Abstract: The fall of the Islamic State’s caliphate in Iraq and Syria significantly impacted the group’s ability to fundraise through territorial control. Despite this loss, the group retained substantial financial reserves, estimated between $10 million to $30 million, some of which were stored outside its immediate area of operations. These funds have enabled the Islamic State to sustain and expand its global network of provinces and sub-groups, primarily in Africa and Asia, through the General Directorate of Provinces and by providing start-up and sustenance funds to its various sub-groups. This article provides an in-depth analysis of the Islamic State’s financial strategies post-caliphate, illustrated through case studies of various Islamic State provinces and sub-groups and their financing mechanisms. The Islamic State’s evolving global strategy and financial strength is a challenge for international efforts to combat the group’s persistent and adaptive financial network. The article concludes with a discussion of the implications for global security.

The fall of the Islamic State’s caliphate in Iraq and Syria in 2019 marked a profound loss of territory for the group. Prior to this, the Islamic State was a wealthy terrorist group that relied on a variety of methods to raise funds, many of which were based on territorial control. As a result, the Islamic State’s loss of territory was a blow to its fundraising capabilities. Still, the group did not lose all of its wealth: It managed to store a significant amount of money outside its immediate area of operations,1 with estimates ranging from $10 million to $30 million.2 These funds have allowed the group to create, sustain, and augment provinces and sub-groups around the world, concentrated mainly in Africa and Asia, in a globally integrated network.3 The Islamic State has focused on establishing and managing a global presence through its General Directorate of Provinces (GDP).4 Part of this focus has been on developing financial networks and self-sufficient funding strategies, which has created resilience and redundancy in the broader Islamic State brand that is difficult to combat, particularly in the face of competing global security priorities. The 2024 threat environment, which has seen a steady stream of arrests and disruptions of Islamic State activities, illustrates how this network has maintained the group’s resilience and, in some cases, grown stronger since the fall of the caliphate five years ago.

This article’s analysis draws on case studies of the various Islamic State provinces and groups and their known financing mechanisms and methods. Academic and open-source research is augmented by information from the United Nations Security Council’s monitoring team and interviews with regional experts conducted by the author. By combining this disparate research, a new picture of the Islamic State’s global strategy and financial strength comes into focus, and it points to a grim future for efforts to combat the group’s international presence.

Islamic State Finance

In its heyday, the Islamic State was able to raise significant amounts of money (perhaps as much as $1 million per day) from the territory that it controlled in Iraq and Syria.5 The group did this by extracting and selling oil, taxing and extorting the population under its area of control through kidnapping for ransom, the theft and sale of antiquities, and many other methods, all to supplement the cost of its ongoing war and to implement its political project.6

Not all the money raised in Iraq and Syria was profit; running the caliphate cost the group serious money. The Islamic State provided some security and other state and governance functions in the territory it controlled and had to pay individuals to provide these services.7 In practice, while the group ran a surplus and diverted some of those funds out of Iraq and Syria, the costs of running the caliphate likely consumed most of the revenues generated. Despite this, the group generated a surplus of funds and stored much of those financial reserves in cash. However, upon dissolution of the caliphate, the group likely lost access to much of its surplus funds, although resources outside Syria and Iraq remain accessible.8 For instance, financial networks and resources in Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and Sudan9 remain largely intact, despite U.S. sanctions and Turkey’s arrests of Islamic State operatives.10

Indeed, the Islamic State was able to siphon some money out of Iraq and Syria and establish a fund for its longer-term objectives, including the establishment and funding of the GDP and other Islamic State groups. From 2014 onward, the Islamic State invested funds in legitimate commercial businesses such as real estate and automobile dealerships.11 The bulk of the group’s residual and liquid assets are reported to have been transferred to Turkey, some in cash but a portion in gold.12 The group probably also moved funds to different locations internationally through one of its finance networks, such as the Al-Rawi network.13

Today, the remnants of Islamic State Central operating in Iraq and Syria are estimated to have access to between $10 million and $20 million in liquid assets, including cash.14 While this is significantly less than what the group previously held, it is plenty of money for the low-level insurgency/periodic terrorist attacks that the group perpetrates in its current areas of operations. These funds are also likely sufficient to occasionally provide influxes of cash to its provinces and sub-groups that provide start-up and short-term funding to help maintain its global brand. This brand combines provinces, sub-groups, networks, and identity-based support networks,a all connected by a financial network.

