they too

would retrospectively oppose it, and Jabhat al-Nusra would have to

reverse its decision. Al-Julani, Atoun, and others reportedly agreed

to these terms, and the proposal was made to a final meeting of

the expanded Shura on July 23, 2016. The debate that followed

was tense, and a number of Jabhat al-Nusra’s most senior leaders

balked at the proposal. At least one, Iyad al-Tubasi (aka Abu Julaybib),

stormed out of the meeting. Nevertheless, a slim majority

ultimately voted in agreement.12 Jabhat al-Nusra began preparing

a major announcement.

Five days later, on July 28, 2016, in a brief audio statement, Abu

al-Khayr al-Masri gave al-Qa`ida’s blessing for Jabhat al-Nusra’s

breaking of ties. At the end of his message, he included a previously

unreleased audio clip from al-Zawahiri stressing that organizational

links should be sacrificed if necessary for unity, creating the

impression that al-Qa`ida’s leader had also sanctioned the move

himself.c

Shortly thereafter, al-Julani, Atoun, and Abu al-Faraj appeared

on video—al-Julani revealing his face for the first time—and announced

the dissolution of Jabhat al-Nusra and the establishment

of Jabhat Fateh al-Sham (JFS), a jihadi movement devoid of “external

ties” and dedicated to forming “a unified body” in Syria to

“protect” and “serve” its people.13 In the days that followed, JFS’

eloquent, English-speaking spokesman Mostafa Mahamed (Abu

Sulayman al-Muhajir) sold the move to the Western media as a

complete break from al-Qa`ida driven by a determination to focus

solely on Syrian issues and to secure broader unity with opposition

factions:

[Before this change, Jabhat al-Nusra] was an official branch of

al-Qaeda. We reported to their central command and we worked

within their framework; we adhered to their policies. With the formation

of JFS, we are completely independent. That means we don’t

report to anyone, we don’t receive directives from any external entity.

If dissolving external organizational affiliations or ties will

remove the obstacles in the way of unity, then this must be done.

When we were part of al-Qaeda … our core policy was to focus all of

our efforts on the Syrian issue. That was our policy before and it will

be our policy today and tomorrow.14

This was al-Julani’s gamble.15 Faced with severe internal pressure

to consider a move that he personally had repeatedly refused, al-Julani had now decided to take a leap into the unknown in hopes

that doing so would be enough to overcome the trust gap with Syria’s

opposition and secure its willingness to merge and then its backing

to establish a unified Islamic political project.

JFS: Rising Tensions

Despite the grand nature of JFS’ emergence, the movement’s birth

was not altogether smooth. In fact, several of Jabhat al-Nusra’s

most senior figures were furious. Abu Julaybib—a former close

aide to Abu Musab al-Zarqawi16—publicly quit JFS in August 2016

in protest at the “disengagement” from al-Qa`ida.17 He was later

followed by two other senior leaders, Abu Khadija al-Urduni and

Abu Hammam al-Shami, who opposed what they saw as the ‘dilution’

of jihadi purity.18 Jabhat al-Nusra’s former deputy leader Sami

al-Oraydi chose not to quit JFS altogether, but he refused to take

any position of responsibility. At least 11 other senior Jabhat al-Nusra

figures adopted similar positions.19

Almost as soon as JFS came into existence, this band of detractors

emerged as a thorn in al-Julani’s side. Their mere existence

was compounded by a private letter that arrived in late September

2016 from al-Zawahiri in which he angrily chastised al-Julani and

called the rebrand to JFS an “act of disobedience.”20 Al-Zawahiri

explained that such a move could only occur after an Islamic state

was established, and even then, it would need the approval of al-Qa-

`ida’s entire Shura Council.21 In a separate message that came with

the secret letter, al-Zawahiri also admonished his global deputy Abu

al-Khayr for giving his permission to al-Julani.22 Shortly thereafter,

as he had warned he might, Abu al-Khayr reversed his support for

JFS’ creation, leaving the ball in al-Julani’s court. Al-Julani was now

expected to dissolve JFS, reassert his allegiance to al-Qa`ida, and

reestablish Jabhat al-Nusra.23

Notwithstanding the Syrian opposition’s continued skepticism

that JFS was anything different to Jabhat al-Nusra, the arrival of

al-Zawahiri’s letter caused shockwaves. Al-Julani’s gamble was already

facing serious challenges, and its internal detractors now had

the greatest piece of ammunition possible. By this time, it had also

become clear, after communications had been established to Iran,

that two other veteran al-Qa`ida senior leaders living there—Mohammed

Salah al-Din Zaidan (Saif al-`Adl) and Abdullah Ahmed

Abdullah (Abu Mohammed al-Masri)—had also rejected the rebrand.

d

Rather than abiding by his initial assurances to al-Qa`ida’s

senior representatives, however, al-Julani refused to reverse JFS’

formation and external break from al-Qa`ida. Instead, he hurriedly

convened a meeting of JFS and al-Qa`ida leaders in the Idlib

town of Jisr al-Shughour on October 3, 2016, in which he and his

loyal comrade Atoun sought to convince those in attendance of the

importance of standing firm and correcting al-Zawahiri’s ‘misundderstanding.’24 According to Atoun, the al-Qa`ida figures jumped

to al-Julani’s defense, claiming that al-Zawahiri must have misunderstood

JFS’ nature and the circumstances surrounding its creation.

25 Other than Atoun’s biased claims, though, no other evidence

has emerged proving that al-Julani was so strongly defended. Abu

al-Faraj’s death in a drone strike an hour after the meeting further

added to tensions, according to one HTS-linked source who met

some of the attendees afterward.26

Throughout the remainder of 2016, pressure continued to

mount on JFS and al-Julani. The first attempt to negotiate a merger

with opposition factions since JFS’ formation precipitously broke

down in mid-August, due to continued concerns about the group’s

al-Qa`ida connections and objectives. After only six weeks, the rebrand

was not going to plan. Moreover, by late September 2016,

JFS had grudgingly evacuated all its positions in northern Aleppo

in protest to Turkey’s “Euphrates Shield” intervention against the

Islamic State and the Kurdish YPG. Al-Julani was then forced to

watch almost all Syrian opposition groups sign on to a major ceasefire

on September 13 enforced by the international community that

provided for possible U.S. or Russian strikes on JFS.

