Despite calls for Europe to play a bigger role in transatlantic security, Brussels has been reluctant to embrace NATO ally Turkey as a closer partner in its defense.

Two major disruptions are now reshaping the European security paradigm. First, Russia’s full-blown invasion of Ukraine shattered the prevailing wisdom of the 1990s that confrontation in Europe was a thing of the past and that peace was the new normal. Quite the opposite: war is back on the continent.

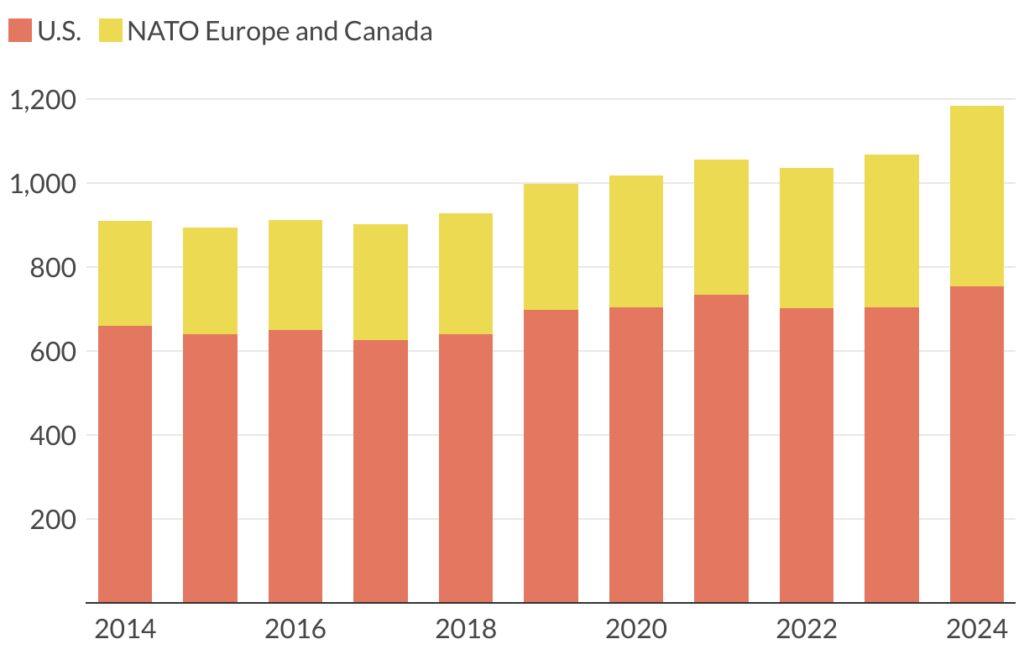

Second, there are steady signs from across the Atlantic that the United States’ commitment to European security can no longer be taken for granted. Washington’s energy and resources could well be overstretched by other global demands. Or, even worse, as implied by former (and possibly future) President Donald Trump, absent a substantial commitment from European nations to bolster their security, America may choose to look the other way when Europe is confronted by aggression.

The combined shock of these disruptions has revitalized the debate over strengthening the European defense pillar of transatlantic security and the NATO alliance into one that can stand more firmly alongside the U.S., which together with Canada comprises the North American pillar. Turkey, as a NATO ally and a formal EU candidate (albeit a remote one) with interests in the continent’s security architecture, is central to this debate.

The discourse around Western security policy has increasingly seen calls to “Europeanize NATO to save it” and for “a more European NATO,” to cite some typical attention-grabbing framings. Washington’s thinking has also been evolving in support of the idea, as exemplified by President Joe Biden invoking “the importance of a stronger and more capable European defense” in an exchange with his French counterpart. Over the years, this has become an often-repeated assertion in NATO documents, as was the case in the Washington Summit Declaration from July 10.

Geopolitical circumstances provide a strong impetus for such a goal. However, translating it into reality is another story, given the complexities and practical difficulties of conceptualizing a more robust European defense pillar for NATO.