Islamic State Provincial Finance Strategies

Key to the Islamic State’s ongoing global relevance are its provinces and sub-groups, which operate primarily in Africa and Asia. In 2014, the group established the GDP to ensure its core leadership’s ability to maintain command and control over the new entities pledging allegiance to the Islamic State.15 Over the next nine years, the Islamic State established relationships with groups in many countries, ranging from loose connections to formal recognition of provinces. Over time, these connections have waxed and waned. Still, a presence remains in Libya, Algeria, Egypt, West Africa, Somalia, Mozambique, South Africa, Nigeria, the Sahara, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, Yemen, Pakistan, the Caucasus, Afghanistan, and Southeast Asia.16 In many of these cases, the Islamic State welcomed into its fold groups that existed before the rise of the Islamic State’s global brand. And in some of these cases, these groups had existing sources of funds and established financing methods.

Islamic State provinces and sub-groups employ a common finance strategy dictated by the economic and financial terrain in which they operate; the precise nature of the finance strategy also tends to reflect the size and strength of sub-groups. Islamic State provinces and sub-groups seeking to control territory implement a taxation system like what the group deployed in Iraq and Syria. This is by design: The Islamic State has even deployed financial advisors to professionalize some of the fundraising activities in its provinces and sub-groups, such as Mozambique,17 Nigeria,18 and Somalia.19

The deployment of advice and funding was part of the Islamic State’s strategy from the first instance. For example, in 2014, the Islamic State established a group in Yemen with leadership, direction, and financing from Islamic State Central.20 This was a direct effort by Islamic State Central to implement economic and financial lessons learned in Iraq and Syria. These lessons are also being implemented to make the provinces more sustainable in the long term, prioritizing independent revenue streams and reducing the provinces’ burden on the broader movement.21

This finance strategy generates significant money. For instance, Islamic State-Somalia is estimated to raise at least $6 million annually.22 While nowhere near the sums raised by the Islamic State in its heyday, Islamic State-Somalia is a much smaller organization, and these funds are likely ample to support its ongoing activities, as well as the Al-Karrar office, the GDP’s presence in Somalia. The DRC-based Islamic State affiliate ADF was provided with some funding through Islamic State networks in Somalia and East Africa;23 now, the group relies on taxing and extorting local businesses, as well as theft and kidnapping for ransom.24 Other groups, such as Islamic State-Mozambique (known as Ansar al-Sunna or, confusingly, al-Shabaab), have also adopted these models.25 Islamic State-Mozambique relies on taxation of business activities (small stores and sole-proprietor transportation providers) to generate revenues and, in some cases, uses these business activities to provide cover for its members.26 Some provinces, such as Islamic State-West Africa Province (ISWAP)27 and Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP),28 as well as smaller cells, such as the one operating in South Africa, employ kidnapping for ransom and robberies to raise funds.29 This is critical for the Islamic State’s broader longevity: Having its local sub-groups and provinces be largely self-sufficient and developing diversified fundraising schemes makes the broader movement more resilient to counterterrorism pressures.

By 2017, the Islamic State had established more provinces/franchise groups in Libya, Egypt (Sinai), and Southeast Asia.30 While much depleted in terms of overall importance in the group’s finance network, Islamic State-Libya continues to be resilient, exploiting the local political crisis and economic decline in the south while maintaining cooperation with tribal elements involved in smuggling and illicit trade, which attract new fighters. The group finances itself from arms smuggling in southern Libya, taxes on illicit trade routes, and kidnapping for ransom, in addition to small and medium-sized enterprises in Sahel towns run by its sympathizers (from which funds are likely diverted in the form of donations), especially in western Libya.31

Islamic State affiliates in Southeast Asia also generate revenue locally but with less success than other provinces and sub-groups, with some exploiting the charitable sector to raise funds for terrorist activities in Indonesia.32 The Islamic State in the Philippines raises funds and uses the formal financial sector to transfer state-backed currencies. However, it has increasingly used cryptocurrencies to move money internationally.33 As of 2023, the United Nations assessed that Islamic State-SEAP (Southeast Asia province) relied heavily on Islamic State Central funds for attacks and propaganda activities.34