In a series of undisclosed meetings in September 2016 with

Turkish security officials in Ankara, an armed opposition delegation

then considered lending intelligence support to U.S. drone

strikes on al-Qa`ida figures in exchange for Turkish oversight on

the targeting process, two attendees told the author.27 Though the

outcome of those meetings was left ambiguous, U.S. strikes against

veteran al-Qa`ida members as well as leading JFS figures steadily

increased in northwestern Syria from September into the winter

of 2016-2017.e

Having embraced the role as JFS’ public defender-in-chief,

Mostafa Mahamed’s October 17, 2016, ‘resignation’ from JFSf was

the first sign of discontent within the group’s ‘dovish’ wing. Protest

was now coming from both ends of the spectrum. To make matters

worse, al-Julani was then forced in October 2016 to come to the

defense of a particularly troublesome front group, Jund al-Aqsa,28

which a recent opposition investigation had accused of working

for the Islamic State.g That opened up an uncontrollable can of

worms in which Ahrar al-Sham, which had repeatedly dissolved

recent merger talks with Jabhat al-Nusra and JFS, and others led

a military campaign to eradicate Jund al-Aqsa. Having secretly established

Jund al-Aqsa in early 2013 as a front to take in Jabhat

al-Nusra’s foreign fighters and shield them from recruitment attempts

by the emerging Islamic State group, al-Julani’s sense ofloyalty saw him subsume and protect a force otherwise viewed almost

universally with hostility. Even when Jund al-Aqsa suicide car

bombs targeted Ahrar al-Sham bases, as in Saraqeb on October 10,

2016, JFS took to misinformation, claiming instead that airstrikes

were the culprit.29

From JFS to HTS: Aggressive Expansion

As 2016 drew to a close, rumors abounded that al-Qa`ida had

lost patience with al-Julani and that Abu Julaybib was laying the

groundwork for a new loyalist al-Qa`ida faction known as “Taliban

al-Sham.”30 Leading jihadi ideologue Abu Mohammed al-Maqdisi

also launched a public critique of JFS, questioning the “diluters’”

(al-mumayi’a) motives in degrading the purity of Jabhat al-Nusra’s

methodology (manhaj).31

Having pushed through the rebrand based on the gamble that it

would secure a mass merger in Syria, al-Julani began preparing for

a final try in November 2016. According to three members of Ahrar

al-Sham and an Islamic cleric close to HTS, those preparations

included a lobbying effort within Ahrar al-Sham to undermine the

group’s most nationalistic wing, which had consistently vetoed a

merger.32 Eventually, Ahrar al-Sham’s internal divisions on the issue

erupted when an extremist wing favoring closer ties with JFS and

calling itself Jaish al-Ahrar announced itself as a “sub-faction.”33 In

effect, Jaish al-Ahrar and its leadership—including Ahrar’s former

leader Abu Jaber al-Sheikh, military leader Abu Saleh Tahhan, and

Kurdish Islamic advisor Abu Mohammed al-Sadeq—were positioning

themselves as an ‘almost-splinter group,’ in case unity talks with

JFS again failed.

The merger talks began in December 2016, and although an

initial agreement was signed by Ahrar al-Sham’s then-leader Ali

al-Omar,34 it later fell apart when a majority of Ahrar’s leadership

again refused.35 They were especially concerned about JFS’ lack of

ideological change; recent death threats made in the event of ‘no’

votes; and a fear of losing external support, particularly from Turkey.

36 The failure of the talks was the straw that broke the camel’s

back. By January 2017, JFS and Ahrar al-Sham were engaged in

violent conflict in northwestern Syria.37 Although Ahrar refused to

attend the first round of the controversial Astana talks co-hosted by

Russia, Iran, and Turkey, it expressed support for those who did.38

The January 2017 JFS-Ahrar conflict had been preceded by coordinated

JFS attacks on several Free Syrian Army (FSA)-branded

groups in Idlib and western Aleppo,39 which severely damaged its

reputation within the broader opposition. The Turkey-based, mainstream

Syrian Islamic Council (SIC), which retains close relations

with almost all northern Syria’s opposition, even called for fullscale

mobilization against JFS, labeling al-Julani’s group “khawarij”

40—the same term commonly used to refer to the Islamic State’s

ultra-extremist breakaway tendencies. Throughout the fighting,

which was clearly designed to undercut allies and neutralize future

threats, JFS sought to defeat some of the most popular FSA factions

Image captured from an HTS video entitled “The Battle to Liberate al-Mushirfa and Abu Dali Villages,”

which was produced by “Amjad Foundation for Video Production” and released in December 2017

within the CIA-led assistance program,h claiming it was preempting

a foreign “conspiracy” against its forces.41 JFS also aggressively

sought control of important areas along the Turkish border, including

the Bab al-Hawa crossing—an invaluable source of income and

a potent source of control over the fate of rivals in Syria’s northwest.i

The key consequence of this unprecedented spate of inter-factional

fighting was a clarification of the line distinguishing Ahrar

al-Sham and JFS, with a series of substantive defections and

mergers taking place between sub-factions of the two groups. On

the one hand, Ahrar al-Sham lost approximately 800-1,000 defectors

to JFS, but gained at least 6,000-8,000 more42 from the

integration into its ranks of Suqor al-Sham, Jaish al-Mujahideen,

Tajamu Fastaqim Kama Umrit and the western Aleppo units of

Al-Jabhat al-Shamiya, and the Idlib-based units of Jaish al-Islam.

On the other hand, JFS lost at least several hundred fighters to

Ahrar al-Sham, while securing 3,000-5,000 additional fighters43

from a merger with Harakat Nour al-Din al-Zinki, Liwa al-Haq,

Jaish al-Sunna, and Jabhat Ansar al-Din. With this expansion, JFS

announced a second rebrand on January 28, 2017, to Hayat Tahrir

al-Sham (HTS).44

HTS Comes Under Fire

This ‘great sorting out’ was the consequence of al-Julani’s aggressive

determination to neutralize potential threats within northern Syria’s

opposition; to deter or preempt externally driven ‘conspiracies’ against his forces; and to catalyze the necessary conditions for an

absorbing of other groups. Although al-Julani arguably succeeded

in achieving all three objectives, the methods used irreversibly damaged

his movement’s standing in the broader rebel movement and

the feasibility of ever transitioning into a truly representative, mass

movement. Consequently, Syria’s opposition communities began

referring to the group as “Hitish”—a use of the “HTS” acronym in

Arabic and purposefully denigratory given its audible similarity to

the Islamic State’s pejorative acronym-based nickname, Daesh. Sizable

protests against the jihadi group also became the norm.

This second rebrand in six months also proved to be the final

nail in the coffin in al-Julani’s relationship with al-Qa`ida. Whether

al-Julani had intended for JFS’ creation to represent a total break

from al-Qa`ida or not had now become a largely academic debate,

as al-Qa`ida and its loyalists began to view HTS as an independent

jihadi outfit—and one that had become so by illegitimately breaking

its strict oath of bay`a.

Al-Maqdisi was again the first to weigh in following HTS’ creation,

warning on January 30, 2017, that “the influence of the diluters

… is now growing greater!”45 Three days later, al-Maqdisi called

on HTS’ leadership to clarify its manhaj, and two days after that,

he called on HTS to urgently clarify “your disavowal of wicked coalitions

such as Euphrates Shield … your disavowal of conferences

and conspiracies like Astana … your views on … secular regimes

[and] foreign backing.”46 Amidst this intensifying public controversy,

Sami al-Oraydi and a close aide, Abu Hajar al-Shami, both

quit HTS on February 8, 2017, citing the second rebrand as the final

straw. Hours later, al-Oraydi proclaimed that “among the greatest

forms of disobedience is disobedience to the mother organization.”

