Abstract: Over the past year, mercenaries from the Wagner Group, a private military company with very close ties to the Kremlin, deployed to Mali—first to Bamako, the capital, then to the central part of the country, then in the east all the way to Gao and Ménaka and in the north to Timbuktu. The arrival of Russian mercenaries hastened the departure of French and European forces. However, the Russian private military company did not deploy capable, disciplined, and well-equipped troops to fill the gap, and its brutal and indiscriminate counterinsurgency efforts are serving as a recruiting tool for the jihadis. A year after the arrival of the Russian mercenaries to Mali, the security situation has worsened. Despite ongoing fighting between al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State’s branches in the Sahel, the two terrorist groups are consolidating their sanctuaries and gaining an unprecedented range of action. With concern that Wagner may seek out Burkina Faso as its next client, the Russian mercenaries’ aggravation of the jihadi threat has very concerning implications for the stability and security of the region.

The Wagner Group, a Russian private military company with very close Kremlin ties, currently counts several African governments as clients for what it professes to be a range of security services, including counterterrorism, in a bargain that has seen the group provide military and security services in exchange for mining concessions and political access. But as Christopher Faulkner noted in the June 2022 issue of CTC Sentinel, the Wagner Group “has little interest in genuine capacity building and instead seeks to capitalize and profit on insecurity,” with its “nefarious practices, including opaque and manipulative contracts, disinformation campaigns, election meddling, and severe human rights abuses” posing “a severe threat to the security and stability of African states.”1 However, when seen from the Kremlin’s perspective, the Wagner Group has been a very useful proxy. At low diplomatic and military cost, it has helped advance Moscow’s agenda and created the perception that Russia has greater capacities than it actually does.

This article examines the impact the Wagner Group has had on the jihadi threat environment in the Sahel region, with a significant focus on Mali. The article proceeds in four parts. It first provides some context on the counterterrorism environment in the region, then outlines how the Wagner Group has worked to ingratiate itself with governments in the Sahel. It then examines the Wagner Group’s impact on the jihadi threat picture in Mali and potential future impact in Burkina Faso before providing some brief conclusions. The bottom line is that the Wagner Group has not helped bring security to the region and is in fact aggravating the jihadi threat.

The Counterterrorism Environment

After al-Qa`ida-allied jihadis took over much of northern Mali in 2012 and seemed poised to threaten the capital Bamako, France initiated—at the behest of the Malian government—a military campaign called Operation Serval that within months succeeded in restoring the government’s nominal control over Mali’s territory. The operation did not, however, defeat the jihadi threat,2 with various terrorist groups waging an insurgent campaign in Mali that continues to this day. In 2014, France replaced Operation Serval with a broader regional counterterrorism effort entitled Operation Barkhane, with most of the deployed French forces remaining in Mali.3

In May 2021—in a second coup in the country in nine months—Mali’s current leader, an anti-French military officer named Colonel Assimi Goïta, seized power. In the months that followed, relations between Bamako and Paris went into a downward spiral, with Goïta refusing, and angered by, French demands to hold elections within a reasonable timeframe.4

In February 2022, France announced it was withdrawing militarily from Mali after a breakdown in relations between Paris and the military junta.5 By the summer, Operation Barkhane and a separate French-led European military mission in Mali (Task Force Takuba) had ceased operations.6 France relocated its main counterinsurgency hub to Niger.7

Despite some high-profile successes in removing jihadi leaders from the battlefield—among them, al-Qa`ida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) leader Abu Musab Abdel Wadoud;8 Abu Iyad al-Tunisi, the founder of Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia;9 and the Islamic State’s first regional leader in the Sahel, Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahraoui—Paris had failed to get successive governments in Bamako to make the sort of governance improvements that might have eroded the jihadis’ ability to recruit. Civilian casualties10 produced by French operations, including at a wedding celebration on January 3, 2021, in the Malian village of Bounty,11 had also created anger in the country, which was compounded by the fact that the then Malian government backed12 an initial French version of events that was later discredited by U.N. investigators.13 a

In a March 2022 assessment, the Center for Security and International Studies (CSIS) stated that French failures to initiate deep governance reforms had “helped fuel the expansion of jihadist violence from the north of Mali to the central region, as well as to Niger, Burkina Faso, and the northern borders of Benin and Côte d’Ivoire.”14 Notwithstanding the continuous targeting of high-value targets by French forces and the ongoing war between al-Qaida and Islamic State militants in Mali, in this author’s assessment the French military focus in recent years on the immediate threat of the Islamic State in the tri-border region between Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso provided the al-Qaida jihadi umbrella group Jama’at Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM) with time and space to expand farther in Mali, Burkina Faso, and all the way to Benin and Togo.15

The jihadis still posed a significant threat to Mali when the last French troops left the country in August 2022,16 with militants belonging to JNIMb enjoying a stronghold in Mali’s northeast and central regions, as well as arrayed to the north, south, and east of Bamako.17 In the Sahel as a whole, by the summer of 2022, JNIM was “increasing its control and expanding towards the neighboring coastal countries, with support from [some] local communities,” according to a report published in July by the U.N. monitoring team tracking the global jihadi threat.18 The report stated that JNIM is “the major source of insecurity” in Mali.19 JNIM represents a political threat to the junta in Mali as well, as the group can provide an alternative governance model. This is not the case yet for the Islamic State Sahel Province (ISSP),c which represents a more violent threat but with no viable political governance project so far.

At the time French forces pulled out of Mali, ISSP had been contained by the French military effort and pushed outwards toward the tri-border region of Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso by its more powerful rival JNIM. In May 2022, some Islamic State units signed a ceasefire with some JNIM units in the Gourma region of Mali, but as with other local ceasefires between the warring jihadi groups20 in the region, it did not last long. The overall trajectory is one of steadily growing animosity between the two groups as evidenced by a November 12 clash in the Mali-Burkina Faso border area in which the Islamic State claimed to have killed 80 JNIM fighters.21 Broadly speaking, while JNIM has placed more emphasis on building community support and has thus been able to strengthen its presence across the region, ISSP has had a track record of “indiscriminate and constant violence.”22 Since early March, the group’s brutality against the local population has alienated Tuaregs in the eastern Ménaka region of Mali, pushing some toward a de facto alliance with JNIM militants, allowing the al-Qa`ida affiliate to assert itself in areas such as Azarghazen and Inekar. JNIM was involved in the defending Telataï23 against Islamic State militants in early September and an effort to push back ISSP in Azarghazen24 in late October.25

