Abstract: Since 2018, the United States has been trying to figure out what counterterrorism looks like during an era of strategic competition, and how it can maximize and optimize returns from its counterterrorism investments. There are important differences between these two national security priorities—strategic competition and counterterrorism—but if the United States wants to gain resource efficiencies, it should look across the gray space at how and where these two priorities interplay and converge. This is because a key part of the pathway to CT optimization lies in realizing how counterterrorism has evolved as a form of influence. This article introduces a conceptual framework to help the counterterrorism community situate the returns from CT investments, especially deployed CT force activity. It recommends that those returns be understood through two lenses: 1) those that are direct and oriented around threat mitigation and 2) those that are intersectional and oriented around influence. Interviews with three experts provide context to elements of the framework and highlight the interplay between counterterrorism and strategic competition in different regional areas.

The day after al-Qa`ida’s surprise attack on 9/11 was the beginning of a new era for the United States. It usually takes time for the U.S. national security apparatus to pivot—the analogy that is often used to describe this process is the turning ability of an aircraft carrier, which can only make movements in a slow and deliberate manner due to its size. But on September 12, 2001, the United States made an immediate and hard shift in its priorities, and for a considerable period, it did not look back. During those early days, it was as if resources did not matter. As outlined by Eliot Ackerman: “At a joint session of Congress on September 20, 2001, U.S. President George W. Bush announced a new type of war, a ‘war on terror.’ He laid out its terms: ‘We will direct every resource at our command-every means of diplomacy, every tool of intelligence, every instrument of law enforcement, every financial influence, and every necessary weapon of war-to the disruption and to the defeat of the global terror network.’”1 For a period, time mattered little as well, as the 2002 U.S. National Security strategy outlined the war on terror as being “of uncertain duration.”2

That environment is long gone, and for good reason. In November 2011, President Obama announced the U.S. “Pivot to Asia,”3 that kicked off a long aircraft-carrier-like turn across the U.S. government to emphasize what today it characterizes as strategic competition. The rise of the Islamic State in 2014 derailed that shift. But by 2017 when the Islamic State was on the ropes in Syria and Iraq, the United States expressed it was ready to chart “a new and very different course,”4 a course that was formalized in the 2018 U.S. National Defense Strategy, which identified “inter-state strategic competition, not terrorism” as the primary concern.5 Since that time, the United States has been slowly turning round the mechanics of government so that focus and resources align with national security priorities. To achieve that end, the United States has been working to ‘optimize’ and ‘calibrate’ its approach to counterterrorism, to prioritize terror threats more, and figure out where it is comfortable accepting risk—to figure out what counterterrorism looks like during the era of strategic competition. That has not been the easiest thing to do, as while the United States would like to spend less time and fewer resources combating terrorism, America’s terrorist adversaries are committed; they also get a vote.

As a result, over the past several years the U.S. counterterrorism enterprise has been navigating two truths and trying to find a sustainable path through them. First, the threat of terrorism is persistent. It will ebb and flow over time, but it is not going away. Second, the counterterrorism fight will no longer receive the funding or resource prioritization it once did. Adding to the challenge is that elected leaders and the American public still expect (and in many ways demand) similar CT success from a CT enterprise that is operating with fewer resources. Thus, in today’s environment, it becomes paramount that every resource spent on people, dollars, and time must go further than it has in the past—with emphasis placed on outcomes. That applies to counterterrorism and strategic competition, as well as the gray space between those two priorities.

This article introduces a conceptual framework to help the CT community frame the return on investment from counterterrorism investments, specifically those associated with deployed CT force activity. It takes a broad view, and it aims to provide insight into what those direct and intersectional returns are and how they could be considered and captured in relation to counterterrorism and strategic competition. It proceeds in two parts. Part I explains and provides context to the CT return on investment (CT ROI) framework. Part II explores the dynamics of the framework, and the interplay between counterterrorism and strategic competition, through different regional lenses and the perspectives of three specialists interviewed for this article.