As Cole Bunzel has pointed out, al-Oraydi had used that line before,

in September 2015 in reference to the Islamic State’s criminal

behavior and break from al-Qa`ida.47 Al-Julani and HTS were now

being openly compared to the Islamic State by al-Qa`ida loyalists.

Al-Oraydi’s public exit from HTS and al-Maqdisi’s escalating

criticism sparked a defensive retort by al-Julani’s loyal defender

Atoun on February 10, 2017. In a 20-page screed posted on Telegram,

Atoun accused al-Maqdisi of spouting inaccuracies based on

a lack of information and of failing to make use of JFS’ attempts to consult him on issues related to rebranding. Atoun also explained

that some of the strategic issues internally considered by JFS and

HTS necessitated nuance, rather than a black-and-white lens. For

example, Atoun implied that different opinions existed on issues

like the legitimacy of Turkey’s President Erdogan and relationships

with foreign governments. Atoun strongly rejected al-Maqdisi’s

claim that “diluters” had weakened HTS’ manhaj. HTS was loyal

to “the same principles as before,” Atoun insisted.48

Having been publicly critiqued by his junior, al-Maqdisi responded

boldly on February 14, 2017, charging Atoun with skirting

around important issues and, more seriously, having deceived him

and others about the nature of Jabhat al-Nusra’s rebrand to JFS. According

to al-Maqdisi and despite claims otherwise, Jabhat al-Nusra

had failed to secure permission for JFS’ creation from al-Qa`ida’s

leadership, and in initial consultations he had with Atoun in July

2016, the latter had personally described the potential rebrand as

“superficial” and something that would be reversed should al-Zawahiri

turn out to oppose it. Al-Maqdisi was now implying that the rebrand

to JFS had been conducted with a genuine intention to break

ties, especially given the nature of the second transition to HTS—a

group he claimed had eroded its manhaj, given its emphasis on “liberation”

(tahrir), instead of the more religious “conquest” (fath).49

Although Jordanian jihadi ideologue Abu Qatada al-Filistini

hurriedly stepped in and mediated a détente between al-Maqdisi

and Atoun, the issue had now become very public. Moreover, despite

remaining loyal to al-Qa`ida’s side of the debate, Abu Qatada

grudgingly admitted several weeks later that one needed to celebrate

the fact that a new “jihadi current” was emerging that prioritized

“a project of the Islamic community” over and above a more

exclusivist “ideological group” project. This was a clear reference to

efforts by groups like HTS to broaden their appeal by focusing on

the local and thus, being more willing to make ideological concessions

for the sake of securing mass appeal.50

In mid-February 2017, amidst the al-Maqdisi-Atoun spat, a

meeting of senior al-Qa`ida figures was convened in Idlib to discuss

HTS’ formation and how to deal with the fallout. Al-Qa`ida deputy

leader Abu al-Khayr attended, as did al-Oraydi, Abu Julaybib,

Abu al-Qassam, and Abu Hammam. According to two individuals

attuned to the meeting’s attendees and its outcome,51 those in the

room unanimously opposed HTS’ creation but disagreed on the

path forward. Alarmingly for many in attendance, Abu al-Khayr

admitted that he was never consulted about JFS’ evolution into

HTS, and in fact, he had not met with any JFS or HTS leader for

six weeks.52 That revelation strongly suggested that JFS no longer

considered itself bound by al-Qa`ida’s constraints—again, whether

the Jabhat al-Nusra-to-JFS rebrand was intended to fully break

ties or not.

Abu al-Khayr’s death in a drone strike on February 26, 2017,

served to remove another possible obstacle from under HTS’ feet,

but also emboldened al-Qa`ida’s loyalists further. Al-Oraydi, the

onetime deputy leader of Jabhat al-Nusra, led the charge this time

with a series of public postings through March and April accusing

HTS of sowing division (fitna) within the Syrian jihad by embracing

nationalism over Islam, breaking its bay`a to al-Qa`ida through

the use of “legal trickery,” and insisting that al-Julani’s behavior was

no different to the Islamic State’s betrayal. In what was then unlikely

to be coincidental timing, al-Zawahiri released a statement on

April 23, 2017, (three days after al-Oraydi’s final message) in which

he warned his followers to remain loyal to the global jihad, to resist

attempts to prioritize “nationalist” war, and to engage in guerilla warfare rather than territorial control. Though he made no direct

reference to HTS, al-Zawahiri’s intention was clear. After all, everything

he warned against defined HTS’ strategy. Unsurprisingly,

al-Oraydi responded to al-Zawahiri by describing his message as

being “as clear as the sun.”53

The Great Syrian Jihadi Breakup

Al-Zawahiri’s April 23, 2017, statement appeared to temper tensions,

or at least stop disagreements from being aired publicly.

Al-Oraydi and fellow al-Qa`ida loyalist Abu al-Qassam both pivoted

toward offering constructive advice for Syria’s ‘mujahideen,’

including how to face the challenges posed by the emerging triumvirate

of Turkey, Iran, and Russia, as well as by emphasizing the

strategic importance of fighting an underground guerrilla war as

the next stage in Syrian jihad.54 As al-Qassam wrote in June 2017,

external pressure on the Syrian jihad was so significant that the

ongoing fitna between HTS and al-Qa`ida needed to end. Notwithstanding

various accusations made, most al-Qa`ida figures who had

spoken on the subject—including al-Zawahiri—had focused and

continued to focus on prioritizing “unity” and “cooperation.”55

The one key and consistent exception to that rule was the diehard

al-Qa`ida loyalist Abu Julaybib who, since his resignation

from HTS in August 2016, had been driving tensions on the ground

by undermining al-Julani’s authority and repeatedly pitching the

formation of a new, al-Qa`ida loyalist faction to rival HTS.56 According

to three well-connected sources, Abu Julaybib had also

repeatedly tried to move back to southern Syria to pursue this separate

goal with the aim of coordinating the transfer of al-Qa`ida

loyalists from the south to Idlib to stand in opposition to HTS and

al-Julani.57 Abu Julaybib was a serious thorn in al-Julani’s side.

By the summer of 2017, another increasingly difficult issue

was HTS’ relationship with Ahrar al-Sham, once Jabhat al-Nusra’s

closest military ally but now increasingly distant from HTS.

Though Ahrar had always held politically and ideologically different

positions to Jabhat al-Nusra, evolving geopolitical dynamics,

the increasingly assertive role of Turkey, and Jabhat al-Nusra’s own

evolution all had a part to play in encouraging Ahrar’s own identity

rebrand, which eventually included an embrace of the green FSA

revolutionary flag and increasingly nationalist-focused rhetoric.58

The repeated breakdown of merger talks; Ahrar al-Sham’s role

in Euphrates Shield, close relations to Turkey, and support for Astana;

and the actual intra-rebel hostilities that preceded HTS’ formation

all prepared the ground for the most significant battle to take

place between the two groups. Between July 18 and July 24, 2017,

HTS launched a series of coordinated assaults on Ahrar’s network

of headquarters across Idlib, western Aleppo, and northern Hama.