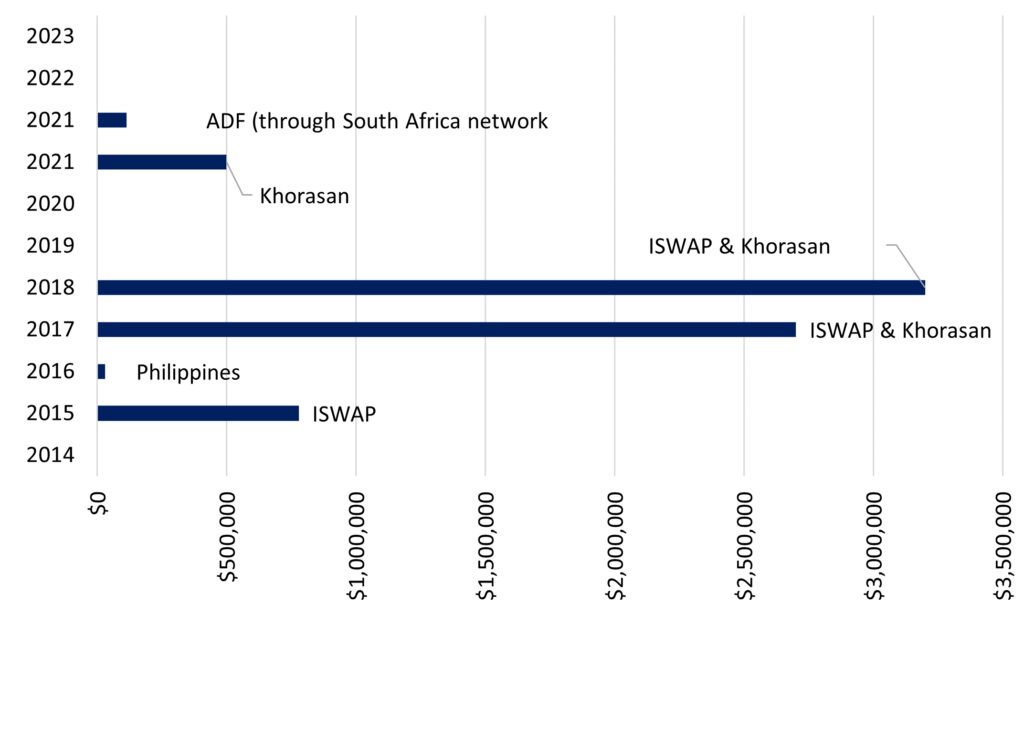

Centralized fund transfers from Islamic State Central have been instrumental in providing some provinces and groups with start-up funds and, in other cases, funds to sustain their activities during economic drought. This has been important, particularly in areas where the group has experienced between-group conflict or has struggled to establish non-taxation-based revenue streams, a prerequisite for which is territorial control or, at the very least, significant influence. For instance, Islamic State-Libya received millions (the precise figure is unknown) in start-up funds from Islamic State Central in 2014, and while this funding dwindled between 2016 and 2019, regular transfers resumed in the early 2020s.35 Over the last 10 years, Islamic State Central has also transferred millions of dollars to various provinces and groups, particularly ISWAP and ISKP, the group’s strongest outlets today. While details released by the U.N. monitoring team and other open sources about Islamic State financial transfers is unlikely to be exhaustive (and specific information on the amount of money sent to Islamic State-Libya is not available), this information provides a snapshot of the level of funding that Islamic State Central has sent to the provinces and sub-groups, illustrated in Figure 1.36

East and Central African provinces of the Islamic State also received transfers from Islamic State Central in 2017 (amounts unknown), which allowed the groups to expand their operations.37 Islamic State Central Africa Province or ISCAP (the province composed, at the time, of the ADF and Islamic State-Mozambique) is believed to have used some of these additional funds for attacks, purchase of supplies, and recruitment.38 While Islamic State Central financing has been critical in increasing and sustaining some groups’ operations and capabilities, local funding streams sustain the groups and provinces. Domestic financing capability is critical for many of these groups, as reflected by the fact that this strategy is replicated throughout Islamic State provinces and groups and the importance that Islamic State Central places on this strategy by deploying financial advisors.

Islamic State Finance Networks

Beyond the formal provinces and sub-groups, Islamic State finance networks, both regional and international, operate independently and play a crucial role in the broader financial facilitation network. These networks are essential for sustaining the movement’s operations and vary in their connections to Islamic State Central; some are tightly integrated with the brand, provinces, or sub-groups, while others are opportunistic nodes driven by profit. Key networks include the Al-Rawi network, the South Africa network, and the brand’s presence in Turkey and Sudan. Other identity-based support networks have also emerged in diverse locations, such as the Maldives, further highlighting the complexity and reach of the Islamic State’s financial infrastructure. These networks enable the group to maintain financial resilience and operational continuity.