Facts & figures

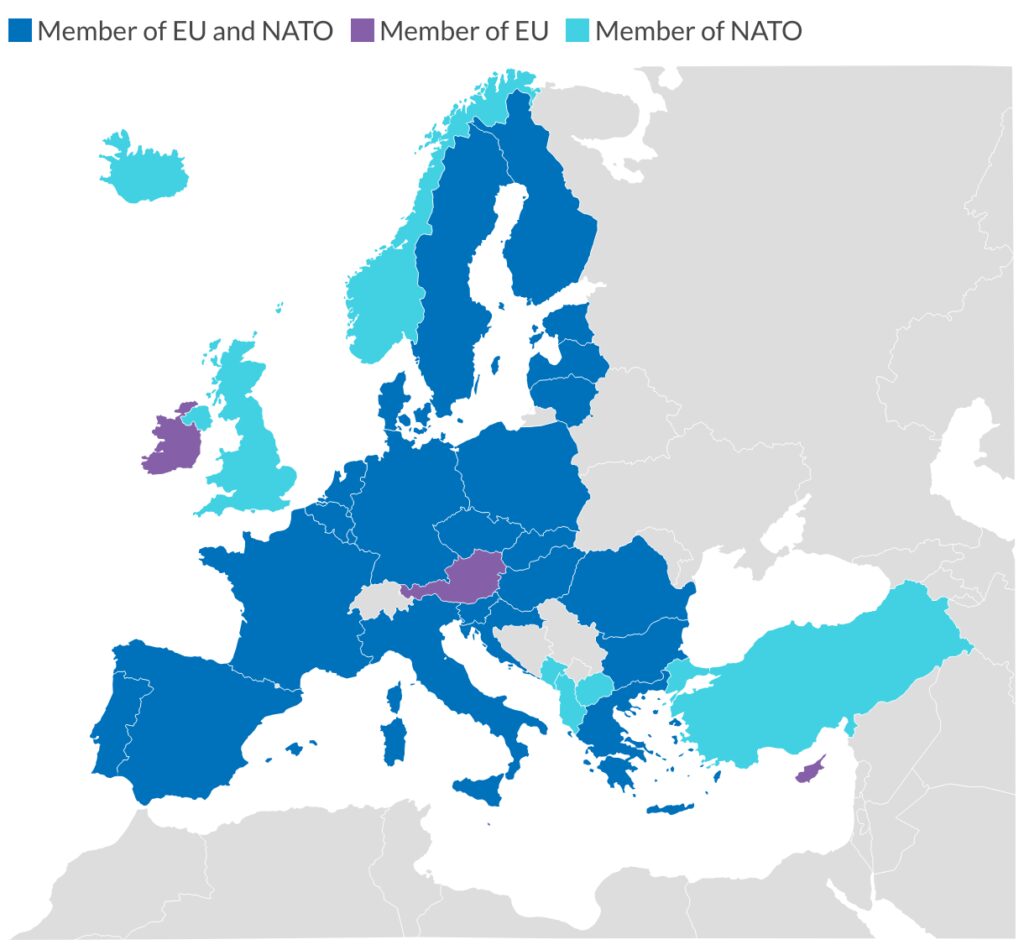

NATO and the EU in Europe

Tensions between NATO and the EU

For one, there is traditional skepticism among European Atlanticists to any perceived distancing from Washington. The notion of greater prominence for the European pillar could, at least in theory, imply some decoupling from the U.S., raising the eyebrows of devout Atlanticists.

Another hurdle is the institutional rivalry, hidden yet very real, between NATO and the European Union. Despite best efforts, NATO’s central role in the collective defense of transatlantic allies, and the EU’s growing aspirations to develop its own defense capabilities and achieve strategic autonomy, tend to come into some conflict. This was on display earlier this year when NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg warned Europe against going it alone on security, starkly declaring that “the European Union cannot defend Europe.”

An integral part of this institutional challenge comes from the mismatch in the membership of NATO and the EU. This leads to political difficulties – including, significantly, those related to Turkey.

Turkey at arm’s length

In his now-famous “Europe Speech,” French President Emmanuel Macron broke some new ground on the institutional challenge. He tweaked France’s classic, EU-centric approach by arguing for thinking beyond “institutional” limitations in European security. In a follow-up interview, Mr. Macron elaborated that Europe’s security was an existential debate to be had in a continental, not institutional, framing, and that non-EU countries like the United Kingdom and Norway needed to be included. Even if it was still arguably EU-centric, the French president seemed to offer a more inclusive vision for security policy. But still, this embrace did not include Turkey.

This has become a pattern in the EU. For several years Brussels has made a clear distinction between Turkey – the country that has been kept at candidate status for the longest time – and other aspirant countries. The EU has bunched together Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Kosovo, Montenegro and Serbia under a “Western Balkans” rubric that includes an ambitious growth plan to facilitate their integration with the EU (and that excludes Turkey). A similar contrast exists between the EU’s enthusiasm toward new candidate countries like Ukraine, Moldova and (to some degree) Georgia, versus its muted approach to Turkey.

To be fair, Turkey shares some blame for this situation. It failed to live up to key commitments as a candidate country. Ankara has often simply paid lip service to its EU ambitions amid its democratic backsliding, without any credible agenda for reform. In 2018, the EU Council asserted that Turkey had been moving away from the Union and declared that accession negotiations had effectively come to a standstill. This was followed in 2019 by a European Parliament vote calling for the suspension of negotiations. Meanwhile, the Turkish leadership’s implacable, tactical hedging – such as seeking membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization or the BRICS grouping – has deepened doubts in Brussels over the country’s trajectory.

