Coastal West African countries can strengthen resiliency to the threat of violent extremism by enhancing a multilayered response addressing local, national, and regional priorities.

Highlights

Extremist violence in the Sahel is spilling over into coastal West African countries.

Governments in coastal West African countries play the leading role in responding to this threat by proactively strengthening ties with local communities in vulnerable regions.

Regional security cooperation can bolster national defenses through intelligence sharing, coordinating border patrols, and training focused on community protection.

Forging a multitiered strategy—linking support to communities with regional and international bodies—would help contextualize local responses while sustaining regional cooperation to address the complex threat posed by violent extremist groups.

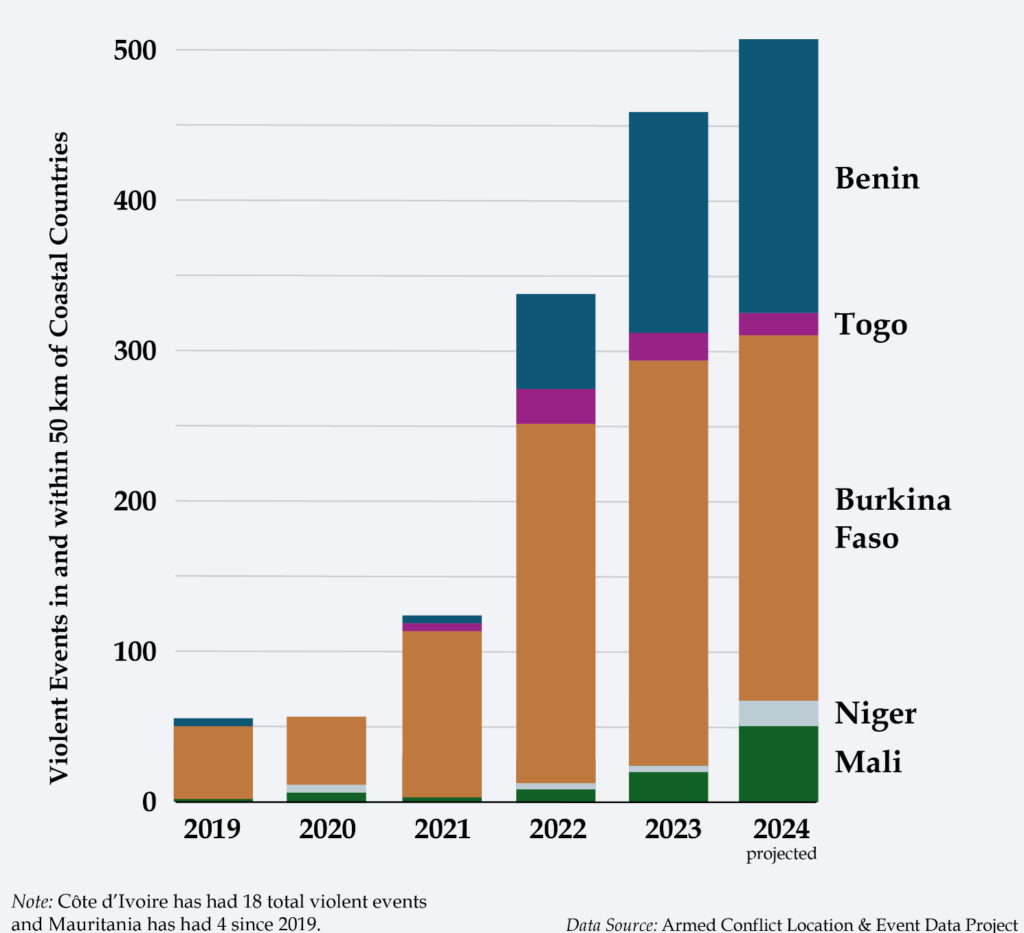

A spike in militant Islamist group attacks in coastal West Africa is validating long-held fears that unmitigated extremist violence in the Sahel will spill over into its neighbors. Benin has been hardest hit with a doubling in the number of recorded fatalities (to 173 deaths) in the past year. Togo has similarly faced a rise in militant Islamist violence including 69 fatalities over the same time period. The border areas of Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Senegal, and Mauritania are all facing greater strains from various militant groups attempting to enflame tensions within and between communities as a means of gaining access and influence. The annual number of violent events linked to militant Islamist groups in and within 50 km of the borders of the Sahel’s coastal West African neighbors has increased by more than 250 percent over the past 2 years, surpassing 450 incidents.

