In Gaza, over 100,000 tonnes of explosives have been dropped on the small 41-kilometre-long coastal enclave that was already under a brutal 18-year blockade, and more than 650 days of a relentless onslaught have pulverised homes, lives, and the threads of memory.

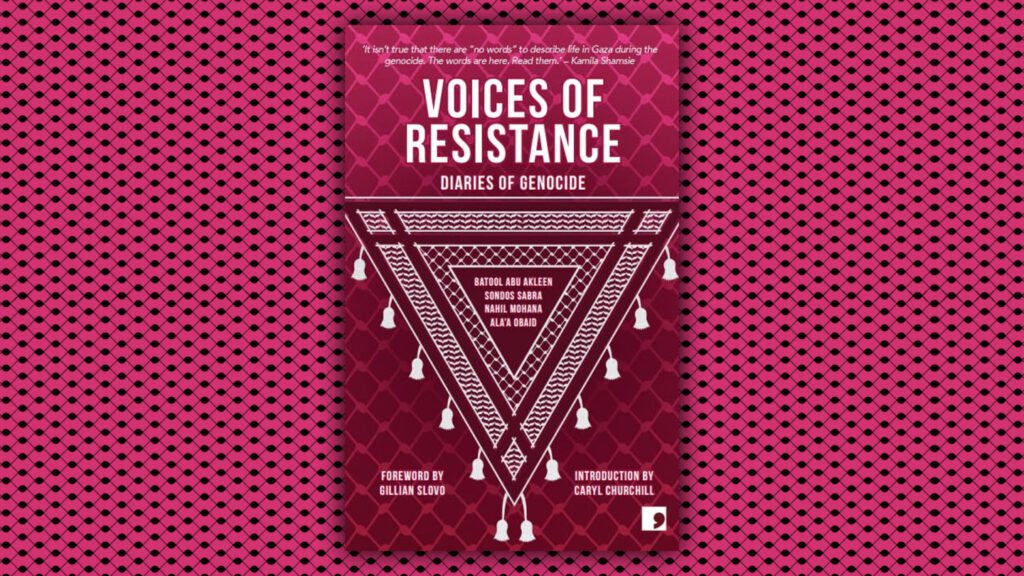

In this crucible of loss, where survival is a daily rebellion, Batool Abu Akleen, Sondos Sabra, Nahil Mohana, and Ala’a Obaid refuse to let their voices be silenced — Voices of Resistance: Diaries of Genocide (Comma Press, July 2025) is their testament.

Scrawled in the chaos of tents, shattered shelters, and faltering phone screens. These diarists — from poets, translators, novelists, and mothers — span generations and experiences, documenting Gaza’s anguish and resilience amid Israel’s brutal genocide and siege.

Batool, a 20-year-old poet, read Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl mere days before October 7 — an eerie prelude to her own suffering.

Like Frank, who chronicled her life in Nazi-occupied Amsterdam, Batool, Sondos, Nahil, and Ala’a weave personal struggles with the trauma of a persecuted people. Yet, the differences are stark. Frank’s diary was published posthumously. It is a monument to a tragedy concluded, viewed through history’s protective distance. Voices of Resistance, however, is a living document.

Written and published amidst Israel’s ongoing genocide in Gaza, its pages pulse with an urgency. This makes the book an act of survival and a refusal to be silenced in a world that often averts its gaze.

‘Thank God we are still alive’

The artistry and creativity displayed by these four remarkable women both astonish and humble readers. Detailing their lives amidst unimaginable dangers, their narrations boast powerful storytelling, poetic flourishes, and poignant homages to literary greats.

“Does it seem ridiculous to say your diary entries are enjoyable?” Caryl Churchill asks in her introduction, capturing the paradox of finding beauty in narratives of horror.

Sondos Sabra’s diaries are a delicate archive of a homeland unravelling, a careful preservation of what might be lost. Memories of olive harvests, an annual ritual for Palestinians that symbolises an unbreakable connection to the land, are now tainted by war’s acrid smoke.

After an eight-month silence, Sondos admits that her thoughts “appear in half-formed sentences, splintered by the overwhelming things I’ve seen and experienced.”

Sondos’s internal fracturing is mirrored externally. Her entries are often adorned with poetic titles, but starkly shift to mere dates in moments of heightened tensions. The absence of titles marks the peak of danger, and subtly turns the dairy’s very format into a barometer of unfolding tragedy.

Their return hints at a fleeting respite, a quiet signal that Sondos has survived the latest onslaught. Nahil Mohana, a single mother, echoes these shifting rhythms of endurance.

Her recurring affirmation, “Thank God we are still alive. Thank God for the blessing of a new day,” after intense bombings. A prayer professing gratitude under duress stirs readers with its quiet strength.