Facts & figures

Defense spending, NATO members

Nevertheless, in practical terms, Turkey is a natural partner in any bolstering of the European defense pillar, given its longstanding role in the Western security architecture, a booming defense industry and formidable, combat-proven capabilities. A wide array of security challenges, including Russian aggression as well as risks and uncertainties emanating from Europe’s south, increase Turkey’s importance for the well-being of the continent.

Yet the historically complicated politics around the country’s European vocation presents a challenge. Ankara’s place in Europe, and by extension its participation in European-branded projects, is not a universal given. Depicting Turkey outside of the European fence comes naturally to identity-driven politicians and is often a point of agreement among the continent’s rising right-wing parties. This dynamic will not go away quickly, if ever. Tensions between Turkey and Brussels (and certain European nations) compound the challenge.

Even in the wake of the war in Ukraine, the EU has chosen to refrain from engaging Turkey in any meaningful manner in terms of defense and security. Conflicting factors include the Cyprus dispute, Turkish-Greek differences in the Aegean Sea and the national positions of Union members like France, Austria and others. The EU disregards geostrategic imperatives at these members’ behest and is keeping Turkey at arm’s length.

Missed opportunities

Consequently, Ankara is excluded from the EU’s permanent structured cooperation activities, including the military mobility project, a supposedly vital area of cooperation with NATO aimed at seamless military connectivity across the continent. Politically motivated objections also prevented the EU from tapping into Turkey as a supplier of much-needed artillery shells and drones for Ukraine. These are areas where it seems plainly sensible for Turkey and the EU to have organic relations, but politics prevails, regardless of the lost opportunity.

The daylight between Ankara and the EU and various European actors effectively precludes mutual empowerment at a shared cost. This dynamic may persist on a grander scale if Brussels’ practice of drawing the “European border” at the Turkish frontier also applies to its vision of the European defense pillar.

Outgoing EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell seemed to acknowledge this risk in a report he prepared at the end of 2023 on the state of play in EU-Turkey relations. He made the realistic assessment that, especially in the current security environment, Turkey and the EU have much to contribute to one another’s security and that it made sense to work together. Whether this sober proposition will be translated into policy is questionable.

Scenarios

Unlikely: Calls for a more proactive European defense subside

In one scenario, the debate on strengthening the European defense pillar of the transatlantic alliance dies out, and Turkey’s position in European security policy remains more or less unchanged. While waves of this same debate have previously come and gone, the circumstances today are different, and there is likely no putting the genie back in the bottle.

Europe is in a new security paradigm, while American priorities are changing. The combined effect will keep the conversation on the need to bolster Europe’s role in the Western security alliance alive and pertinent.

Unlikely: Seamless consolidation including Turkey

Calls for a more robust European defense pillar are often strong in principle but weak in detail. Who would participate, and how, is unclear. One can even come across two different understandings of the vision in the same city. At NATO’s headquarters in northeastern Brussels, most (aside from some usual suspects) would consider Turkey as integral. But on EU premises in downtown Brussels, there would be little appetite to include Ankara when conceptualizing the defense of Europe.

Advocacy for a strengthened European defense pillar has traditionally been led by Euro-centric actors – but today, the idea is seeing increasing U.S. acquiescence. Resolving Turkey’s role will remain a challenge, especially as the political arm wrestling with EU members continues. Any breakthrough that would incorporate Turkey into EU-led thinking is currently unlikely. And, with no apparent prospect for a political solution to the Cyprus dispute, Ankara can be expected to return the “favor” by maintaining its blockage against Cyprus’s involvement in NATO-led activities.

All these political realities mean that the functioning, seamless consolidation of a European pillar of transatlantic security that includes Turkey is not within reach.

Likely: The EU presses on without Turkey, fragmenting European defense

The EU’s internal resolve to strengthen its defense capabilities and diminish its reliance on the U.S. is stronger than ever, and will likely carry the momentum.

But this does not come without challenges, even assuming that Washington backs the idea. Beyond a commitment to the principle, there no is clear consensus among the relevant states on how to proceed with the details. Fundamental conflicts remain due to the institutional rivalry and membership conundrum between NATO and the EU. Additionally, actors will seek to avoid a wholesale American disengagement from the continent while managing the skepticism of Atlanticist EU dissenters and handling the complicated situation of Turkey’s major role in NATO.

There is no easy solution to any of these challenges. The EU will likely continue to exclude Turkey from its security considerations, and Turkey will in turn seek to protect its interests by leveraging its geostrategic importance and its weight as a leading NATO ally. Whatever engagement Ankara is unable to attain from EU institutions, it will try to make up for through bilateral engagement with the EU member countries more amenable to cooperating with Turkey, such as Spain and Italy. And it will seek to build synergies along the way with other non-EU European allies, like the United Kingdom and Norway. This fragmented outcome is the more likely scenario under the current circumstances.