The Al-Rawi network operates in Iraq, Turkey, Belgium, Kenya, Russia, and China and was used by the Islamic State to transfer funds.39 The network uses proxies and cash smuggling to obfuscate the source of Islamic State money and has also converted funds into gold.40 The network is primarily a family business. The leader of the network, Mushtaq Al-Rawi, was responsible for resurrecting a prominent money laundering network that was active during Saddam Hussein’s regime.41 The network uses cutouts (proxies), layering, and cash smuggling to obfuscate the source of Islamic State money.42 Individuals in the network have accepted Islamic State cash (hundreds of thousands of dollars in regular transactions totaling millions of dollars), converted those funds into gold, and then sold the gold and reverted the proceeds to cash for the Islamic State (a somewhat familiar money-laundering scheme).43 Much of this network likely remains in place despite U.S. designations, arrests, and deaths of key members.44

The South Africa node of the Islamic State’s network in East and South Africa has provided funds to various groups and actors. For instance, the DRC’s ADF network was directly involved in money transfers from South Africa.45 Further, in 2022, the U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned seven Islamic State financial facilitators in South Africa for providing support and funds to the Islamic State in Mozambique,46 and South Africa-domiciled banks were used to transfer funds from the GDP (likely the Al-Karrar office in Somalia, or Al-Furqan in Nigeria) to the Islamic State in Central Africa (ADF and Islamic State-Mozambique).47 While these networks might have been disrupted through a combination of U.S. designations and South African law enforcement action,48 the long-term effects of these counterterrorism efforts have yet to be demonstrated, with both Islamic State-Mozambique and the ADF demonstrating significant operational tempos in 2024 that do not suggest a lack of funds.

Other areas of Islamic State operations also contribute to the network. For instance, an Islamic State member, Abu Bakr Al-Iraqi, a businessman, had registered a variety of businesses using false identities in Sudan and Turkey. According to information published by the United Nations, “he operates several money exchange businesses and a travel/tourism agency in Türkiye and holds substantial investments in the Sudan.”49 This appears to be more of a facilitation network than an active operational group, at least currently.50

In other cases, Islamic State supporters might raise funds individually for the group; these are unlikely to be heavily coordinated fundraising campaigns and are instead identity-based support networks and individuals seeking to contribute to the cause. For instance, the June 2024 arrest of an individual in Germany for, in part, transferring nearly US$1,700 in cryptocurrency to an address associated with ISKP51 illustrates this support. These parts of the network are informal groups of individuals who (sometimes) band together to contribute to financing an organization or operation to feel connected to a cause and to feel they are providing it with support.52 While these nodes in the network are often small, they can be impactful, particularly when they mobilize to finance a terrorist attack directly or when the central group uses them to move money for operational purposes.53 Another more pronounced example of this type of activity is the finance network that has arisen in Tajikistan and among Tajik Islamic State supporters,54 funds from which might have been used for the Moscow Crocus Hall terrorist attack.55 Because of the dispersed nature of this network, most people sending funds are unknown to law enforcement and security services, which makes stopping the movement of money in advance of attacks or incidents challenging.

The Al-Karrar Office

The networks that facilitate the movement of funds between various groups are well-developed, and they appear to be coordinated in large part by the Al-Karrar office located in Somalia. Recent reporting on the Al-Karrar office illustrates this point: The office created links between different Islamic State provinces across Africa, including the DRC and Mozambique, and throughout the Middle East, using a network of businesses allegedly run by the Ali Saleban clan in Somalia.56 Al-Karrar has also been central in exporting the Islamic State’s extortion and taxation business model, including to Mozambique.57

Interestingly, the flow of funds between Islamic State Central and the provinces is not one-way. Some groups also share a portion of their profits back to the Al-Karrar office, either as payment for the advice they have received or as part of an ongoing and concerted effort to fund the office.58 In an article for this publication last year, Tore Hamming found that funds flow partly from the provinces to the center.59 Hamming further found that “50 percent of funds was required to be allocated for smaller provinces associated with a specific larger province, 25 percent for the general administration of larger provinces, and 25 percent to the Islamic State’s Bayt

al-Mal [central bank].”60 Even smaller groups, such as Islamic State-Libya, have supported other groups. In 2015, one individual from Islamic State-Libya is believed to have transferred money, weapons, and ammunition to Islamic State-Sinai and potentially to ISWAP as well.61 This division of funds might help explain the spread of Islamic State-affiliated jihadi groups across Africa and explain what some wealthier groups are doing with their financial surpluses. The redistribution of assets across the network indicates a finance cycle in which advisors and funds are deployed to help establish or formalize a province’s fundraising structures (specifically taxation). Then, some funds are remitted as payment to the Al-Karrar office and Islamic State Central. This cycle enables Al-Karrar to provide ongoing support to the provinces, establish new ones, and sustain the Islamic State in Syria.