Part I: Introducing the CT ROI Framework

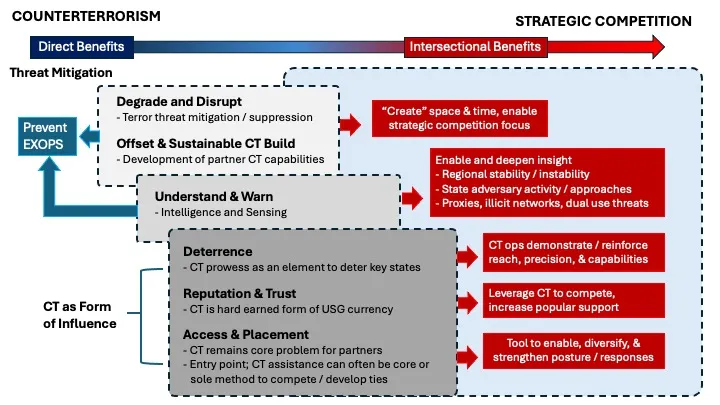

The CT ROI framework (Figure 1) is a conceptual tool designed to help decisionmakers and their staff to understand and map returns from counterterrorism investments, and to situate how those investments intersect with and can provide value to strategic competition. An overriding goal of the framework is to break down how these two national security priorities—CT and strategic competition—are often analytically bifurcated or siloed in the U.S. context and are routinely viewed, prioritized, and resourced as two distinct priorities or problems. In many ways, that line of thinking is true: CT and strategic competition could not be more different, and the tools and approaches needed to address or be effective in each can differ greatly. But there are limits to that analytical view, and in some ways, it is not helpful. This is because there are important areas where the two priorities nest and intersect. There are also areas where counterterrorism can provide key value or entry points to strategic competition pursuits. Those opportunities are not always present, but it is important to identify and maximize them when they do exist. This is especially true during an era when the two priorities present very real challenges and when the United States and its partners are trying to pursue both priorities well against committed adversaries using limited resources. From a strategic perspective, identifying areas of synergy and integration between counterterrorism and strategic competition is the smart and efficient thing to do.

The CT ROI framework has two core pillars that interplay with one another. The first is how it conceptualizes the benefits and returns from counterterrorism. This is illustrated by the arrow at the top of the graphic that moves from left to right—from direct benefits (the start of the arrow) to benefits that are progressively intersectional and that provide more relevant value to strategic competition. The second pillar is how different key goals are conceptualized in relation to the direct and intersectional benefits they provide to counterterrorism and strategic competition. These are reflected by the goal categories in gray boxes that are presented from the top to the bottom of the graphic. These include degrade and disrupt, offset and sustainable CT build, understand and warn, deterrence, reputation and trust, and access and placement.

In the United States and other contexts, counterterrorism has fundamentally been viewed as being about the mitigation of threats against the homeland and against U.S. allies and interests abroad—a mission area that uses various instruments and tradecraft to put pressure on key terror threat actors and to degrade their capabilities. When it comes to how CT returns are understood, this view dominates. That makes sense because this is the area where returns from CT investments are most direct and clear. This would include, for example, the number of mid- to senior-level Islamic State leaders removed in Syria over the past two years, other outcomes tied to unilateral or partnered direct action CT operations, or additional degrade and disrupt pursuits (i.e., financial resources seized, plots disrupted, etcetera). For the United States, the primary point of emphasis and focus of returns has been on disrupting external operations.

Partners have been critical to U.S. efforts to mitigate terror threats, and they will remain critical given the scale and persistence of the threat. For the United States, the importance and centrality of partners is reflected in the progressive emphasis that has been placed on partnerships in different U.S. counterterrorism strategies across time and administrations.6 “Build and Leverage Partner Capacity” is the second line of effort in the most recent strategic policy guidance, National Security Memorandum 13, and it notes how foreign “partnerships, already a key component of U.S. CT strategy and efforts, will take on increased importance.”7 This is because the United States views partnerships, and the development of effective and reliable partners, as a way to offset CT demands and to build a more sustainable approach to counterterrorism over time. For example, if U.S. efforts to develop the CT capacity and capability of partners are lasting, they can enhance a partner’s ability to manage terrorism problems with less U.S. involvement (or on its own), which can create additional space and time for the United States to focus less on terrorism and more on strategic competition.

The second gray box—understand and warn—focuses on intelligence and sensing activity. Intelligence enables counterterrorism activity. It also enhances the United States’ ability to understand how terrorism landscapes or specific threats are evolving, information that can be used to adjust CT priorities and to warn. But CT elements deployed in key countries also function as sensors that, by the virtue of their presence, can deepen insight into activity that is taking place in the area or region generally.a This could include, for example, the activity of state-supported proxies and illicit networks that state competitors may be leveraging or could one day weaponize, or the actions of state adversaries such as Iran.

In addition to threat mitigation, the second key value area that the framework advances is how counterterrorism can function as a form of influence. While not commonly used as a concept, this idea is not new.8 But where the framework makes a unique contribution is in how it conceptualizes deterrence, reputation and trust, and access and placement as being three areas where CT activity can play an important influence role. For example, when it comes to deterrence, U.S. CT capabilities have demonstrated operational prowess, the ability to reach, deploy force, engage in surprise, and repeatedly remove hard-to-find leaders. That type of capability “makes you feared. It makes you respected.”9

The development of the United States’ counterterrorism capabilities over the past two and half decades is a hard-earned form of currency, and the CT assistance it provides to partners is a form of currency as well.10 As noted by Matthew Levitt, “that currency buys goodwill and partnership on a wide array of other interests, including Great Power competition. The flipside is also true: if the United States declines to help other countries address their counterterrorism needs, it creates a vacuum that states like Russia and China, or Iran and Turkey, will fill.”11 Since terrorism mitigation is still a strategic priority for many of the United States’ partners—and potential partners—counterterrorism can be an entry point to develop ties and build trust, to enrich both with existing partners, and to solidify or expand U.S. access and placement in key locations around the globe.

Indeed, the authorities and plans that go into the establishment of allied and partnered CT training and operations around the world can also be key to opening the door to the access, basing, and overflight that become so critical to potential conflict between major powers. CT operations help set the logistical and legal conditions to enable future operations in key areas.

