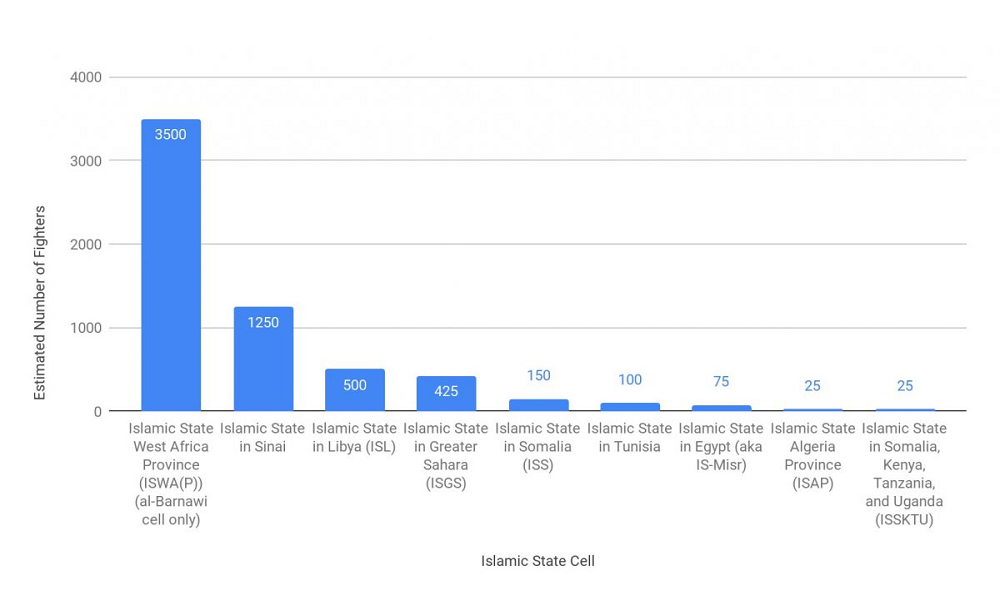

Abstract: To date, little work has been undertaken to analyze the Islamic State’s presence in Africa from a comparative perspective. In an effort to begin to understand the broader landscape of the Islamic State’s existence in Africa, this article presents the first overview of the approximate number of fighters in various Islamic State cells in Africa as of July 2018. Leveraging a compilation of best available open-source data along with interviews with subject matter experts, the authors’ best estimates suggest the presence of approximately 6,000 Islamic State fighters in Africa today, spread over a total of nine Islamic State ‘cells.’

Abstract: To date, little work has been undertaken to analyze the Islamic State’s presence in Africa from a comparative perspective. In an effort to begin to understand the broader landscape of the Islamic State’s existence in Africa, this article presents the first overview of the approximate number of fighters in various Islamic State cells in Africa as of July 2018. Leveraging a compilation of best available open-source data along with interviews with subject matter experts, the authors’ best estimates suggest the presence of approximately 6,000 Islamic State fighters in Africa today, spread over a total of nine Islamic State ‘cells.’

When Jund al-Khilafa, or the “Soldiers of the Caliphate,” pledged allegiance to the Islamic State in Algeria in September 2014, the first African Islamic State affiliate was born. One month later, in October, the Shura Youth Council, a band of 300 fighters in the city of Derna, Libya, comprised largely of Libyans who had fought in the Battar Brigade in Syria’s civil war, followed suit, pledging allegiance to the Islamic State.1 From Nigeria to Somalia, Tunisia to Egypt, and Algeria to the Sahara, between 2014 and 2016, various other Islamic State ‘cells’a—either official wilayat or unofficial affiliated groups—emerged on the African continent.

While the presence of these cells has caused concerns in its own right, they have received more attention, at least in popular discourse, following the late 2017 collapse of the caliphate in Syria and Iraq after the liberation of Mosul.2 Still, with few exceptions,3 there has been little analysis of the strength of the Islamic State’s African cells from a comparative perspective. Leveraging a compilation of best available open-source estimations along with interviews with subject matter experts, this article puts forward the first-ever overview of the approximate number of fighters in various African Islamic State cells today.

