Abstract: The Houthi rebels have been at war with the Yemeni government almost constantly since 2004. In the first six years, the Houthis fought an increasingly effective guerrilla war in their mountainous home provinces, but after 2010, they metamorphosed into the most powerful military entity in the country, capturing the three largest cities in Yemen. The Houthis quickly fielded advanced weapons they had never before controlled, including many of Iranian origin. The story of how they moved from small-arms ambushes to medium-range ballistic missiles in half a decade provides a case study of how an ambitious militant group can capture and use a state’s arsenals and benefit from Iran’s support.

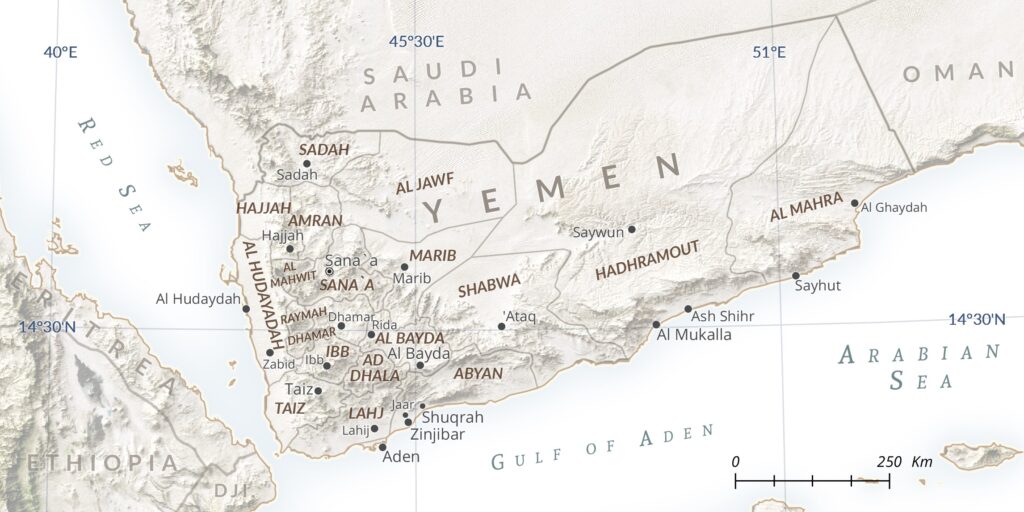

The Houthi movement1 refers not only to the Houthi family (a clan from the Marran Mountains within Sa’ada province) but also to a broader tribal and sectarian alliance operating mainly in northern Yemen. The Houthi clan are sadah (descendants of the prophet), and their modern patriarch was a respected religious scholar, Badr al-Din al-Huthi, an influential preacher until his death (by natural causes) in 2010.2 The Houthi family are adherents to the Zaydi branch of Islam, which venerates Ali as the legitimate heir to the prophet. Zaydis are doctrinally closest to Fiver Shi`a Muslims (as opposed to the more prevalent Twelver Shiism dominant in Iran, Iraq, and Lebanon).3 The Houthis rose to prominence in the aftermath of the fall of the Zaydi imamate (which ruled northern Yemen from 897 AD until 1962 AD) and at the time of the Islamic Revolution in Iran4 and the growth of Saudi-backed salafism in northern Yemen.5

By the 1980s, the Zaydi and sadah decline was answered with a new call for Zaydi revival, championed most actively by Badr al-Din al-Huthi and taken up by his prominent sons Hussein, Yahya, Mohammed, and Abdulmalik. The Zaydi revival was part social-revolutionary and part sectarian, calling for a reversal of government neglect of rural northern Yemen and limitation on the cultivation of anti-Zaydi salafism in the area.6 In the 1990s, Badr al-Din al-Huthi and his sons built a powerful, cross-cutting social network around the Zaydi revivalist movement that included intermarriage with tribal and sadah families, “Believing Youth” (Muntada al-Shahabal-Mu’min) summer camps and social programs, and a political party.7

The Houthi movement became more vocal in foreign and border issues from 2000 onward, ostracizing Yemen’s main allies—Saudi Arabia and the United States—and risking a clash with the government. By 2000, the movement was tapping into traditional xenophobic tendencies and fears of foreign domination in northern Yemen, in particular Saudi Arabia’s handling of border disputes.8 Always opposed to Israeli and Western security actions in the Arab world, the Houthi movement reacted furiously to the Palestinian Second Intifada and later to U.S. military interventions in Afghanistan, Yemen, and Iraq. In late 2000, the Houthi movement adopted its slogan, “the scream” (al-shi’ar): “Death to America, Death to Israel, Curse upon the Jews, Victory to Islam.”9 Explicit criticism of U.S.-Yemeni counterterrorism cooperation by the Houthis was a proximate cause for the commencement of hostilities by the Yemeni government in June 2004.

