Recommendations

• Put an emphasis on reintegration instead of criminalization;

• Tailor responses to the returnees based on their motivations to join IS, motivations

to return and gender/age dynamics;

• Engage local religious, family and school communities in the process of

reintegration;

• Address push factors such as poverty, inequality, and economic insecurity.

Executive summary

The Islamic State (IS) will remain a threat in 2018, experts say. Thousands of

foreign fighters are now coming back to their home countries following the collapse of

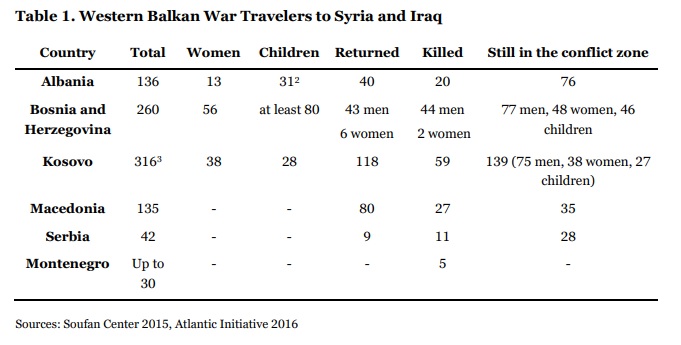

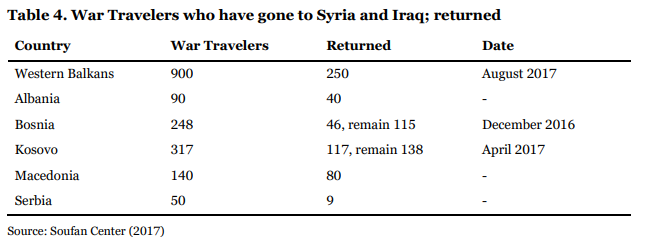

the so-called “caliphate”. From the around 900 people from the Western Balkans who

have travelled to Syria and Iraq between 2011 and 2016, 250 have already returned.

Despite the different reasons for doing so, returnees raise security concerns, to which

local governments should respond.

The key challenge for security actors is how to assess the threat posed by former

IS combatants and their families. Although returnees have not contributed to the threat

of terrorism locally, they create some degree of risk, not only to the Western Balkans but also to Europe as many returnees have dual citizenship or links to their diaspora

communities across the continent.

There are at least three criteria to consider in developing policies. First, returnees

vary in their motivations to travel to the battlefield. Second, they are coming back home

for different reasons. Third, gender/age characteristics matter. Thus, a tailored

approach to each returnee is necessary.

This policy paper addresses the issue of returning foreign fighters to the Western

Balkans by analysing the threat and the response. It discusses key actions that local

authorities should consider. Recommendations here derive from existing strategies and

approaches in other states. “Hard” measures such as prosecution and detention have

been already applied by the countries in the region. However, individual risk

assessment, as well as “soft” policies like rehabilitation and reintegration, are becoming

essential to address the problem in the long term.

Central European governments should consider a more active role in the region

by supporting local governments in dealing with the issue of returning foreign fighters.

The Visegrad Four states should support the dialogue between Western Balkan countries

(especially between Serbia and Kosovo), and to encourage more active security

information sharing among the Western Balkans states, and with the EU. Central

European countries have also the capacity to assist in reintegration policies and

addressing push factors for radicalization in the region.

The context

More than 42 000 people from 120 countries have travelled to Iraq and Syria to

join the so-called Islamic State (IS) (RAN 2017). Of the 5000-6000 European nationals,

most are citizens of Belgium, France, Germany and the UK (Soufan Center 2015). The

flow of fighters has significantly decreased as a result of the strict measures that countries

have applied to prevent citizens joining IS. As IS has begun to lose its territory, the number

of war travellers declined from around 2000 a month in 2014 to around 50 a month in

September 2016 (Reed and Pohl 2017b, 2017c). At the end of 2016, around 15 000 were

still in the conflict zone (Interpol 2016). However, many have returned. At least 5600

citizens from 33 countries who travelled to Syria and Iraq between 2011 and 2016 have

already come back home (Soufan Center 2017). About one third of European IS

combatants have returned to their home countries While many of them are currently under prosecution or already in jail, some have certainly disappeared from the view of the

security services (RAN 2017).

The Journey of the Foreign Fighter Concept: From Civil Wars to

Terrorism

The most recent wave of foreign fighters to Syria and Iraq is not a new

phenomenon. From the Spanish Civil War to the conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen,

Somalia, Bosnia, and Chechnya, foreign insurgents have always been part of the war

theatre. Nevertheless, foreign fighter participation has only become a serious political

issue worldwide with the rise of the Islamic State (also known as IS, ISIS, ISIL, or Daesh).