The Islamic State Fighter Landscape in Africa

Before delving into data, it bears asking: what accounts for the relative lack of comparative study of Islamic State cells in Africa? More acutely, why, despite the fact that some of these cells have existed for nearly four years, is so little known about fighter numbers? Several explanations can be offered. First, there is an overall scarcity of detailed open-source data on many—though not all—Islamic State cells in Africa. While much writing has been on done on the Islamic State in Libya and in Egypt (Sinai), as well as on the Islamic State’s West Africa Province (formerly Boko Haram), journalistic accounts of smaller Islamic State cells are rare, and existing work only occasionally reports on fighter numbers. While it can be surmised that more detailed estimates exist in classified spaces, data available to journalists, researchers, and academics is conjectural at best, and often relayed in the form of passing comments in written pieces or as broad estimates in press conferences by military spokespeople.4 Second, when open source accounts do provide estimates on numbers of fighters, there are methodological issues surrounding how these estimates were derived. In general, it is difficult to arrive at estimates, particularly for small groups, because fighter numbers are constantly changing in environments in which there is already poor information, and groups often try to prevent information about their sizes from becoming public. Thus, estimates may be derived from rough calculations of initial size, casualties, arrests, movements, size of the area of operation, or changes in the methods of operation. These estimates also often fail to disaggregate a cell’s active fighters from its non-fighting supporters.

Bearing in mind these limitations, the authors gathered open-source information from news organizations, think-tanks, governments, and international organizations, identifying minimum and maximum estimates of the number of fighters in various Islamic State cells for all months for which data was available, from an individual cell’s founding to the present (July 2018). Importantly, they attempted to present a representative “universe” of fighter estimates at various points in time, even if, occasionally, they were not wholly convinced that these estimates were accurate. The authors then conducted informal interviews with subject matter experts in order to formulate the best current estimate of fighter numbers. The estimates presented below are for Islamic State fighters involved in active fighting as opposed to individuals involved in non-kinetic operations, such as supporters, recruiters, financiers, or those living under the rule of an Islamic State affiliate.

The resulting estimates are tentative at best. Even for the intelligence-collection agencies of advanced nations like the United States, estimating numbers of fighters is notoriously difficult. Using only the open source domain—and relying to a significant degree on the authors’ own judgments as subject matter specialists—means that these attempts are far more the result of an art than a science. Thus, given the data’s limitations and the challenges of drawing inferences about fighter numbers from a narrow set of indicators, this is only an incipient attempt at understanding the comparative threat of Islamic State cells in Africa. A brief overview of the findings is presented in Figure 1, followed by a discussion of the evolution and current state of fighter numbers of various Islamic State cells in Africa, from largest to smallest.

Estimated Numbers of Islamic State Fighters in Various African Cells (July 2018)

Islamic State West African Province (ISWAP)

Since 2009, Boko Haram, under the leadership of Abubakar Shekau, became infamous for its deadly insurgency in the Lake Chad Basin of West Africa and for its 2014 kidnapping of the 276 Chibok girls. In March 2015, Shekau pledged allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and the Islamic State; five days later, Baghdadi recognized the pledge. Thus, at least on paper, Boko Haram—as the world had previously known it—ostensibly ceased to exist.b In its place, the Islamic State West African Province (ISWAP) was set up.5 This pledge provoked great concern within the international community—some called Boko Haram’s subsumption into the Islamic State a “marriage from hell”6—a rightful worry in 2015, as the former Boko Haram group increased its violence, especially its suicide bombings, particularly those conducted by women and children.7

By August 2016, tension in the relationship between ISWAP and Islamic State ‘Central’ became apparent, primarily due to the latter’s disdain for ISWAP’s (in their view) overly sweeping interpretation of takfir, or the justification to target and kill apostate Muslims. To rid ISWAP of Shekau, a shrewd but uncontrollable ideologue of whom it disapproved,8 the Islamic State announced in August 2016 that it had replaced Shekau with Abu Musab al-Barnawi, the son of Boko Haram’s founder, Mohammad Yusuf.9 For his part, Shekau has rejected the notion that he has been replaced. Thus, today, ISWAP is led by Barnawi and operates primarily in the Lake Chad Basin region. Shekau, whose group operates alternatively under the international name of Boko Haram or the local name Jama’at Ahl as-Sunnah lid-Da’wah wa’l-Jihad (JAS) but is also sometimes referred to as a second branch of ISWAP, operates near the Sambisa Forest further south.10

When assessing ISWAP’s estimated fighter numbers, the authors only take into account those fighters in Barnawi’s ISWAP group, even though no evidence exists that Shekau has ever fully renounced his affiliation with the Islamic State.c In making this methodological choice, the authors rely on fighter estimates from the U.S. Department of Defense, which in April 2018, put the membership of the Barnawi faction at 3,500.11 (If one were to count Shekau’s faction, this would add another 1,500 fighters, according to the same source.12) As of July 2018, Barnawi’s ISWAP faction is unquestionably the largest Islamic State grouping in Africa, with roughly three and half times as many fighters as the next largest Islamic State cell in Africa, Islamic State-Sinai (in Egypt), and more fighters than all other Islamic State cells in Africa combined.

