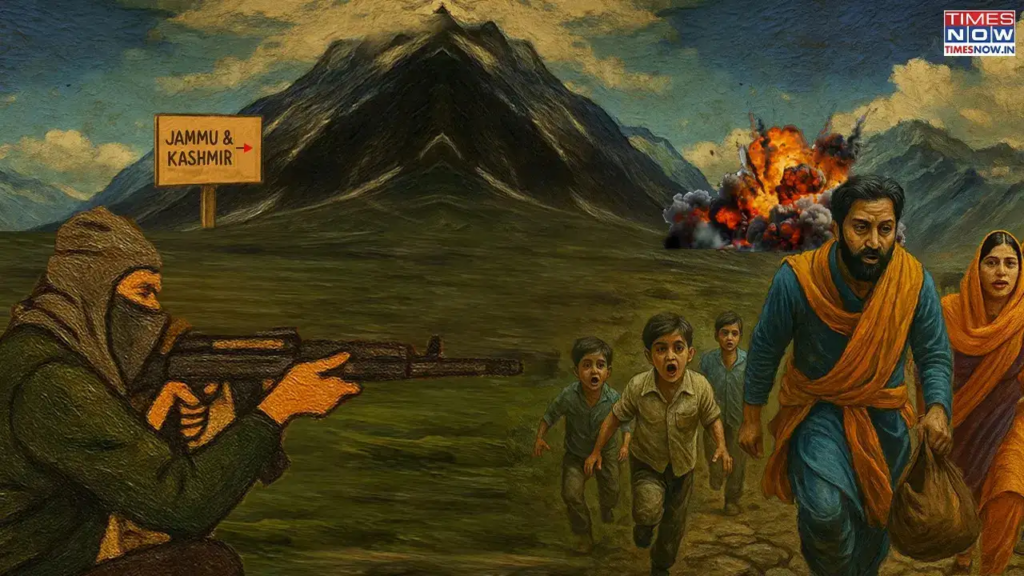

This weekend edit revisits the tragic 1990 exodus of Kashmiri Pandits, the political missteps that enabled it, and why, decades later, the community’s wounds remain unhealed. With a fresh terror attack in Pahalgam reopening old scars, it raises a pressing question: can Kashmir truly move forward without justice for those who were forced to flee their homeland?

“Agar firdaus bar roo-e zameen ast, Hameen ast-o hameen ast-o hameen ast. (If there is a heaven on earth, it’s here, it’s here..) These were the famous words used by the renowned poet Amir Khusro to describe the beauty of Kashmir. However, this majestic crown of India has witnessed significant violence since Independence, with the Kashmiri Pandits bearing a heavy cost. Once regarded as key stakeholders in the valley, the Pandits now associate this “heaven on earth” with sorrow and loss. Displaced from their ancestral homes and villages, many continue to live as refugees, carrying the burden of a painful past they would rather forget.

For the unversed, Pandits, who were always in the minority, contributing just 4 percent of the population, once held a significant influence over the affairs of the state, far exceeding their numbers. The Kashmiri Pandits owned around 30% of the land in the state between 1950 and 1976. This was prior to the land reform acts. The dominance of Pandits in a Muslim-dominated state was always a focal point of resistance. Kashmir, which was always prone to socio-economic and cultural discord, gradually shifted towards deep turbulence during the late 1980s with the rise of militancy in the valley. Pakistan, which by then had already lost two wars to India – one in 1947 and then in 1965 over the accession of J&K to the Indian Union, was always eying an opportunity to disrupt the peace and harmony in the valley.

It was the year 1990 when the social fabric of Kashmir changed forever with the departure of Kashmiri Pandits. But why was such a well-to-do community forced to flee their homes overnight? And, why is it still haunting India? Let’s delve into one of India’s biggest crises that we are yet to come to terms with.

In 1975, the Indira-Sheikh Accord was signed between Kashmiri politician Sheikh Abdullah and then Prime Minister of India Indira Gandhi, outlining that Kashmir would continue to be governed under Article 370 of the Constitution, which gave the state an autonomous status as a constituent of India. Abdullah became the chief minister of J&K with the support of Congress.