The Entrance of Wagner

The Wagner Group deployed to Mali in December 2021 at the invitation of the new ruling junta led by Colonel Goïta,26 though it should be noted that the junta still refuses to acknowledge the Russian military company’s presence in the country. The regime’s falling-out with France and other Western countries because of their criticism of the coup meant that it needed to seek other patrons to provide security for the regime and to counter the jihadi threat.27 In the Wagner Group, the new rulers in Bamako saw a company with no qualms about human rights or democracy and that had built up a track record elsewhere in Africa—Libya, Sudan, the Central African Republic, and Mozambique—for promising security to regimes in exchange for cash and concessions to natural resources.28

For a $10.8 million monthly fee and concessions to mining rights, the Wagner Group has provided security to the junta, delivered training, and militarily engaged jihadi forces.29 Around the time the last French troops left Mali, around 800 to 1,000 Wagner mercenaries had deployed to the country.30

Moscow sees the Wagner Group’s deployment to Mali as a low-cost bridgehead for spreading Russia’s influence across West Africa. The logic is that in a zero-sum great power game, if it is Russian mercenary forces providing protection and counterterrorism services to governments rather than the French or American militaries, then Moscow’s clout and economic opportunities31 in the region will grow. With Western countries attempting to isolate Russia because of its war on Ukraine, fostering friendly relations with African governments is important to Moscow.

For the time being, what is constraining the Wagner Group from an even more expansive role in Africa is the fact that it needs to prioritize deploying Wagner mercenaries to Ukraine.32 In July, then commander of U.S. Africa Command General Stephen Townsend stated: “We’ve seen Wagner draw down a little bit on the African continent in the call to send fighters to Ukraine,” adding that most of the Wagner Group’s drawdown had come from Libya and that there had not been redeployments from Mali.33 Nevertheless, the Wagner Group’s prioritization of the Ukraine war seems to have had some effect on its mission in Mali. According to a very well-connected Malian source, Wagner mercenaries in Mali have not benefited from any notable logistical support from outside the country since the late August/early September period and resupply shipments prior to then did not amount to more than guns, ammunition, and rations.34

The Wagner Impact on the Jihadi Threat in Mali

The first Wagner elements arrived in Bamako in the period between December 2021 and January 2022. Within weeks, they were deployed toward the Mopti region of central Mali. The first recorded encounter between Wagner mercenaries and JNIM militants (and the first of Wagner’s casualties in the country) occurred on January 3, 2022, on the road between Bankass and Bandiaguara.35 Multiple encounters with al-Qa`ida militants in central Mali followed, including four in September 2022, two in October, and two in November,36 according to JNIM.37

Up to now, the Wagner Group is only known to have had one significant encounter with the Islamic State when Wagner operatives, along with Mali’s military, were attacked by ISSP in Ansongo on September 1. The Islamic State—without providing visual proof—claimed that it killed “15 Wagner mercenaries” in the encounter.38 The presence of the Wagner Group in the area did not prevent the Islamic State’s Sahel branch from attacking military barracks and facilities in Tessit39 on August 7, resulting in the deaths of at least 42 Malian soldiers.40 The towns of Tessit, Gao,41 and Ménaka42 are still under direct Islamic State threat, despite Wagner’s presence in both towns.43 According to local Tuareg militants sources,44 and to President Mohamed Bazoum of Niger,45 the situation could deteriorate very quickly.

A Lack of Capacity

The deployment of the Wagner Group46 and the departure of French forces severely depleted the counterterrorism capacity of the Malian government. The Russian mercenaries have little experience operating in Mali and have far less capacity than the French to ‘find, fix, and finish’ terrorist targets. Furthermore, the Wagner Group never operates alone in Mali and is logistically completely dependent on their hosts.47

In one notable example of Bamako’s current military inadequacies despite its hiring of the Wagner Group, on June 5 pro-junta Touareg forces, including a commander wearing Russian military fatigues,48 initiated a failed assault on the ISSP-controlled town of Anderamboukane49 in the Ménaka region in the east of Mali with support from the junta in Bamako but without any aerial support or support from Wagner.50 The attacking force underestimated the maneuver capacity of ISSP, which succeeded in luring the attacking forces into a trap 40 kilometers away.51 The town had been under Islamic State control since March. Local sources confirmed that a few days after the failed operation, and following the French departure from the town on June 13, 2022, “poorly equipped” Wagner operatives arrived in Ménaka town.52 According to these sources, they rarely left their barracks and did not venture farther than 10 kilometers away until early November 9-10 when, according to a local Touareg leader,53 Wagner mercenaries carried out “a single offensive patrol” 50 kilometers south of the town of Ménaka.

Targeting of Civilians

The lack of military capacity and ability to target jihadis from the air has seen the Wagner Group defaulting to the sort of heavy-handed tactics that it has used in other conflict zones.54 Not only does the Wagner Group have no regard for civilian casualties, but it appears to have repeatedly and deliberately targeted civilians in jihadi strongholds to deter the jihadis from launching attacks and to coerce the local population to turn against the jihadis living within their midst.55

One example of an apparent Wagner atrocity was noted by Christopher Faulkner in the June 2022 issue of this publication. While the Malian Armed Forces claimed that it killed over 200 militants between March 23 and April 1, 2022, in the town of Moura, he wrote that conflicting reports suggested “that the military along with Wagner mercenaries held the village under siege for four days and indiscriminately executed civilians, killing at least 300 people with some eyewitnesses estimating the total number to be closer to 600.”56

By August 2022, the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) had recorded “approximately 500 civilian fatalities resulting from joint operations involving Wagner and Malian state forces.” ACLED noted that the “distinction between civilians and combatants is increasingly blurred during operations between [Mali’s military] and Wagner, as evidenced by the multi-day massacre in Moura and several other events.”57

ACLED added that Wagner’s deployment in Mali has entailed “mass atrocities, torture, summary executions, looting, the introduction of booby traps as a counter-insurgency tactic, and influence operations in the information environment.”58 According to multiple local sources, as well as reports by the United Nations and Human Rights Watch, the Wagner Group has been complicit in multiple cases of indiscriminate violence against civilians. Often, these have been in towns and villages with a Fulani population.59 The targeting of these towns amounted to the collective punishment of entire communities. An increasing number of Fulanis have been recruited by al-Qa`ida militants in central Mali and farther south,60 as evidenced early on, for example, by an AQIM terrorist attack at a beach resort in Grand Bassam, Côte d’Ivoire, in March 2016 in which two of three attackers were Fulani.61