Yet, despite its still relatively large fighter base, Barnawi’s ISWAP cell today has (as would be expected) lower fighter numbers than when the Barnawi and Shekau groups—which today are highly distinct in various ways13—were unified under the moniker of Boko Haram before their 2016 split. In spring 2014, the U.S. Department of State estimated that the number of Boko Haram fighters, before the group had pledged allegiance to the Islamic State, ranged from “hundreds to a few thousand.”14 When Boko Haram emerged on most people’s ‘radar screens,’ following the April 2014 Chibok kidnappings, estimates of fighter numbers verged on the ludicrous: the Cameroonian Ministry of Defense suggested in July 2014 that the group had between 15,000 and 20,000 fighters; a Nigerian journalist suggested that it had 50,000 fighters.15 By the end of 2014, Boko Haram had surpassed the Islamic State to become the world’s deadliest terrorist group, with estimates from February 2015—just prior to Shekau’s pledge—placing Boko Haram at between 7,000 to 10,000 fighters16 by one estimate in which the group was perhaps speciously compared to “other, similar groups,” and a lower 4,000 to 6,000 “hard-core fighters” the same month, according to estimates from U.S. intelligence officials.17 For their parts, researchers Daniel Torbjörnsson and Michael Jonsson note that in interviewing security officials in Nigeria in May 2017, consensus existed that the Barnawi faction was significantly larger than the Shekau faction, with an estimated 5,000 fighters compared to Shekau’s 1,000 fighters.18 As previously noted, the authors take 3,500 as the best estimate of the Barnawi faction’s number of fighters as of July 2018.

Islamic State in Sinai

Ansar Beit al-Maqdis (ABM), or “Supporters of Jerusalem,” is an Egypt-based insurgent group founded in the aftermath of Hosni Mubarak’s ouster as president in early 2011 during the Arab Spring. ABM—which would eventually become the Islamic State in Sinai three years later, in November 2014—had initially declared itself al-Qa`ida’s wing in the Sinai, although it never became a formal affiliate of al-Qa`ida.20 After conducting a series of attacks against Israel during the conflict in Gaza in July 2014, ABM shifted its focus back to attacking Egypt.

ABM pledged bay`a to the Islamic State in November 2014.21 Its pledge was accepted three days later, marking the swiftest recognition of any pledge made by an African organization to the Islamic State. Since then, the Islamic State in Sinai has launched several significant attacks, most notably claiming credit for the October 2015 downing of Russian Metrojet Flight 9268, which killed all 224 passengers and crew members.d The Islamic State in Sinai appears to have had, at the time, relatively close links with Islamic State Central, when compared to other African Islamic State groupings, serving as one of the few African cells believed to have received funding, weapons, and tactical training from Islamic State Central.22 e

With an estimated 1,000 to 1,500 fighters, the Islamic State in Sinai is the second-largest African Islamic State cell,f smaller only than the Islamic State West Africa Province (Barnawi faction). Interestingly, it seems as though ABM’s November 2014 pledge to the Islamic State helped boost its fighting force: while reports suggest that ABM had an estimated 700 to 1,000 fighters in January 201423 (before it had pledged allegiance to the Islamic State) as of July 2018, best estimates—which, as detailed below, have remained consistent for years—suggest that the Islamic State in Sinai has about 50 percent more fighters, at between 1,000 to 1,500. Indeed, what is particularly striking is the relative consistency in the Islamic State in Sinai’s fighter numbers. With few exceptions,g the vast majority of open sources agree that the group has maintained between 1,000 and 1,500 fighters, with estimates suggesting this range in November 2015,24 January 2016,25 May 2016,26 October 2016,27 November 2017,28 and May 2018.29 For the purposes of arriving at a single number for the group’s current fighting force, the authors took the average, settling on 1,250.