Research on foreign fighter participation does not have a specific place in the

literature, it is rather scattered among different fields – civil wars, transnational social

movements or terrorism. More recent and comprehensive accounts on foreign fighters

appeared following the civil war in Syria and the rise of IS (Hegghammer 2015, Roy 2017,

Coolsaet 2016, Neumann 2016, Nesser 2015). The declaration of a caliphate enabled IS

to call on Muslims on a global basis by employing the narrative of statehood. Like in

previous wars, a humanitarian crisis attracted volunteers from abroad and thus, shifted

the struggle from a national civil war to a supranational jihadist conflict (Donnelly,

Sanderson and Fellman 2017).

As research on foreign fighters is predominantly empirical, it lacks conceptual

clarity. Foreign fighters might be insurgents but not necessary terrorists (Mendelsohn

2011); they might be mercenaries or volunteers (Bakke 2010); they might have their own

motivation to join a foreign war or be forced by other individuals, or certain circumstances

(Coolsaet 2011). Despite all these dimensions, there are similarities on the empirical level,

which help draw the boundaries of the phenomenon. We call them foreign fighters

because they join a cause with geographical, national, and ideological determinants that

they embrace like their own although they do not initially belong to it. Various types of

ethno-nationalism or religious ideologies have triggered foreign fighter participation in

recent wars. All contemporary examples follow similar patterns: local conflicts turn to

supranational struggles and draw worldwide volunteers (Donnelly, Sanderson, and

Fellman 2017). This is the case of Syria but also Iraq, Chechnya, Bosnia or Afghanistan.

The lack of a coherent definition of a foreign fighter allows various applications to

appear in the work of academics, security experts, policymakers, and journalists

depending on the conflict that they study. The UN definition of those who travelled to Syria and Iraq to join IS has been ‘Foreign Terrorist Fighters’ (UN Resolution 2178).

Although researchers, security experts, and policy makers have quickly adopted this

definition, the label “terrorist” is not helpful from a public policy perspective to distinguish

among various categories within the pool of returnees. This policy paper employs the term

‘war travellers’ to describe more broadly those individuals from the Western Balkans who

have travelled to the conflict area between 2011 and 2016. It comprises the variety of

possible reasons for these individuals to go to the battlefield as well as to come back home.

Western Balkans and the Foreign Fighter Phenomenon – from

Demand to Supply

To understand what the Western Balkans countries are currently dealing with, we

need to look at the foreign fighter phenomenon historically. The recent wave of war

travellers to Syria and Iraq is not unique to the region. While the Balkan states are among

the active suppliers of IS warriors, previously they were on the demand side of the

phenomenon following the collapse of Yugoslavia. Bosnia became a magnet for foreign

fighters after declaring independence in 1992 and trying to separate. Bosnian Serbs

refused to accept this step and undertook military actions against Bosnian Muslims

backed by the Serbian army (Donnelly, Sanderson, and Fellman 2017). The ethnoreligious

dimensions of the conflict as well as the terrifying massacres committed against

civilians evoked transnational defensive mobilization and attracted former mujahedeen

from the Middle East. For instance, Sheikh Abu Abdel Aziz, a commander and associate

of Osama bin Laden, established the El Mudzahid Battalion (“Battalion of the Holy

Warriors”) in 1992 (ibid). The conflict in Bosnia attracted Afghan war veterans, as well as

new recruits seeing Bosnia as “a Muslim country, which must be defended by Muslims”

(New York Times 1995). Following the end of the war, most foreign fighters left Bosnia

and later some of them returned to Kosovo when the situation there escalated in the late

1990s (Corovic 2017). Both conflicts enjoyed opportunistic support by Muslim extremists

around the world who used the chance to promote radical ideologies in the region (ibid).

With the rise of IS, the region has become a supplier of war travellers. Following

the civil war in Syria, volunteers from the region felt obliged to join the conflict to help

their fellow Muslims in need (ibid). Most of those Balkan fighters, who initially (before

2014) joined various rebel groups in Syria, moved to IS after its emergence, along with Al

Nusra (Time 2016). The number of foreign fighters from the region reached its highest

level in 2014 when Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi declared the formation of a caliphate and called on

Muslims from around the world to join it. The mobilization peak was in the second part

of 2014, continued in 2015 and has since decreased.

Between 900 and 1000 fighters from Western Balkan countries have travelled to

Syria and Iraq between 2011 and 2016. The most active ‘exporters’ of war travellers have

been Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Albania, and Macedonia. Citizens of Serbia and

Montenegro have also contributed to the foreign fighter mobilization.

The demographic dynamics confirm that many men from the region left to the

conflict zone followed by their families. This trend is particularly visible in Bosnia and

Herzegovina where a significant number of male war travellers went to the battlefield with

their wives and children (Azinovic 2016). Many of those who joined IS had criminal

records prior their departure, others were veterans from the Yugoslav wars, but the

majority did not have any previous combat experience (ibid).