What followed was a limp response by Ahrar’s fighters, who suffered

catastrophic defeat in a week.59

The fighting’s death toll, though, was very low—two or three dozen

from both groups combined, according to commanders from

both groups speaking to this author.60 Rather than fight back in

force, Ahrar personnel largely retreated, withdrew, or surrendered,

in part due to their long history of cooperation with Jabhat al-Nusra;

the localism that defined much of the two group’s micro-level

relations; and the shock and awe nature of HTS’ campaign. There

was also a question of poor resolve within Ahrar’s ranks. The group’s

especially broad spectrum of political and religious/ideological

thought had gradually eroded a shared sense of internal identity,

putting it at a significant disadvantage when faced with a more

ideologically unified adversary.

Aware that some fighters within its own ranks might balk at

fighting against fellow Islamist rebels, HTS had prepared its fighters

to turn on their long-time partners. For weeks beforehand, “Julani

dispatched his most important [Sharia figures] to talk to the

fighters,” one Islamist figure close to HTS’ Shura Council claimed,

“first to question the purity of Ahrar al-Sham’s political positions

and to suggest it had become a foreign puppet that would be used

to attack the mujahideen, and then to explain why it had become a

legitimate target.”61

By late July 2017, HTS had cemented itself as the dominant

armed actor in opposition-held areas of northwestern Syria. Its

main rival, Ahrar al-Sham, retreated back to its bases, hoping to

fight another day. Three months later, Ahrar elected an entirely new

leadership headed up by Hassan Soufan, a long-time former regime

prisoner who, as he told this author in person in October 2017, came

into the job determined to distinguish his movement from “criminal”

and “corrupt” projects, such as “Hitish and Daesh.”62

The Break Becomes Official

In a speech released on October 4, 2017, al-Zawahiri publicly admonished

HTS—again, without referencing the group by name—by

chastising those who try to “escape from facing reality and seek to

repeat the same failed experiment … [of trying to] deceive America,”

a reference to the argument that by breaking ties to al-Qa`ida,

jihadis could protect themselves from counterterrorism scrutiny.

Al-Zawahiri then went on to censure those who find false, legalistic

excuses to avoid or to dissolve one’s bay`a—an oath which he

describes as “binding,” any “violation” of which is strictly “forbidden.”

63 Five days later, a new jihadi group called Ansar al-Furqan

announced itself in Idlib as a movement that would remain loyal to

Islam where others were becoming “distant.”

[Ansar al-Furqan] are Sunni jihadist Muslims, consisting of [foreign

fighters] and [local fighters] who have attended most of the

Syrian events since their beginning and witnessed most of what has

become of the groups. Thus, they have discovered that the secret of

the issue and the reason behind deficiencies was the [new distance]

from the evident verses [of the Qur’an] and not adhering to them or

abiding by them and using the brain superficially and not giving

in to following the [Qur’an] in many issues.64

Multiple informed sources65 assured this author at the time that

Ansar al-Furqan was Abu Julaybib’s initiative and had gathered no

more than 300 al-Qa`ida loyalists in northwestern Syria. Several

days after Ansar al-Furqan’s emergence, HTS launched a low-level

security campaign across Idlib in which suspected al-Qa`ida loyalists

with positions critical of HTS were questioned by the group’s

internal security service. In a few cases, questioning led to detention,

but most were released.66

This attempt to reassert HTS authority and to intimidate potential

competition, paired with leaked comments by Atoun criticizing

al-Zawahiri’s October 4 speech, sparked fury within al-Qa`ida

circles.j Beginning on October 15, 2017, and ending six days later,

al-Oraydi published five “testimonies” in which he laid out al-Qa-

`ida’s various protests against the Jabhat al-Nusra-JFS rebrand and then HTS’ formation, which he explained had resulted in a

full break from al-Qa`ida. Al-Oraydi repeatedly labeled al-Julani’s

actions as acts of “rebellion”—similar to those of the Islamic State,

while explaining that al-Julani and Atoun had sold the JFS rebrand

to its early opponents as a move that would have had more of an

effect in the media than in reality. In other words, it had been suggested

that JFS would quietly retain its al-Qa`ida ties, presumably

given the presence inside Syria of senior al-Qa`ida figures like Abu

al-Khayr. Even this, al-Oraydi insisted, had proven to be deception,

as had al-Julani and Atoun’s repeated promise to abide by any future

decision by al-Zawahiri to reject the rebrand.

Predictably, al-Oraydi’s powerful critiques drew a strong response

from Atoun, who defended the methods and logic behind the

rebrand to JFS, while stretching the truth by describing the move

as something overwhelmingly supported within Jabhat al-Nusra’s

Shura Council and al-Qa`ida’s central circles. Atoun’s excuse for

refusing to reverse the JFS rebrand was to claim that al-Zawahiri

had been misinformed about its nature and that senior al-Qa`ida

figures like Abu al-Khayr and Abuj al-Faraj had consistently been

on al-Julani’s side. Conveniently, both were now dead and unable to

confirm Atoun’s claim, which has not been supported by any other

source before or since. Atoun also claimed that communications

with al-Zawahiri had been nonexistent for security reasons for nearly

three years (from November 2013 to September 2016)67—something

rejected by a senior al-Qa`ida “external communications”

official known as Abu Abdullah, who claimed in response that it

had long been possible to send messages to al-Zawahiri through one

of his colleagues, “almost on a daily basis.”68 In an apparent recognition

of al-Oraydi’s declaration that HTS’ creation represented a

full break from al-Qa`ida, Atoun suggested that although this had

not been the intention, JFS’ achievement of a broad merger (i.e.,

HTS) had met the necessary conditions to separate from external

ties of allegiance.

This tit-for-tat series of testimonies continued through late October

and into November 2017. Al-Qassam jumped to al-Oraydi’s

defense, and senior HTS figure Abu al-Harith al-Masri publicly

criticized al-Zawahiri, saying he was so distant from Syria’s realities

he had ceded his position of authority. Later in November, HTS

fighters arrested Abu Julaybib and his family at a checkpoint in

western Aleppo as they reportedly sought to escape Idlib toward

southern Syria. Hours later, al-Julani dispatched security units to

arrest al-Oraydi and several other al-Qa`ida loyalists—including

a member of al-Qa`ida’s central Shura Council, Abu Abdul Karim

al-Khorasani, and a close aide to al-Qassam known as Abu Khallad—

in a move later justified as preventing further “harm and evil”

espoused by those who advocated takfir (excommunication) upon

HTS and its leaders.69

HTS’ arrest of prominent al-Qa`ida figures drew ire both

amongst its own members and the al-Qa`ida loyalist community

inside and outside of Syria. Demands flooded in for the prisoners

to be released. Within that tense environment, al-Qa`ida-linked

calls for a loyalist mobilization in northwestern Syria also became

public. In his condemnation of the arrests, for example, Abu Hammam

al-Shami explained how an effort was underway to collect and

organize personnel.70 Upon his release from HTS detention, Abu

Julaybib immediately re-pledged his bay`a to al-Qa`ida and defiantly

asserted that “if you think by jailing us the idea of Al-Qaeda is

over, then you are delusional.”71

Clearly, neither side planned to back down, and whatever account

of events held more truth, the consequence was clear: HTS had severed itself and/or been severed from al-Qa`ida. With his

loyalists in HTS prisons, al-Zawahiri released another message on

November 28, 2017, in which he directly denounced HTS’ “violation

of the covenant,” accusing al-Julani of creating more unnecessary

complexity as well as “killing, fighting, accusations, fatwas and

counter-fatwas.”