Islamic State in Libya

Perhaps no other Islamic State affiliate in Africa has attracted as much concern as the Islamic State in Libya. Indeed, various Islamic State communications portrayed it as the most important space for the Islamic State outside of Iraq and Syria.30 One result of which is that data on its fighter numbers is more robust and comprehensive when compared to what is known about other African cells.

More than any other Islamic State cell in Africa, the Islamic State in Libya has experienced as a result of fighting in Syria a profound rise and subsequent fall in its estimated fighter numbers. The group emerged in Derna in April 2014, when a band of just 300 fighters—many of whom had returned from fighting in Syria in the mostly Libyan-composed Battar Brigade—returned to Libya and allied with members of pre-existing jihadi groups, like Ansar al-Sharia, calling themselves the Islamic Shura Youth Council (Majlis Shura Shabab al-Islam). Though they emerged in Derna in April 2014 and expressed ideological affinity with the Islamic State in June 2014, it was not until October 2014 that the Islamic Shura Youth Council pledged allegiance to al-Baghdadi. In return, al-Baghdadi recognized the pledge one month later and then announced the formation of three branches of the Islamic State in Libya: Cyrenaica, Fezzan, and Tripolitania.31

By November 2014, a month after its inception, the three Islamic State branches in Libya had a combined total of an estimated 500 fighters.32 However, by summer 2015, when the group scored a major victory with the June takeover of Sirte after losing Derna to al-Qa`ida-aligned militias, its ranks had nearly tripled, to 3,000 fighters, according to one estimate from The Washington Post.33 By November and December 2015, the United Nations estimated the Islamic State in Libya to number some 2,000 to 3,000 fighters,34 while The Wall Street Journal, relying on estimates from Libyan intelligence officials and civilians, reported that its forces were 5,000-strong.h By April 2016, the U.S. Department of Defense estimated that there were between 4,000 and 6,000 fighters.35 These numbers held steady throughout the summer of 2016, with the CIA estimating the group had a fighting force of between 5,000 and 8,000 Islamic State fighters in June 201636 and the BBC, relying on unspecified sources, reporting 5,000 fighters in August 2016.37 i

By December 2016, a coalition of Libyan forces, combined with a concerted U.S. airstrike campaign, had expelled the Islamic State from major cities, including Sirte. Although observers feared that Libya would become one of the most popular destinations for fighters fleeing defeat in Syria and Iraq, throughout 2017, one journalist, citing U.S. officials, pegged the number of fighters in Libya at 200, while another journalist, citing Libyan officials, put it at 500.38 Currently, the authors’ best but tentative estimate is 500.

The Islamic State in Greater Sahara

While the largest three cells discussed above represent roughly 87 percent of the total fighters belonging to African Islamic State cells (5,250 out of 6,050 fighters), here the authors consider a number of smaller cells that, despite their size, nonetheless pose threats, beginning with the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS).

The Islamic State in Greater Sahara came to rise, at least nominally, in May 2015 when Adnan Abu Walid Sahraoui, a senior leader for an al-Qa`ida-aligned group known as al-Mourabitoun, pledged allegiance to al-Baghdadi.j The overall leader of al-Mourabitoun, Mokhtar Belmokhtar, rejected the notion that Sahraoui’s pledge was undertaken on behalf of al-Mourabitoun; instead, he said Sahraoui’s pledge was his alone. Sahraoui and dozens of fighters thus left al-Mourabitoun and formed their own Islamic State grouping, the Islamic State in Mali, which later came to be known as the Islamic State in Greater Sahara. While ISGS launched several notable attacks in 2016—including an attempted October 2016 Koutoukale Prison break in Niamey—it was the group’s October 2017 Tongo Tongo ambush, which resulted in the deaths of four U.S. service members and five Nigeriens, that brought ISGS to global attention.39 As of June 2018, ISGS has claimed 15 attacks, though is presumed to be responsible for many more.40

Perhaps as a result of its increased international profile since the Tongo Tongo attack, best available estimates (speculative and sometimes wildly fluctuating though they arek) suggest that as of July 2018, ISGS boasts its largest number of fighters to date. Estimates at the group’s emergence in May 2015, based on a video of Sahraoui and his followers pledging allegiance to al-Baghdadi, placed its fighter count at 40.41 At the date of the Tongo Tongo attack in October 2017, one journalist, citing a senior U.S. counterterrorism official, put its numbers only slightly higher, at 40 to 60.42 As of April 2018, the U.S. Department of Defense estimated the group as having as many as 300 fighters,43 while various subject matter experts in June 2018 suggested that the number was between 200 and 300.

