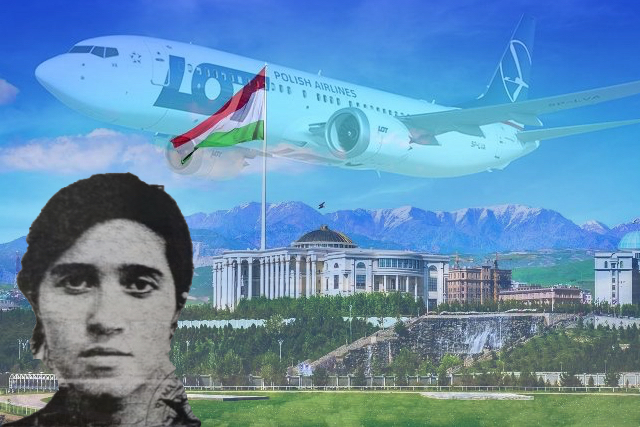

Belgian authorities are expected to make a decision soon regarding Tajik refugee Sitoramo Ibrokhimova. She will most likely be extradited to the Rahmon regime, as was her sister, 27-year-old Nigora Saidova, who was sent to Tajikistan along with her seven-month-old daughter on charges of aiding terrorism, which, according to The Insider, were fabricated. In her homeland, Saidova was sentenced to eight years in the worst women’s prison, where prisoners face rape and torture. Poland has been denying refugee status to Tajiks year after year — they are among the top three in terms of refusals, after Russians and Iraqi citizens. Emomali Rahmon uses the fear of ISIS to persecute entire families of emigrants – these can be both relatives of terrorists and relatives of oppositionists, but, as The Insider and the Polish weekly Polityka found out, European authorities do not really understand the case materials and often extradite citizens to Rahmon against whom the charges are obviously falsified. According to human rights activists, sometimes those forcibly returned are extradited to Russians: they are interrogated on the territory of the 201st military base near Dushanbe – tortured and forced to confess about ties to Ukraine.

Special operation to catch a dangerous criminal… in prison

In April 2024, the Polish Internal Security Agency published a press release boasting of a successful special operation to capture and deport a dangerous terrorist from Tajikistan, an ISIS militant hiding under false documents. No other details were given. The note about the security forces’ successes appeared immediately after the terrorist attack in the Russian Crocus Expo, for which the ISIS branch “Vilayat Khorasan” claimed responsibility, and citizens of Tajikistan were arrested. According to the Polish intelligence services, the captured perpetrator was connected to this cell.

However, they kept silent about the fact that the “hero” of their special operation had already spent two years in a Polish prison by that time. 31-year-old Usmon Shamsov ended up there trying to escape the war in Ukraine and persecution by the Tajik regime in Poland, The Insider and the Polish weekly Polityka learned. Fearing extradition to Tajikistan, he entered Poland using a fake driver’s license in the name of Usmon Aliyev. Two years after his arrest, trials, and appeals, Polish security forces sent him back to his homeland, where prison awaited him. A year before, Shamsov’s wife, 27-year-old Nigora Saidova, with a seven-month-old child in her arms, was sent from Poland to Dushanbe from Poland, despite the court’s decision on extradition and without any publicity.

How Nigora Saidova’s case was fabricated

Nigora Saidova went through a pretrial detention center, prison, prison hospital and closed refugee center in Poland. She was detained on February 28, 2022, at the Medyka border crossing, where she arrived from Ukraine with her sister Sitoramo Ibrokhimova, her husband and children, fleeing the Russian invasion. It turned out that Tajikistan had put Saidova on the Interpol wanted list on charges of mercenarism. Nigora, who was seven months pregnant, was separated from her husband and two children (aged two and three).

Materials reviewed by The Insider and Polityka showed that Tajikistan’s charges against Nigora Saidova were falsified. According to Tajik investigators, on March 23, 2018, Saidova flew from Dushanbe to Istanbul, and then, on the advice of her sister, came to Syria, married a member of the Islamic State and became an active participant in it.

In fact, Nigora and her sister Sitoramo had been living in Ukraine since January 12, 2018. The date of Nigora’s border crossing was confirmed by two sources in the Ukrainian special services. They also said that Nigora did not leave the country again until the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. This is also confirmed by the border stamp in Sitoramo’s passport – the sisters arrived in Ukraine together.