Initially centered in Mali, militant Islamist group activity has shifted progressively westward and southward throughout Burkina Faso, crossing the borders of neighboring coastal countries. The Sahel has seen a doubling in the number of violent extremist events since 2021 and a near tripling in fatalities linked to these events over the same period.1 Militant Islamist groups have displaced millions, shuttered thousands of schools, and left 12.7 million people food insecure in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger.

Violence has rapidly accelerated in the wake of military coups in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, destabilizing the Sahelian subregion.Violence has rapidly accelerated in the wake of military coups in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, destabilizing the Sahelian subregion.2 Meanwhile, regional security cooperation has been strained by the military juntas’ dissolution of regional security initiatives such as the G5 Sahel and the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). Regional cooperation has been further aggravated by the juntas’ stated intentions to withdraw from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and creating their own tripartite security framework, known as the Alliance des États du Sahel.

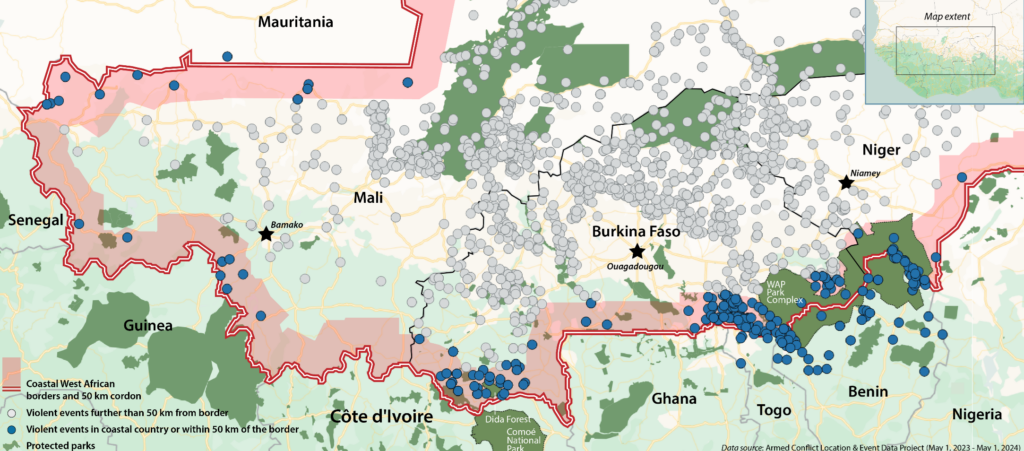

Insecurity in coastal West Africa has been particularly pronounced in borderlands and jointly protected areas like the massive W-Arly-Pendjari (WAP) Complex of parks, which includes territory from Benin, Burkina Faso, and Niger and is near Togo, Ghana, and Nigeria.3 The parks’ transboundary location amplifies the complexity this security challenge poses for regional cooperation.

Violent extremism and other cross-border threats such as smuggling, organized crime, and poaching can compound internal fragilities such as limited government service delivery, anti-government disinformation, and intercommunal tensions—potentially triggering the destabilization of local communities and governments in the region.

The decline in cross-border cooperation and supporting intelligence capabilities with the juntas in Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mali have sparked interest among the coastal countries to strengthen bilateral and collective means to address the growing threat on their side of the border. Enhancing the cohesion, coordination, and scale of these coastal West African efforts to mitigate the threats may avoid a much larger and more costly regional impact.

Militant Islamist Groups Threatening Coastal West Africa

The threat of militant Islamist groups to coastal West Africa is not monolithic. Violent extremist groups in the Sahel are often characterized as belonging to Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wal Muslimeen (JNIM), a loose coalition of different groups claiming al Qaeda affiliation, or the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS). Yet, the origins and evolution of the militant groups comprising JNIM and ISGS is more complex.4 Analyzing the distinct dynamics of militant Islamist groups by zone and specific actors offers more fruitful consideration when developing strategies and responses to the distinct threats each group poses.