Screen capture from video of Islamic State in the Greater Sahara leader Adnan Abu Walid Sahraoui’s bay`a to the Islamic State

Héni Nsaibia of the security consultancy Menastream has estimated that as of late July 2018, ISGS has approximately 425 fighters. These are composed of 300 in ISGS—including 100 from Fulani Toleebe, a group composed Katiba Macina defectors45—plus another 125 fighters from Katiba Salaheddine, an ISGS affiliate, which joined the group in mid-2017.46 From the authors’ perspectives, this is the most reliable and comprehensive estimate to date, thus the authors employ Nsaibia’s estimates.

The Islamic State in Somalia

The Islamic State in Somalia (ISS) emerged in October 2015, when former al-Shabaab ideologue Abdul Qadir Mumin pledged allegiance to the Islamic State. Though the pledge has never been formally recognized, the Islamic State in Somalia have increased their operational tempo throughout 2018: according to data from FDD’s Long War Journal, as of July 25, 2018, the Islamic State in Somalia had claimed 67 attacks,47 though it still does not have the capacity to challenge al-Shabaab for jihadi hegemony.48

When it comes to the Islamic State in Somalia’s numbers of fighters, when the group first emerged with Mumin’s breakaway from al-Shabaab in 2015, data reported by FDD’s Long War Journal suggested that it had as few as 20 members.49 There were estimates that its numbers were fewer than 100 fighters by August 2016, according to the same source.50 In October 2016, just after it launched its most notable attack— the takeover of the port town of Qandala, which it held from October to December 2016—Voice of America’s Harun Maruf, relying on intelligence provided by a former Puntland Intelligence Agency official, suggested that the Islamic State in Somalia had between 200 and 300 fighters.51 After it was dislodged from Qandala, fighter numbers seemingly declined: by December 2016, local observers like Mohamed Olad Hassan estimated that the group had only between 100 and 150 fighters.52 By June 2017, a defector from Islamic State Somalia told a local news outlet that the group had only around 70 fighters.53 However, due to an increased recruiting drive—which includes targeting children as young as 10 years old54—in addition to its recent spate of attacks as described above, anecdotal evidence suggests that ISS’s numbers are again on the rise, though not drastically. While one Somali journalist, Abdirisak Mohamud Tuuryare, suggested that there were 300 ISS fighters in May 2018,55 another local Somali journalist put ISS’ numbers at “not more than 100” in July 2018.56 For his part, Caleb Weiss, who studies the group, suggested between 150 and 200 in July 2018.57 The authors take a middle estimate of 150.

The Islamic State in Tunisia

Another smaller African cell is the Islamic State in Tunisia, which emerged when a group called Jund al-Khilafah, or Soldiers of the Caliphate, (JAK-T) pledged allegiance to central Islamic State leadership in a proclamation that was never acknowledged by the latter. While exact estimates vary, consensus remains that the group is small. Two subject matter experts independently assessed fighter numbers of 2558 and 3059 in June 2018. However, according to Tunisia expert Matt Herbert as of June 2018, best estimates put the Islamic State in Tunisia at between 90 and 100 fighters, which came as a result of shifts of fighters, especially in western Tunisia, away from AQIM and toward the Islamic State.60 The organization’s small profile is particularly notable given that Tunisia has been one of the most common country of origin for foreign fighters flowing into Iraq and Syria.61 l The authors employ Herbert’s upper estimate of 100 fighters.

The Islamic State in Egypt (IS-Misr)

The Islamic State in Egypt—distinct from the Islamic State in Sinai, as it is based in the Egyptian mainland—emerged in July 2015. While the organization never pledged allegiance to the Islamic State, it received attention in a May 2017 edition of the weekly magazine published by the Islamic State, which included an interview with an unnamed individual identified as the “Emir of the Caliphate’s Soldiers in Egypt.”62 Among other larger-scale attacks, the Islamic State in Egypt attacked the Italian consulate in Cairo with a car bomb in July 2015, gaining additional notoriety for its ability to attack government and foreign targets in a city otherwise tightly surveilled by security services.63 More notably, Islamic State-Misr was responsible for the deadly twin 2017 Palm Sunday bombings at two Coptic Christian churches, occurring in Tanta and then Alexandria, which killed an estimated 45.