Saidova also could not have married an Islamic State militant in Syria. She married taxi driver Usmon Shamsov (they entered into a religious marriage, nikah) on April 6, 2018 in Kyiv (The Insider has a copy of the marriage document). Shamsov himself had been in Ukraine since 2016 and left there with Nigora and their children only in February 2022.

It is also unlikely that Saidova would have entered areas controlled by the Islamic State in Syria in March 2018 via the Turkish border. By that time, ISIS had been largely defeated and occupied only two small enclaves in the south of the country, far from the border. To reach ISIS at that time, Nigora would have had to travel through territory occupied by other, hostile groups.

The charges against Nigora Saidova were drawn up very carelessly by Tajik security forces, and it followed that she committed all of her “crimes” within one day – March 23, 2018. In addition, a large number of mistakes were made during the trial of Nigora Saidova: first by the border guards during the interrogation, then by the Polish prosecutor and the court.

According to the charges against Nigora Saidova, she committed all the crimes within one day – March 23, 2018.

Despite all this, Nigora Saidova was arrested and held for several months. She was unable to communicate with others or defend herself, as she was not provided with a Tajik translator. Prison staff tried to understand her using an electronic translator. Nigora wrote in broken Russian, in which she could barely formulate the simplest requests for the prison guards:

“I ask for a meatless diet because I don’t like it. I can’t eat meat, thank you, Saidova Nigora.”

The documents show that the pregnant Saidova suffered from anemia. As a Muslim, she apparently did not eat meat, fearing that it might be pork.

According to the materials of Saidova’s case, reviewed by The Insider and Polityka, the court hearings were quick — some lasted five minutes — and most often took place without her participation. Requests for asylum were ignored.

According to Piotr Sura, the lawyer-assignee who defended Saidova, the number of extradition hearings increased sharply in early 2022 due to the huge influx of people at the border crossing point following the Russian invasion. The young woman “fell into the millstones of the machine.” In addition, accusations of involvement in terrorism worked against her. It would seem that an extradition request coming from a country where human rights are regularly violated should have raised concerns and become a signal that this case needs to be examined especially carefully. However, in Saidova’s case, everything was the opposite: Polish officials cooperated with investigators from Tajikistan with genuine zeal. For example, the materials include correspondence between Barbara Rzuchowska (International Cooperation Department of the National Prosecutor’s Office) and Manuchehr Makhmudzoda (Head of the Foreign Economic Cooperation Department of the Prosecutor General’s Office of Tajikistan). Rzhukhovskaya was nervous that Saidova’s term of detention was coming to an end and the pregnant woman would soon have to be released, and therefore asked that the court urgently be provided with the documents necessary for extradition. She even helped her Tajik colleague by recommending the wording for the letter so that it would be accepted in court.

In prison, Nigora Saidova wrote letters full of despair, addressed to the prosecutor, the court, and sometimes to no one at all. Almost all of them remained unanswered:

On April 26, 2022, the prisoner gave birth to a daughter, she named her Rabiyya (spring). Ten days after the birth of the child, Nigora wrote a letter again: “Please release me so that I can find my husband and children.” “We have no information about your husband’s stay with the children,” the court replied. This despite the fact that Nigora Sitoramo’s sister, who remained with her children, was looking for her through the Red Cross, and Nigora’s husband was imprisoned in Poland.

In June 2022, the court in Przemysl drew attention to the number of errors in the Tajik indictment documents and considered that it was impossible to make an extradition decision on their basis. It asked the Tajik prosecutor’s office to supplement the application, but the documents took a very long time to arrive, the detention period expired, and Nigora’s arrest was lifted. However, immediately after the official release, the woman and her baby were detained by border guards and placed in a guarded refugee center in Kętrzyn.

“In my experience, courts often mechanically approve Border Guard applications,” says Zuzanna Kačiupska, a legal adviser who works with the Association for Legal Intervention. She noted that people should not be placed in the center if it could pose a threat to their health or life. This was true for the mentally exhausted woman and her two-month-old daughter.

When Saidova, who had recently given birth to a child, ended up in a refugee center, the border service decided to deport her. Unlike extradition, deportation in Poland, as in other EU countries, does not require a court decision. It is an administrative case. Several reasons were given as grounds: Saidova does not have a visa, has no means of support, and her presence in the country could pose a security threat. Nigora and her seven-month-old daughter Rabiyya were deported on October 19, 2022, on a regular flight. In Dushanbe, the woman and child were handed over to Tajik security forces. The Polish border service did not answer any questions from The Insider and Polityka about Saidova.