The rapid westward and southward expansion of militant Islamist violence in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger in recent years has dramatically increased the number of violent events pushing up to and spilling over the borders of coastal West African countries from Mauritania to Nigeria. While most attention has been focused on Benin and Togo, there have been two dozen violent extremist incidents in Mali within 50 km of the borders of Mauritania, Senegal, and Guinea—in regions where, until recently, there was little to no activity. Aside from this threat, two primary theatres of violent extremist activity have emerged in southern Burkina Faso and Niger that threaten their coastal neighbors.

Mali—Côte d’Ivoire—Burkina Faso Tri-Border Zone

The tri-border zone, where Mali, Côte d’Ivoire, and Burkina Faso’s boundaries meet, represents a strategic artery for the subregion. Roughly 25 percent of Mali’s imports travel from Abidjan to Bamako. Similarly, 30-35 percent of Burkina Faso’s imports enter through the Abidjan-Bobo Dioulasso corridor. More than half of Burkina Faso’s exports, including its valuable cotton sector, rely on Abidjan’s port.

There is also significant artisanal gold mining throughout this zone, which attracts migrant workers from the three countries as well as Guinea. These artisanal sites featured prominently in the revenues generated to support northern armed groups in the Ivorian conflict during the 2000s. The confluence of trade flows, artisanal gold mining and smuggling networks, and arms trafficking all present attractive targets of influence for militant Islamist groups in the subregion.

In Burkina Faso’s southwestern Cascades Region, the Macina Liberation Front (FLM) led by Amadou Koufa has been increasingly active since 2018. Locally, the militant group is believed to be led by a commander using the nom de guerre “Hamza”5 and has tapped into smuggling and trafficking networks as well as artisanal mining sites. Recruiting from marginalized populations, intermixing with criminal actors, and establishing ongoing revenue streams have made the violent extremists more self-reliant. They have subsequently intimidated communities, forced recruitment, employed extortion euphemistically presented as a religious tax or “zakat,” and at times attempted to enforce oppressive laws related to gender roles, dress, and religious practice. They have increasingly targeted security forces and government representatives.

Having established themselves in Burkina Faso near the Dida Forest bordering northern Côte d’Ivoire, the group began staging attacks across the border on Ivorian security forces in 2020, including an attack on an army-gendarmerie post in Kafolo. The Ivorian government responded by rapidly increasing its security presence and socioeconomic investment in the region.

As the militants have expanded southwestward, they have become an increasing threat to Burkinabe communities along the borders with Côte d’Ivoire and Mali, establishing encampments in protected forests there. Displaced residents have sought refuge in Côte d’Ivoire. While FLM has not yet targeted communities in Ghana, the Dida Forest is only 100 miles (150 km) from the Ghanaian border. On the Ivorian side of the border is the Comoé National Park, an expansive hinterland of mostly wilderness. Should the militants operating in Burkina Faso establish themselves in the park, it may become increasingly difficult to root them out of the area.

The W-Arly-Pendjari Park Complex

A second predominant theatre concerns the 26,361-km2 WAP Complex of national parks. Protection of this UNESCO World Heritage transboundary biosphere reserve entails coordination among multiple governments across a range of issues including management of the environment, community relations, and more recently security. The parklands have become a haven for militant Islamist groups since 2018, when fighters from the JNIM-aligned groups—FLM, Katiba Serma, and Ansaroul Islam—established hideouts there. ISGS has also used the park on the Nigerien side. Over time, militants have developed local connections recruiting from vulnerable youth and building ties with smuggling networks, which thrive using the national parks around illicit trade in fuel, cigarettes, counterfeit goods and medicines, arms trafficking, and gold.