The case of the Philippines is an important example. For more than two decades, counterterrorism assistance has been the keystone of the U.S.-Philippines defense relationship. That assistance has helped to develop the CT capacity of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) and the Philippine government to mitigate key Islamist terror threats in Mindanao over time. This includes, for example, key support provided to expel regionally affiliated Islamic State elements from the city of Marawi, which the Islamic State network laid siege to for five months in 2017, and to degrade the capabilities of that network.

Building partner capacity programs have also been a key mechanism through which U.S. and Philippine special operations force elements have built shoulder-to-shoulder level bonds and trust. During the Duterte period, the U.S.-Philippines alliance was tested, and its long-term viability was questioned and put in a precarious position. At the time, the Philippine president announced his “intent to ‘separate’ Manila from Washington, and declared his desire to scrap” the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA), a key agreement reached between the two countries in 2014.12 In 2020, the Duterte administration also took steps to terminate the Visiting Forces Agreement, that helps to enable and provide protections for U.S. forces operating in the Philippines.13

The U.S.-Philippines defense relationship is largely viewed as having been a key protective element that helped the United States navigate through that period of turbulence and uncertainty. Duterte ended up reversing course, and the agreements stayed in place. In 2023, not long after the election of Philippine President Marcos, Jr. in 2022, the Philippine government expanded the number of EDCA sites in the country by four, bringing the total to nine14—a decision that has deepened U.S.-Philippine defense ties and enhanced U.S. access and placement in a strategic geographic area. Further, analysis of longitudinal polling data reveals that since 2000 Filipino trust in and satisfaction with the AFP has improved across time.15 Filipino trust in the United States has also generally remained high.16 While the Philippines case may be a unique one,17 it underlines—perhaps most clearly—the intimate interplay between counterterrorism and strategic competition pursuits, and how CT can provide different benefits to the key goals outlined in the CT ROI framework.

Benchmarks for each goal area—degrade and disrupt, offset and sustainable CT build, understand and warn, deterrence, reputation and trust, and access and placement—could be developed to enhance the practical utility of the framework, and track CT returns over time. This could take different forms. For example, terror threat mitigation efforts that are focused on key organizations in specific countries (e.g., al-Shabaab in Somalia) could evaluate the Global Terrorism Index ranking across time to identify high level changes in the threat environment. Al-Shabaab’s operational capacity; ability to command, enable, and inspire; geographic reach; operational outcomes (e.g., lethality, ratio of completed to failed attacks, etcetera.), and other metrics could also be evaluated to provide a more granular picture of the network’s temporal evolution. General and targeted survey and polling data could be leveraged to provide insights into reputation and trust. When available, this could include, for instance, data on public trust for rebel movements, armed groups, and terror networks in specific countries, with emphasis placed on whether that trust is improving or declining. Data that provides insight into public support and trust for partner security forces, CT campaigns, partner force trust in the United States, or country-level trust in the United States or the U.S. military could be leveraged in a similar way.

Part II: CT and Strategic Competition – Regional Views

The section explores the dynamics of the framework, and the interplay between counterterrorism and strategic competition, through different regional lens and the perspectives of three specialists who were interviewed for this article. These three individuals, and their areas of focus, include Christopher Faulkner (Africa), Michael Knights (Middle East, with emphasis placed on Iraq, Syria, and Yemen), and Magnus Ranstorp (Europe). The views shared by these experts help draw attention to key case studies, how CT and strategic competition dynamics manifest in different regions and where there are areas of commonality and divergence, and other issues, including challenges and opportunities, that are important to consider.

Africa – Christopher Faulkner

CT as Threat Mitigation in the African Context

I think how the United States views counterterrorism in the African context is still very much through the lens of threat mitigation—e.g., number of attacks thwarted, assessing the severity of attacks, considering if the location of attacks is spreading or becoming more concentrated, etcetera. Those things still very much matter, but—and this sounds cliché—an overreliance on traditional metrics of threat mitigation can miss the forest for the trees. To overgeneralize a bit, the United States should probably view CT in the African context through the theme of resilience—security force resilience, community resilience, regional cooperation (like regional economic communities or security architectures) resilience.

For African states, there is still a need to count traditional [threat mitigation] metrics, especially in locations where terrorism is thriving (i.e., the Sahel). But it is as important, if not more important, to think about a much broader spectrum of factors to gauge CT value/benefits. African states, in partnership with U.S. and European partners, would be wise to focus on assessing metrics more closely linked to the root causes of terrorism (e.g., poverty, lack of educational opportunities, poor governance, corruption, etcetera), which can lead to a more durable and comprehensive CT approach. Many groups exploit these conditions, tapping into personal agitation or financial stability as [a] means to recruit.

Another element African states might look to is regional security cooperation: number of troops trained, number of joint exercises, etcetera. These efforts are short of things like kinetic targeting but speak to security cooperation, interoperability, coordination, and resilience that can be important for mitigating enduring threats.

Lastly, community policing and engagement need to improve. I’m reminded of a blog post which reported on trust in police in Africa,18 and the moral of the story is that trust in police is quite poor in many states. So, working to improve community policing, trust in police, and working with local leaders and community leaders can be critical for successful CT efforts.