Guerrilla Wars: 2004-2010

In the first Houthi war, fought from June 22 to September 10, 2004, the rebels were unable to even defend cave complexes in their native Sa’ada province, with the result that their charismatic military leader Hussein Badr al-Din al-Huthi was captured and summarily executed on the battlefield in September 2004. By 2010, the same organization was able to fight the Yemeni government to a standstill in four provinces, seize and hold strategic towns, force entire surrounded brigades into surrender, and carve out tactical footholds inside Saudi Arabian border settlements.10 In the author’s assessment, this evolutionary transformation was arguably largely due to the counterproductive tactics of the Yemeni government, plus incremental improvements on the traditional soldierly qualities of northern Yemeni tribesmen.

In 2004, the Houthi movement’s armed cadres appear to have been small, numbering in the low hundreds—largely the family, friends, and students of Hussein Badr al-Din al-Huthi.11 From 2005 onward, the numbers of Houthi movement fighters swelled in response to government errors. The first was to progressively alienate Zaydis. After Hussein Badr al-Din al-Huthi’s death, the government posted images of his body on walls in Sa’ada, inadvertently chiming with Shi`a themes of martyrdom, elevating him to saint-like status, and agitating the Zaydi tradition of rising up against unjust rulers.12 Consolidation of co-religiosity was reinforced by the sacking of Zaydi shrine towns such as Dahyan and major population centers like Sufyan, and the use of sectarian themes (“Safavid Shiites”a) in government tribal mobilization.13

Northern tribes also flocked to the Houthis to gain revenge on common enemies and express tribal solidarity.14 Indiscriminate government use of heavy artillery and airstrikes resulted in a wave of tribal recruitment for the Houthis from 2006 onward, a reaction to the perception that the government was executing a “retaliatory policy against everyone” in the Houthi home provinces.15 The government also alienated tribes by deploying rival clans as auxiliary fighters within their native districts.16 The Houthi movement was well-placed to absorb and shape this influx of allies because of the aforementioned cross-cutting social relationships developed prior to 2004, notably the tens of thousands of young men sent through Believing Youth summer camps and social or educational programs under the stewardship of Badr al-Din al-Huthi’s sons.17 b War and mutual loss reinforced this “spirit of tribal solidarity” or “cohesive drive against others.”18

From the outset of fighting in 2004, the Houthi movement was able to field what Barak Salmoni, Bryce Loidolt, and Madeleine Wells called “kin-network-based fighting teams.”19 These teams have typically been no larger than platoon-sized (i.e., 20-30 strong).20 The most common ‘guerilla war’ (harb al-’isabat) tactics employed were ambushes with small-arms fire, sniping, and mines—the time-honored methods used by the same tribes (albeit then with Saudi support) in the 1960s war against Egyptian occupiers.21 As in the 1960s fighting, extraordinary ruthlessness and brutality was frequently employed by the Houthi movement to punish pro-government tribes, notably the execution of sheikhs,22 beheading of captives,23 display of bodies in public places,24 execution of children from offending families,25 and the ancient tradition of hostage-taking to ensure compliance.26

Over the course of the six wars, Houthi combat operations became progressively more effective and spread beyond Sa’ada province, requiring the Yemeni state to commit greater and greater effort to contain the threat, eventually also drawing the Saudi Arabian military into direct combat operations by 2009.27

In the second (March 19 – April 11, 2005) and third (November 30, 2005 – February 23, 2006) wars, the Houthis fought a hit-and-run war of raids, assassinations, ambushes, and terrorist-type operations in Sana’a.