Major commercial trade and economic corridors pass near to the WAP Park Complex. They include the Ouagadougou-Lomé, Niamey-Lomé, Niamey-Cotonou, Ouagadougou-Accra, and Niamey-Ouagadougou corridors. Roughly two-thirds of Burkina Faso’s imports enter the country through these corridors. Meanwhile, the Niamey-Cotonou corridor is Niger’s primary import-export route, handling on average more than 50 percent of Niger’s trade. An additional 20 percent of Niger’s imports rely on these corridors passing through Burkina Faso. All of these corridors have come under increasing threat from militant Islamist groups operating in the border areas of the WAP Park Complex.

Little is known about the leadership structures of the violent extremist groups operating in the WAP parklands. Residents of local communities that have dealt with the militant Islamists link them to FLM’s Amadou Koufa and Ansaroul Islam’s Jafar Dicko, but neither of these leaders are believed to travel to the park itself. Some security officials refer to the groups as Katiba Hanifa, a reference to a supposed Nigerien leader Abu Hanifa. Other possible local commanders include Abu Issa in Burkina Faso and Cheick Albani in northern Benin.6 The lack of clarity around the groups and their composition highlights the limited intelligence available on their operations.

From their camps within the WAP Park, the militant Islamists target artisanal gold mining sites around the reserve while also trading with, and at times extorting, livestock herders who move through and around the parklands. The extremists have attempted to present themselves as an alternative governing authority, at times imposing strict adherence to their interpretation of Sharia law. Communities living near the reserve, particularly in Burkina Faso but also increasingly in Benin, have been attacked by the militant Islamist groups. More recently, Togo has seen increased incursions from the groups that are using the western range of the reserve lands to expand across southeastern Burkina Faso.

The WAP Park Complex is an instructive example of how uncontrolled border regions provide safe havens for militant Islamist groups operating in this region. They can move on either side of the border and take refuge in the parklands to evade security forces. The reduced cross-border cooperation and coordination following the coups in Burkina Faso and Niger have benefitted violent extremists seeking cover in this sprawling reserve.

Pastoralists, farmers, and smugglers using the protected areas have been involved in confrontations with conservation and security officials, at times leading to evictions, arrests, abuses, slaughter of livestock, and destruction of fields. Violent extremists have stoked the grievances these enforcement actions have caused to mobilize recruitment and support, highlighting the security challenges of combatting militant groups in a high-value economic corridor while protecting communities and a country’s natural resources.

National Responses to the Expanding Insecurity

Violent extremist groups in the Sahel have long exploited intercommunal tensions to stir up social discord, weaken trust of government, and recruit supporters. Accordingly, a top priority for local authorities and central governments of coastal West African countries is improving access to basic social services, developing income-generating activities, and enhancing trust between the security forces and the population in border regions.

The Ivorian government launched its Programme spécial du Nord in 2022 that combines an increased security presence in its northern border regions with investments in infrastructure and social programs targeting unemployed and undereducated youth.7 The program has been lauded as a successful model and may have contributed to the reduction in militant Islamist activity observed in Côte d’Ivoire since 2021. Previous joint force cross-border operations between Ivorian and Burkinabe forces (2020–2021) also contributed to enhanced security, communication, and coordination across the border. However, since the 2022 coups in Burkina Faso, relations have frayed and joint operations have largely ceased, increasing vulnerability.

In Togo, the government initiated an ambitious $26.6-million multisectoral program in 2022, the Programme d’urgence pour les Savanes, in its northernmost region.8 The West Africa Development Bank is supporting this program with an additional $50 million targeting the improvement of infrastructure, social service delivery, and economic resilience in the region. A state of emergency in place since June 2022 has resulted in greater troop deployments in northern Togo. This has, at times, resulted in accusations of heavy-handed tactics by the security forces—an outcome counter-productive to the objective of building rapport with vulnerable communities.

In Ghana, a comprehensive decentralization program, including the redrawing of administrative jurisdictions in the northern regions, has gone hand in hand with investments in border security and intelligence gathering. The government has also sent soldiers and law enforcement to boost security in communities where intercommunal tensions are high and there is a known presence of violent extremist groups.9 The professional conduct of the Ghanaian security forces has helped reduce violence and tension in northern Ghanaian communities, demonstrating that these efforts are a critical element of an effective conflict prevention strategy.