We gave opportunity after opportunity and deadline after deadline

for more than a year, but all we saw was increasing aggravation,

inflammation and disputes … Verily, the jihad in al-Sham is a jihad

of the entire Ummah; it is not a jihad of the people of Syria; and it is

not a jihad of the people of Idlib, or Deraa or Damascus … The bay’at

between us … is a binding contract which prohibits [you] from being

able to breach it … I remind my brothers in al-Sham, that the

al-Qaeda organization repeated many times that it is willing to give

up its organizational ties with Jabhat al-Nusra if two matters were

achieved: the first is a union of the mujahideen in al-Sham; and the

second matter is an Islamic government is established in al-Sham,

and the people of al-Sham choose an Imam, and then at that time

and that time only – and not before then – we give up our organizational

ties and we would congratulate our people in al-Sham for

what they achieved … As for the creation of new entities without unity,

in which absurd schisms are repeated … this is what we refused.72

Al-Zawahiri’s interjection was a watershed moment, making

clear to the wider global jihadi movement that a real split had taken

place between al-Qa`ida and its Syrian affiliate. That clarified

break has not appeared to benefit al-Julani, however, as his broader

position in northwestern Syria looks to have become more precarious.

Having sought out negotiations with Ankara in October 2017

to ensure a Turkish incursion into Idlib was done without the threat

of violence by Turkish forces against his group (and the resulting

threat of a broader anti-HTS front emerging), al-Julani has since invited FSA groups in Idlib to consider a merger “for the sake of defending

Syria’s revolution.”73 Sending such an “invitation” to groups

that did not share his hardline Islamist ideology would have been

considered outrageous by al-Julani a year prior, but its use in early

2018 spoke volumes about his sense of being surrounded by hostile

actors. That would also explain HTS’ repeated military withdrawals

along the periphery of Idlib’s core central, more defensible areas,

and online discussion of strategically shifting to guerrilla tactics.74

Notwithstanding a determined mediation effort that lasted

through December 2017 into early January 2018, which resulted

in a short-lived agreement to coexist in peace, the relationship between

HTS and al-Qa`ida loyalists in northwestern Syria remains

tense. The two remain decidedly separate, as officially established

by al-Qa`ida’s January 7, 2018, statement quoted at the beginning

of this article. For reasons of Islamist brotherhood and the prohibition

of shedding blood, as well as continued, shared, long-term

objectives, it is very unlikely both sides will fall into a state of all-out

conflict. However, were HTS to successfully position itself as an actor

tolerated by some regional and international players in at least

part of Idlib, al-Julani’s willingness to allow a faction of committed

global jihadis with overt allegiance to al-Qa`ida may become an

overly inconvenient fact needing to be dealt with. Unless that happens,

however, the two movements are likely to continue existing

uncomfortably together in Idlib.

That produces a complex counterterrorism threat, in which a

locally focused jihadi outfit with a sizable 12,000 fighters continues

to control territory, govern people, and maintain sources of local

finance, while accepting—even grudgingly—a deeply dangerous,

small, tight-knit clique of al-Qa`ida terrorists committed to attacking

the West. That image looks eerily similar to the Taliban-al-Qa-

`ida relationship in Afghanistan in 2000-2001, the consequences

of which are well known to all. HTS may not be al-Qa`ida anymore,

but that does not make its existence any less dangerous.

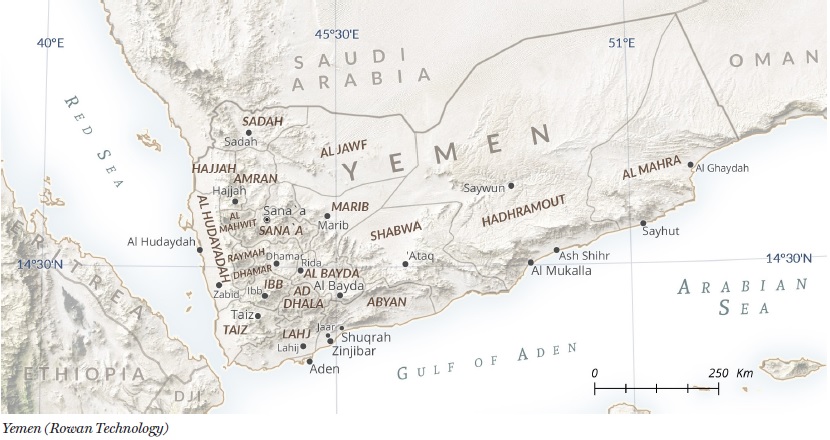

Can the UAE and its Security Forces Avoid a Wrong Turn in Yemen?

The complex war in Yemen and the ensuing collapse of a

unified Yemeni government has provided al-Qa`ida in the

Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) with opportunities to develop

and test new strategies and tactics. While AQAP has been

weakened by Emirati-led efforts in southern Yemen and

recent U.S. strikes, it remains a formidable foe whose more

subtle approach to insurgent warfare will pay dividends if

there is a failure to restore predictable levels of security,

sound governance, and lawful policing in the country. Three years of war in Yemen have laid waste to the country’s

infrastructure, killed at least 10,000 people, impoverished

millions, and empowered insurgent groups

like al-Qa`ida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).1 The

war, or more accurately wars, in Yemen are layered and

complex with a growing number of factions, all with their attendant

militias. Before the launch of “Operation Decisive Storm” by Saudi

Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and their allies in March

2015, Yemen was already a country riven with divisions.2 The internationally

recognized government—in exile in Saudi Arabia since

March 2015—of President Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi exercised

little control over Yemen. This was made clear when Yemen’s Zaidi

Shi`a Houthi rebels seized the capital of Sana’a in September 2014

with the acquiescence of parts of the Yemeni Army.3 In the south,

separatist movements calling for the recreation of an independent

south Yemen have gained influence and power.4 The increase in

factionalism and the hollowing out of an already weak national

government has provided AQAP with an abundance of new opportunities

to grow its organization and its influence. Opportunities

that it has, over the last three years, exploited with notable success.