Islamic State-Misr’s current fighter numbers have declined from its peak of late 2015 to early 2016, when the group was estimated to have around 150 fighters.65 Throughout 2016 and 2017, Islamic State-Misr sustained losses and does not seem to have been able to replace them through local recruitment efforts.66 While one anonymous expert estimated in May 2018 the group had 100 fighters,67 Oded Berkowitz, regional director of Tel Aviv-based Intelligence in MAX Security Solutions, has argued that Islamic State-Misr’s current fighter numbers are closer to 50 and 75 fighters.68 However, Berkowitz has also said that it could be the case that significant numbers of Islamic State-Misr fighters are not currently located on the Egyptian mainland, instead having possibly crossed into Libya and linked up with Islamic State-Libya’s desert brigades or having joined the comparatively more powerful Islamic State-Sinai.69 The authors take Berkowitz’s high-end estimate of 75 fighters.

The Islamic State Algeria Province

The Islamic State Algeria Province (ISAP) was the first African Islamic State cell to emerge, but was also one that fizzled out quite quickly. ISAP was founded by a former high-level member of AQIM, Abdelmalek Gouri, whose September 2014 pledge of allegiance to al-Baghdadi was accepted two months later. ISAP made headlines for its 2014 killing of French hiker Hervé Gourdel, whom it captured and beheaded on video in retribution, it claimed, for airstrikes by France in Iraq. Since then, the group has attracted recruits from at least four other AQIM splinter groups, and has launched attacks in Jijel, Constantine, Tiaret, the outskirts of Algiers, Skikda, and Annab, with the latest attack occurring in August 2017.m It also succeeded in running a short-lived outpost in Jabel Ouahch, overlooking the city of Constantine in northeastern Algeria, from which it launched several assassinations, IED ambushes and at least one (failed) suicide bombing.70 However, throughout the course of ISAP’s existence, it has faced sustained and often intense pressure from Algerian security forces, on one hand, and antagonistic elements of AQIM, on the other,71 limiting its growth.

At the time of Gouri’s death in 2014, The New York Times, citing unnamed sources, estimated that ISAP had fewer than 30 fighters. However, the decapitation of its leader, Gouri, who was killed by Algerian security forces after Gourdel’s death, likely contributed to the subsequent unraveling of the group.72 A year later, in 2015, Algerian forces killed 21 more of ISAP’s members,73 seemingly neutralizing a significant portion of what was already a shrinking group. Today, subject matter experts question whether the ISAP’s presence is significant enough to warrant meaningful discussion at all.74 Based on all this, one can conclude that the active Islamic State ‘fighter’ presence in Algeria is minimal, at fewer than 25.

The Islamic State in Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda

In April 2016, a grouping called the Islamic State in Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda (ISSKTU), or Jabha East Africa, pledged loyalty to al-Baghdadi,75 though again, the pledge was never recognized. A breakaway from al-Shabaab, the group was formed by Mohamed Abdi Ali, a medical intern from Kenya who was arrested in May 2016 for plotting to spread anthrax in Kenya to match the scale of destruction of the 2013 Westgate Mall attacks.76 As its name suggests, the group—small as it is—has a multinational composition. As is the case of the Islamic State in Algeria Province, ISSKTU seems to exert more of a nominal presence than an actual one. Beyond a notable June 2016 attack on an AMISOM convoy, the group’s violence has been limited.77 At this point, it is not entirely clear that the one-time Islamic State cell still exists. As such, the authors assume it to have fewer than 25 fighters, if any.

Comparative Analysis

The authors have come up with their best estimate of the approximate number of fighters in various Islamic State cells throughout Africa, but it is also useful to compare these metrics against a samplen of other jihadi and non-jihadi organizations in Africa. If the Shekau faction of ISWAP is, as before, excluded, al-Shabaab, al-Qa`ida’s branch in Somalia, is the largest violent extremist organization on the African continent. The Council on Foreign Relations estimated al-Shabaab to have a membership of between 3,000 and 6,000 in January 2018,78 while the U.S. military estimated the range to be between 4,000 and 6,000 fighters in April 2018.79 The authors use 4,500 as an estimate.