Other violence against civilians in Mali the Wagner Group has been complicit in include a massacre at the beginning of March in the village of Danguéré-Wotoro near Dogofri, where at least 35 burned bodies were later exhumed,62 and a massacre a few days later of 33 civilians (29 of whom were Mauritanian nationals) in the region of Ségou near the Mauritanian border.63 The Wagner Group was also involved in violence against civilians in Diabali,64 Nampala, Sofara,65 and Boni.66 These towns were known to be JNIM strongholds in Niono,67 Djenné, and Douentza circles; or at least logistical hubs for the group.68 According to multiple local sources, JNIM militants use these towns to buy and sell goods, but also to recruit. In early September and late October, Wagner mercenaries were accused of rape, robbery,69 and cattle stealing.70 JNIM claimed that it managed to retrieve some of the stolen cattle and return it to its owners, gaining a propaganda win.71 Wagner forces were also reported to be involved in a massacre of over a dozen civilians in the Ségou72 and Mopti regions.73

The Jihadi Fightback

Since January 2022, Katiba Macina (KM), a JNIM subgroup active in central Mali, has been the main target of joint military operations conducted by Wagner and Malian armed forces in central Mali. In response to Wagner’s joint deployment with the Malian army, the militants adopted a behavior that was very similar to AQIM’s behavior in the wake of the January 2013 French intervention: retreating back to safe havens and avoiding getting into armed clashes so that they could assess the capacity of their adversary. There were two movements of militants in the first weeks of 2022. One was westward, with KM/JNIM militants retreating to IDP camps in neighboring Mauritania where some of their commanders had family ties.74 The other was southeastward to Burkina Faso.75 The strategy was to absorb the energy of the Wagner offensive and then to counter at a time of their choosing.

The KM branch of JNIM launched its counterattack on March 4, 2022, when they killed more than 40 military personnel in an attack on a barracks in Mondoro.76 JNIM announced in Fulani and in Bambara that “the attack aimed to avenge the Dogofri massacre perpetrated by Malian and Wagner operatives.”77 Wagner operatives were active in the same area at the time of the attack, and they were not of any assistance to the attacked Malian forces. On April 24, JNIM intensified its fight back by launching simultaneous attacks on the Sévaré, Niono, and Bapho Malian army camps.78

JNIM has continued its efforts to win ‘hearts and minds’ in Mali in the wake of the French withdrawal, gaining it some support among the local population, mostly among Fulani elements hostile to the Malian armed forces and the Wagner Group, and Tuareg elements that share JNIM’s hostility toward the Islamic State.79 d The Wagner deployment has created more fertile ground for such outreach efforts. In August 2021, as rumors of a forthcoming Wagner deployment began to spread, the ethnic Tuareg head of JNIM, Iyad Ag Ghali, mentioned Russia for the first time among the enemies of the group. Not only has the Wagner presence in Mali allowed the group to play up Russia as a bogeyman, but the Wagner Group’s atrocities against civilians have provided JNIM with a powerful recruitment tool. According to multiple local and regional sources, there was a surge in jihadi recruitment in central Mali between May and July 2022.80 There was also an increase in fundraising by jihadi groups in markets and mosques in the period between late September and October 2022.81

The French withdrawal also made it easier for JNIM to operate in urban areas and have senior leaders operate and meet more openly with less fear of being targeted by airstrikes. On August 6, just days before France completed its military withdrawal, French forces carried out an airstrike82 neutralizing JNIM fighters who had gathered in the Telatai region near the Niger border.83 e

In the author’s assessment, a few years back, JNIM took the political decision to focus on attacking military targets and to avoid indiscriminate mass shootings,f with one high-profile example being the group’s July 20-21 offensive84 that culminated with the attack on the Kati barracks.85 JNIM’s current official policy is to not carry out attacks against ‘soft targets,’ even though, in the wake of Wagner atrocities, some inside JNIM command are arguing for the return of such “vengeful” attacks.86 Unofficially, the group continues to kill and pressure civilians. One of the bloodiest attacks by a JNIM unit in 2022 occurred in Dialassagou87 on June 18 when at least 132 civilians were killed for “collaborating with the Malian army.” JNIM officially denied responsibility, just as it denied responsibility for the Solhan massacre in Burkina Faso in 202188 as neither attack matched the group’s declared policy. In the wake of the fight with the ISSP, JNIM units active in Tamalat, Gao, and Ansongo committed indiscriminate killings of civilian populations they viewed as having accommodated Islamic State militants or collaborated with them.89

In addition, JNIM has been carrying out intimidation campaigns, like the Boni siege that lasted from May to September 202290 and assassinations that stay generally unclaimed by the group in its areas of activity.91

The Rise in Jihadi Violence

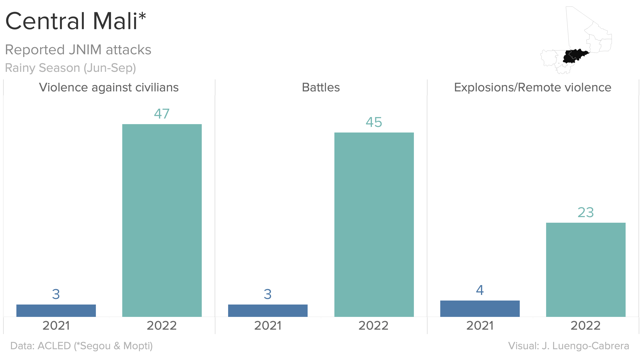

Each year between June and September, there is generally a drop in attacks in Mali because of the rainy season. Roads become very difficult for both the army and terrorist groups. But 2022 witnessed a record number of JNIM attacks during the rainy season: 47 attacks against civilians; 45 armed clashes with military forces, including MINUSMA;g and 23 IED and “explosions/remote violence”h forms of attacks in central Mali. By comparison, in the 2021 rainy season, the corresponding metrics for central Mali were three attacks on civilians, three attacks on military forces, and four cases of explosions/remote violence. (See Figure 1.92)

Figure 1: JNIM attacks in central Mali during the rainy seasons of 2021 and 2022. This graphic and the others were made using ACLED data by Jose Luengo-Cabrera, a Crisis Risk and Early Warning Specialist at the UNDP Crisis Bureau.