In April 2016, Yemeni troops—nominally allied with the Hadi

government—backed by Emirati units retook the port city of Mukalla,

which AQAP had held and governed for the previous year.

Despite initial claims by the Saudi and Emirati coalition, the retaking

of Mukalla was largely bloodless.5 AQAP chose a strategic

retreat rather than to fight a superior force. As it has done in the

past, AQAP sought and found shelter in Yemen’s vast hinterlands.6 Since retaking Mukalla, Emirati-backed forces such as the Hadrami

Elite Force and its Security Belt Forces have used Mukalla as a

central base for operations aimed at degrading AQAP.7 This ground

war is being aided by the United States, namely through the use of

UAVs that have successfully targeted a number of AQAP’s leaders.8

While there is some evidence that AQAP has been weakened by the

ground campaign and the targeting of its operatives by UAVs, as it

has demonstrated in the past, it is resilient, adaptive, and—most

critically—expert at exploiting local and even national grievances.

AQAP is not the organization it was three or even two years ago.

Just like most of Yemen’s political, social, and insurgent groups, it

has been changed by the country’s multifaceted conflict. AQAP’s

focus has shifted from the “far enemy”—though, this is not to say it

does not continue to pose a threat to the West—to an array of “near

enemies.”9 Its concerns, both political and martial, are local and

national rather than international. Its de-prioritization of ideology

reflects this shift. In many respects, AQAP has adopted and is

guided by a more subtle and indigenized strategy with two primary

aims: organizational survival and long-term growth. To achieve

these aims, it remains intent on building alliances where it can by

leveraging its fighting capabilities and by exploiting local and national

grievances.10

Emirati-led efforts to combat AQAP in southern Yemen—largely

limited to the governorates of the Hadramawt and Shabwa—could

succeed where others have failed, or they could result in an abundance

of new opportunities for AQAP to exploit. The Emirati-led effort

to combat AQAP is another test for counterinsurgency warfare.

While the Emiratis and the security forces that they are backing are

making gains against AQAP in some parts of southern Yemen, these

could be compromised by missteps that allow AQAP to apply the

lessons that it has learned over the last three years.

Overcoming the Friction of Factions

The idea of friction in war was first introduced by Carl von Clausewitz

in his book, On War. Clausewitz describes friction as a force

that arises from the many unpredictable variables that materialize

during war that can lay waste to the best-planned campaigns and

the most efficient military forces.11 It is friction that distinguishes

real war from war on paper.12 There are few theaters of war that are

as capable of generating as much friction as a war in Yemen. As is

evidenced by Yemen’s history, the country, its people, and its terrain

are not kind to outside powers.

In 25 BC, a Roman expeditionary force led by Aelius Gallus was

forced to retreat from what is now the governorate of Marib. The

Ottoman Turks tried to subdue Yemen twice and failed both times

despite expending vast sums of blood and treasure on the effort.

Most recently, from 1962 to 1967, Egypt, under President Nasser,

intervened in what was then north Yemen on the side of Republican

forces who were fighting the Royalist supporters of Imam

Muhammad al-Badr. Despite deploying more than 70,000 soldiers who enjoyed extensive air support, the Egyptian campaign in

north Yemen failed.13 The Egyptians lost at least 10,000 soldiers.14

Their rivals, the Royalists, were armed with light weapons and had

no air support. However, they leveraged Yemen’s rugged terrain,

superior human intelligence, and, most critically, the factionalism

that predominated in much of Yemen. Egyptian officers often complained

about their “allies” who fought with them during the day

and against them at night. These shifting alliances were reflective

of the pragmatic and often quite democratic nature of the plurality

of tribal relationships, structures, and allegiances that predominate

in much of Yemen.

A counterinsurgent war in Yemen—which is what the Egyptians

were fighting from 1962 to 1967—is replete with challenges

for counterinsurgent forces and abounds with opportunities for the

insurgent. This was the case before the collapse of the central Yemeni

state and fragmentation of the Yemeni Army in 2014. Now that

the country has largely been divided into a multiplicity of fiefdoms

governed to varying degrees by numerous factions and militias, the

challenges for conducting counterinsurgent warfare are even more

pronounced.

Chief among these challenges is the factionalism that predominates

across almost all of Yemen. In the south, where Emirati-

backed forces are primarily conducting their campaign, there

are multiple insurgencies underway. Various southern separatist

groups are fighting to recreate an independent south Yemen, salafi

militias are fighting to advance their own conservative religious

agendas, displaced elites are fighting to retain and/or recover their

power and influence, and both AQAP and, to a far lesser degree,

the Islamic State are active across southern Yemen.15 These factions

and their competing agendas produce high levels of Clausewitzian

friction for the Emiratis and the security forces that they are supporting.

To combat factionalism, the Emiratis have tried to forge three security forces: the Security Belt Forces (also referred to as al-Hizam

Brigades) largely deployed in southwest Yemen; the Hadrami

Elite Forces deployed in the governorate of the Hadramawt; and

the Shabwani Elite Forces deployed to southern Shabwa.16 a The

three forces are primarily composed of Yemeni soldiers drawn from

the southern governorates. These soldiers often have Emirati and

foreign advisors. In the case of the Hadrami Elite Forces, the men

are almost all from the Hadramawt, the rationale being that this

incorporation of men drawn from the areas they will be deployed

to will enhance the forces’ HUMINT capability while at the same

time ensure some local support.17 The leadership of the three forces

is largely drawn from tribal elites, some of whom formerly served as

officers in the Yemeni Army, and ranking members of al-Hirak (the

Southern Movement).18

The mission of the Emirati-backed forces—at least in theory—is

twofold: first, restore a measure of security in those cities under

their control, namely Aden and Mukalla, and the areas around

them. Second, plan and launch security sweeps and clearing operations

aimed at combating AQAP and what is left of the Islamic

State. By using Mukalla in particular as a key staging point, the

sweeps and clearing operations are designed to gradually widen

the area controlled by the Emirati-backed forces.19 Following the

ink spot theory, Mukalla and Aden will be held and secured as the

security forces move into and clear the surrounding areas—many

of which have been dominated by AQAP for the last three years.20

Due to the topography north of Mukalla—which is riven with deep wadis, box canyons, caves, and mountains—the ink spot looks more

like an ink blot as security forces struggle to clear and hold broken

terrain that is ideal for ambushes and raids. Hadrami Elite Forces

have repeatedly been targeted in the southern reaches of the Hadramawt.