The role of Islamic State-Somalia in funding the Al-Karrar office is likely an important one. Islamic State-Somalia has a relatively small presence in the country and a relatively limited operational tempo. As such, the group likely has limited expenditures in Somalia, meaning it could provide surplus funds to other groups through the Al-Karrar office. If this is the case, the Al-Karrar office likely has access to much, if not most, of the funds raised by Islamic State-Somalia, currently estimated to be around $6 million per year.62 These funds could create more resiliency in the network and provide funds for other groups to become established or to increase their operational tempo.

According to U.N. reports, some member states reported that the financial strength and importance of the Al-Karrar office is overestimated and that the Al-Furqan office raises more funds than Al-Karrar.63 While this latter point is likely valid, it appears that Al-Karrar plays a more central role in facilitating the movement of funds through the network, even though Al-Furqan in Nigeria might have more money at its disposal. This likely has to do with Somalia’s financial network. Over time, Somalia has developed an impressive network of mobile money operators and hawalab that can move money quickly and cheaply worldwide.64

While Al-Karrar and the Islamic State finance network are important, they do not sustain Islamic State sub-groups. Instead, money received from the network is better thought of as start-up or seed funding meant to help groups get established or overcome temporary financial difficulties. The Al-Karrar office’s primary influence in the longer term is through the deployment of advisors and the establishment of the Islamic State finance strategy in the provinces and sub-groups. The office likely also functions as a logistics and financial hub for the network, a critical role for the brand but not necessarily essential for revenue generation.

The Islamic State’s Growing Adoption of Cryptocurrency

Globally, terrorist groups have increasingly used cryptocurrency in recent years to move funds internationally, and the Islamic State is no exception.65 However, this is not to say that they have abandoned traditional methods of moving funds, quite the opposite. Islamic State Central primarily relies on hawala and cash couriers. However, it has also used trade-based methods of moving funds across borders, particularly in Nigeria and Mozambique.66

Central Asian jihadis exemplify the diversification of fund movement sources well. They solicit donations from identity-based support networks and receive funds through online payment systems and cryptocurrencies, as well as through more traditional mechanisms such as QIWI Wallet, Western Union, Ria, and online bank transfers.67 The East and South Africa network, controlled by the Al-Karrar office, primarily uses cash and hawala to move funds.68 The network also uses money service businesses, banks, mobile money, and some cryptocurrency transactions to move funds globally.69 This diversification of methods demonstrates that the Islamic State is mechanism agnostic: The group and its supporters will use whatever fund transfer mechanism is fastest, cheapest, and least likely to be detected and disrupted.

Islamic State provinces and sub-groups are not the only ones using cryptocurrency; identity-based support networks also use it. In the Maldives, supporters have raised and sent money through cryptocurrency to wallets associated with the media units of ISKP and Islamic State-Pakistan.70 These funds were raised through a network of approximately 20 people and included corporate fronts.71 Other Islamic State supporters have also been sanctioned for providing Islamic State leadership and supporters with cybersecurity training and enabling the group’s use of cryptocurrency and obfuscation methods meant to hide the source and destination of the funds. 72 For terrorists operating in small countries or outside of areas where the Islamic State has a significant presence, cryptocurrency might hold even more appeal than other methods of moving money since they can avoid interacting with compliance staff or having their transactions caught up in geographic targeting and monitoring.73

Some Islamic State provinces and sub-groups are more prone to using cryptocurrency than others. ISKP is one such example. The group has used Tether to receive funds,74 and recent attacks and arrests suggest a broad use of cryptocurrency by the group and its supporters.75 Some of these funds are believed to transit through virtual asset exchanges in Turkey,76 where ISKP can convert cryptocurrency into cash and other monetary instruments with relative ease and impunity.

Not all Islamic State theaters have adopted cryptocurrency use. For instance, Islamic State groups operating in Nigeria, Mozambique, and the DRC have minimal, if any, adoption of cryptocurrency. There are some reports that ISWAP has made payments using virtual assets through Tether,77 but such reporting is limited. For Nigeria, this is counterintuitive, as the country is ranked second in the world for cryptocurrency adoption.78 Because of this, one would expect to see more use of cryptocurrency by ISWAP. However, since ISWAP is regionally concentrated and much of its revenue generation is done in cash (through taxation and extortion), it stands to reason that it has little use for cryptocurrency. It also suggests that the GDP office there, Al-Furqan, is not responsible for or integrated with the broader financial facilitation network. However, the possibility also exists that law enforcement and security services have failed to identify cryptocurrency transactions associated with the Islamic State originating in or going to ISWAP/Al-Furqan. While possible, this scenario is less likely given the extensive analytic capabilities that have been deployed to analyze blockchain transactions and identify terrorist-associated wallets.