Benin has been the hardest hit of the coastal countries by violent extremist insecurity. The creation of the Benin Agency for the Management of Border Areas has aimed to combine security, prevention, and development in Benin’s border communities. However, community policing initiatives designed to build trust with vulnerable populations have been limited and slow to deal with the escalating threat. As a result, Benin has mobilized 3,000 soldiers as part of its Operation Mirador to patrol border areas to counter increasing militant Islamist attacks on communities, security forces, and park rangers.

The sudden presence of the military forces has, however, exacerbated tensions with local communities. These sometimes heavy-handed operations have inadvertently deepened grievances with the government.10

Operation Mirador is augmented with an additional 4,000 soldiers who are deployed on a rotating and seasonal basis. The military has also recruited some 1,000 local forces to enhance their intelligence capabilities on the ground in the north. Given the significant WAP Park territory bordering Burkina Faso and Niger, the security forces work closely with the South African-based nonprofit conservation organization African Parks, which manages the Beninese side of the Pendjari Park and Park W reserves under a public-private agreement.

Security forces now must strategize ways to dismantle the complex illicit networks and root out Islamist militants while protecting and building trust with local communities.Benin had worked closely with the Nigerien security forces, signing a military cooperation agreement in July 2022 with the aim of improving cross-border security. Following Niger’s July 2023 coup d’état, however, the Nigerien junta abruptly broke the cooperation agreement. Similarly, discussions over the feasibility of creating a unified management and security structure for the park complex, with African Parks taking over management of the Nigerien and Burkinabe sides of the WAP reserve, were also put on hold.

Adding to the complexity, militant Islamist groups have attempted to exploit local resentments along the border regions, including fears over the loss of livelihoods dependent on illicit networks.11 Security forces now must strategize ways to dismantle the complex illicit networks and root out Islamist militants while protecting and building trust with local communities.

Regional Security Cooperation in Coastal West Africa

Beyond national considerations, the cross-border implications of countering violent extremism in these border zones highlight the importance of regional security coordination. ECOWAS has been the preeminent regional cooperation framework in West Africa due to the political will of its members, strong legal framework, and long-term experience in peace and security. ECOWAS has conducted numerous peacekeeping operations and developed the ECOWAS Standby Force (ESF) as part of the African Union Peace and Security Architecture. The ESF replaced the ECOWAS Ceasefire Monitoring Group (ECOMOG) at the start of the 2000s. However, the growing threat of violent extremism in West Africa has revealed major challenges to mobilizing its forces in recent years.

President Bola Ahmed Tinubu of Nigeria has called for the reactivation of the ESF. Yet, there is still a significant gap between the official discourse on its readiness and the reality of its adequacy. The rise of insecurity in the Sahel and the spillover of violence into coastal countries, meanwhile, has been a trigger for the coastal governments to develop selective ad hoc initiatives to respond to the evolving threat.

The Accra Initiative (2017–present)

Following a high-profile terrorist attack in Grand-Bassam, Côte d’Ivoire, and the expansion of militant Islamist violence from Mali into Burkina Faso, the Burkinabe government and its four coastal neighbors—Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, and Togo—established the Accra Initiative in 2017 to combat the spread of violent extremism, prevent terrorist attacks, and address transnational organized crime within their territories. Mali and Niger joined in 2020, and Nigeria has maintained observer status since April 2022.

Given its membership, the Accra Initiative represents the most logical body to coordinate greater regional security cooperation in coastal West Africa. The Accra Initiative’s context-specific design aims to foster greater coordination by bringing together a coalition of the willing as a form of cooperation broker. The initiative serves as an intermediary between a set of countries that are geographically close, share regional security objectives, and need to construct collective mobilization.

Together the members have prioritized three main areas of operational cooperation. First, they focus on intelligence gathering, collation, and sharing. This has entailed regular exchanges between security and intelligence agencies through a non-formalized framework of focal points. These engagements have contributed to building rapport across partner governments and their security personnel, fostering stronger cooperation to prevent violent extremism.