Rabia’s fate is unknown, and Nigora was sentenced to eight years in prison. She was placed in the only women’s penal colony in the city of Nurek. She was banned from all communication with the outside world: letters, calls to relatives, visits – her relatives do not even know if she is alive. Finding a lawyer who would undertake to visit a prisoner with such an accusation is almost impossible in Tajikistan. Former prisoners describe the colony where Nigora was sent as “hell on earth.”

Nigora was sentenced to eight years in prison. She was banned from any communication with the outside world: letters, calls to relatives, visits

“I’m afraid of torture and I’m afraid of being raped”

Nigora’s sister Sitoramo Ibrokhimova is currently in a deportation prison in Belgium, where she is proving her innocence in a similar case. If she fails, she could share Nigora’s fate. Sitoramo has four children of his own and Nigora’s two daughters to look after.

Human rights activists and her lawyers are trying to prove her innocence and the risk of torture in her homeland. The story of Nigora, who was extradited by the Polish authorities, can help prevent the same tragic injustice against her sister.

Sitoramo Ibrokhimova, like her sister Nigora Saidova, was on the Interpol red list at the request of the Tajik authorities. On the day of Nigora’s arrest in Poland, Sitoramo was lucky: the border guards, when sending the application to Interpol, made two mistakes in the woman’s surname in Latin letters, and the warning system did not work.

There are also many inconsistencies in Sitoramo’s case, which the Belgian authorities may still take into account and prevent her extradition to her homeland. The Insider and Polityka have access to the materials of her case.

According to the documents, Sitoramo, then a mother of three children born in 2011, 2012 and 2015, traveled to Turkey with her children in 2016 to join ISIS militants, underwent combat training at an ISIS camp and took part in military operations in Syria with weapons in hand.

Sitoramo’s documents, passport stamps, records in the Ukrainian border database and the case materials of her husband Murodali Khalimov paint a completely different picture. Sitoramo came to her husband in Turkey on February 1, 2016, but four months later she was left alone with her children, the youngest of whom was barely a year old. Murodali Khalimov left for Ukraine and was going to return for her later, but on June 26, 2016, upon arrival, he was detained at the Kharkiv airport, where he immediately asked for political asylum.

He was jailed for a year due to an extradition request from Tajikistan, but was later released and remained in Ukraine. Eighteen months later, on January 12, 2018, Sitoramo flew to her husband with her children and sister Nigora.

“My husband was kidnapped in 2018 in Ukraine, near our home, in front of my eldest son Mohammed. He was sent to Tajikistan and convicted without a fair trial, without testimony, without evidence. He was sentenced to 23 years in prison. I don’t know what’s happening to him now,” Sitoramo said during her interrogation for asylum in Belgium.

I am also on the blacklist, if I get there , I am very afraid of torture. Women are treated cruelly in prison. I am very afraid that I will be raped. <…>

In 2019 or 2020, my parents were threatened, demanding that they force me to go back. I am very afraid to go back there. I would like to be able to study and earn a living. Now I am responsible for six children.”

A member of the family of an enemy of the people

The charges against Nigora Saidova and Sitoramo Ibrokhimova were apparently fabricated by the Tajik authorities because of their family ties. Tajik security forces have been persecuting the entire family of Sitoramo’s husband Murodali Khalimov for many years. In total, they have managed to imprison or kill more than 15 family members. During the asylum interrogation, Sitoramo Ibrokhimova told the Belgian authorities that the problems began in 2015 because of her husband’s brother, Khuchbart Khalimov:

“His brother denounced the regime. He was unhappy that we lacked rights, laws. <…> My husband’s brother never preached Islam. He was accused of preaching Islam, and also of being an extremist and a terrorist. All these accusations are false. As a result, his other brothers and two nephews, one of whom just turned 18, were arrested one after another.”

In 2018, Tajikistan succeeded in extraditing Sitora’s husband Murodali Khalimov from Ukraine. It looked like a kidnapping: four unknown men dragged Murodali into a car in front of his young son and drove away. This was preceded by an information campaign to discredit him, which began with the publication of Radio Liberty’s Radio Ozodi project. Journalists broadcast the version of Tajik security forces, who accused Khalimov of having ties to ISIS and claimed that he fought on the side of Ukraine in the “DPR”. At the same time, the authors of the article referred to the testimony of a person arrested by security forces.