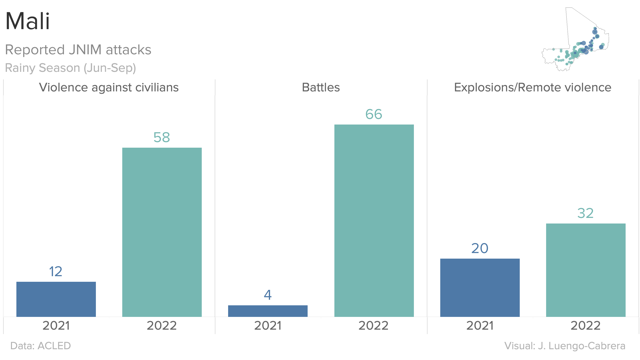

For Mali as a whole, there was also a significant rise in JNIM attacks across these categories between the 2021 and 2022 rainy seasons. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2: JNIM attacks in all of Mali during the rainy seasons of 2021 and 2022

Overall, when attacks by the Islamic State and other entities are added to the mix, there has been a dramatic increase in political violence in Mali since the Wagner deployment. According to ACLED, “both civilian fatalities and total fatalities from organized political violence recorded in the first six months of 2022 surpassed the numbers recorded in all of 2021.”93

An October 2022 report by the United Nations painted a bleak picture of the security landscape in Mali following the French pull-out, noting that “while the Malian Defence and Security Forces continued to conduct military operations aimed at stabilizing the center of the country, the overall security situation remained of deep concern.”94 The report further noted that Mali had in the previous months suffered a “spike in the activities of extremist elements affiliated with Jama’at Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin and Islamic State in the Greater Sahara [ISSP], leading to increased threats against civilians and attacks on the Malian Defence and Security Forces and MINUSMA. In addition, insecurity has continued to expand to the west and south of the country, where Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin and unidentified elements carried out attacks.”95

The U.N. report also drew attention to JNIM’s persistent targeting of Malian forces in urban centers. It stated that in recent months JNIM had imposed strict social and political norms on the local population in several of its strongholds and that reprisal attacks against communities for their purported cooperation with Malian junta forces had increased.96

On October 26, Victoria Nuland, a senior U.S. State Department official, in speaking about Mali, highlighted the U.S. government’s concern over “the constraints that both the government and Wagner forces have put on [MINUSMA’s] ability to operate and fulfill their mandate,” and “the fact that terrorism is going up, not down, and that we are firmly of the view that Wagner works for itself, not for the people of the country that it comes to.”97

The removal of French aerial assets and special forces from Mali has also allowed the Islamic State to capitalize with ISSP taking over the town of Telatai on September 6.98 By October, the Islamic State was gaining strength in northeast Burkina Faso in the tri-border region between Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger,99 and had claimed its first attacks in northern Benin100 while roaming freely101 in the Ménaka and Gourma regions of Mali, taking over the rural Ansongo district near the border with Niger. Hundreds were killed and thousands displaced as the Islamic State militants pushed deeper into Mali from their pre-existing strongholds near the eastern borders.102 By November, in a sign of ISSP’s increased confidence and a possible pivot away from brutalizing the local population, there were indications that the group had started to try to carry out ‘governance’ functions within its Mali strongholds, including destroying drugs and handing out free medications.103

Overall, the trend is for increasing Islamic State activity in Mali. According to ACLED data, there were 34 ISSP attacks in Mali during the June through September rainy season in 2021 and 60 in 2022.104

As noted earlier, after repeated failures to counter ISSP, JNIM has been expanding its presence in the Ménaka region in order to fight the Islamic State militants. and with the tacit approval of local factions. The AQIM offshoot is successfully capitalizing on both abuses carried out by both ISSP and the Wagner Group to ‘win hearts and minds,’ even though JNIM’s ongoing war against ISSP is exhausting the al-Qa`ida affiliate financially and militarily.105 This might explain the notably quick, and relatively cheap, resolution of some of the latest JNIM foreign hostages cases in both Mali106 and Burkina Faso.107 The abduction of a German national in Bamako,108 on November 20, was both a function of the reach of JNIM into the Malian capital and its need of financial resources.109

The Potential Future Wagner Impact in Burkina Faso

If the Wagner Group becomes active in Burkina Faso, it is possible it will also aggravate the jihadi threat there. In Burkina Faso, JNIM operations have in recent months increased and grown bolder. JNIM’s October 24 attack on an army barracks in Djibo, a town the terrorist group has blockaded for months,110 which resulted in the freeing of more than 64 detainees was a significant blow to the new junta in power and a ‘PR’ coup for JNIM especially as most of the freed detainees were elderly and very young Fulani men.111 The army retaliated by bombarding the Holdé area, causing 49 civilian casualties,112 according to a local NGO source,113 and 42, according to jihadi sources.114

After five years of jihadi insurgency,115 JNIM constitutes the main jihadi threat to Burkina Faso.116 A series of coups in Ouagadougou has destabilized Burkina Faso and distracted its military from countering a severe jihadi threat. In late September 2022, a new junta, led by army captain Ibrahim Traoré, came to power and immediately adopted an aggressive stance toward France and a friendly posture toward Russia.117 The latest effort by the junta to recruit civilian volunteers118 will most probably further aggravate the security situation. In November, Burkina Faso’s newly appointed prime minister asked France to help fund and arm119 the “90,000 volunteers.”120 However, according to a French official,121 this demand came with many other irrational demands that, unanswered by France, could ‘justify’ the new military rulers of Burkina Faso turning to Russia. According to the same source, Mali is playing a very active role in the rapprochement between Russia and Burkina Faso. The source added that the new authorities in Ouagadougou seem to be following the ‘Malian playbook’ by suspending in early December the broadcasting of Radio France International.122 It was noteworthy in this regard that in early December, Burkina Faso Prime Minister Kyélem Apollinaire de Tambèla made a trip to Russia via Bamako.123

There is concern the newly installed military junta in Burkina Faso will also hire the Wagner Group.i There are suspicions (though not proven) that Moscow played a role in instigating the coup,124 with demonstrations in support of the junta featuring Russian flags125 and the Wagner Group’s founder, Yevgeny Prigozhin, among the first to praise Captain Traoré’s takeover.126 The jury is still out on whether and to what degree the junta will lean toward Moscow and the Wagner Group. To some degree, Traoré’s anti-French stance seems to have been designed to mobilize popular support in order to guarantee the success of his coup, and it is not clear what his next steps will be.127

