“All we seek is a safe place, but unfortunately we found ourselves in another war.”

Thousands of Eritrean and Sudanese refugees are demanding to be relocated from unsafe camps in Ethiopia’s conflict-hit Amhara region, where they say they lack basic services and are subject to almost daily attacks from local militiamen and armed bandits.

Amhara, Ethiopia’s second-most populous region, has since August 2023 been gripped by a full-blown rebellion, pitting a loosely organised constellation of ethno-nationalist militia groups called Fano against government forces. With the Fano claiming they control 80% of Amhara, most of the region has tipped into lawlessness.

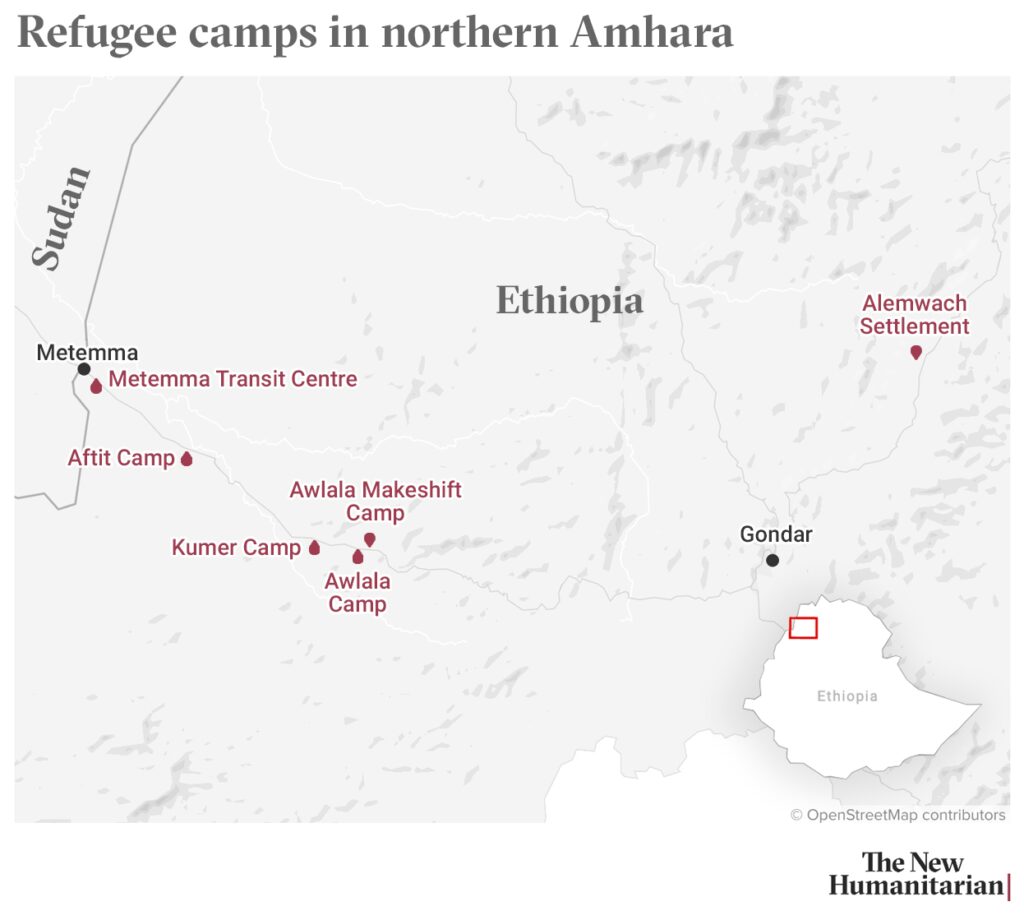

Eritrean refugees at Alemwach camp in Amhara’s North Gondar Zone told The New Humanitarian they face constant robberies, kidnappings, and physical attacks from local armed men who regularly come into the camp, which is administered by the UN’s refugee agency (UNHCR) and Ethiopia’s Refugees and Returnees Service (RRS).

Some refugees at the site have been shot, while others have been stabbed by armed men who steal mobile phones, cash, and other items. At least nine refugees have been killed at Alemwach in the past year, according to a tally by the camp’s leadership committee.

At two other camps in Gondar – Kumer and Awlala – which were shut down earlier this year because of insecurity, Sudanese refugees described similar attacks, and being made to perform forced labour by host communities.

“There is no protection at all for the refugees”

“Every week, there are gunshots,” an Alemwach resident told The New Humanitarian. Like others, he requested anonymity for fear of reprisals. Armed men “come and steal materials nearly every day”, he said. “There is no protection at all for the refugees.”

A Sudanese refugee previously at Awlala camp said: “In the evening, armed people would come inside the camp and start robbing people, taking their cell phones. There were a lot of attacks.” A Sudanese former resident of Kumer camp said: “Kidnapping, robbing and threatening the refugees is very, very normal. It’s not rare at all.”

Alemwach, which hosts up to 21,000 refugees, was set up after four other camps for Eritrean refugees in the next-door Tigray region were destroyed during the 2020-2022 northern Ethiopia war, which according to some estimates killed as many as 600,000 people.

During that conflict, Eritrean refugees came under attack from both sides – by rebel Tigrayan militia groups and by Eritrean soldiers allied with Ethiopia’s federal military. Hundreds, possibly thousands, were forcibly repatriated to Eritrea and conscripted into the army.

Alemwach, established in 2021, was supposed to offer a safe haven for Eritrean refugees. In February this year, UNHCR’s country director, Andrew Mbogori, described it as “an example of refugees living side by side with host communities”.

