The African continent saw a significant increase in coups in the last three years, with military figures carrying out takeovers in Gabon, Niger, Burkina Faso, Sudan, Guinea, Chad and Mali.

After Niger’s coup in July, the regional Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) said it would not tolerate another takeover, and implemented tough sanctions and threatened military action to restore that country’s democratically elected government.

“The decision is that the coup in Niger is one coup too many for the region, and we are putting a stop to it at this time. We are drawing the line in the sand,” said Abdel-Fatau Musah, the bloc’s commissioner for political affairs and security.

Despite the unified response from most West African nations, Niger’s junta remains in power, demonstrating the difficulty of reversing a coup once it has taken place.

United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres spoke of “an epidemic” of coups after Sudan’s in October 2021, a year in which there were four successful government overthrows in Africa and one in Myanmar. He described an “environment in which some military leaders feel they have total impunity” and “can do whatever they want because nothing will happen to them.

Before the recent spate of putsches, coups in Africa had been declining for much of the past two decades. In the 10 years before 2021, there had been on average less than one successful coup per year, according to U.S. researchers Jonathan Powell, formerly at the University of Central Florida, and Clayton Thyne at the University of Kentucky, who consolidated their findings on their Arrested Dictatorship website.

The latest power grabs in Africa have raised concerns that the region could be backsliding from its progress toward greater democracy.

Compared to the world

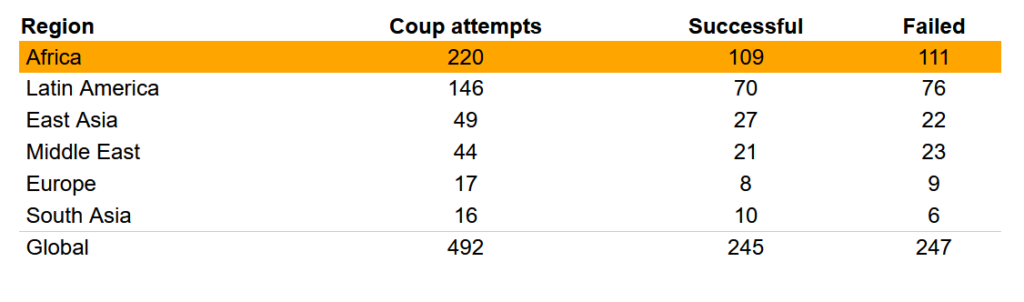

Of 492 attempted or successful coups carried out around the world since 1950, Africa has seen 220, the most of any region, with 109 of them successful, Powell and Thyne’s data show.

Powell told VOA this is because Africa tends to have many of the conditions that are normally associated with coups.

“Coups have become increasingly limited to the poorest countries in the world, and the recent wave of coups fits into that,” he said.

Gabon, Niger, Burkina Faso, Guinea, Chad and Mali all had less than $22 billion in GDP in 2022, according to a World Bank estimate, while Sudan had a GDP of $52 billion. By comparison, the United States’ GDP was worth $25 trillion in 2022, ranking it the highest in the world.

Countries experiencing ongoing terrorism campaigns and insurgency are also disproportionately more likely to see coups, according to Powell, as well as those nations whose leaders lack legitimacy in the eyes of their citizens or armed forces.

Powell said that while most of Africa no longer see coups as a threat, the Sahel region, which includes Niger, Burkina Faso, Mali, Chad and Sudan, still experience many of the most common factors that lead to coups. He said Niger’s “background characteristics and geography are exactly what we would have expected if we were trying to predict” where the next coup would be located.

Leaders of the Niger coup, as well as those who took over the government in Burkina Faso in September 2022, cited their governments’ failure to stem a deadly Islamist insurgency in the Sahel as part of the justification for their takeovers.

African nations

Out of 54 countries on the African continent, 45 have had at least one coup attempt since 1950, according to data collected by Powell and Thyne. Narrowing the focus to only those countries that have experienced a successful takeover — one in which perpetrators hold power for at least seven days — that number drops to 37, or about two-thirds of nations on the continent.

What is a coup?

A coup is an “illegal and overt attempt by the military or other elites within the state apparatus to unseat the sitting executive,” Powell and Thyne wrote in a 2011 article published in the Journal of Peace Research. A successful coup, they determined, lasts at least one week.

According to this definition, the target of a coup must be a sitting executive, and the perpetrators must have formal ties to the national government. Movements that attempt to overthrow an entire government and which are led by those not connected to power, such as rebellions or mass protests, are not included.

While some definitions of coups limit the perpetrators to only military figures, Powell and Thyne said doing so would likely bias the data toward successful coups.

“The initial instigation of a coup attempt frequently involves civilian members of the government alone, with the military playing a later role in deciding whether the putsch will be successful,” the researchers wrote. They cite the example of a 1962 coup attempt led by Senegalese Prime Minister Mamadou Dia that failed because he was unable to gain the military’s support.

Coup perpetrators must also be “within the state apparatus,” which excludes takeovers largely directed by foreign governments. Powell and Thyne cite the example of the fall of Ugandan President Idi Amin in 1979 at the hands of the Tanzanian military, saying the action “does not constitute a coup because foreign powers were the primary actors.”

Countries with the most coups

Sudan tops the list as the African country with the most coups — attempted and successful — since 1950, with 18, Powell and Thyne’s data show. Of those takeover efforts, six were successful, including one in October 2021. An attack on Sudan’s military in April by paramilitary forces — classified by the data as an attempted coup — has led to months of fighting between the two military factions.