CT’s Relevance, or Irrelevance, to Strategic Competition in Africa

I think there are two schools of thought here. First is the idea that CT is directly relevant to strategic competition because it is ‘in demand’ by a number of African states and a necessary way to compete with strategic competitors like Russia who has emerged as an alternative security partner.

The second thought is that CT is irrelevant, or at least should be, because it treats African states as pawns in a competition between the United States and Russia. In other words, it runs the risks of failing to consider the agency of African partners because of the tunnel vision of competing with Russia—seeing CT as a way to ‘beat’ Russia and not as a means to support African partners. Some analysts have really equated the current environment as posing a strategic “trilemma,” with the United States trying to balance “promoting democracy, combatting violent extremism, and engaging in great-power competition.”19 Though I’m cautious in suggesting a policy of democracy promotion, pushing it aside in favor of the latter two lines of effort can unintentionally undermine the United States over the long term.

Some of this might seem like semantics, but I think it matters. My take, as I’ve written elsewhere, is that CT has relevance to strategic competition and can be a valuable tool for the United States, but it must be a more comprehensive project, focused not exclusively on military means but instead on prioritizing non-military instruments of national power that can genuinely differentiate the United States from its strategic competitors like Russia, [which] is primarily focused on using the barrel of a gun, or China, [which] is primarily interested in economic/infrastructure investment which often comes off as predatory.

Another element that I think is important to keep in mind is that almost all critiques of the U.S. approach to CT in the Sahel and across Africa writ large is that even interagency programs can come off as overly militaristic because AFRICOM becomes a primary driver simply because it is better resourced than its interagency partners. Moreover, it isn’t inherently true that African security forces lack capacity to combat terrorism, but there are serious governance challenges that can put the United States in a position where it is seen as reinforcing a corrupt government. Chad comes to mind as a case where U.S. pragmatism in not branding a coup a coup can be seen as delegitimizing for the United States by other African states.

The U.S. exit from Niger and pursuit of relationships with coastal West African states is an example where CT/strategic competition priorities intersect and the United States must be careful to marry traditional CT efforts (security force assistance and CT training/investment) with diplomatic investment, economic investment, promoting healthy democratic norms like respect for the rule of law, media freedom, electoral norms, and investing in civil society. The Biden administration’s $100 million pledge in March 2023 for several littoral West African nations, including Benin, Ghana, Guinea, Cote d’Ivoire, and Togo,20 was specifically designed to invest in stopping the spread of terrorism from the Sahel, but in implementation, it needs to have a whole-of-government approach to include DoD, State, USAID, Commerce, and so on.

Is CT as a Form of Influence a Useful Concept in the African Context?

Yes and no. There is a double-edged sword here. CT activity/assistance is arguably necessary as a means of yielding influence, especially because the trajectory of terrorism demands CT assistance. But the risk is that such provisions, in isolation, rarely if ever resolve the insecurity and then can unintentionally help contribute to anti-Western sentiment. As a result, the United States risks running afoul by using CT activity/assistance as a means of doing ‘great power’ or ‘strategic competition’ without considering the agency of African partners.

It’s a truism that post-2001, the United States dramatically scaled up its CT operations globally, and one could argue that CT became a primary means of guiding U.S. strategy in Africa. In short, while there were some clear successes in CT as a form of influence to generate partnerships with African militaries, leading with CT, or rather doing it in isolation, is not a durable long-term strategy.

Still, the United States cannot abandon CT support as a form of influence in Africa. It might be limited on where it can do certain things, but simply withdrawing CT as a means for influence would only be playing into the hands of Moscow. How we do CT and putting African governments at the helm of crafting ideas and solutions for CT can be powerful for identifying long-term strategies. In other words, giving African states agency is going to be critical and necessary for long-term buy in. The United States can advise and guide, but enduring CT efforts are going to have to be organically developed and implemented (within reason). My two cents is that local actors are far better positioned to think through enduring solutions for local communities.

Strengths and Weaknesses of the CT ROI Framework

I think the framework has a lot of value, especially in suggesting that CT ‘intersects’ with strategic competition rather than framing CT as a way to ‘do’ strategic competition.

The overarching thing I like about the framework is that it’s really about capacity building broadly construed. The three strongest pieces to me are the CT Build (top left box), the reputation/trust bullet, and the access/placement bullet.

On CT Build: It’s going to remain necessary to build partner capacity so that the United States is helping African partners develop a comprehensive CT ecosystem both at the national levels and at the regional level.

On Reputation/Trust: CT can clearly be a way to build trust, but it can also be a way to lose it. Working with African militaries/police can build trust between these institutions and the United States, but it’s important to consider the relationship between the military/police and local populations as training units that are widely unpopular or distrusted by local populations can be self-defeating.

On Access/Placement: I think this is a really strong point. CT as an ‘entry point’ is critical—maybe necessary in some cases— but it also needs to be complemented. For example, traditional ways of thinking about CT (kinetic approaches, security force assistance, etcetera) is that this is something the United States does well and it is in demand. So, the U.S. should not sacrifice its comparative advantage, but it should also do so in tandem with interagency investment to ensure it’s attacking the immediate problem (terrorist threats) and the enduring problems (development, corruption, etcetera) that contribute to terrorism.