It is interesting that the ISIS version did not appear immediately; in the early materials of the criminal case, the Tajik authorities accused Khalimov of participating in the organization “Jamaat Ansarullah.” The case materials are at the disposal of The Insider and Politika. “Jamaat Ansarullah” is the Tajik political opposition to the Rahmon regime; the organization consists mainly of Tajiks and considers itself to be part of the Taliban. In subsequent accusations by Tajikistan, the accusation of Khalimov’s relatives of their connection with ISIS looks unconvincing, because “Jamaat Ansarullah” is an ideological opponent of ISIS. As the leader of the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan, Mukhiddin Kabiri, explained in a conversation with The Insider and Polityka, it is often more convenient for the Tajik authorities to present members of “Jamaat Ansarullah” and other associations as supporters of ISIS, because this “makes a more negative impression on Europeans.”

Torture at the 201st Russian base

According to Ukrainian human rights activist, head of the Ruka Dopomogi Foundation Anvar Derkach, after being extradited to Tajikistan, Khalimov was tortured at the Russian 201st base, located near Dushanbe. They beat testimony out of him about the alleged ISIS training camps located in Ukraine, a fake about the existence of which Russian propaganda has been actively spreading since 2016. Mukhiddin Kabiri said that he knows about the torture of Tajiks who had been to Ukraine at the 201st base:

“Russian security forces have set up a joint headquarters with Tajik ones, and Russian investigators are working in Tajikistan. If someone ends up in a Tajik prison, Russian security forces will have access to them if the person is somehow connected to Ukraine. They interrogate people from Poland, Ukraine and the Baltic states. Some Tajik, after being tortured, says that ISIS members were trained in Ukraine, then this is spread through Tajik internal channels in Russian and Tajik, and part of the population believes it.”

“Our relatives are hostages”

The practice of persecuting people not for specific crimes, but for their belonging to the families of opposition members, is widespread among Tajik security forces, notes human rights activist Anvar Derkach. Mukhuddin Kabiri also says this: “The families of opposition members are hostages of the regime in Tajikistan. Collective responsibility fits into the logic of power.”

“Imagine the torment that an oppositionist in Tajikistan goes through,” Kabiri says. “It’s very difficult to explain to European officials. My ninety-year-old father flew to his grandchildren, but they took him off the plane and interrogated him, mocked him, called him the father of a traitor. He was already sick, and they hastened his death. My older brother has not been allowed to use the Internet or a telephone for seven years, and he has to register with the police every week. They did not want to let my four-year-old grandson with cancer go to Turkey for treatment. Our relatives are hostages.”

Kabiri himself was also wanted by Interpol on a “red notice” for alleged Islamic terrorism. “Many of my opposition colleagues are still on Interpol’s lists,” he says.

“Europe is very sensitive to Islamic terrorism and radicalism, so they [Tajik authorities] accuse all their opponents of Islamic extremism and terrorism. Ordinary police officers or those who deal with migrant issues, they are not all experts and do not know what kind of party we have. They just say: ‘Better to be on the safe side. Why should I figure out who is who? Here is the list. Tajik authorities say that they are accused. Let’s get rid of them all.'”

The Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan was banned only in 2015, before which it took part in elections on an equal basis with Rahmon’s People’s Democratic Party. Now, Tajiks who are unpopular with the regime cannot count on “the same treatment as oppositionists from Russia or Turkey, or even Iran and Afghanistan,” he laments.

“I meet with European politicians and officials and try to explain the situation, and I wonder why they have one attitude, for example, towards the Belarusian opposition, but they are very soft towards Rahmon’s actions. And they say: ‘Because Rahmon is not a problem for us and not an opponent. He is fighting against the Taliban. He is a dictator, but he defends secular values, he is against religious radicalism.’ And all our attempts to explain to European politicians that they should avoid double standards and should use a single criterion in relation to all migrants are useless.”

In addition to Interpol persecution, the Rakhmon regime can also use other mechanisms, such as adding people it doesn’t like to the financial monitoring lists that are taken into account by banks in all European countries. For such people, even those who have received refugee status in Europe, it is extremely difficult or impossible to open a bank account, and therefore, to legalize their lives, says Kabiri.

According to human rights activists, the situation with deportations of Tajik citizens is approximately the same in all European countries. Poland refuses refugee status to Tajiks year after year – they are ( 1 , 2 ) in the top three in terms of refusals, after Russians and Iraqi citizens. Despite the fact that, unlike the former, the number of Tajiks asking for political asylum barely exceeds 100 people per year.