As Bosnia and Herzegovina prepares to take on greater responsibility for migration management, one of the main challenges remains that of guaranteeing people on the move adequate and dignified reception conditions

As Bosnia and Herzegovina prepares to take on greater responsibility in managing migration, one of the main challenges remains ensuring adequate and dignified reception of migrants.

After years in which the management of migration flows in Bosnia and Herzegovina was entrusted mainly to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the Bosnian and Herzegovinian authorities are preparing to take a more active role in migration policies to align with European standards and fulfill BiH’s commitments as a candidate country for EU membership.

Despite the reassurances of the IOM and the EU, according to which the migration situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina is stable, in recent years some critical issues have emerged regarding the reception of migrants in the country. Critical issues that have led to the creation of informal camps, causing tensions and controversy over the work of the IOM in the country.

While informal camps offer migrants greater freedom than formal reception centres, they have often been criticised for inadequate sanitation and hygiene conditions, and have become the scene of clashes and human rights violations.

Despite these critical issues, more than half of migrants crossing Bosnia and Herzegovina seek shelter in existing facilities, still defined as “temporary reception”. This is confirmed by a recent report produced by the IOM based on interviews with 822 migrants, conducted in June this year in the Western Balkan countries. The research showed that 75% of migrants interviewed in Bosnia and Herzegovina transit through reception centers, although they remain there for an average of about 35 days and then continue their journey. The same report also shows that for 46% of migrants arriving in the Balkan countries, finding accommodation or a place of shelter is one of the most pressing needs during the journey along the Balkan route.

In an article published in the Princeton Journal of Public and International Affairs, researcher Rio Otsuka argues that Bosnia and Herzegovina should recognize the “obstacles with providing living conditions in reception centres that meet international standards” and “implement policies to address them through continued coordination with international organisations and NGOs”.

If Bosnia and Herzegovina is to take on more responsibility for migration management, it must adopt an approach that includes a reform of the migrant reception system.

Migrant reception, a lingering issue

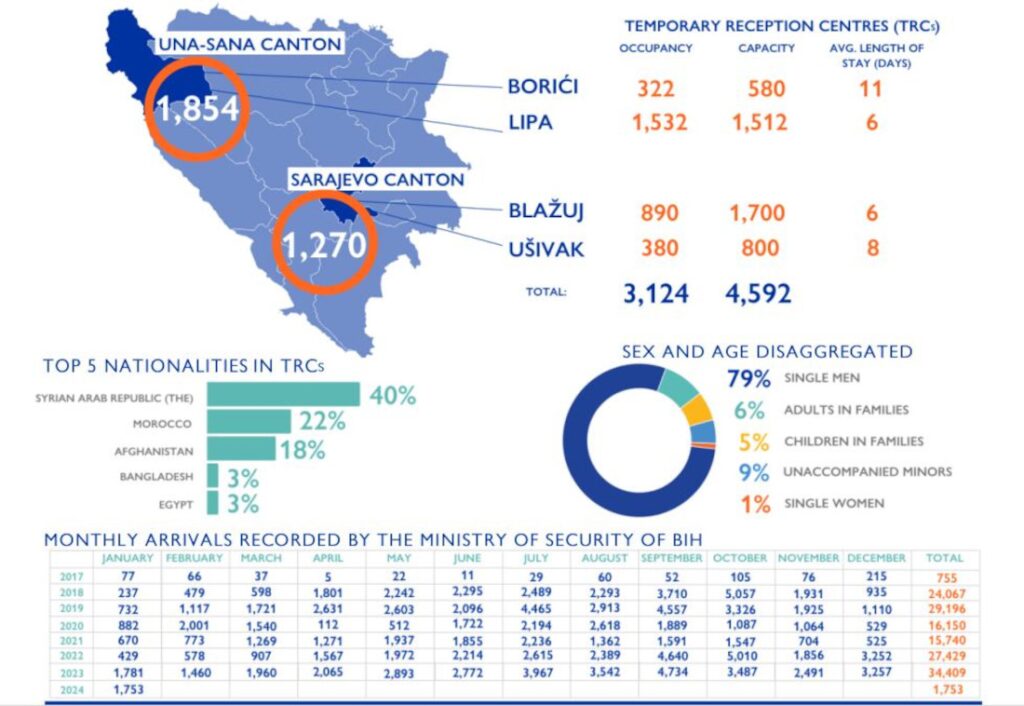

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, as in most Western Balkan countries, an initial increase in migrant arrivals was recorded in 2015 with the large exodus from Turkey to Northern European countries, which then grew from 2016 until reaching a peak in 2019 with 29,124 arrivals. After a constant decline until 2022, in 2023 the number rose again, reaching 34,409 arrivals between transiting people and refugees who remained in the centers, as shown in the IOM report of January 2024 .

However, as migrant arrivals started to rise, the authorities of Bosnia and Herzegovina failed in properly managing the situation, so in 2018 the reception of migrants was entrusted to the IOM. Over time – as RiVolti ai Balcani writes – “the mechanism has become increasingly complex, cumbersome, and unmanageable”. While 70,000 migrants passed through Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2020 alone, the number of available spots for accommodation in the “temporary reception centres” and “provisional camps” never exceeded 8,000.

As Al Jazeera reported at the time, of the thousands of migrants in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2020, a quarter slept in abandoned buildings or out in the open in forests and on roadsides, concentrated in the Una Sana Canton near the border with Croatia. The tendency for migrants to concentrate near the Bosnian-Croatian border, in the hope of entering the EU, had led to the creation of makeshift camps in places such as Bihać and Velika Kladuša.

Associated Press found in 2021 that the camp near Velika Kladuša was simply made of sticks covered with nylon, and that there was “no running water, lavatories, showers or electricity”.

In Bihać, similar stories were collected in 2019 in the Vučjak camp near Bihać, set up on a former landfill, where poor sanitary conditions led to the spread of diseases such as scabies, lice and hepatitis. Despite the constantly deteriorating situation, the citizens of Bosnia and Herzegovina did everything they could to support the migrants. In Velika Kladuša, locals and international volunteers offered shelters, hairdressers gave free haircuts, and some local restaurants offered free meals to migrants.

Both the Vučjak and Velika Kladuša camps were eventually cleared. In 2020, the EU funded the construction of an emergency camp – Lipa, 30 km from Bihać – run by IOM, with the aim of intercepting migrants living on the streets and transferring them here even against their will. The Lipa camp came to host over a thousand people and was – as stated in a report published by the Transnational Institute – “without adequate sanitation, cold, dangerous, with poor food”. And, following a fire in December 2021, it was rebuilt and partly transformed into a detention centre.

Currently, there are four migrant reception centres in Bosnia and Herzegovina – Borići, Lipa, Blažuj and Ušivak. The process of transferring responsibility for their management to local authorities has taken place in the Lipa and Blažuj camps, while the other two camps are still in the process of being transferred from IOM to the Office for foreigners .

If it is true, as Rio Otsuka argues in hers analysis, that the Bosnian-Herzegovinian authorities have the capacity to manage the migratory situation adequately, it is also true that the great challenge remains that of providing migrants, asylum and international protection seekers with a better reception in line with international standards as prescribed by the laws in force in the country: the law on asylum, which is in need of reform because it dates back to 2006, and the “Law on Foreigners” whose updates came into force in September 2023.