Middle East – Michael Knights

CT’s Relevance, or Irrelevance, to Strategic Competition in the Middle East

The first thing is, who’s the first world leader to call [President] George Bush and commiserate with him after 9/11? [Then Yemeni President] Ali Abdullah Saleh. He immediately recognized that it was going to be a huge boon to him potentially. So, one thing to point out is that there’s a demand for our CT support.

It is important that we try and make sure we don’t get suckered in that process because a lot of people will want our CT support in order to kill domestic opponents, to create death squads, and all that kind of stuff. But in great power competition, it is also important to strengthen partners.

Any kind of special forces and intelligence interaction with the partner, whether you call it CT or something else, is very intimate, very highly valued. For Ali Abdullah Saleh, from the first minute after 9/11, this was the future for him. It didn’t actually end up working very well for him eventually. He saw us as an absolute goldmine, and when a partner country sees you as a gold mine, that’s not a bad thing. That’s a good thing.

China can talk a big fight when it comes to being a peer competitor to us. It can certainly provide very useful repression tools. But when it comes to actually hunting down terrorists, the U.S. brand is unrivaled and will probably remain unrivaled for a very long period of time.

A lot of people doubt our strategic acumen. They doubt our level of attention to their concerns. But they never doubt our ability to find, fix, and finish someone or something on the surface of the earth or under the surface now.

In terms of brand and competitive advantage and unique selling point, we are head and shoulders above anybody else. Everyone knows that we can do this stuff. That’s very important in great power competition, to have a unique capability that everyone knows nobody else has really got. It makes you feared. It makes you respected. It makes you a fantastic partner to have if you’re the Iraqis trying to root out ISIS. We’re a must-have partner.

In 2014, the Obama administration basically said [to the Iraqi government], ‘If you want our CT help, you’re going to get rid of that guy [Prime Minister] Nouri al-Maliki, who in our view is counterproductive.’ That’s an interesting case study. In the battle of Tikrit in 2015, the Iraqi military said, ‘If we have to choose between the Popular Mobilization Forces supported by Iran and the U.S.-led coalition, we’re gonna choose the U.S.-led coalition.’

Likewise, when the Russians, Syrians, and Iranians opened the Quadrilateral Command Control Center in Iraq in 2015, we knew very quickly that it was just hollow, and [the] Iraqis knew very quickly it was hollow. It couldn’t do anything. They brought a bunch of geriatric Russian generals in; there was no technical capability. There was nothing like our [setup].

So, whether it’s a technical system, whether it’s an entire find, fix, finish system, or whether it’s the U.S. Marine Colonel who is in the Joint Operations Center – Iraq quarterbacking the Battle of Ramadi, that kind of support is extremely valuable.

I could keep talking and throw up bazillion ways that counterterrorism support gave us a seat at the table we otherwise wouldn’t have had in Iraq, in Yemen.

Counterterrorism and Deterrence in Relation to Iran

First of all, anytime U.S. forces occupy a space, anytime we’re in an environment, it makes it harder for Iran or Russia to be in that same environment physically, for instance, to cohabitate key headquarters. And that’s important: As long as we’re there, they’re not there.

As bad as things are in Iraq, there’s not going to be a Revolutionary Guard Quds Force tactical operations center in the prime minister’s office in Iraq, purely because it’s us or them when it comes to facility presence, and that’s important I think. So, we deny space by continuing to operate in space.

When we removed the task force etcetera, from al-Anad in Yemen as the south of the country was falling in 2015, we lost a lot of interaction. We lost what could have remained in place. Not there, but it could have remained in place somewhere in Yemen essentially as our alternate and shadow embassy on the ground and a source of collection of all kinds of intelligence, including diplomatic intelligence.

So, if you look at how the [United Arab] Emirates used their special forces, which is a counterterrorism capability, they used it to essentially fill the gap while their diplomats were not there for a number of years.

We’ve done that, for instance, in northeastern Syria, too. If you look at it, that is not really the way it should be done, but it becomes—in a war environment—the next best thing to having an embassy or a consulate in place.

It is space filling. It’s the same in Iraq right now. I mean, as we close down al-Assad perhaps, in the west of the country, one whole portion of the Iraqi population (i.e., the Sunnis) will say, ‘We now have no direct contact with the Americans anymore.’

If we would have closed down our counterterrorism ops in northern Iraq, Kurdistan Region of Iraq, same thing would happen. If we do it in Syria, same thing. It creates a sense of abandonment. And who fills that? Obviously, the other side fills it. Wherever we leave, you can see they do vacuum-filling. Any of our opponents, the Russians and the Iranians, do vacuum-filling. [The] Chinese are a little bit different.

Let me [also] just say this on deterrence. A determined enemy will try and penetrate an environment, and I’ll talk about here about the Iranians in Iraq. They will try and penetrate the environment because it really is a strategic priority for them. They are slightly deterred from taking certain actions due to the presence of our special operations and the importance the Iraqis place on having them remain in position, but it doesn’t deter completely. They’ll just work ways around it. They move slower essentially.