Building on this sensory assault, Nahil details how Gazans have developed an extensive vocabulary for “the noises of war.”

“Aerial bombing, bouf. Naval bombing, tsooo. Artillery shelling, dddof. Drones, trak trak trak. Racing heartbeat, D-duf d-duf.”

She articulates how constant attacks force an already overwhelmed people to internalise and categorise alien, violent noises through a chilling and precise lexicon.

Fragile like negotiations

Batool immerses readers in displacement’s immediacy. Her entries spanning nine days in a camp begin mid-crisis in a four-by-four meter tent she calls “aristocratic among the displaced.”

She details noisy mornings — salty wash-hut water. Phonetics lecture sped up to match her laptop’s teetering battery. And even the crumbling texture of her favourite ghorayeba biscuit, which is “fragile like negotiations,” a comparison she draws with herself, as it “melts in your mouth just like my toughness melts when I notice the buzzing of Israeli drones.”

This delightful but devastating metaphor equating crumbling cookies to the precariousness of peace talks and her feigned toughness reveals a mind that seeks meaning through language even as it fractures under pressure.

Batool’s section concludes with a ceasefire announcement, filling readers with an urge to shield her, knowing her fierce spirit will face the crushing reality of a truce that will not hold.

Batool’s honesty about the survival’s moral cost is startlingly candid. She admits to rejoicing in her own safety, even as others mourn, “abandoning my morals as the world has abandoned us”, offering a glimpse into the brutal reckoning demanded in such circumstances.

Nahil, on the other hand, finds solace in the communal spirit – market vendors defying famine, a wedding in a school.

Her diary entry describing the scenes of Gazans returning to their homes in the North after the Israeli forces withdrew from the Netzarim Corridor, aptly titled The Season of Returning from the North. She flips the script on Tayeb Salih’s classical novel, Season of Migration to the North. Salih’s work explores the fraught, often destructive pull of the global South toward the colonising North.

Nahil reclaims the idea of “return,” chronicling a homecoming to a devastated Gaza — an act of collective defiance. This return is a kaleidoscope of emotions, filled with both joyful, tearful reunions and, of course, the absence of others. She depicts the arrival of a woman, alone, whose husband and son were martyred in the South, and yet “she remains, she returns.”

Nahil asserts an unyielding, collective commitment to the homeland: “We have succeeded where Palestinians have failed since 1948… There will be no second Nakba.”

Batool’s inward battle with morality and Sondos’s outward embrace of communal strength demonstrate the varied and deeply human responses to genocide.

Ala’a Obaid, pregnant with her third child, writes with unflinching realism. She begins with a beautiful dedication to her newborn child, who “came into this world on Valentine’s Day 2024, in spite of this war.”

Her account of giving birth alone in a bathroom captures life’s persistence against death, genocide invading even the most intimate of moments.

Ala’a observes how nature, too, betrays Palestinians — the sea’s waves blend with an F-16’s roar, turning a source of solace into a conspirator with the mechanics of war.

Perhaps the most unsettling aspect of the book is how it provides a window into how Gazans adapt to circumstances that should never be normalised.

An Israeli gunboat near the shore where Ala’a’s children play no longer frightens her. Batool writes of women donning makeup and men carrying briefcases, “as if nothing has happened”.

In a shattering moment of self-introspection, she looks at the rings on her fingers and wipes the kohl from her eyes, wondering “if I, like them, have adapted”.

Ala’a’s account of people dodging bullets “like characters in a PUBG game” paints survival as an entertainment rigged for death. This ability of Gazans to endure – whether by daily rituals or desperate flight – reflects their remarkable strength.

But it is a piercing call for us, the readers, to challenge a reality that must never be accepted.

An act of remembrance

Voices of Resistance directly addresses the pointed lament in the final lines of Mahmoud Darwish’s prose poem Empty Boxes — an evocative image for the fragility of memory when a people’s narratives are absent.

“Luckily or unluckily for us, foreign historians, experts on our destinies and our oral history, were not here, so we don’t know what happened to us.”

Darwish’s critique of the external gaze and the fear of unrecorded or distorted accounts is precisely the void these women bravely fill. They are Gaza’s “local historians” chronicling their unfolding history.

Voices of Resistance is a profound act of remembrance as Sondos affirms, “I think, I write, and I remember. I remember that I remember, and I will not have that memory erased.”

The diaries represent a powerful response to the erasure Darwish warns of. Instead of cold numbers and abstract political jargon, these pages offer irrefutable proof of lives lived and spirits tired, but unbroken.

Batool, Sondos, Nahil, and Ala’a transform trauma’s “empty boxes” into vessels brimming with indomitable truth.