From the Western Balkans to the „Caliphate” and Back

Balkan war travellers have gone to Syria through one of the major transit routes –

Turkey. Due to the geographical position of the Balkans and the liberal visa regime with Turkey, it is not easy to say with certainty how many Balkan fighters have made their way

to the battlefield (Corovic 2017). At the Turkish-Syrian border, they get help by IS

affiliates who facilitate their journey (Soufan Center 2017).

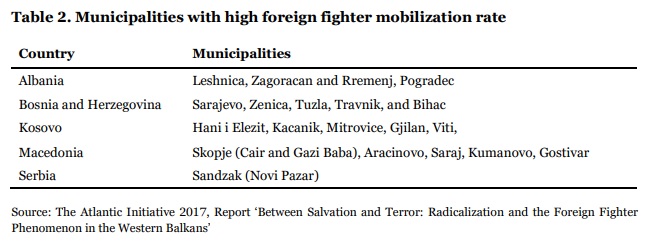

Despite the conflict heritage of the region, IS mobilization has not affected entire

societies in the Western Balkans, but it has been concentrated in certain towns and

villages. The table below gives information about the geographical dimensions of the

phenomenon.

The war travellers’ mobilization, therefore, does not follow a random distribution.

These hotspots are geographically close to each other. Some of the radical networks appear

in bordering regions, others in the capital cities and major towns. Yet, local networks in

different countries connect through identity links. Various empirical sources show that

both Bosnian (including fighters from Bosnia and Sandzak, Serbia) and Albanian

(including fighters from Albania, Kosovo, and Macedonia) contingents have cells across

the region linked though charismatic leaders, ideologues (radical imams), and social

circles (Azinovic and Neumann 2017, Azinovic 2016, Kursani 2015).

The Threat and the Perception of the Threat

The conflation of the threat itself and the threat perception has implications for the

creation of counterterrorism policies. The real terrorist threat relates to a small probability

of an individual in a certain society to become a victim whereas the perception of the

terrorist threat concerns larger parts of a certain population (Wolfendale 2006).

Terrorism induces fears within a society due to its decentralization and unpredictability.

Thus, politicians should react not only to a threat but also to the societal perception of

terrorism that is much broader in its nature. In addition, the fear of terrorism can influence not only security policies but also electoral outcomes (Berrebi and Klor 2008).

Consequently, it might be a source of political manipulation as well as power.

The perception of the threat: A 2017 survey by Pew Research Center shows that

people globally see both IS and climate change as the main threats to national security

(Poushter and Manevich 2017). Moreover, IS is clearly the primary concern for most

states in the EU. There is no comprehensive data concerning the attitudes in the Western

Balkan states, nevertheless, public fears of terrorism have been part of the political agenda

in the region over the past years.

The threat: There are at least four interconnected threats that relate to foreign

fighters (or war travellers): the travel of foreign fighters, their return to their counties of

residence, the threat posed by lone actors and sympathizers who carry out attacks at home,

and finally, an increasing polarization of a society (Reed and Pohl 2017c) . Reed and Pohl

argue that changes in any of these aspects have an impact on the others (ibid).

Consequently, policies designed to tackle one aspect of the threat may have effects on the

other aspects.

The major concern of security experts across Europe is the growing number of

returning individuals who have lived and fought with IS. Both the ongoing conflict in Syria

and the defeat of the so-called “caliphate” have raised worries within national security

communities in Europe over massive waves of returnees. However, experts do not expect

a massive return of war travellers to Europe. Gilles de Kerchve, the counterterrorism

coordinator for the EU, says that “the intelligence community doesn’t fear a massive flow

of returnees but more a trickle” (NBC News 2017). Nonetheless, the warning is that even

a small number of returnees might have the potential to cause mass casualties. More than

40 attacks were carried out in the EU since 2014, three of them were conducted by

returning IS jihadists but accounted for more than two-thirds of the total deaths and

injuries (ibid). Three of the five attackers in Brussels 2016 were returnees and at least six

of the perpetrators of the Paris attacks were fighters returning from Syria (RAN 2017).

In the case of the Western Balkan states, there were no attacks conducted by

returning IS combatants. However, in June 2017, the Bosnian version of IS’s magazine

“Rumiyah” published an article with a title “The Balkans – Blood for Enemies, and Honey

for Friends”. The text makes explicit threats to Serbs and Croats over their roles in the

Balkan wars, as well as to Muslim “traitors”: “No, we swear by Allah, we have not forgotten

the Balkans” (Balkan Insight 2017). In addition, some returnees have dual citizenship as

well as close connections with the diaspora communities across Europe. Since “the West” remains the main target of IS (Independent 2017a) the Balkan war travellers might

represent a certain level of risk to the European security.