Cross-border joint security operations are the second and most visible of the Accra Initiative’s activities. Armed forces, operating largely within their own territories, under their own tactical commands, and with their own funding, have conducted periodic joint operations since 2018. Though they have been relatively short in duration with limited geographic scope, these operations have led to the arrest of suspected militants.

Better coordination strategies for confronting the militant Islamist groups operating in border zones, particularly around the WAP Park Complex territory and southwestern Burkina Faso, is an ongoing gap in the cross-border efforts. The already existing communications between the Accra Initiative focal points might easily be developed into a more formalized exchange center. Such a center could then facilitate strategic planning across the region to foster missing synergies in both the security response and livelihood initiatives that are being led by national governments. In this way the Accra Initiative can facilitate lessons sharing among its members.

The third pillar of the Accra Initiative is a training component. While the least developed feature of the Accra Initiative’s activities, many Accra Initiative members already have the infrastructure in place to organize counterterrorism and countering violent extremism training for their uniformed and civilian personnel. What is needed is the establishment of curricula and pre-deployment requirements for professional advancement.

Renewed attention to the importance of building trust with communities and upholding high standards of professionalism is also needed.Renewed attention to the importance of building trust with communities and upholding high standards of professionalism is also needed. Training on professional engagements with communities is crucial for inculcating soldiers with attitudes and behaviors of service. Successfully countering violent extremism and stabilization efforts depend highly on restoring, repairing, and maintaining good relations between the government and local communities.

Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF, 2015–present)

The MNJTF has a mandate to safeguard security in the areas threatened by the Boko Haram and Islamic State in West Africa (ISWA) by protecting civilians from violent attacks, implementing stabilization programs for Lake Chad Basin communities, and facilitating humanitarian operations and the delivery of assistance to affected populations. The MNJTF consists of approximately 10,000 troops from Nigeria, Chad, Cameroon, Niger, and Benin.

The MNJTF’s mandate involves a two-phase process. First, it conducts kinetic action against Boko Haram and its offshoots including counterterrorism operations, clearance campaigns, patrols, abductee search and rescue operations, and messaging campaigns to encourage defections. Second, the MNJTF provides a coordination platform to address drivers of violent extremism in the region through its Regional Strategy for the Stabilization, Recovery and Resilience (RS-SRR) of the Lake Chad Region. The RS-SRR lays out nine pillars of intervention with five focused on addressing underlying causes of violent extremism, including citizen-centered governance, socioeconomic recovery and environmental sustainability, expanding educational opportunities, peacebuilding, and empowering women and youth.12 Each of these pillars has strategic objectives, which serve as a framework for the Regional Strategy.

Adapting stabilization programs to community needs in turn helps facilitate local ownership and buy-in.In the first phase of the mandate, MNJTF forces collaborate with national commands to coordinate their efforts. MNJTF commanders maintain regular communication with field commanders on the borders to relay national forces’ operations. In this way, the MNJTF forces augment national efforts and serve as important connective tissue for communications between the different Lake Chad Basin national armed forces. These characteristics have proved essential in the MNJTF’s operations to surge military capacity and clear areas of Boko Haram and ISWA activities. The MNJTF also works to coordinate its efforts with local security actors, such as the Civilian Joint Task Force in northeastern Nigeria, often through national-level forces.

In addition to its military component, the MNJTF is well aligned with civilian-led efforts to manage conflict. The MNJTF, as part of the RS-SRR, has worked primarily through its Civil-Military Cooperation Cell to coordinate local security efforts to extend humanitarian access, the safe cross-border return of refugees, and the secure opening of borders in support of human mobility and cross-border trade. The Lake Chad Basin Commission, a regional body charged with managing Lake Chad’s resources, has served as a facilitating platform connecting relevant local governors across the region alongside civil society organizations from local communities to provide input into MNJTF activities.13 This has enabled civilian ministries and local administrators to be more engaged in the MNJTF’s stabilization efforts, which has in turn reinforced objectives and redirected resources to fill other community needs.