But camp residents told The New Humanitarian that attacks by locals started almost immediately after they arrived, with the frequency increasing after the Fano rebellion broke out in mid-2023.

“In this area, nearly every member of the host community has a gun in their house,” said another refugee. “They come into the camp in groups at night.” He added: “The host community is very aggressive. They don’t accept the refugees to live there.”

A member of the refugee leadership committee at Alemwach said refugees had expressed concerns about security at the site in meetings with UNHCR and RSS before the camp was established, but he claimed these were ignored.

Ethiopia is home to over one million refugees, making it the second-largest host country in Africa. Among those seeking shelter are around 50,000 people who have fled the civil war in Sudan that erupted in April 2023.

The Kumer and Awlala camps – which shelter predominantly Sudanese refugees – were closed earlier this year because of the insecurity and thousands of people were relocated to a new camp, Aftit, which can host up to 12,000 people. A resident said security is better at Aftit but there are few services.

“All we seek is a safe place, but unfortunately we found ourselves in another war,” said another Sudanese refugee in Amhara.

In a statement, UNHCR said it was providing healthcare, water and other services to residents of Alemwach camp, as well as essential items. The agency said efforts were underway to set up “essential services” including food, water and shelter at Aftit, which it described as “a safe place”.

It added it had “long advocated with regional authorities to further strengthen security around the sites to ensure the safety of refugees” and that additional security personnel were deployed to Alemwach last week. “UNHCR continues to advocate with the government of Ethiopia for the relocation of refugees to safer locations in another region,” the statement said.*

Last month, Human Rights Watch said it had reviewed a list provided by Sudanese refugees describing 347 incidents of forced labour in 2023 and 2024 at the Kumer and Awlala camps, including agricultural work. The rights group has also documented killings of refugees by locals, and instances of Sudanese refugees being beaten and pushed back across the Sudanese border by Ethiopian security forces.

“Sudanese refugees in Ethiopia have been targets of abuses for more than a year from various armed actors,” said Laetitia Bader, deputy Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “These refugees have fled horrific abuses back home and urgently need protection, not further threats to their lives.”

The impact of insecurity on aid access

The conflict in Amhara has precipitated a general breakdown of law and order across the region, paralysing the local economy. With government forces and police mostly restricted to towns, armed actors have moved to exploit the security vacuum in the countryside, where robberies and kidnapping for ransom are now rife.

Sudanese and Eritrean refugees described their attackers as armed members of the local host community who are taking advantage of the breakdown of law and order for financial gain, as well as elements of the Fano militia groups fighting the government.

“In this area, the police have no power,” said an Eritrean refugee, who like others interviewed, asked not to be named for security reasons.

He added that the government had posted local militiamen to guard the Alemwach camp, but these men also prey on the refugees. “Sometimes they protect us, sometimes they let the bandits in to do what they want, and sometimes they also rob us,” he said.

Another Eritrean refugee said four men with guns and knives recently robbed him as he returned from praying at a mosque after dark. Afterwards, the men raided three tents inside the camp. “This happens almost every day,” he said. “There is no security at all.”

Kidnapping is an additional problem. At Alemwach, seven children and five adult refugees have been abducted in the last year by armed men for ransoms of up to 500,000 Ethiopian birr ($4,116), according to the camp’s leaders. Other Eritrean refugees have been held hostage for smaller amounts.

The insecurity means aid groups are struggling to deliver services across Amhara, where millions need aid. Most of the region is classified as “hard to reach” or “partially accessible” on UN access maps. So far this year, at least six aid workers have been killed in Amhara. Others have been kidnapped and robbed by armed men.

“Ambulances are too scared to come, so we have to carry people to the nearest hospital on stretchers. If you are seriously sick, there is no help at all.”These access issues have hit Alemwach and Aftit, which residents said lack basic services. Latrines are full or have been swept away in flooding, forcing people to defecate in the open. Health services are limited, and basic medicines are unavailable. Many residents haven’t received blankets and other necessities. At Alemwach, food deliveries are irregular and rations have been slashed by more than 50%, residents said.

“Ambulances are too scared to come, so we have to carry people to the nearest hospital on stretchers,” said a resident of Alemwach. “If you are seriously sick, there is no help at all.”

In May, more than 1,000 refugees left the Kumer and Awlala camps in protest at the insecurity. They intended to travel to Gondar, the main local town, but were blocked by police. The refugees refused to return to the camps and instead sought shelter in a forest where they were subjected to further attacks. Several went on hunger strike.

Residents of Alemwach described similar restrictions on their movements, with local security forces preventing them from leaving the camp unless they paid bribes of up to 40,000 Ethiopian birr ($330). “If you don’t pay, they turn you back,” said an Eritrean refugee. “It’s a prison, not a camp.”

In recent weeks, fighting between the Fano and Ethiopia’s federal military has erupted around Alemwach and a UN transit camp for Sudanese refugees at Metema on the Sudanese border.

Eritrean refugees at Alemwach are asking to be moved to a new, safe location. In a letter sent to UNHCR on 6 October, refugee leaders said: “Currently, there is no authority responsible for protecting or ensuring the safety of refugees at our site. The surrounding area is a high-conflict zone, and the lives of refugees are in grave danger.”

The demand echoes calls by Sudanese refugees in Amhara. “The whole region is on fire,” a Sudanese refugee in Gondar told The New Humanitarian. “We cannot live in this place. We are asking to be taken out and put in a safe place, with full rights and protection.”