It is important to note that French Task Force “Sabre” has had a continuous presence in a Ouagadougou suburb since 2009 and remains deployed there.128 France is currently evaluating all options, including withdrawing its forces from Burkina Faso.129 It is possible that the French presence could be reduced to a very small force by the beginning of 2023.130

Nevertheless, if Wagner becomes active in Burkina Faso, it will also likely aggravate the jihadi threat131 there, as well as potentially allowing the jihadis to increasingly threaten Togo132 and Benin,133 where jihadi activity has been increasing in recent months.134

Conclusion

The deployment of the Wagner Group to Mali has strengthened and energized jihadi groups, providing them with not only a recruitment tool, but a much more favorable operating environment in Mali. As noted, there was a surge in JNIM attacks across Mali in the 2022 rainy season compared to the previous year’s rainy season, and attacks by the Islamic State within Mali also increased across these time periods.

While the junta and the Wagner Group have engaged militarily with jihadi groups in central Mali, they have shown little interest in confronting JNIM activity in Kayes, Koulikouro, Nara, and all the way to Yélimané135 west of the capital Bamako, nor al-Qa`ida militants consolidating positions in Sikasso, Koutiala, and on the border area with Côte d’Ivoire. The strengthening jihadi presence in this border region and the proselytization activities of jihadi preachers on both sides of the border has the potential to also destabilize Côte d’Ivoire.136

In the wake of the Wagner deployment and the ruling junta’s turn toward Moscow and away from democracy, there has been a rush to the exits by international forces from Mali following the French withdrawal. Egypt suspended its participation in MINUSMA137 in July; Germany also suspended its own operations in the U.N. force in August and again in September.138 Berlin plans to reduce German troop levels in Mali from the summer of 2023 onwards and to pull out all troops by May 2024 at the latest.139 The United Kingdom and Côte d’Ivoire announced in November that they would also be pulling their troops from the U.N. peacekeeping force, with Sweden and Benin also having announced exits.140 The troop withdrawals risk undermining what is a vital peacekeeping mission, further destabilizing Mali. MINUSMA has been providing most of the post-battle medical evacuations of Malian forces as well as much of the civilian and military air transport between Bamako and the north. It has also been protecting important roads where the Malian state is absent or relying entirely on the international force. MINUSMA has also played a key role in investigating and documenting human rights abuses committed by militants as well as government forces.141

There is growing concern that the Wagner deployment to Mali has set off a chain of events that could further destabilize the entire region. On November 17, 2022, NCTC Director Christine Abizaid testified that JNIM “is increasingly threatening capital cities in the Sahel … [and] probably hopes to exploit the departure of French forces from Mali earlier this year to accelerate its growth and entrenchment, including into littoral West African states such as Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo.”142

ACLED reported that “during the first six months of Wagner’s deployment in Mali, it became apparent that the group’s operations negatively impacted conflict dynamics, particularly civilian safety,” and added “as Wagner gradually expands its footprint, there is a high risk that other regions will see developments similar to those in central Mali and neighboring areas.”143

As the one-year mark of the Wagner Group deployment approaches, these trends are even more evident, and there should be concern that any Wagner deployment to Burkina Faso will make the security situation in the Sahel and bordering countries even worse.

Substantive Notes

[a] Between January 2018 and August 2022, there were only two other documented instances of French operations in Mali causing civilian casualties. On September 1, 2020, French forces fired warning shots at a public transport bus between Intahaka and Gao; one passage was killed and two wounded. On June 8, 2021, French forces opened fire on a vehicle 20 kilometers east of Lerneb; three Tuareg civilians were killed and their vehicle burned. Jules Duhamel, “Overview of Operation Barkhane in central Sahel | 1 January 2018 – 29 January 2021,” Jules Duhamel website, n.d.

[b] “JNIM is composed of al-Qa`ida in the Islamic Maghreb’s Sahara Emirate, Ansar Dine, Katiba Macina, al-Mourabitoun, and a majority of the Burkinabe militant group Ansarul Islam.” Jason Warner, Ryan O’Farrell, Héni Nsaibia, and Ryan Cummings, “Outlasting the Caliphate: The Evolution of the Islamic State Threat in Africa,” CTC Sentinel 13:11 (2020).

[c] In March 2022, Islamic State fighters in the Sahel were granted the status of a standalone Islamic State province. Previously, the group had operated as the Greater Sahara branch of the Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWAP-GS). See Wassim Nasr, “#Mali l’#EI revendique l’attaque de la base #Tessit avec importantes prises de guerre …,” Twitter, March 23, 2022.

[d] The main recruitment reservoir of ISSP is among Fulani populations across the border in Niger.

[e] The Wagner Group made many attempts to paint the departing French forces as a power that massacred Muslims. In April 2022, the French military stated that it had videos of Russian mercenaries burying bodies near an army base in Gossi in northern Mali shortly after French forces had withdrawn from the base in an attempt to frame them. Wassim Nasr, “France says mercenaries from Russia’s Wagner Group staged ‘French atrocity’ in Mali,” France24, April 22, 2022.

[f] The last mass shooting attack committed by JNIM was the Aziz Istanbul restaurant attack on August 13, 2017, in Ougadougou, Burkina Faso. The attack remained unclaimed and initiated an internal debate in the ranks of AQIM, al-Qa`ida central, and its branches, and the issue was discussed by the Hattin committee.

[g] MINUSMA is the the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali.

[h] “ACLED classifies Explosions/Remote violence events as asymmetric violent events aimed at creating asymmetrical conflict dynamics by preventing the target from responding. A variety of tactics are considered Explosions/Remote violence including bombs, grenades, improvised explosive devices (IEDs), artillery fire or shelling, missile attacks, heavy machine gun fire, air or drone strikes, chemical weapons, and suicide bombings.” See “Explosions/Remote Violence in War,” ACLED, March 22, 2019.