While the governments in Europe are worried about the rise in numbers of

returning war travellers, a recent study shows that only 1 in 360 returnees conducted an

attack after their return (Hegghammer and Nesser 2015). On the other hand, a study by

German intelligence services found that around half of German returnees remained

engaged in extremist or Salafist environments (Reed and Pohl 2017c, Bewarder and Flade

2016). Hence, while the export of terror may not be the primary goal of most returnees,

they may continue to pose a threat mainly by upholding supportive functions within

radical networks. Thus, as Reed and Pohl point out, returnees may not necessarily plan

attacks themselves, but initiate or engage in logistical, financial, or recruitment cells, or

become leaders in extremist societies (Reed and Pohl 2017b, Europol TE-SAT 2016).

National security actors, therefore, must identify who among the returnees continues to

pose a threat and develop policies to counter it.

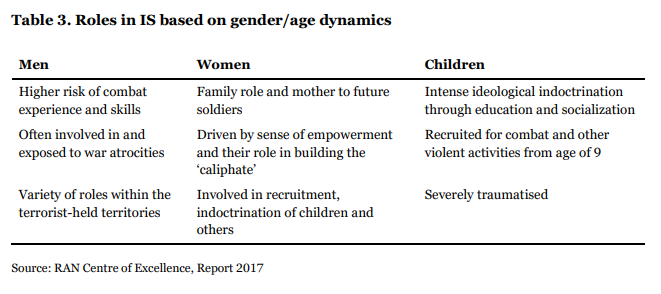

To define the threat more precisely governments in the region need to profile war

travellers and distinguish among different groups. While some are disillusioned and even

remorseful, others will keep violent extremist views and create the basis for new circles of

radicalization. Some might return with explicit intentions of planning and executing

attacks. Yet, many of those who return to their old neighbourhoods are women and

children. Looking at the IS roles based on demographic dynamics helps to profile those

who are coming back.

Several other factors, still present, shape the threat coming with returning war

travellers.

Push factors (structural preconditions): (1) Previous criminal/war experience; (2)

poor socio-economic conditions (or so-called “lack of future” factors): poverty, inequality,

lack of access to education, unemployment; and (3) local loose radical networks

supporting IS.

Pull factors: (1) IS has promised more attacks in the West; (2) at a strategic level,

IS has not admitted defeat despite the eradication of its administrative structures in Iraq

and Syria. Moreover, its propaganda has cast the loss of territorial control in Syria and

Iraq as unimportant, and just a temporary slowdown in its strategy to victory (RAN 2017).

This approach might provide a focus for some returnees to re-establish local loose

networks of former comrades or to attract new recruits (Soufan Centre 2017).

To sum up, experts expect that IS will survive the collapse of its central core. The

slowing rate of returning war travellers makes the security problem manageable.

However, the scope of the threat is blurry since it is unclear to what extent its dispersed

supporters will regroup, resurge, recruit and recreate what they have lost (ibid).

Who are the returnees? Motivations to return

There are three broad categories, which can fit under the umbrella of returnees with

respect to the threat. The first group consists of people (men, women and children) who

travelled to Iraq and Syria and have returned. The second one included those who tried

but police forces captured and returned them unwillingly. They were obviously motivated

but unsuccessful in their attempt to reach the “caliphate”. Consequently, they have

experienced a sense of failure that contributes to the likelihood that they seek other ways

to achieve their goals (Soufan Center 2017). The third category refers to those who had

the desire to go but for some reason were not able or decided to stay. These people have

identified themselves as members of the caliphate and might follow the injunction to

attack where they can rather join the battlefield in Iraq and Syria (ibid). This policy paper

focuses on the first group, as there is no reliable and publicly available data concerning

the other two.

War travellers have different reasons to return. Some are disillusioned due to

brutality, poverty and oppression that they have experienced (Balkan Insight 2017). Those

who were driven by material incentives lost their opportunities to benefit after the defeat

of the ‘caliphate’. Others still follow the ideology. Some feel that they can do more for the cause of IS in Europe than in Syria and Iraq, or even come back with a task to conduct an

attack (RAN 2017).

A recent report by the Soufan Center (2017) identifies five sub-categories within the group

of returnees as each of them brings different risks.

1. Early returnees or after a short stay: They travelled to Syria and Iraq and left

before the caliphate began to shrink. They returned because they did not find what

they were looking for and did not recognize themselves in the cause of IS.

2. Those who returned later, but disillusioned: As the report notes, all foreign

recruits to IS must have supported the idea of a caliphate to a certain extent.

Although they might have expressed disagreement with leadership, tactics, or

strategy of IS, this does not necessarily mean rejection of aims and objectives.

3. Returnees who have had their fill: They were attracted by the heroic image of

the IS fighters composed by a sense of adventure. They joined and stayed through

the high point of the caliphate in 2015 or joined once it began to lose its power.

These recruits may also decide to seek new theatres of jihad once they have rested

and recuperated.