Working in an integrated fashion down to the local level has helped the MNJTF build broader trust among communities. It has done this through strategic planning alongside civilian stakeholders and through the comprehensive RS-SSR. Faced with complex insurgencies that take advantage of local grievances and are adept at exploiting heavy-handed state responses, this type of layered multitiered response has proven to be a key ingredient to the MNJTF’s successes.

The adaptability built into the RS-SSR’s design also allows for the MNJTF to work alongside partners at all levels to meet communities’ needs. Adapting stabilization programs to community needs in turn helps facilitate local ownership and buy-in. These elements are critical to countering violent extremism in contexts where multiple national governments must grapple with the best response for varying communities.

Enhancing a Regional Response to the Growing Crisis

Violence from militant Islamist groups in the Sahel is rapidly expanding across West Africa, affecting communities in the border regions of multiple coastal West African countries. The shared security threats, geographic proximity, and vested interests of Benin, Togo, Ghana, and Côte d’Ivoire—potentially including Guinea, Senegal, and Mauritania—with their Sahelian neighbors underscore the need for enhanced regional coordination. Through the Accra Initiative, these coastal countries have improved intelligence sharing, security cooperation, and resource sharing—though much more can be done. Lessons from the MNJTF’s multitiered stabilization strategy in the Lake Chad Basin as well as lessons from Accra Initiative member states’ national strategies illuminate priority areas for investment and actions to implement.

Improve the conduct of security forces to build rapport with communities. Militant Islamist groups have been able to exploit porous borders. Stepping up deployments of army, police, and customs forces in the border regions of coastal West African countries, therefore, is a necessary but insufficient requirement. A foundational lesson for stabilization efforts is for all deployed security forces to be respectful of local citizens and their property. Avoiding heavy-handedness and building the trust and confidence of local populations is a key component of successful counterinsurgency.14

Institutions with the capacity to enhance the professionalism and conduct of security forces . . . might be vehicles from which the Accra Initiative’s training repertoire can be quickly scaled up.Consistently applying citizen-centric practices across the coastal West African security forces will require increased efforts to train national forces on civilian harm mitigation and community relations. Benin has already enhanced its training regimen by mandating that all career soldiers who attend professional military education institutions deploy to the field for an Immersion des stagiaires that lasts several months for each cohort. Similar programs might be developed to enhance community trust and civilian harm mitigation.

Institutions with the capacity to enhance the professionalism and conduct of security forces are already present in the region. Côte d’Ivoire, for instance, hosts the International Academy for the Fight Against Terrorism, and Ghana hosts the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre. These and other professional military education institutions might be vehicles from which the Accra Initiative’s training repertoire can be quickly scaled up.

Accelerate development efforts in vulnerable areas. Investments in development initiatives in border areas such as those undertaken in Côte d’Ivoire have proven to be an effective stabilization strategy. Replicating and ramping up such integrated service provision for all coastal West African countries is a priority for building trust with local communities and mitigating recruitment by violent extremist groups. Investment in social programs underscores that stabilization will require more than military-based solutions.

Investment in social programs underscores that stabilization will require more than military-based solutions.Countries such as Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana can play a valuable role in providing training and facilitating the sharing of best practices from across the subregion. This learning process can be expedited by arranging development exchanges among the coastal countries and mobilizing funding for socioeconomic projects in the border areas.

Development initiatives in the border regions may also create openings for bilateral cooperation with the junta-led regimes in the Sahel. Ministries responsible for development issues in the Sahelian countries are more likely to be headed by civilians—often seasoned professionals in the fields of environment, infrastructure, or sanitation—presenting opportunities to pursue cross-border cooperation initiatives that work toward stability.

Establish a regional strategy to mitigate risks from the WAP Park Complex. Given the expanded militant Islamist activity in the WAP parks, coordination among Benin, Togo, Ghana, and Nigeria regarding their governing policies for borderlands and protected spaces is crucial to honing an effective stabilization strategy. Drawing on lessons from the MNJTF’s engagements with the Lake Chad Basin Commission and its linkages to local communities within the region may provide fruitful inspiration for developing a multitiered approach to protecting the communities around the WAP Park Complex and its protected ecosystems.