21 There, the roads are few and almost always overlooked by

high ground. AQAP has engaged in numerous hit-and-run attacks

on the elite forces.22

Despite the treacherous terrain, the Hadrami Elite Forces have

made some progress in clearing AQAP from the southern half

of Wadi Huwayrah, Wadi Hajr, and the areas surrounding Ash

Shihr.23 However, these gains are frequently reversed due to poor

coordination between individual units within the security forces,

which—as has often been the case with the Yemeni Army—do not

adhere to chains of command. This lack of coordination is especially

pronounced between the largely independent Security Belt Forces,

Shabwani Elite Forces, and the Hadrami Elite Forces. The three

forces do not have a unified chain of command and their commanders

are often at cross-purposes.24

While the Emirati effort in southern Yemen is currently benefiting

from the surge in southern nationalism, this nationalism

is itself factional and subject to intense internal fighting. In the

Hadramawt, groups calling for the independence of the governorate—

which has a history of self-governance—have been active for

years.25 Many who serve within the Hadrami Elite Forces are more

dedicated to an independent Hadramawt than to other iterations

of an independent south Yemen. Those who serve in the Security

Belt Forces differ from those serving—especially at the command

level—in the Hadrami Elite Forces in that most either support or

are fighting for a wholly independent and unified south Yemen

along the lines of the former People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen

(PDRY). In addition to groups that are either advocating or

fighting for different visions of an independent south Yemen, there

are elites who have been displaced by those who have been more

successful at cultivating their relationship with the United Arab

Emirates. They, too, will fight to recover what they feel they have

lost in terms of influence, wealth, and power.26

There is a lot at stake in south Yemen. It is home to most of the

country’s natural resources, and its most important oil handling

facilities are located there. The creation of a new country or, at a

minimum, new autonomous regions such as the Hadramawt is possible.

Such high stakes all militate against the formation of cohesive

security forces capable of engaging in the kind of sustained operations

that counterinsurgency warfare demands. Adding to what is

a long list of circumstances that will produce high-levels of friction

is AQAP’s subtle approach to achieving its aims.

A More Subtle Foe

AQAP is intently focused on fighting what it views as a long war

for the hearts and minds of the people it seeks to govern. As with

any organization, there are those who believe the rhetoric produced

by the leadership and those who—usually the leadership itself—

recognize the rhetoric as an expedient reference point—possibly

another political tool—rather than as a binding ideology. While

AQAP’s leadership and media wing continue to produce (though

media releases have decreased) the kind of extremist religious propaganda

that jihadi groups have become known for, this is not necessarily

reflective of the strategy and tactics employed by AQAP on

the ground. This has been the case for much of the last three years.

AQAP’s April 2015 takeover of Mukalla was a watershed moment

for the group. The takeover, which was largely bloodless, allowed

them to seize large amounts of cash, weapons, and materiel,

but most importantly, it provided the leadership with an opportunity

to try out new strategies and tactics.27 The last time AQAP

held and attempted to govern a significant swath of territory was

in 2011-2012 when it took over a large part of the governorate of

Abyan in the wake of the uprising against Yemeni president Ali

Abdullah Saleh.28 AQAP learned a great deal from its failures in

2011-2012. Namely, it learned that its radical interpretation of sharia

is not acceptable to a majority of Yemenis. It also learned that

the utilization of a punishment strategy is not suitable for a country

where many people identify with various tribes that are often wellarmed.

In 2011-2012, AQAP attempted and failed to impose its will

on those it wanted to govern by force.29 It did not make this mistake

in Mukalla in 2015.

Rather than relying on a punishment strategy when it took over

Mukalla in April 2015, AQAP adopted a far more subtle and pragmatic

strategy that combined ruling covertly through proxies with

a continued focus on guerrilla and hybrid operations against its

rivals outside the city. During its yearlong occupation of Mukalla,

AQAP largely refrained from imposing its interpretation of sharia.

Instead, it allied itself with select local elites and focused much of

its effort, with some success, on improving living conditions in the

city and providing predictable levels of security.30 AQAP’s efforts to

improve living conditions, operate charities, and provide security

during its occupation of Mukalla are now being contrasted with

current Emirati-led efforts to govern the city. The result, according

to some, is that AQAP did a better job.31 While this is to a large degree

subjective, it is reflective of a widespread sentiment.32 And it

is a view that will be used by AQAP’s leadership to critique the new

government in Mukalla.

AQAP’s strategic retreat from Mukalla in April 2016 also reflects

the fact that the leadership learned many lessons in 2011-2012. The

leadership had clearly planned and prepared for the retreat. They

had no intention of taking on a superior force aided by air support.33

This was a mistake they made in trying to defend and hold parts of

Abyan in 2012. AQAP’s leadership recognized that preserving what

they viewed as good relations with the people of Mukalla and the

alliances they made with some members of the Hadrami elite was

critical to their ability to continue fighting.

Since its strategic retreat from Mukalla, AQAP has continued to

pursue its more subtle strategy and has successfully enmeshed its

operatives—both covertly and overtly—within many of the militias,

both salafi and tribal, that are fighting the Houthis, their allies, and

in some cases Emirati-backed forces.34 AQAP remains one of the

best organized and motivated insurgent forces in Yemen, and this

has allowed it to build relationships with numerous militias.35 Most

of these relationships will not abide and are merely based on the

fact that AQAP and the militias share a common enemy, whether

that be the Houthis or the Emirati-backed forces.36 For AQAP,

the fact that the relationships and alliances are only nominal is of

little consequence. What is important is that enmeshment within

anti-Houthi forces allows for concealment, a chance to demonstrate

their superior fighting abilities, and, in some cases, income

for AQAP. In some areas, just as it has in the past, AQAP acts as a

mercenary force for elites whose interests happen to align with its

own, even if this alignment is only temporary.37

AQAP’s focus on enmeshment, covert governance where possible,

and jettisoning of a punishment strategy will make it more difficult to combat. This, combined with the fact that Yemen is mired

in multiple wars being fought by multiple insurgent groups, means

that discerning who is and who is not a member or ally of AQAP

will be all the more difficult. Yet, AQAP’s adoption of a more subtle

strategy makes discernment, security, and good governance all the

more important.

Challenges and Opportunities

While the Emirati-led effort to combat AQAP is heavily reliant on

indigenous fighters, the country’s efforts have led to the perception

that the UAE is a colonizing force. The growing influence of the

UAE and those elites that it has either chosen to empower or that

have sided with it are already fueling debate and rhetoric on all sides

of the conflict. While the UAE has been careful to minimize the

outward signs of the presence of its forces and advisors in southern

Yemen, there is the growing sense among many Yemenis that the

Emiratis are in southern Yemen to stay.38 Stories about the UAE’s

occupation of the Yemeni island of Socotra and its plans to build

a military base there have provoked angry responses from many

sectors of Yemeni society.39 AQAP will be quick to take advantage

of and foster the perception that the UAE is intent on occupying

Yemen for its own purposes. The veracity of the claim matters little.