While Burkina Faso has had fewer total coup attempts in the same period, it has the highest number of successful coups, with nine, including two in 2022. In addition to the most recent putsches, coups were successfully carried out in Burkina Faso in 1966, 1974, 1980, 1982, 1983, 1987 and 2014. A coup was also attempted in 2015.

Nigeria, Africa’s most populous nation, had a long history of coups following independence in 1960, with eight coup attempts — six of them successful. However, since 1999, the country has transferred power through democratic elections and helped usher in greater stability in West Africa and the continent as a whole.

Coups per country since 1950

What factors lead to coups?

The African Union Peace and Security Council said in 2014 that unconstitutional changes of government often originate from “deficiencies in governance” along with “greed, selfishness, mismanagement of diversity, mismanagement of opportunity, marginalization, abuse of human rights, refusal to accept electoral defeat, manipulation of constitution[s], as well as unconstitutional review of constitution[s] to serve narrow interests and corruption.”

U.S. researchers Aaron Belkin and Evan Schofer have found that the strength of a country’s civil society, the legitimacy conferred on a government by its population, and a nation’s coup history are strong predictors of coups.

Powell told VOA that a recent coup can “signal a breakdown of politics-as-usual, a change in power dynamics that prompts future counter-coups” as a result of rivalries within the army. He said that some countries fall into what is known as a “coup trap,” in which a large number of coups can occur in quick succession. An example is Mali, where four coup attempts took place in the past decade after the country did not experience any in the prior 20 years.

Mali’s 2020 coup leader Assimi Goita cited widespread popular dissatisfaction toward those in power when he seized control. However, when he carried out a coup less than a year later in May 2021, overthrowing a transitional government that he helped set up, he cited a Cabinet reshuffle that excluded two key military leaders. Goita claimed the move violated the terms of the new government. French President Emmanuel Macron called the action “a coup within a coup.”

In Gabon, military leaders carried out an August coup after elections that were set to extend the rule of the Bongo family, who had led the country for more than five decades. Coup leaders accused President Ali Bongo Ondimba, who came to power after the death of his father, of irresponsible governance. While the international community denounced the coup, some officials also criticized a lack of transparency in Gabon’s election system.

“Naturally, military coups are not the solution, but we must not forget that in Gabon, there had been elections full of irregularities,” said Josep Borrell, the European Union’s foreign policy chief.

In Guinea, coup leaders said concerns about corruption and a failing economy motivated their takeover in September 2021, as well as the fact that deposed President Alpha Conde had been serving a third term after changing the constitution to allow it.

Countries that are poorer and whose democracies are less stable have historically been more prone to takeovers. Fifteen of the 20 countries topping the 2022 Fragile States Index created by the Fund for Peace are in Africa. Of those, 12 have had at least one successful coup in their history. They include Somalia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic, Chad, Sudan and Zimbabwe. Conversely, there have been no successful coups in richer African countries with strong institutions, such as South Africa and Botswana.

Coup success rate

Powell and Thyne’s research shows that coup attempts in the past decade have had a far higher success rate than those of previous decades. So, while coups are becoming less frequent around the world, they are also becoming more effective.

The greatest number of successful coups in Africa took place near the midpoint of the U.S.-Soviet Cold War rivalry stretching from 1946 to 1991. Coups were most prevalent in 1966, when seven took place. The next most tumultuous year was 1980, when five were staged.

“During the Cold War in particular, there was effectively an unwritten rule saying if you controlled the capital, you were recognized as legitimate,” said Powell. Following that time, and especially since 2000, he said the international community has been far less tolerant of coups. As a result, coup leaders are more likely to wait for circumstances in which the “status quo itself is terrible,” or when they feel they can survive any negative responses to a coup, including sanctions.

A look ahead

In 2021, the U.N.’s Guterres cited three main reasons for the recent increase in coups: strong geopolitical divides between nations; the COVID-19 pandemic’s economic and social impact on countries; and finally, the U.N. Security Council’s inability to take strong measures in response to coups. For instance, Russia and China, both veto-holding members of the council, in late 2021 blocked it from imposing fresh sanctions on Mali’s coup leaders after those leaders announced delays in elections that would return the West African country to civilian rule.

The COVID-19 pandemic not only negatively affected countries most prone to coups by straining already tight budgets and placing further restrictions on populations already skeptical of their government, it also impacted world powers, which often take actions to help prevent coups. However, now that the pandemic has ended, the high number of attempts to overthrow governments has not abated.

In response to the July coup in Niger, ECOWAS mounted a strong response that might have been difficult during the pandemic, imposing sanctions on coup leaders and threatening military action. But despite unified action, the bloc has been unable to remove the junta from power.

Powell said when the international community has been able to reverse coups in the past, it usually happens quickly — within a week or so. One of the most prominent coup reversals came in Sierra Leone following a 1997 coup, when ECOWAS was able to restore the elected government nine months later. But Powell stressed there are important differences between the two situations, including the fact that ECOWAS already had a large multinational peacekeeping force in Sierra Leone due to its civil war.

With the August coup in Gabon coming about one month after Niger’s coup, White House National Security Council spokesman John Kirby said it was too early to call the military takeovers a trend.

“It’s just too soon to do a table slap here and say, ‘Yep, we’ve got a trend here going,’ or ‘Yep, we’ve got a domino effect,’” he said.

Powell said that while it would be surprising to see such high levels of coups continuing, “I am certain the coming years will see coups in higher numbers than what we had become accustomed to.”

He added, “The underlying causes of coups are present and worsening. Until these domestic dynamics improve, or regional or global actors can provide a solution, there is no reason to think coups should go away.”