4.Forced to return or captured: A significant number of foreign fighters have

survived the collapse of the “caliphate”: escaped, captured or surrendered. There

might be a number of individuals in each of these groups who still support the goals

and the leadership of IS. Thus, they will try to contribute to them once they return.

5. Sent home or elsewhere by IS: This category refers to the capacity of returnees

to re-establish local networks and conduct attacks.

Women and children

When IS declared the “caliphate”, its leadership called on individuals to travel to

the territory under its control together with their families, including women and children.

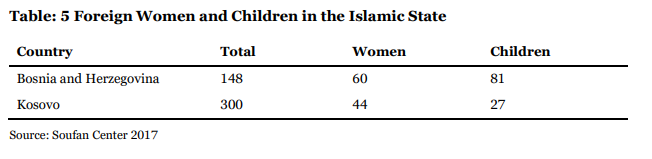

The number of women and children who travelled to Syria from the Western Balkans

remains unclear. However, at least two of the states in the region have contributed

significantly to this category – Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Kosovo.

Women: A comprehensive research by Vlado Azinovic shows that about 30% of the

Bosnian contingent consists of women. Moreover, Bosnian women represent one of the

highest proportions in the foreign communities in Iraq and Syria under the rule of IS

(Azinovic 2016). Some of them have left their homes to join their husbands or children on

the way to Syria. Another group of women has departed to the ‘caliphate’ leaving their

families in Bosnia (ibid).

While previously women had only the role to spread propaganda, marry fighters,

and take care of and indoctrinate children, they have been recently given the task by IS to

conduct attacks (Dearden 2017b). The recent IS call on women to fight frames jihad as

an “obligation” and encourages female supporters to take part in violent activities (ibid).

Furthermore, there is an increase in women’s participation in terrorist plots in Europe,

recent report shows. In the first part of 2017, sever terrorist plots in Europe (or 23% of the

total) had involved women (Heritage Foundation 2017).

Children: The number of children from the Western Balkans who travelled to Iraq

and Syria is at least 110. However, a more precise estimate is not available. Children

returning from conflict zones might be both participants in and victims of violent actions.

On one hand, IS have has considered anyone over 15 an adult, yet the age of nine

appropriate to start combat training (AIVD 2017). Children, therefore, were used to carrying weapons, guard strategic locations, arrest civilians and serve as suicide bombers

(UN Security Council Reports). Children have also been a target of indoctrination turning

them into loyal supporters for terrorist activities (RAN 2016). On the other hand,

however, the war experience has a strong impact on their moral, emotional, and cognitive

development and poses risks to their mental health in the long term (ibid).

Both groups, women and children, create a security challenge for the security

actors, as it is difficult to judge the degree of their commitment to IS as well as their

motivation to become active or passive supporters (Soufan Center 2017).

The response

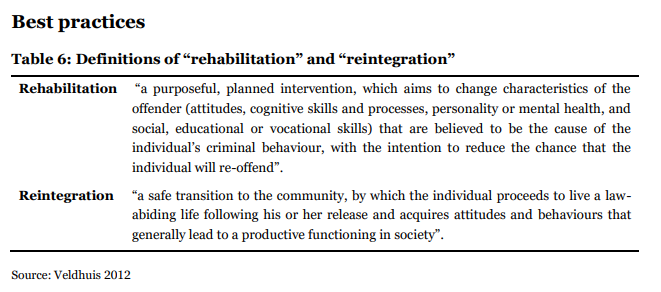

There are two streams of policies implemented by states dealing with returning war

travellers: criminalization and reintegration (Lister 2015). Security experts also focus on

rehabilitation in each stage of the criminal proceeding including the pre-trial, trial and

post-trial stage (Entenmann 2015). Some governments invest in diversion programmes

as an alternative to a prison sentence. The individual receives treatment or rehabilitation

instead of being directly prosecuted and sentenced (ibid). While some European states

have developed new rehabilitation and reintegration initiatives to tackle the issue, most

have built on existing programmes, not specifically designed for foreign terrorist fighters

(Mehra 2016). This part of the paper explains how the states from the Western Balkans

are currently dealing with the issue of war travellers, looks at best practices from other

European countries and then elaborates on what should be done.

How are Western Balkan countries dealing with the issue of

foreign fighters?

Following the rise of IS worldwide, all governments in the region joined the

international efforts in fighting the trend. In accordance with UNSC Resolution 2178

adopted in 2014, the Western Balkan states amended their criminal legislation

recognizing participation in foreign conflicts as a criminal act. Kosovo has adopted an

entirely new law to address the issue, while the neighbouring states have added new

provisions to their criminal codes. The possible sentences are between 6 months and 15

years in prison for participation in a foreign war, recruitment of fighters or support for

terrorist groups (Beslin and Ignjatijevic 2017).