While Muslim and Arab, the Emiratis, which also employ many

foreigners as advisers and mercenaries, are foreigners, and few actions

empower an insurgency like foreign occupation—perceived

or otherwise.40

Concurrent with what could be a growing perception by many of

the UAE as an occupying force in Yemen is the problematic tactics

used by some of the UAE-backed security forces. These security

forces are conducting sweeps that often result in the detention of

large numbers of men with no or only a minimal relationship with

AQAP.41 AQAP controlled Mukalla and many of the surrounding areas

for more than a year. Many residents in these areas were forced

to interact with AQAP on some level. At the same time, AQAP recruited

many men as foot soldiers. For the most part, these recruits

did not share the group’s ideology or aims. Most joined to collect

salaries, receive food aid, and, in some cases, protect their families

from retribution by AQAP. Still others—a minority—joined to help

AQAP fight the Islamic State whose ideology and tactics are viewed

by most as far more virulent and alien to Yemen.42 There is also the

very real danger that, as happened in Afghanistan in the early years

of the U.S. war there, informants label rivals as AQAP for security

forces as a way of settling scores, making money, removing rivals,

and enhancing their own power.43 Given the prevalence of factions

and competing agendas in Yemen as well the informal nature of

many of the security units, the danger of this is especially high.

In addition to the possibility that many of those rounded up in

the sweeps are not members of AQAP, there are credible allegations

of security forces abusing detainees. In June 2017, Human Rights

Watch released a report that cited numerous cases of torture, abuse,

unlawful detention, and disappearances purportedly carried out by

Security Belt and Hadrami Elite forces.44 Additional reports have

appeared in the international media about Emirati-run detention

centers where Yemenis held for alleged ties to AQAP have been

tortured, including reports that some detainees were roasted on a

spit.45 Reports of these kinds of actions—regardless of whether or not they are true—will be seized upon by AQAP. It is worth remembering

that the first issue of AQAP’s English language publication,

Inspire, featured an article written by Usama bin Ladin in which

he referenced the abuses committed at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq

as evidence of the United States’ malicious intent.46 Similarly, the

alleged abuses committed at Emirati-run detention facilities will

fuel resentment that AQAP will exploit.

AQAP and other insurgent groups operating in Yemen will seize

on any and all missteps by the Emirati-backed forces and the Emiratis

themselves. Having largely abandoned the punishment strategy

in favor of one that is better adapted to the socio-cultural terrain

it operates in, AQAP’s leadership likely understands the benefit of

drawing the UAE and its forces into a war where they employ a

punishment strategy of their own. Such a strategy, especially when

employed by a foreign power, will alienate the populace and in turn

drive recruitment for AQAP and other groups.

Conclusion

In his article, “Evolution of a Revolt,” T.E. Lawrence, speaking

about the Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire in 1916-1918,

argued that insurgents would be victorious if they understood and

applied certain “algebraical factors.” These factors included mobility,

force security, time, and respect for the populace.47 AQAP has

adopted and is, to varying degrees, employing Lawrence’s algebra

for a successful insurgency. It has retained its mobility. Its enmeshment

within anti-Houthi forces is—to some extent—contributing to

force security and drawing its enemies into a punishment strategy.

AQAP is also patient and committed to the long war and is intent

on working within the Yemeni socio-cultural context in a way that

allows subjects to remain, at a minimum, neutral. This is not to say

that AQAP will be victorious. However, its ability to adapt, learn,

and employ strategies that are increasingly well adapted to the areas

in which it operates, does mean that it will survive and will, given

the opportunity, go on the offensive yet again.

As Colonel Gian Gentile argues in his book Wrong Turn: America’s

Deadly Embrace of Counterinsurgency, “hearts-and-minds

counterinsurgency carried out by an occupying power in a foreign

land doesn’t work, unless it is a multigenerational effort.”48 While

the Emiratis do not seem intent on occupation and its counterinsurgency

efforts are heavily reliant on Yemenis, it is a foreign-led

effort in a country that has, throughout its history, violently and

successfully resisted incursions by outside powers. While it is extremely

unlikely that AQAP could ever take over southern Yemen,

short of the kind of highly problematic, multigenerational effort

described by Gentile, it will remain a persistent and potent threat

over the long term.

The short-term success of Emirati-led efforts in Yemen are predicated

on their ability to compete with AQAP in regard to the levels

of security and efficacy of governance that they can provide. This

success is also predicated on the Emiratis’ ability to avoid being

seen as occupiers acting through militias motivated by their own

factional interests. A failure to restore governance, predictable levels

of security, and “clean” policing will be exploited by an enemy

that—while weakened—remains capable, resilient, and perhaps

most importantly, patient.

Letters from Home: Hezbollah Mothers and the Culture of Martyrdom

Hezbollah’s culture of martyrdom has helped sustain the

organization’s manpower needs since the organization’s

founding. A critical question, however, is how the group

communicates this narrative to its base, especially given

recent challenges to the group’s legitimacy as a result of

its intervention in Syria. The ‘Party of God’s’ online content

reveals that it does so in part by using the mothers of

martyred fighters to promote the culture of martyrdom.

Mothers possess unique access in society due to their ability

to shape the minds of the next generation. As a result,

Hezbollah uses their voices to amplify its propaganda in a

way that resonates with the group’s following. Signs of tension

between the party and these women, however, could

pose challenges to this strategy in the future.

In March 2017, an article on Hezbollah’s online media outlet

Arabipress featured a poem by the Egyptian poet Hafez

Ibrahim (b. 1872) that opens with the line, “Our mothers

are like our schools; pampering them means securing our

future.”1 Seven months earlier, the same website posted a

music video in which a young man crooned, “For you, my mother,”

sentimentally dramatizing their close relationship and her reaction

to his eventual martyrdom.2 Frequently, Hezbollah’s media also

quotes a song by the renowned Lebanese musician Marcel Khalife

to honor the mothers of its martyrs: “ajmal al omahat” (the most

beautiful mother).3 These items are not simply rhetorical devices;

they also serve a strategic purpose. Hezbollah uses the mothers of

its fallen fighters to sustain a culture of martyrdom that provides it

with a self-replenishing pool of fighters, a critical function throughout

the group’s history but especially today.

Since late 2012, Hezbollah’s founding principle of resistance

to Israel has been eclipsed by its intervention in Syria on behalf

of the regime of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad. Mounting casualties

and increasing resentment4 among the group’s base in

Lebanon have, to some extent, challenged the pervasive culture of

martyrdom that sustains its manpower. This is where the mothers

of martyrs come in. In order to retain control over the martyrdom narrative, Hezbollah uses these mothers to relay stories that promote

both self-sacrifice and the sacrificing of one’s children to the

resistance. As the opening examples illustrate, the cooptation of

popular refrains are meant to capitalize on a deeply held local value:

the importance of mothers in building a society. Mothers, therefore,

represent a crucial demographic for Hezbollah, serving as a bridge

between the party leadership and the community from which it

draws its fighters. In order to convince these women to sacrifice

their sons, the party shrewdly uses the voices of those who have already

done so. Signs of tension between the group and the mothers

of its martyrs, however, could call into question the viability of this

strategy in the long term.

The Culture of Martyrdom

Throughout the first three decades of Hezbollah’s existence, its role

in the “axis of resistance” against Israel imbued it with legitimacy,

attracting ideologically motivated fighters to its cause. Equally important

in this respect, however, was the group’s culture of self-sacrifice

that regarded martyrdom as a blessing. Whereas the resistance