Like the Lake Chad Basin, areas of the WAP parks are under the effective control of violent extremists. This will require a two-phase approach that employs coordinated kinetic operations to eliminate the militant Islamist groups from the border areas and parklands, combined with regional- and international-supported efforts to help preserve the fragile environment in and around the park reserves on which local livelihoods rely. This will require community-tailored initiatives that balance varied interests and objectives.

Joint border management responsibilities that balance sustainable pastoralism, farming, and wilderness protection will need to be elaborated. The success of such initiatives depends heavily on raising awareness ahead of implementation and the broad inclusion of local civil society, community religious and traditional leaders, youth, and women for their input on proposed responses.15

Conservation management efforts that benefit local communities and counter illicit networks and violent extremism within a multitiered and multistakeholder strategy will be a key ingredient to responding to violent extremism.Public-private partnerships like that struck between the Government of Benin and African Parks may be instructive. The conservation organization has made progress working with communities to address contentious issues between communities while upholding the conservation of the parklands. Further conservation management efforts that benefit local communities and counter illicit networks and violent extremism within a multitiered and multistakeholder strategy will be a key ingredient to responding to violent extremism in the WAP region.

Should cooperation be improved with Mali and Burkina Faso, a similar strategy for the border areas around Comoé National Park and Dida Forest in the Mali—Côte d’Ivoire—Burkina Faso tri-border area could use a WAP strategy as a model.

Synchronize joint assessments of conflict risks. Coastal West African countries can enhance and streamline intelligence sharing across the members of the Accra Initiative by maintaining regular reporting and communications channels among security actors of movements of militant Islamist groups. This lateral communication can partly compensate for the limited intelligence sharing from the Sahelian juntas. It can also reveal the variation in motives and tactics of the violent extremist actors that are not monolithic but are a collection of groups, each with different command structures. In some cases, they operate more on criminal than ideological grounds, extracting natural resources, tapping illicit networks, and extorting local communities especially along key cross-border economic corridors.

These threat assessments could be paired with those of the ECOWAS Early Warning Response Network. Together the joint assessments would support an integrative stabilization strategy. ECOWAS could then also systematically use its Country Risk and Vulnerability Assessment to start a joint analysis process and regularly update it with all its members.

Adopt a multitiered stabilization strategy. Given the decentralized nature of the violent extremist threat and the experience of other regional security initiatives, coastal West African countries should forge a multitiered strategy and institutionalized approach toward stabilization.

The top priority and first layer of this strategy are local communities and government agencies in the border areas facing escalating extremist violence. Here leaders can develop specific actions and tactics that undercut opportunities for violent extremism to take root and boost community resilience. Working at this granular level helps reduce the chances that governments inadvertently exacerbate grievances.

A second layer is the national governments that are supporting these local efforts with integrated initiatives to both protect and support socioeconomic interests of these regions. The Accra Initiative represents a third layer of coordination, intelligence and resource sharing, joint operations in vulnerable border areas, and surge capacity in support of these national efforts.

The top priority and first layer of this strategy are local communities and government agencies in the border areas facing escalating extremist violence. As the principal regional coordination organization, ECOWAS represents a fourth tier of institutional support that can help facilitate policy and experience sharing from across the region to back up the coastal West African countries. ECOWAS may also provide financial or materiel assistance to the frontline countries, as needed. This includes facilitating donor support directly to the national governments engaged in stabilization efforts.

Should the security situation deteriorate further and warrant a full-fledged intervention, ECOWAS’s experience from other regional security initiatives would provide the basis for the deployment of the ECOWAS Standby Force. ECOWAS engagement can also facilitate policy coordination with a fifth layer of support, the African Union. In addition to the valuable political validation of these efforts, the coastal West African countries can tap established African Union guidelines on civilian protection and harm mitigation.

Collectively, this layered architecture provides the institutional dexterity to scale up and tap a wider breadth of resources and expertise than would be realized at any one level. This approach also recognizes the complexity of the violent extremist threat, which while operationalized locally, is unfolding across an expansive transboundary area drawing on regional networks of fighters, resources, and messaging.