So, for instance, the way they’ve undermined the CTS [Iraq’s Counter Terrorism Service], the way they’ve essentially done a very, very, very slow rolling coup in the country. It never hit the point where we recognized something urgently dangerous enough for us to turn to the Iraqis and say, ‘Your CTS was surrounded, our advisors, we’re ready to help you go remove these guys from the government district.’ They’ve worked around us over time. We didn’t deter them with our special force presence, but there’s probably many acts that we are deterring with the Iranians by being at Al-Asad, let’s say

Now, if we give up that presence, which we probably will, what the U.S. government often doesn’t realize is that just by being there, U.S. forces are stopping worse things from happening. They look at a placement, and they say, ‘It doesn’t seem to be having any effect.’ But what it’s doing is to put a floor on how bad things can get once it’s gone.

Without the CT mission, there is no floor anymore. Whether its central African coups falling into Wagner, whether it’s the way Iraq deteriorated 2011 through ‘14. Of course, we did have a CT presence there, but it just wasn’t integrated with anything else.

That’s a good example of a deterrence failure. We maintained our training presence with CTS in 2011, 2012 through 2014. It didn’t prevent either the major penetration by the Iranians or the return of ISIS. There’s something about that experience that should have worked better but didn’t.

I think one of the reasons for it is probably because we powered down too much. In 2013, the Iraqis were saying, al-Maliki was saying, ‘Please come back and drone strike. Drone strike in Anbar. Drone strike around Sinjar, please. Either give us Apaches, give U.S. drone strikes. Help more than you are right now. Get more active. Actually, get kinetic again. And we’ll make it happen permissions-wise.’ And we didn’t do it. As a result, I think we missed a trick there. So, you could say it’s a case study of failure, but that’s probably because we ourselves didn’t see the need to get a bit more muscular.

What’s the point of us being in Iraq or Syria, Iraq particularly? It’s very depressing because for the USA, a decisive strategic culture that likes to win, that likes to fight conflicts and then go home. The very Jominian decisive kind of warfare type model.21 The reality is it’s horrible for the serving members who are out there, that it’s not necessarily that they’re contributing much. But their absence will cause significant deterioration. So, we are holding a space, and we hate to hold a space and not decisively win or change things while we’re there. But there is an important value to holding a space, and conventional forces don’t cut it in that environment. CT is what’s still important, and it always will be.

CT as a Form of Influence

First of all, when you got a good product and you do have a good product, when it comes to CT support, you have to make maximum use of that in strategic competition.

Sometimes it can feel a little distasteful, particularly to the diplomats. For instance, what is America good for—killing your enemies, killing your Sunni jihadis in Iraq, let’s say. We are those guys you bring in to help you dig people out from under rocks and kill them.

For diplomats there, if you listen to the way they’re framing it in Iraq, they’re saying, ‘We want a 360-degree relationship with Iraq. It’s not just about military.’ And the Iraqis are like, ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah, but does the CT still come?’ You know, they’re trying to sell them something that we’re crap at, which is investing in their country. We’re not gonna do that. You know all this stuff that State and the broader machine wants to sell, but the reality is what they want is our CT. That’s a reality that we will be unwise to not recognize. We are good at finding [and] killing people, and it’s something we’re known for worldwide. We might want to be more than that, but it’s one of the only things we do that works properly when we try and export it, and some of our military hardware, too, but some of that’s too complicated and we don’t want to release it. It’s more than they need.

To me, when I look at us being able to mentor the special forces of countries around the world, what I’m looking at [is] us being able to basically develop the countercoup force in that country.

Supporting CT forces is vital because such elite military leadership tends to move sideways into the conventional leadership structure.

So, CTS—that was the effort in Iraq—this was the force that might prevent a militia takeover or Iranian takeover. This was the force that, under the worst circumstances, might hold civilian government open in a guarded military role. This is the force that we could always count on to protect our technology and our training.

Now, unfortunately, it’s going wrong as we speak. It has been allowed to atrophy and to be politicized, and the best example of what we will try to do with CT is starting to fall apart, sadly, in Iraq. It’s a good case study of what you must not let happen.

So, I am not suggesting we need School of the Americas 2, but I am suggesting that special forces leadership tends to become very significant leadership within the country. And they provide a safety catch, and they provide an ultimate force for cooperation. Or where a government has gone badly wrong, they provide an ability to fix the problem and restore some kind of system of government that works. So, they’re critical to have. Look at all these coups in central Africa.

Europe – Magnus Ranstorp

CT as Threat Mitigation in the European Context

Maybe the best example is the U.K. one, which has become sort of standard all across Europe, and that is, if you look at the four ‘P’s—prevent, pursue, protect, and prepare—you have a holistic framework, whereby the CT bits in relation to ‘pursue’—which also involves the military dimension, security services, etcetera—is only one set of a whole framework where you have either ‘prevention’ or ‘pursue’ or ‘prosecute.’ Then you have the other two Ps—‘protect’ and ‘prepare’—which are helpful when you have a terrorist incident and how quickly you can come back from it. Here, I take my cue from Sir David Omand, who really was the principal architect of this [the United Kingdom’s four ‘P’ approach]. He said that all counterterrorism needs this strategic framework because it is essential to bounce back to normalcy as quickly as possible once terrorism occurs. So, strategic communication becomes very important to how you control the narrative once something happens—crisis communication, strategic communication, etcetera after an event.