[i] On December 14, President Nana Akufo-Addo of Ghana publicly alleged during a meeting with U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken that “today, Russian mercenaries are on our northern border. Burkina Faso has now entered into an arrangement to go along with Mali in employing the Wagner forces there.” He added that, “I believe a mine in southern Burkina has been allocated to them as a form of payment for their services. Prime minister of Burkina Faso in the last 10 days has been in Moscow. And to have them operating on our northern border is particularly distressing for us in Ghana.” The allegations by Ghana’s president have not been publicly substantiated, and the government of Burkina Faso vehemently denied the allegations. “[Remarks of] Secretary Antony J. Blinken and Ghanaian President Nana Akufo-Addo Before Their Meeting,” U.S. State Department, December 14, 2022; Anthony Osae-Brown, “Ghana Alleges Burkina Faso Paid Russian Mercenaries With Mine,” Bloomberg, December 15, 2022; “Les mercenaires Wagner présents au Burkina Faso, affirme le président ghanéen,” Monde, December 16, 2022.

Citations

[1] Christopher Faulkner, “Undermining Democracy and Exploiting Clients: The Wagner Group’s Nefarious Activities in Africa,” CTC Sentinel 15:6 (2022).

[2] Michael Shurkin, France’s War in Mali: Lessons for an Expeditionary Army (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2014).

[3] Catrina Doxsee, Marielle Harris, and Jared Thompson, “The End of Operation Barkhane and the Future of Counterterrorism in Mali,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 2, 2022.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] “EU’s Takuba force quits junta-controlled Mali,” France24, July 1, 2022.

[7] Tiemoko Diallo, “Islamist militants in Mali kill hundreds, displace thousands in eastern advance,” Reuters, October 14, 2022; Wassim Nasr, “#Niger l’ops @ArmeesNiger a eu lieu à Ekarafane, avec un appui français …,” Twitter, December 14, 2022.

[8] Wassim Nasr, “Implications of the AQIM new leadership,” Newlines Institute, February 8, 2021.

[9] Wassim Nasr, “#AQIM in a 33:16 for the 1st time admits the death of Abu Iyadh alTunsi #Tunisia & Yehya Abu alHumam …,” Twitter, February 27, 2020.

[10] Jules Duhamel, “Overview of Operation Barkhane in central Sahel | 1 January 2018 – 29 January 2021,” Jules Duhamel website, n.d.

[11] “French airstrike in Mali killed 19 civilians, UN investigators find,” France24 English, March 30, 2021; “Frappes françaises au Mali : bavure ou bombardement de jihadistes?” France24, February 2, 2021; “UN investigation concludes French military airstrike killed Mali civilians,” UN News, March 30, 2021.

[12] Buubu Ardo Galo, “#Bounti- La version officielle de l’armée malienne (enfin) disponible …,” Twitter, January 7, 2021.

[13] “UN investigation concludes French military airstrike killed Mali civilians.”

[14] Doxsee, Harris, and Thompson.

[15] Menastream, “#BurkinaFaso-#Togo: 1st official #JNIM claim for ambush on Togolese forces on the border between Burkina and Togo …,” Twitter, November 19, 2022.

[16] “Last French troops leave Mali, ending nine-year deployment,” Al Jazeera, August 16, 2022.

[17] “Thirtieth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2610 (2021) concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities,” United Nations Security Council, July 15, 2022.

[18] Ibid.

[19] “Situation in Mali : Report of the Secretary-General,” United Nations, October 3, 2022.

[20] “Thirtieth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team;” author interviews, local sources and French sources, 2022.

[21] Wassim Nasr, “#Sahel l’#EI revendique un affrontement avec le #JNIM dans une localité frontalière entre le …,” Twitter, November 20, 2022.

[22] “Thirtieth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team.”

[23] According to multiple local and regional sources. Author interviews; identities, names, and dates withheld.

[24] Wassim Nasr, “#Mali #Ménaka (2) photos #EI #Sahel de la bataille rangée d’#Azarghazen avec le #JNIM #AQMI …,” Twitter, November 2, 2022.

[25] “Mali : près de 1 000 victimes du groupe Etat islamique depuis mars,” France24, September 12, 2022; “Dozens Reportedly Killed In Islamic State Attack in Mali,” Voice of America, September 9, 2022.

[26] Doxsee, Harris, and Thompson.

[27] Faulkner.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.; Doxsee, Harris, and Thompson.

[30] Faulkner.

[31] “Burkina Faso grants permit for new gold mine,” Africa News, August 12, 2022.

[32] Andrew Higgins and Matthew Mpoke Bigg, “Russia Looks to Private Militia to Secure a Victory in Eastern Ukraine,” New York Times, November 6, 2022.

[33] Andrew Eversden, “Russia pulls some Wagner forces from Africa for Ukraine: Townsend,” Breaking Defense, July 29, 2022.

[34] According to a local source. Author interview; identity, name, and date withheld.

[35] Wassim Nasr, “#Mali une partie de la vidéo (3:28) tournée par des jihadistes #JNIM #AQMI après l’IED qui a frappé opératifs russes …,” Twitter, January 12, 2022.

[36] Menastream, “#Mali: #JNIM claims a complex dual-IED ambush against the coalition of …,” Twitter, November 24, 2022.

[37] Wassim Nasr, “#Mali 4 altercations avec #Wagner revendiquées par #JNIM #AQMI pour septembre …,” Twitter, October 11, 2022.

[38] Wassim Nasr, “#Sahel l’#EI revendique pour la 1ere fois 2 attaques au #Benin 6morts …,” Twitter, September 15, 2022.

[39] Wassim Nasr, “#Mali #Tessit 08.08 l’#EI #Sahel a conduit 2attaques simultanées contre camp FAMa brûlé …,” Twitter, August 9, 2022.

[40] “42 Malian Soldiers Killed in Suspected Jihadi Attacks,” Voice of America, August 10, 2022.

[41] Wassim Nasr, “#Mali l’#EI #Sahel s’attaque à un petit campement de déplacés internes à ~7km de la ville de #Gao …,” Twitter, November 22, 2022.

[42] Marc Perelman, “‘Jihadist flag likely to fly’ over Malian town of Ménaka, Niger’s president warns,” France24, September 23, 2022.

[43] Jules Duhamel, “Areas of Operation – Wagner Group (Mali),” Jules Duhamel website, July 24, 2022.

[44] According to multiple local and regional sources. Author interviews; identities, names, and dates withheld.

[45] Perelman.

[46] Duhamel, “Areas of Operation – Wagner Group (Mali).”

[47] According to multiple local and regional sources. Author interviews; identities, names, and dates withheld.