The next-largest non-Islamic State affiliated jihadi group is the coalition of Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimi (JNIM) based in the Sahara, al-Qa`ida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)’s affiliate in Mali, which was estimated to have 800 active fighters in April 2018 by the U.S. Department of Defense,80 a figure in line with an estimate by subject matter expert Héni Nsaibia in early July.81 The authors settle on a flat 800.

Finally, though the group is now mostly defunct, it bears noting that the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), which was led by Joseph Kony, now has an estimated 100 fighters or fewer.82 The authors included these non-Islamic State groups’ fighter numbers in Figure 2.

Estimated Numbers of Fighters in Various Violent Extremist Organizations Across Africa (July 2018)

The Future of the Islamic State in Africa’s Fighters

In this article, the authors have presented what they judge to be the best available estimates for the number of fighters in nine Islamic State cells in Africa. In the main, the authors estimate that there are approximately 6,000 Islamic State fighters spread across nine cells within the continent, which themselves vary dramatically in size. The largest, the Islamic State West Africa Province (al-Barnawi group), has an estimated 3,500 fighters, while cells of the Islamic State in Algeria and the Islamic State in Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda, each have fewer than 25 fighters, the authors estimate.

Before closing, it bears asking just what factors might be at play in explaining the significant variation in size among various Islamic State factions in Africa. While space does not permit an extensive discussion on this front, in general, a group’s number of fighters may depend on a complex set of factors including the extent to which it is capable of recruiting; its sources and amount of funding; the extent and nature of competition with proximate militant groups; the effectiveness of counterterrorism efforts against the group; and a group’s transnational linkages with other organizations; among many others.

Two plausible factors worth highlighting are whether and when a group’s pledge to Islamic State Central was accepted, and second, the nature of the flow of foreign fighters to Iraq or Syria from a group’s home country or region. First, having a pledge of bay`a accepted by Islamic State Central may have bolstered the Islamic State cells’ reputations, helping them attract and retain fighters, and the authors’ intuition is that groups whose pledges were accepted earlier on, before Islamic State Central was pushed onto the defensive in 2015, likely benefited in attracting more fighters. Second, Islamic State African groups may be smaller if more of the country or region’s fighters left to go to Iraq and Syria, whereas those places with higher numbers of Islamic State sympathetic fighters not traveling to Iraq and Syria might have been able to grow larger as a result. The potential relationship between African group size and foreign fighter flows is particularly complex, and the authors especially welcome additional research into how this factor might operate in the cases presented in this piece.

Given the above, what does the future hold for the Islamic State’s fighter presence in Africa? While answers remain conjectural, none of the largest Islamic State cells strike the authors as likely to experience significant growth. The Islamic State West Africa Province is increasingly on the back foot with the more or less effective counterterrorism tactics undertaken by the Nigerian government and the Multinational Joint Task Force, and the Egyptian regime’s brutal counterterrorism tactics against the Islamic State in Sinai—which are now causing a humanitarian catastrophe, according to Human Rights Watch83—likely will dissuade others from moving to join the Islamic State-Sinai. In Libya, geography and the presence of rival militant organizations are oft-cited barriers to Islamic State expansion.84 Instead, the authors imagine that the greatest opportunities for growth are in the smaller cells in Sub-Saharan Africa: namely, the Islamic State in Greater Sahara and the Islamic State in Somalia. Precisely because these cells are small and under-targeted, the presence of even dozens of additional fighters has the potential to engender significant proportional growth. Already, both ISGS and ISS have proven themselves to be capable of meaningful violence. With fewer than 200 fighters, the Islamic State in Somalia occupied the Somali port town of Qandala for nearly two months from October to December 2016, while just a handful of the Islamic State in Greater Sahara’s soldiers were responsible for the deaths of four U.S. service members in the Tongo Tongo ambush in October 2017, marking the biggest U.S. military loss in Sub-Saharan Africa since the 1993 Black Hawk Down attack. However, while proportional growth may occur, neither of these cells is likely to match the Islamic West Africa Province or the Islamic State-Sinai in absolute fighter numbers.

The authors recognize that other phenomena besides fighter numbers—including power of message, sympathy of host communities, outside funding, and capacity to hold territory—are also salient components of understanding a terrorist group’s strength. Appreciating fighter numbers from a comparative perspective, however, represents a crucial first step to better understanding both the landscape of the Islamic State’s presence in Africa and the future of the Islamic State more broadly.