In 1977, the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) was formed by Amanullah Khan and Mohammad Maqbool Bhat with an aim to ‘liberate’ Kashmir from India and Pakistan. This would prove to be one of the key factors that would change the history of the valley forever.

The Tumultuous Turn in Kashmir: From Political Upheaval to Pandit Exodus

In 1982, the death of Sheikh Abdullah marked a transition in Jammu and Kashmir’s political leadership, with his son Farooq Abdullah assuming the role of Chief Minister. However, his tenure was short-lived. In 1984, a political coup orchestrated by the Indira Gandhi-led central government led to his dismissal. The then Governor Jagmohan Malhotra, acting on Delhi’s directives, replaced him with Ghulam Mohammad Shah, Farooq’s brother-in-law, who had defected from the National Conference. Shah formed a new government with Congress support at both the state and central levels.

That same year, the execution of Maqbool Bhat, the co-founder of the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF), sparked a wave of unrest. The move fuelled separatist sentiments, and Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) began backing militant groups like the JKLF with arms, training, and ideological indoctrination. As Kashmiri youth were radicalised, separatist violence surged.

In 1986, GM Shah’s decision to build a mosque at the site of an ancient Hindu temple in Jammu triggered mass protests. Around the same time, the Rajiv Gandhi government opened the Babri Masjid gates for Hindu worship, a move that had ripple effects across the region. Communal violence erupted, targeting Hindu homes, shops, and temples, especially in Anantnag, the constituency of Congress leader Mufti Mohammad Sayeed. In response, Governor Jagmohan dismissed Shah’s government, reinstating Farooq Abdullah as CM.

The ‘Rigged’ Election

The 1987 state elections, widely seen as rigged to keep the National Conference-Congress alliance in power, became a turning point. Disillusioned youth turned to militancy, and 1989 saw the rise of Hizbul Mujahideen — an ISI-supported, pro-Pakistan jihadist outfit — marking a shift from separatism to religious extremism. It was around this time that the pandits in the valley started fearing for their lives and properties.

By the late 1980s, Kashmiri Pandits faced rising threats. High-profile assassinations, such as that of BJP leader Tika Lal Taploo and Judge Neelkanth Ganjoo, created an atmosphere of fear. Pandits appeared on hit lists and felt increasingly unsafe in their ancestral homes.

The situation reached its peak on January 19, 1990, also known as the “Exodus Day” – the day Farooq Abdullah resigned and Governor’s Rule was re-imposed. That night, communal slogans and threats reverberated through the Valley. Militants attacked Hindu homes, committed rapes, and issued ultimatums to “convert, leave, or perish.” Over 75,000 Pandits fled in January alone, and nearly 70,000 more in the following months, according to the Kashmiri Pandit Sangharsh Samiti. At least 650 Pandits were reportedly killed.

Though Governor Jagmohan is often blamed for failing to ensure their safety, journalist Gowhar Geelani notes that senior officials had urged him to protect the Pandits. Instead, Jagmohan offered logistical support for their departure rather than guaranteeing their security.

To date, no formal commission or investigative body has been constituted to probe the exodus or the killings, leaving a dark chapter in India’s modern history unresolved.

25 Years On, The Exodus Continues To Haunt

Even after 25 years since the Pandits left their homes, they continue to live as refugees with no sight of their return as yet. The Pahalgam terror attack that took place on April 22 dealt a severe blow to Kashmir’s return to normalcy. A Kashmiri Pandit, while responding to the recent terror attack, said that things could have been better (in Kashmir) if they had been taken more seriously back then.

“This is exactly what happened with us. It is more of the same. This is so tragic. We keep narrating our realities from back then, but they are always taken as stories. Maybe this could have been avoided if the Kashmiri Pandits were taken more seriously from the beginning,” P Bhan, who had to leave her home near Ganpatyar with her family, said.

The story of the Kashmiri Pandits is not just a tale of displacement—it is a reminder of the consequences of political neglect, communal polarisation, and delayed justice. Decades have passed, yet their wounds remain unhealed, their homes abandoned, and their voices often unheard. For normalcy to return to Kashmir – for it to once again reflect the Kashmir of Amir Khusro’s verse, the true heaven on earth – it is important to acknowledge the pain of the Pandit community and prioritise their rehabilitation. Until then, Kashmir’s beauty will remain shadowed by the silence of those who once called it home.