[48] Wassim Nasr, “#Mali FAMa GTIA8, #MSA & #GATIA. On remarque le treillis russe du général Gamou en …,” Twitter, June 5, 2022.

[49] Wassim Nasr, “#Sahel #Mali nouvelles photos d’allégeance au nouveau calife de l’#EI depuis …,” Twitter, December 4, 2022.

[50] Wassim Nasr, “#Mali l’entrée des premiers véhicules de la force #MSA #GATIA GTIA8 FAMa dans …,” Twitter, June 5, 2022.

[51] According to a Tuareg security source. Author interview; identity, name, and date withheld.

[52] According to a Tuareg faction commander currently working along Wagner in the Ménaka. See also “French Troops quit northeastern Menaka military base in Mali,” Africa News, June 14, 2022.

[53] Author interview; identity, name, and date withheld.

[54] Ladd Serwat, Héni Nsaibia, Vincenzo Carbone, and Timothy Lay, “Wagner Group Operations in Africa: Civilian Targeting Trends in the Central African Republic and Mali,” ACLED, August 30, 2022.

[55] “Les opérations du groupe Wagner en Afrique,” ACLED, August 30, 2022.

[56] Faulkner.

[57] Serwat, Nsaibia, Carbone, and Lay.

[58] Ibid.

[59] “Mali : ce que l’on sait sur le charnier de Niono,” Jeune Afrique, March 8, 2022.

[60] Andrew McGregor, “The Fulani Crisis: Communal Violence and Radicalization in the Sahel,” CTC Sentinel 10:2 (2017).

[61] Wassim Nasr, “#AQMI les assaillants #GrandBassam un ivoirien #Mourabitoun …,” Twitter, March 17, 2016.

[62] “Mali: New Wave of Executions of Civilians,” Human Rights Watch, March 15, 2022.

[63] “Malian and ‘white’ soldiers involved in 33 civilian deaths-UN experts,” Africa News, August 5, 2022.

[64] David Baché, “Exactions de l’armée malienne et de ses supplétifs russes: la zone de Sofara – Témoignages (1/2),” RFI, March 14, 2022.

[65] Ibid.

[66] “In central Mali, victims and persecutors live together,” International Federation for Human Rights, November 24, 2022.

[67] Benjamin Roger, “Mass grave in Niono: MINUSMA accuses Malian army and Wagner Group,” Africa Report, March 15, 2022.

[68] “Mali: New Wave of Executions of Civilians.”

[69] David Baché, “Mali: l’armée et ses supplétifs accusés de viols et de pillages à Nia-Ouro,” RFI, September 6, 2022.

[70] David Baché, “Mali: soldats maliens, russes et chasseurs dozos accusés de vols massifs de bétail,” RFI, November 24, 2022.

[71] Wassim Nasr, “#Mali #JNIM #AQMI revendique un affrontement avec les Fama et #Wagner …,” Twitter, October 31, 2022.

[72] David Baché, “Mali: quand il ne reste que la fuite, récits de victimes,” RFI, December 5, 2022.

[73] Jason Burke, “Russian mercenaries accused of civilian massacre in Mali,” Guardian, November 1, 2022.

[74] According to multiple local and regional sources. Author interviews; identities, names, and dates withheld.

[75] According to multiple local and regional sources. Author interviews; identities, names, and dates withheld.

[76] Wassim Nasr, “#Mali ~40 militaires FAMa tués dans une attaque du #JNIM #AQMI contre la base de #Mondoro …,” Twitter, March 4, 2022.

[77] Wassim Nasr, “#Mali #Mondoro très significatif que ça soit un jihadiste dogon qui s’exprime …,” Twitter, March 8, 2022.

[78] Wassim Nasr, “#Mali #Mi24 endommagé au sol au camp de #Bapho, donc …,” Twitter, April 24, 2022.

[79] “IntelBrief: Negotiating out of Counterterrorism in the Sahel,” Soufan Center, August 6, 2021.

[80] According to multiple local and regional sources. Author interviews; identities, names, and dates withheld.

[81] According to multiple local sources. Author interviews; identities, names, and dates withheld.

[82] Wassim Nasr, “#Mali communiqué @BARKHANE_OP qui confirme …,” Twitter, August 8, 2022.

[83] Ibid.

[84] Jules Duhamel, “Apercu des Attaques Coordonnées du 21 et 22 Juillet au Mali,” Jules Duhamel website, July 24, 2022.

[85] Annie Risemberg, “Gunfire and Explosions Heard in Mali’s Main Military Town,” Voice of America, July 22, 2022.

[86] According to local source. Author interview; identity, name, and date withheld.

[87] “Mali: The underlying causes of another massacre,” France24, June 21, 2022.

[88] Wassim Nasr, “#BurkinaFaso #JNIM nie catégoriquement son implication dans le massacre de …,” Twitter, June 8, 2021.

[89] Author interviews, identities, names, and dates withheld; multiple Islamic State claims. See Wassim Nasr, “#Sahel #Mali l’#EI renouvelle l’accusation ‘d’exactions des milices apostats d’#AlQaeda [#JNIM] contre …,” Twitter, November 4, 2022.

[90] David Baché, “Au Mali, le blocus jihadiste de Boni enfin levé,” RFI, September 1, 2022.

[91] Author interview, Malian source; identity, name, and date withheld.

[92] ACLED data analyzed by José Luengo-Cabrera, Crisis Risk & Early Warning Specialist at UNDP Crisis Bureau.

[93] “The Sahel: Mid-Year Update,” ACLED, 2022.

[94] “Situation in Mali : Report of the Secretary-General.”

[95] Ibid.

[96] Ibid.

[97] “Digital Press Briefing with Ambassador Victoria Nuland, Under Secretary for Political Affairs, U.S. Department of State,” U.S. Department of State, October 26, 2022.

[98] “Mali unrest: Local sources say nearly 1,000 civilians killed since March,” France24 English, September 12, 2022.

[99] Nasr, “#Sahel #Mali l’#EI renouvelle l’accusation ‘d’exactions des milices apostats d’#AlQaeda [#JNIM] …;” Wassim Nasr, “#BurkinaFaso photos de l’attaque de l’#EI #Sahel à #Déou (12 sept) …,” Twitter, September 24, 2022; Wassim Nasr, “#BurkinaFaso on remarque le même technical équipé de #Zu23 …,” Twitter, July 17, 2022.