However, two key issues obstruct the course of justice. First, many war travellers

from the Western Balkans returned home in 2013-14 and, therefore, could not be prosecuted under the new legislation. Second, the implementation of the adopted

amendments has been extremely problematic, as the law has treated returnees as

terrorists, but prosecution often cannot find sufficient evidence of war travellers’ activities

in the battlefield (ibid).

In the last 18 months in Bosnia and Herzegovina, there were ten second-instance

verdicts, sentencing 16 people to a total of 30 years and 8 months in prison for going to,

trying to go to or returning from Syria and Iraq (Muslimovic and Rovcanin 2017).

Nonetheless, most indicted for going to the conflict in Syria received only one year in

prison due to guilt admission agreements (ibid). In Kosovo, most returnees have also

become objects of prosecution despite the denials of going to Syria to fight along IS

(Balkan Insight 2017). One example is the case of Albert Berisha who said that he travelled

to Syria to help the moderate Syrian opposition but was trapped by IS (Leposhtica 2016).

Once he returned to Kosovo, he set up an NGO to help other ex-fighters reintegrate

themselves into society: “The state has never understood that our goal was not to be

terrorists” (ibid).

Countries dealing with returning war travellers differ in the implementation of

rehabilitation and reintegration policies depending on:

1. Target audience (right-wing extremism, religious extremism)

2. Phase or setting of policy implementation (pre-prison, in-prison, postprison)

3. Voluntary or mandatory participation of targeted individuals

4. Who is responsible for the implementation (government, NGOs, or local

communities)

5. Policy components (psychological counselling, education, religious

counselling) (Van der Heide and Geenen 2017).

These components might help governments in the Western Balkans to adopt

measures which suit their local institutional culture. Experts believe that rehabilitation

and reintegration should start pre-trial, either in prison or in a local environment

(Veldhuis 2012). There are several “soft” approaches concerning prevention and

rehabilitation, which governments in the region can borrow from Europe. Looking at the

multi-stakeholder character of the policies, Reed and Pohl distinguish between three

options (Reed and Pohl 2017b).

The French top-down approach: The state relies on its representatives to decide

on a course of action for dealing with war travellers. This approach affirms that all relevant

stakeholders are involved in the process of de-radicalization. The so-called “Centres for

Prevention, Integration and Citizenship” opened in 2015 with the focus on deradicalization,

targeting individuals who travelled to conflict zones (ibid). However, these

centres seem to be inefficient since they encounter some administrative and practical

complications (Washington Post 2017).

The German bottom-up approach: The government financially supports local and

regional NGOs, which are responsible for the development and implementation of

prevention and rehabilitation initiatives. For example, the program “Hayat” established

in 2014 targets people involved in radical Salafist groups or on the path of a violent

Jihadist radicalization including war returnees from Syria and Iraq (Hayat Deutschland

2017). It includes an assessment of returnees and addresses both pragmatic and

ideological aspects of de-radicalization (Lister 2015). It engages family and members of

local communities who have a positive relationship with war travellers and can help them

in the process of reintegration. Local and regional NGOs usually stay closer to affected

individuals and communities and, therefore, can easily intervene.

Both approaches suffer from drawbacks (Reed and Pohl 2017b). In the French case,

local communities and families might be reluctant to report cases of radicalization due to

a fear of legal consequences as the Ministry of Interior runs the de-radicalization initiative.

In the German case, de-radicalization initiatives remain heterogeneous and lack a

comprehensive engagement of federal authorities, which in some cases might have

negative effects on coordination and unified best practices.

The Danish mixed approach: The so-called “Aarhus model” aims to build trust

between the authorities and the social networks to which radicals return (Guardian 2015).

This approach establishes networks involving schools, social services and police as well as

healthcare, prison and probation services. This institutionalized collaboration exists in

every Danish municipality (Reed and Pohl 2017b).

As the Western Balkan war travellers originate from certain geographical spots and

(usually) seek to return to the same places, a municipal approach to their reintegration

looks particularly relevant. Since mobilization has been concentrated in a number of

municipalities in each country, governments should focus on these hotspots rather

investing in de-radicalization campaigns at a national level. Following the Danish

example, the Western Balkan countries should consider three groups of measures:

individual risk assessment (based on motivation to go, motivation to return and

gender/age dynamics), reintegration and rehabilitation through work with communities

at a local level and addressing the push factors.

Recommendations

1) Recommendations on individual risk assessment

1.1 To tailor responses to returnees, governments should develop mechanisms to

identify precisely the individual motivations to join IS, motivations to return,

the gender/age dynamics and the commitment and risks posed by returnees.