The case of Afghanistan and ISKP is also intriguing. While Afghanistan is not high on the index of crypto adoption, hawaladars in the country have been relatively quick to adopt cryptocurrency as a service, and proximity to India and Pakistan, both very high crypto-adopting countries, likely further facilitates this adoption. Hawaladars set up wallets to receive transfers of funds through cryptocurrency and essentially act as informal cryptocurrency exchanges and cash-out services.79

Cryptocurrency is used by Islamic State terrorists in regions where local conditions permit and where other pressures necessitate alternative measures. Local groups are more inclined to use cryptocurrency for international transfers if there is already an established cryptocurrency market in their operating country, a developed cryptocurrency sector in the destination country, and a compelling reason to avoid conventional financial systems. This adaptation and adoption of financial technology is well beyond the proof-of-concept stage and has entered a mature period where the Islamic State increasingly uses stable and less expensive (in terms of transaction fees) cryptocurrencies (such as U.S. dollar-pegged Tether) and some privacy coins,80 demonstrating enhanced financial tradecraft.

Countering the Networked Islamic State Problem

The future of the Islamic State’s financial infrastructure is networked, resilient, and adaptive. The network has achieved this by focusing local groups on finance and governance and combining new and old methods of moving funds. The network also has redundancies: Revenue-sharing between groups and provinces allows the redistribution of funds to weaker groups or those that have suffered disruption, either because of between-group competition in their areas of operations or because of state or international CTF (countering the financing of terrorism) activities. As a result, countering the financing of the network will be an international coordination challenge, exacerbated by the great power division in some of the institutions for combating terrorism like the U.N. Security Council (and associated monitoring teams), and the expulsion of Russia from the Financial Action Task Force.

There are currently insufficient kinetic counterterrorism efforts being applied to disrupt the territorial control of Islamic State sub-groups. Without a sustained and effective kinetic counterterrorism approach, the group’s revenue-generating taxation and extortion activities will remain operational. Further, cash storage sites used by these groups will continue to amass funds, helping to sustain groups (and the broader network) over the long term. The current lack of investigative capacity to disrupt terrorist financing activities (through investigations and arrests) of terrorist financiers also remains a challenge for CTF and means that many Islamic State financiers and financial facilitators can operate with impunity. This is true for both the areas where Islamic State sub-groups operate directly, but also for their support areas outside direct conflict zones.

In many places where the Islamic State operates, regulations to prevent terrorist financing in the financial sector are lacking, as is cryptocurrency regulation. This has led to a lack of monitoring and reporting, which is vital for detecting and disrupting terrorist networks. This lack of financial surveillance means that significant gaps exist in the understanding of Islamic State networks. It also means that key facilitators and financial leaders operate freely, and many retain access to the global financial system, allowing them to move money for both organizational purposes, as well as terrorist attacks and other operational activity.81

Unfortunately, the prospect for success in countering the Islamic State’s finance network is poor. Many states where the group operates are struggling to maintain basic order and the rule of law and are primarily focused on preventing terrorist attacks. (Many states fail to understand fully the connection between finance and attacks and fail to resource and prioritize financial investigations. But terrorists with less money are less deadly.) Further, states are stretched thin, combating a growing number of security threats. The international strength of the Islamic State (and its network) is further bolstered by its ability to maintain safe havens and evade financial controls and by global connectivity.82 Because of the lack of international counterterrorism pressure against the Islamic State, the Islamic State will likely maintain its financial strength. The only question that remains is whether the Islamic State will use this strength to focus on governance and state-building in the long term or turn its attention to external attacks. Without serious counterterrorism pressure against the Islamic State’s finance network and sub-groups, the choice will be its own to make.

Substantive Notes

[a] Identity-based support networks are individuals and small groups who identify with the cause. One of the tangible ways they express this support is by providing small amounts of money directly to terrorist groups or to individuals planning terrorist activity.

[b] Hawala is a system used to move money domestically and internationally and is particularly popular in non-Western countries and in countries with under-developed formal banking sectors. The hawala system pre-dates modern banking and eschews current bookkeeping practices. Hawala transactions involve the movement of money between two (or more) locations without the physical transfer of funds, except for the settlement of accounts between hawaladars, or hawala operators. Hawala is often described as trust-based systems; in practice, these are businesses with established and verified relationships, often based on extended family networks.

Citations

[1] David Kenner, “All ISIS Has Left Is Money. Lots of It,” Atlantic, March 24, 2019.