There are also communicative elements in how different security services in Europe have different levels of openness in relation to the public. If I just take my own, the Swedish security service, they were very closed before because they were more directly involved in counterintelligence against the Russians, but gradually when CT came around with 9/11, the value of strategic communication was understood—communication about the threat, communication about the intersection of threats and deterrence, a kind of signaling to the adversary that they are in focus.

We also have hybrid threats. A good example is the fact that the Iranians and particularly the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) have sent agents to Sweden to assassinate leaders of the Jewish community, and they’re also using criminal groups as a sort of cheap, proxy wars; they don’t need to use Hezbollah in the same way, which also creates plausible deniability. Now, the security services are out communicating this threat—calling the Iranians out, calling the network out—and that is an important part of creating deterrence, accountability, and that there is a cost. It also creates political pressure because now there are calls for classifying the IRGC as a terrorist entity within the European Union. Sweden is calling for that actively.

CT’s Relevance, or Irrelevance, to Strategic Competition in the European Context

This can be seen in different areas. First of all, we have the listings of terrorist groups, and there, you have different states taking different approaches. We have the U.K., the Netherlands, Germany, and, of course, other Five Eyes countries, they all have designated Hezbollah, the entire entity, which only makes sense as it is under one command. So, you have had a gradual slide towards an understanding that you cannot isolate these different things [non-state and state level threats]. For example, you cannot speak about Hezbollah without speaking about Iran due to their intertwined operational cooperation.

Of course, these hybrid threats with Iranians behind actions in Europe has meant that the Iranians are more offensive, but also that European counterterrorism efforts are correspondingly responding to this threat more assertively. The fact that you have criminal groups acting on behalf of terror states is quite a new and important development in terms of potentially classifying the IRGC Revolutionary Guards Corps as a terrorist entity, or individuals within that organization. This is not new to the U.S. It’s not new to Canada and others.

The 7th of October [attack] also comes to mind. I think the financial architecture, but also the U.S. listings, the Treasury listings, etcetera, also have a massive impact on Europe, forcing Europe also to adhere to the sanctions lists. These lists, particularly U.S. Treasury lists, lists of the State Department, have a massive impact on shrinking the space for different groups in the financial arena and actually changing behavior. A good example is the Nordic Resistance Movement, and the U.S. listing, and the linking of that movement to a state actor [Russia].22 Nordic Resistance Movement leaders cannot have bank accounts or travel without the fear of being subject to U.S. rendition.

In many ways, the United States is the CT conductor, which is welcome, and they are particularly effective in the financial space, that’s where it really bites. Because without the financing, terrorist groups have difficulty operating, and the U.S. sanctions regime has huge consequences for banks and other financial institutions because if you do not adhere, banks may be sanctioned themselves. This is a huge instrument.

What we need in Europe is working [in a] more focused [way] on tackling the financial architecture of terrorist groups and networks, and particularly when terrorist groups use humanitarian causes, using fronts as covers, as a method of collecting massive amounts of money.

We’ve been very slow tackling the financing of all these different groups. A good example right now, there’s the case of [Amin] Abu Rashid in the Netherlands,23 who has been accused of financing Hamas within Europe. He [was allegedly] using the European Palestine Conference as a means to generate funding, etcetera. So, I think that there’s a sort of change in mood after the 7th of October, especially in relation to what is happening with Hezbollah and Hamas and their support infrastructure in Europe, which is starting to be tackled more. However, E.U. states need to move faster and more offensively against this.

Counterterrorism and Deterrence in the European Context

To be honest, the first thing I think of is the Israelis—of course, what they are doing now to reestablish deterrence, to reestablish dominance. Their incredible intelligence operations against Hamas and Hezbollah signal that they can reach anyone, anywhere, anytime.

[There is often] a five-grade scale. In Sweden and Denmark, the threat level is [currently] at a 4 (out of 5). So, [through these systems] you’re trying to communicate to the public, but you’re also communicating to states that they may also be consequences for states using states’ sponsorship.

Highlighting the actors, this also becomes part of deterrence. The U.S. has been doing this, of course, a long time, but I think the Europeans are waking up more to this hybrid threat of warfare, which involves Russia and the Iranians particularly.

There is also the basic issue of having the adversary spend more time thinking about their own security than plotting and planning. There are European services that have a more offensive reputation. Denmark, for example, has been extremely offensive, and over a period of time, it became very clear that extremist groups or terrorist groups, etcetera didn’t want to base themselves in Denmark because they were intercepting and disrupting their activity either earlier or in a much more forceful way.

So, you have counterterrorism as signaling—that if you are based in a particular territory, you will face pressure. [The] U.K. is another example. The U.K. has a reputation for being a bit lenient on certain groups, has been traditionally. This is, of course, historically why the French were complaining about Londonistan etcetera, that they allow groups to function. As a result, you have different spaces across Europe.

Belgium is another example where you have, until the [2015] Paris and [2016] Brussels attacks, a sort of recognition that the Belgian CT community needed to step up. So, you have differences all across Europe in relation to how you deal with this threat. The Italians, as soon as they detect any threat—extremists, etcetera—they expel them to North Africa and normally this wouldn’t happen in other [European] countries. It wouldn’t happen the farther north you get. The more sort of risk averse [a country is], the more conservative the response may be in relation to some actions that may be taken against particular organizations and groups.