Measures depend on several considerations. On one hand, some returnees may

not only be perpetrators but also victims of violence. On the other hand, some

individuals may support the radical ideology even though they were not

engaged in violent activities under IS. It might be useful to consider at least two

groups of war travellers (RAN 2017): (1) Returnees who were motivated to go

to Syria for humanitarian reasons. They are more prone to disillusionment,

arguably less violent and relatively free to leave the terrorist-held territory. (2)

Returnees who travelled to Syria or Iraq following the establishment of

“caliphate”. They have been battle-hardened and ideologically committed, had

to evade pervasive surveillance by IS to escape and may have come back with

violent motives (ibid).

1.2 With respect to male returnees, to consider criminal/war background. Various

sources confirm that almost one-third of those who have gone to Syria and Iraq

from the Western Balkans had violent experience (ICSR 2016, ICCT 2016, Europol 2016). Police records on the Bosnian contingent show that at least 44

of the 156 considered IS recruits have previous criminal experience, including

offences such as terrorism, illegal possession of arms and explosives, robbery,

and illegal trafficking (Azinovic 2015). Approximately 40% of those who left for

Syria from Kosovo also had criminal records before becoming war travellers

(KCSS 2015). Thus, returnees should be prevented from re-establishing their

criminal social networks.

1.3 With respect to female returnees, to consider their roles and duties on the

battlefield (being wives, mothers) but also if they may have been engaged in

different forms of violence or influenced by indoctrination

1.4 With respect to child returnees, consider age and attitudes (Van der Heide and

Geenen 2017). The age of the individual could give an indicator about his/her

role under the rule of IS. Children under the age of nine, born in the IS’ caliphate

or brought by their parents at a very young age, should be perceived as victims.

For children from nine to eighteen years old consider factors such as

indoctrination, training, and participation in combat activities as likely. The

latter group requires an approach, which goes beyond the victim-perspective.

Security experts should identify the degree of association of these children with

the IS’ culture and ideology. In addition, it is crucial to assess their attitudes

towards violence and IS, compared to adult returnees. Finally, consider that

juveniles are particularly vulnerable to mental, emotional and physical abuse

(ibid).

2) Recommendations on work with local communities (religious

communities, families or school communities)

Three types of communities should be engaged in the process of turning returnees

away from radical ideology and reintegration: (2.1) religious communities, (2.2) family

communities, and (2.3) school communities. The first task for local institutions is to

prepare each of these communities to be more receptive to the returning war travellers It

means to address challenges such as hostility, stigmatization and isolation that can

obstruct the process of reintegration (ICCT 2017).

2.1 The Western Balkan countries are post-conflict societies dealing with a variety

of identity crises and reconstructions. They experience an erosion of socio-cultural values and norms, where violence or retrograde ideologies are often

perceived as the only way for personal development and protection (Azinovic

and Jusic 2015). Post-conflict environments encourage the rise of identity

creation processes that have to construct the basis of foreign fighters’

mobilization. Hence, it is necessary to understand how ideological commitment

to radical networks appears and then is sustained in these societies. There is a

sufficient empirical evidence that many of the Western Balkan war travellers

who joined IS belonged to radical communities prior their departure. Radical

religious organizations and mosques, which promoted and encouraged radical

values, inspired many to leave for Syria and Iraq. For example, a significant

number of Bosnian war travellers and their families visited Salafist

communities or mosques operating outside the official religious institutions in

Bosnia and Herzegovina (Azinovic and Jusic 2015). On the other hand, a report

on Kosovo suggests that there is no firm evidence for radical ideologies being a

direct cause of foreign fighters’ mobilization (Kursani 2015). Although it is

impossible to determine to what extent affiliation to such structures affects

one’s decision to participate in a foreign conflict, the influence of these

authorities on mobilization seems significant at the local level. Consequently,

official religious institutions play an important role in the process of countermessaging

and reintegration of returnees. Some Western Balkan states already

started redirecting resources from fighting terrorism to de-radicalization

projects with a focus on both the prison population and local communities

where the released war travellers are returning to (Muslimovic and Rovcanin

2017). For example, the Islamic Community in Bosnia educates imams who

directly communicate with young people. Thus, religious communities should

be actively engaged in the process of reintegration and resocialization.

2.2 Families can be partners in the reintegration of war travellers. However, local

authorities should assess to what extent family members themselves support

extremist ideologies and would be supportive towards their radicalized relatives

(RAN 2017). In addition, events and social networks related to foreign fighter

mobilization may have affected families and social circles at the local level.

Authorities, therefore, should also consider psychological support for these

families. The goal is to prevent family environment conducive to future

involvement with radical groups.

2.3 School communities also play a vital role in the process of resocialization. They

have the difficult task to reintegrate returning children. Teachers, students, and

administration, therefore, should be prepared to contribute to this process.

Measures should be taken to educate teachers how to facilitate reintegration but

also to be able to recognize the dangerous behaviour. School communities

should also provide returning children with psychological support focused on

anger management or cognitive behavioural therapy (Mullins 2010).

Engagement in activities such as participation in sports, theatre, arts and music

may add value to the process of reintegration.