[2] “Thirty-Third Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team Submitted Pursuant to Resolution 2610 (2021) Concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and Associated Individuals and Entities,” United Nations Security Council, January 23, 2024.

[3] Aaron Y. Zelin, “A Globally Integrated Islamic State,” War on the Rocks, July 15, 2024.

[4] Tore Refslund Hamming, “The General Directorate of Provinces: Managing the Islamic State’s Global Network,” CTC Sentinel 16:7 (2023).

[5] Kenner.

[6] Mara Redlich Revkin, “What Explains Taxation by Resource-Rich Rebels? Evidence from the Islamic State in Syria,” Journal of Politics 82:2 (2020): pp. 757-764.

[7] Jessica Davis, Illicit Money: Financing Terrorism in the 21st Century (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2021).

[8] “‘Millions’ in Isis Cash Destroyed in Airstrike on Storage Site in Mosul,” Guardian, January 12, 2016; Jessica Davis, “ISIL’s Al-Rawi Network,” Insight Monitor, April 27, 2023.

[9] Davis, “ISIL’s Al-Rawi Network.”

[10] Zelin.

[11] Kenner.

[12] Ibid.

[13] “Treasury Designates Key Nodes of ISIS’s Financial Network Stretching Across the Middle East, Europe, and East Africa,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, April 15, 2019.

[14] “Fact Sheet: Countering ISIS Financing,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, February 27, 2024.

[15] Hamming.

[16] Tricia Bacon, Austin C. Doctor, and Jason Warner, “A Global Strategy to Address the Islamic State in Africa,” ICCT Perspective, June 29, 2022; Uday Bakhshi and Adam Rousselle, “The History and Evolution of the Islamic State in Southeast Asia,” Hudson Institute Reports, February 28, 2024.

[17] Jacob Zenn, “ISIS in Africa: The Caliphate’s Next Frontier,” Terrain Analysis, Newlines Institute for Strategy and Policy, May 26, 2020.

[18] Author interview, Islamic State network expert 1, October 2023.

[19] “Fact Sheet: Countering ISIS Financing.”

[20] “Eighteenth Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team Submitted Pursuant to Resolution 2253 (2015) Concerning Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and Associated Individuals and Entities,” United Nations Security Council, July 19, 2016, paragraph 26.

[21] “Fact Sheet: Countering ISIS Financing.”

[22] Ibid.

[23] Katharine Houreld, “As ISIS Affiliate Expands in Central Africa, Escapees Recount Horrors,” Washington Post, August 11, 2023; Alexis Arieff, “The Allied Democratic Forces, an Islamic State Affiliate in the Democratic Republic of Congo,” Congressional Research Service, September 1, 2022.

[24] Elena Martynova, “ISIL-Affiliated Allied Democratic Forces,” Insight Intelligence, April 6, 2023.

[25] “Winning Peace in Mozambique’s Embattled North,” Crisis Group Africa Briefing N°178, International Crisis Group, February 10, 2022.

[26] Author interview, Islamic State network expert 3, October 2023.

[27] “Thirty-Second Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team Submitted Pursuant to Resolution 2610 (2021) Concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and Associated Individuals and Entities,” United Nations Security Council, July 25, 2023, paragraph 86.

[28] Jessica Davis, “ISIL-KP Financing,” Substack newsletter, Insight Intelligence, August 8, 2023.

[29] Caleb Weiss, Ryan O’Farrell, Tara Candland, and Laren Poole, “Fatal Transaction: The Funding Behind the Islamic State’s Central Africa Province,” GW Program on Extremism & Bridgeway Foundation, June 2023.

[30] Colin P. Clarke, Kimberly Jackson, Patrick B. Johnston, Eric Robinson, and Howard J. Shatz, “Financial Futures of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant: Findings from a RAND Corporation Workshop,” RAND Corporation, March 29, 2017, p. 18.

[31] “Thirty-First Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team Submitted Pursuant to Resolution 2610 (2021) Concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and Associated Individuals and Entities,” United Nations Security Council, February 13, 2023, paragraph 33.

[32] “Thirty-Second Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team,” paragraph 81.

[33] Ibid., paragraph 81.

[34] “Thirty-First Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team,” paragraph 76.

[35] “Islamic State in Libya (IS-Libya),” Australian National Security, November 29, 2022; Elena Martynova, “The Financial Evolution of IS Libya,” Insight Intelligence, May 4, 2023.

[36] A version of this figure was previously published in Jessica Davis, “The State of Terrorist Financing, as Seen by the United Nations,” Insight Monitor, accessed July 18, 2024.

[37] Weiss, O’Farrell, Candland, and Poole.

[38] Ibid., p. 41.