Different states also have different terrorism legislation. In some states, it can work as a form of deterrence: You can lose your citizenship if you get convicted. I testified in the Mullah Krekar case24 in Norway [and] also in the Said Mansour25 case in Denmark. Said Mansour was involved in the 2003 suicide bombing in Casablanca, Morocco, and was also the main Moroccan jihadist leader figure in Denmark who became a towering preacher like Abu Qatada or other such leaders. Mansour was prosecuted. And he had dual citizenship (Moroccan and Danish), and the Danish government brought charges for a relatively minor offense which [led to the withdrawal of] his citizenship and [his expulsion] back to Morocco. So, if you’re dual national, withdrawing your citizenship or not granting citizenship to [individuals who pose] security threats [who have] sought asylum is actually a form [of] deterrence, because [the message is] then ‘you will lose all your benefits. You won’t be able to stay in the country.’

When it comes to deterrence, another weakness in counterterrorism in Europe is the listing system that we have. It’s a bit antiquated. It needs to be updated, and it needs to be more developed along the lines of the United States, whose system involves individuals and entities, in addition to groups. The European framework could also be developed and updated much more often.

Conclusion

The CT ROI framework examines value through a convergent lens where counterterrorism and strategic competition can be mutually supporting and complementary activities. That is its starting point, and it may be the area where the framework proves most useful. That is because since 9/11, U.S. counterterrorism efforts have evolved into being more than activities focused on threat mitigation. For the United States, that is the core element of CT and it always will be, but over the past two and half decades, counterterrorism has also been a form of influence, a tool—and in some cases a strategic one—that the United States has leveraged to cultivate and enhance partnerships, to build trust, to offset direct time spent on CT, and to make progress toward other goals. This is why the CT ROI framework places emphasis on direct and intersectional CT returns.

The interviews featured in this article provide additional context and important color to how CT and strategic competition intersect generally and in specific regions—Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. The interviews highlight opportunities. They also offer cautions and provide insight into risks and other issues that need to be considered as the United States and its partners continue their quests to find what ‘CT right’ looks like in different regional areas.

As noted by Christopher Faulkner, it is also helpful to view “CT in the African context through the theme of resilience” as reflected in different ways.26 He also stressed that CT only gets one so far: “It must be a more comprehensive project, focused not exclusively on military means but instead on prioritizing non-military instruments of national power that can genuinely differentiate the United States from its strategic competitions.”27 Leveraging CT as a form of influence in Africa can also be a “double-edged sword … [it is] arguably necessary as a means of yielding influence … [but] the risk is that such provisions, in isolation, rarely if ever resolve the insecurity and then can unintentionally help contribute to anti-Western sentiment.”28 Or to put it more simply, CT can provide short-term threat mitigation ‘wins,’ but if those gains are not lasting, it can help to create an environment that is less friendly to U.S. interests and lead to longer term ‘loses.’

Michael Knights stressed that “counterterrorism support gave us a seat at the table we otherwise wouldn’t have had in Iraq, in Yemen.”29 He also made the important point that “we deny space by continuing to operate in space,” even if that is hard for Americans, who have a “decisive strategic culture that likes to win,” to accept.30 Drawing on the case of the Iraqi CTS, he offered cautions about partner success stories and the sustainment of capabilities: “It’s going wrong as we speak. It has been allowed to atrophy and to be politicized, and the best example of what we will try and do with CT is starting to fall apart, sadly, in Iraq. It’s a good case study of what you must not let happen.”31

Magnus Ranstorp called attention to the intersection between terrorism and hybrid threats in Europe, how counterterrorism approaches are evolving on the continent, and areas that deserve attention and could be improved. “A good example” of hybrid threats “is the fact that the Iranians and particularly the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) have sent agents to Sweden to assassinate leaders of the Jewish community, and they’re also using criminal groups as a sort of cheap, proxy wars.”32 Ranstorp viewed sanctions, and particularly financial sanctions, as being an area where Europe needs to work in a more focused way because “we’ve been very slow tackling the financing of all these different groups.”33

Through all of this, there is also an underlying current of the importance of information and messaging. While several of the returns on CT investment have tangible outputs and can be cleanly measured, there are also many returns on investment that are psychological and can be difficult to quantify. These types of returns, more than others, require a deliberate dominance of the information space. The CT enterprise must rapidly combat misinformation and disinformation by adversaries and must ensure that allies and partners know when U.S. CT activity has resulted in a measurable disruption and defeat of an ongoing or planned attack. Information operations and strategic messaging help take the measurable outcomes and help translate them into the psychological effects. This is demonstrated by greater trust and confidence in U.S. CT forces, which translates to greater access and influence for U.S. diplomats and an increased likelihood of cooperation in the strategic competition environment.

The authors provided this framework as a starting point to developing a more adaptable and integrated model for investing in a resource (CT) that can provide direct and various types of intersectional returns. When used properly, the framework may have the ability to increase shared understanding regarding the broad utility of CT forces, their interoperability, their role in campaigning, and their ability to shape or build momentum for other pursuits in support of combatant commanders and the president.