[100] Wassim Nasr, “#Bénin prises de guerres de l’#EI au niveau de …,” Twitter, September 23, 2022; Caleb Weiss, “Islamic State claims first attacks inside Benin,” FDD’s Long War Journal, September 17, 2022.

[101] Wassim Nasr, “#Sahel dans un arabe parfait Abou al-Bara [emir du groupe] voue allégeance …,” Twitter, December 12, 2022.

[102] Diallo.

[103] Wassim Nasr, “The #Wagner effect… with a promising after effect… the Islamic State with a new command …,” Twitter, November 4, 2022.

[104] ACLED data collated by the author.

[105] Author interviews; identities, names, and dates withheld.

[106] “Thai doctor recounts Mali kidnap ordeal,” Agence France-Presse, October 27, 2022.

[107] “Kidnapped Polish citizen freed in Burkina Faso – government,” Reuters, June 30, 2022.

[108] David Baché, “Mali: un prêtre allemand porté disparu à Bamako,” RFI, November 21, 2022.

[109] Author interviews; identities, names, and dates withheld. See also Wassim Nasr, “Sahel: entre libérations rapides et longues détentions d’otages,” France24, December 12, 2022; Wassim Nasr, “#Mali : le prêtre allemand a bien été pris en otage au cœur de #Bamako suite à une opération …,” Twitter, December 9, 2022; Elisabeth Pierson, “Mali : enlèvement présumé d’un prêtre allemand au cœur de Bamako,” Figaro, December 9, 2022; and Wassim Nasr, “#Mali la disparition du père Hans Joachim Lohre à #Bamako est une prise d’otage …,” Twitter, November 25, 2022.

[110] “Violence and severe supply shortages leave people across Burkina Faso in dire need,” Medecins Sans Frontieres, October 17, 2022.

[111] Wassim Nasr, “#BurkinaFaso #JNIM diffuse une courte vidéo de 6:10 ‘en prévision d’une longue’ qui détaillerait l’attaque …,” Twitter, October 31, 2022.

[112] “Burkina: l’ONU demande une enquête sur des possibles exactions dans le Nord,” RFI, November 15, 2022.

[113] Author interview; identity, name, and date withheld. See also Wassim Nasr, “#BurkinaFaso source ‘49 victimes civile à #Holdé, tous sous le nom de famille Tamboura …,” Twitter, November 11, 2022.

[114] Wassim Nasr, “#BurkinaFaso #JNIM revendique une attaque à Souli 9.11 & accuse l’armée d’un massacre …,” Twitter, November 11, 2022.

[115] Héni Nsaibia and Caleb Weiss, “Ansaroul Islam and the Growing Terrorist Insurgency in Burkina Faso,” CTC Sentinel 11:3 (2018).

[116] “Thirtieth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team.”

[117] “The old junta leader makes way for the new in Burkina Faso’s second coup of the year,” NPR, October 2, 2022; Clea Caulcutt, “French symbols targeted after Burkina Faso coup,” Politico, October 2, 2022.

[118] Yaya Boudani, “Burkina Faso: pour faire face à la menace terroriste, l’armée recrute 50 000 volontaires,” RFI, October 27, 2022.

[119] Yaya Boudani, “Le Burkina Faso demande à la France de financer et de fournir en armes les VDP,” RFI, December 1, 2022.

[120] “Burkina Faso: le recrutement de volontaires face au terrorisme dépasse les objectifs fixés,” RFI, November 27, 2022.

[121] Author interview; identity, name, and date withheld.

[122] “Burkina Faso suspends French broadcaster RFI,” RFI, December 3, 2022.

[123] Benjamin Roger, “Exclusif – Burkina Faso : le voyage secret du Premier ministre à Moscou,” Jeune Afrique, December 10, 2022.

[124] Sam Mednick, “Russian role in Burkina Faso crisis comes under scrutiny,” Associated Press, October 18, 2022.

[125] Caulcutt.

[126] Jason Burke, “ Burkina Faso coup fuels fears of growing Russian mercenary presence in Sahel,” Guardian, October 3, 2022.

[127] Wassim Nasr, “Burkina Faso coup leader taps anti-French sentiment for support for putsch,” France24, October 2, 2022.

[128] David Gormezano, “Barkhane, Takuba, Sabre: French and European military missions in the Sahel,” France24, February 16, 2022.

[129] “La France n’écarte pas un retrait de ses forces spéciales du Burkina Faso,” RFI, November 21, 2022.

[130] Author interview; identity, name, and date withheld.

[131] Jules Duhamel, “Activity of jihadist militant groups in Burkina Faso, 2022,” Jules Duhamel website, December 7, 2022.

[132] “Togo Repels ‘Terrorist’ Attack: Official,” Defense Post, August 23, 2022.

[133] For more on the jihadi threat dynamics in Benin, see Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, “Jihadists operating out of parks and reserves have displaced civilian authorities and eliminated …,” Twitter, October 17, 2022.

[134] Leif Brottem, “Jihad Takes Root in Northern Benin,” ACLED, September 23, 2022.

[135] Wassim Nasr, “#Mali encore plus à l’ouest, le #JNIM #AQMI revendique l’attaque de #Yélimani #Kayes …,” Twitter, December 2, 2022.

[136] Author interview, Malian source; identity, name, and date withheld.

[137] For more the international contributions to MINUSMA, see https://minusma.unmissions.org/en/personnel

[138] “Mali : les Allemands de la Minusma suspendent leur opération de reconnaissance,” Jeune Afrique, September 20, 2022.

[139] Frank Specht, “Mali-Einsatz der Bundeswehr steht vor dem Ende,” Handelsblatt, November 22, 2022.

[140] Michael Fitzpatrick, “Côte d’Ivoire to pull peacekeepers out of Mali by August 2023,” RFI, November 15, 2022; “UK announces withdrawal from Mali,” Africa News, November 15, 2022; “Dernières opérations du contingent suédois de la MINUSMA avant sa fin de mission,” United Nations Peacekeeping, December 9, 2022; “U.N. says Benin will terminate contribution to peacekeeping mission in Mali,” Reuters, May 19, 2022.

[141] See MINUSMA’s reports, available on its website.

[142] “Annual Threat Assessment to the Homeland, Statement for the Record, Ms. Christine Abizaid, Director, National Counterterrorism Center,” United States Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs, November 17, 2022.

[143] Serwat, Nsaibia, Carbone, and Lay.