3) Recommendations for addressing push factors

IS war travellers from the Western Balkans often originate from a poor socioeconomic

environment. Once they return, they are exposed to the same conditions

including poverty and lack of employment opportunities. For instance, the empirical data

on Bosnia shows that most individuals who left for Syria between 2011 and 2015 come

from villages and small towns – they were poorer, unemployed, and less educated

(Azinovic and Jusic 2015). The link between poverty and terrorism has been widely

discussed in the literature. On one hand, the “absence of future” argument suggests that

factors like unemployment and economic inequality create a feeling of injustice and

deprivation, which might encourage individuals to get involved in extremist activities

(Abadie 2004). Some researchers argue that social welfare policies affect preferences for

terrorism by reducing poverty and inequality (Abadie 2004, Burgoon 2006, Krieger and

Meierrieks 2009). On the other hand, many scholars consider this claim problematic since

the behaviour of a small group of people cannot be directly linked to conditions that affect

a much broader segment of the society (Bjorgo 2005, Crenshaw 2011, Sageman 2008).

Although poor socio-economic conditions cannot explain the foreign fighter

phenomenon, they certainly affect the environment where radical networks emerge and

operate. A broad body of research on the link between poverty and radical views indicates

that poverty inspires larger numbers of people to deepen their religious belief and engage

in extremist religious-political activities (Barro and McCleary 2003, Berman 2000).

Empirical data on Kosovo indicates that previously poorly educated citizens in rural areas

attended lectures of Saudi charity organizations introducing them to more conservative

forms of Islam (Kursani 2015). Due to the lack of economic and political stability in these

regions, such organizations play the role of imperfect substitutes for social policies. Locals,

therefore, see them as a source of security and hope (Gill and Lundsgaarde 2004, Burgoon 2006). The absence of working welfare institutions in Bosnia or Kosovo leaves space for

religious charity organizations to influence more marginalized segments of the society

(KIPRED 2005). As they monopolized the social activism in these regions, citizens were

not able to refuse aid (Azinovic and Jusic 2015).

To sum up, “lack of future” factors might encourage returnees to again seek

engagement in radical activities. Consequently, poverty and unemployment are among the

push factors that local governments should address in dealing with the issue of returning

war travellers. Better job opportunities, employment programs, and improved welfare

policies play a vital role in reducing economic insecurity and inequality and might affect

preferences for re-joining radical networks. Reintegration of returnees should include

support in education, employment and housing.

Conclusion

Governments in the Western Balkans are under pressure to enhance security

measures to address the threat of returning war travellers. While applying “hard” policies

such as prosecution and detention solve the problem in the short term, they do not bring

a higher level of security in the long term. Thus, reintegration and rehabilitation measures

are increasingly important. To help radicalized individuals in rebuilding their lives back

home seems essential in discouraging their possible return to violence. Adequate risk

assessment, as well as complex “soft” policies, are necessary to reintegrate returnees into

the society. Institutions should also focus on the socio-economic conditions, which may

be conducive to radicalization and lead returnees again to seek violent solutions to their

problems. Governments should apply a tailored approach to every individual coming back

from the ranks of IS instead of acting on suspicion that they can conduct a terrorist attack.

Due to the relatively small number of fighters coming from each of the states in the region,

it is feasible to employ individual measures. However, the challenge for the authorities is

how to prioritize targets and to decide on the approach in each case. A mixture of topdown

and bottom-up reintegration measures might be a relevant approach to address the

problem in the Western Balkans. It includes a broad circle of stakeholders including

police, social services, local religious communities, families and schools. Governments

should consider country’s institutional culture when they adopt policies from other states.

Moreover, implementation of such policies should follow the geographical pattern of

foreign fighter mobilization in the region concentrated in hotspots in each of the states.

The issue of returning war travellers to the Western Balkans requires the attention

and efforts of the local governments but also the EU, and more specifically the EU states

from Central and Eastern Europe. The Bulgarian presidency of the Council of the EU

(which gives a priority to the integration of the Western Balkans) provides the Visegrad

Four with a good opportunity to engage more actively with the region.

Although the Central European countries have not experienced the issue of foreign

fighters, there are several ways to support the Western Balkan governments. First, to

support the dialogue among the countries in the region, with an emphasis on the KosovoSerbia

relations (put on hold after the assassination of the Kosovo Serb politician Oliver

Ivanovic). The Visegrad Four states should initiate a more intensive exchange of

information between police and intelligence agencies in the Western Balkans as well as

with the national security actors in the EU states. Second, Central European states have

the capacity to contribute to “soft” policies implementation with respect to the

reintegration of war traveller in the Western Balkans. The strong NGO communities in

these countries have experience and expertise, which might be applicable to the

reintegration efforts of the governments in the Western Balkans. Finally, Central

European states should consider direct investments in the region to help local

governments addressing the push factors for radicalization. ●