[39] Davis, “ISIL’s Al-Rawi Network.”

[40] “Treasury Designates Key Nodes of ISIS’s Financial Network Stretching Across the Middle East, Europe, and East Africa.”

[41] “IntelBrief: Unraveling the Rawi Terrorist Financing Network,” Soufan Center, April 25, 2019.

[42] “Treasury Designates Key Nodes of ISIS’s Financial Network Stretching Across the Middle East, Europe, and East Africa.”

[43] Ibid.

[44] Davis, “ISIL’s Al-Rawi Network.”

[45] Weiss, O’Farrell, Candland, and Poole, p. 31.

[46] “Treasury Sanctions South Africa-Based ISIS Organizers and Financial Facilitators,” U.S. Department of The Treasury, March 1, 2011.

[47] “Fact Sheet: Countering ISIS Financing.”

[48] Weiss, O’Farrell, Candland, and Poole, p. 32.

[49] “Thirty-Second Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team,” paragraph 27.

[50] “Country Reports on Terrorism 2019: Sudan,” U.S. Department of State, accessed August 31, 2023.

[51] “German Authorities Arrest Man Suspected of Sending Cryptocurrency to ISKP,” TRM Insights, June 13, 2024.

[52] Davis, Illicit Money.

[53] Author interview, Islamic State regional expert 2, November 2023.

[54] Lucas Webber and Laith Alkhouri, “Tajik Islamic State Network Fundraises in Russia,” Eurasianet, June 13, 2022.

[55] Elena Martynova, “Terrorism in Moscow: The Money Behind the Crocus City Hall Attack,” Insight Monitor, June 27, 2024.

[56] Katharine Houreld, “Killing of Top ISIS Militant Casts Spotlight on Group’s Broad Reach in Africa,” Washington Post, February 3, 2023.

[57] Scott Morgan, “A New Security Phase for the Islamic State Insurgency in Northern Mozambique,” Militant Wire, November 28, 2022.

[58] Author interview, Islamic State regional expert 2, September 2023.

[59] Hamming, p. 24.

[60] Ibid.

[61] “Treasury Designates Al-Qaida, Al-Nusrah Front, AQAP, And Isil Fundraisers And Facilitators,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, August 28, 2023.

[62] “Fact Sheet: Countering ISIS Financing.”

[63] “Thirty-Second Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team,” paragraph 25.

[64] Mohamed Djirdeh Houssein, “11. Somalia: The Experience of Hawala Receiving Countries,” in Regulatory Frameworks for Hawala and Other Remittance Systems (International Monetary Fund), accessed July 23, 2024.

[65] Jessica Davis, “The UN Says up to 20% of Terrorist Financing Cases Involve Crypto!” Insight Monitor, January 9, 2024.

[66] Author interview, Islamic State regional expert 3, November 2023.

[67] Nodirbek Soliev, “The Digital Terror Financing of Central Asian Jihadis,” CTC Sentinel 4:16 (2023).

[68] Weiss, O’Farrell, Candland, and Poole, p. 34.

[69] “Treasury Designates Senior ISIS-Somalia Financier,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, August 10, 2023.

[70] “OFAC Sanctions Crypto Address Associated With ISIS,” TRM Insights, July 31, 2023.

[71] “Treasury Designates Leaders and Financial Facilitators of ISIS and Al-Qa’ida Cells in Maldives,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 31, 2023.

[72] “Fact Sheet: Countering ISIS Financing.”

[73] Jessica Davis, “Terrorist Financing in the Maldives: Crypto Front and Centre,” Insight Monitor, January 9, 2024.

[74] “Thirty-First Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team,” paragraph 82.

[75] “TRM Finds Mounting Evidence of Crypto Use by ISIS and Its Supporters in Asia,” TRM Insights, July 21, 2023.

[76] “Thirtieth Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team Submitted Pursuant to Resolution 2610 (2021) Concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and Associated Individuals and Entities,” United Nations Security Council, July 15, 2022, paragraph 85.

[77] “Fact Sheet: Countering ISIS Financing.”

[78] “The 2023 Global Crypto Adoption Index,” Chainalysis, September 12, 2023.

[79] Jessica Davis, “Cryptocurrency Meets Hawala,” Insight Monitor, February 10, 2022.

[80] “Terrorist Financing: Six Crypto-Related Trends to Watch in 2023,” TRM Insights, February 16, 2023.

[81] Jessica Davis, “Understanding the Effects and Impacts of Counter-Terrorist Financing Policy and Practice,” Terrorism and Political Violence 36:1 (2024).

[82] “Fact Sheet: Countering ISIS Financing.”