During the fourth war (January 27 – June 17, 2007), the Houthis developed the defensive resilience to fortify and defend towns against armored attacks using mines, RPGs, and Molotov cocktails. They also mounted larger storming attacks on government complexes, sometimes in company-sized (i.e., 60-90 strong) units.28

In the fifth war (May 2 – July 17, 2008), the Houthi movement was attacking government logistics by controlling or destroying key bridges linking Sana’a to Sa’ada, probing the northern outskirts of Sana’a, and encircling and forcing the withdrawal of Yemeni units of up-to-brigade strength.29 During this war, the Houthi movement began producing its slick battle report video series, Basha’ ir al-Nasr (Prophecies of Victory).30

By the last of the six wars (August 11, 2009 – February 11, 2010), the Houthi movement was confident enough to force the surrender of an entire Yemeni brigade31 and mount a major assault at battalion strength (i.e., 240-360 strong) with armored vehicles on Sa’ada, seizing parts of the city from the government. The Houthis also initiated offensive raids into Saudi Arabia, undeterred by an unparalleled level of air surveillance and bombardment.32

State Capture and State Sponsorship: 2011-2014

The sixth Houthi war in 2009-2010 underlined the failing strength of the Yemeni government, which quickly succumbed to widespread Arab Spring protests from January 2011 onward, with President Ali Abdullah Saleh being ousted in November 2011. Setting aside previous rivalries between Houthi commanders,c the Houthi leadership took full advantage of this period of government collapse, extending a network of forces across northern Yemen to neuralgic locations that one Houthi field commander termed “hegemony points.”33 By March 2011, the Yemeni military had been expelled from Sa’ada and dissenting tribes were suppressed.34 In 2011, the Houthi movement adopted a formal name for the first time—Ansar Allah (Partisans of God)d—and developed a Beirut-based television station, Al-Masirah (The Journey), with Lebanese Hezbollah support.35

By the end of 2012, Ansar Allah controlled almost all of Sa’ada province and large parts of the adjacent governorates of Amran, al-Jawf, and Hajjah, “the largest part of Upper Yemen’s Zaydi heartland” as Marieke Brandt noted in 2013.36 These moves were informed not only by the Houthi clan’s historic skill as tribal mediators but also by some organized intelligence collection either undertaken by the movement or seized from government records. One deep expert on Yemen told the author, “the Houthis arrived in districts with files on tribal networks and local structures.”37 As Brandt noted in 2013:

“The Huthi rebellion works through carefully developed plans and brilliant moves on the chessboard. They rely on alliances, both secret and openly visible … The Huthi strategy is based on a precise knowledge of the local tribes and on widespread social presence in their areas; they set up a tight network of checkpoints and patrol in the hamlets in operations that local sources describe as Huthi operations to feel the tribe’s pulse.”38

Alongside opportunistic territorial expansion, Ansar Allah worked to capture the armaments of the state and to draw on direct support from Iran and Lebanese Hezbollah. In a first step toward state capture, as one of the anti-government protest factions, the Houthi movement coopted officials within the transitional governing structure, particularly the Ministry of Defense. The Houthi movement also worked with the ousted Ali Abdullah Saleh to position itself for the takeover of the capital, which eventually unfolded as a smoothly executed coup on September 21, 2014. In addition to the absorption of entire brigade sets of tanks, artillery, and anti-aircraft weapons, Ansar Allah also seems to have used its alliance with Saleh to coopt Yemen’s strategic missilee and coastal defense forces, as well as national intelligence agencies.f As the Houthi movement seized power in Sana’a, it inherited as many as six operational 9M117M launchers and 33 R-17E Elbrus (NATO name SS-1C Scud-B) short-range ballistic missiles, a system with a range of 310 miles.39

In addition to coopting Yemen’s war machine, Ansar Allah appear to have taken advantage of help proffered by Iran and Lebanese Hezbollah in the aftermath of the Arab Spring uprisings, which, as noted, was a moment of unsurpassed opportunity for the Houthis. Lebanese Hezbollah appears to have mentored the group, with Mareike Transfeld noting that “parallels in the Hezbollah takeover of West Beirut in 2008 and the Houthi grab of power in 2014 also suggest some exchange on military strategy.”40 Iran’s interest in Yemen seems to have been piqued when Riyadh entered the sixth war in late 2009, at which time an Iranian intelligence-gathering ship took up station in the Red Sea near Eritrea’s Dahlak Islands, on the same latitude as the Saudi-Yemeni border and the Yemeni port of Midi.g Two arms shipments were intercepted on their way to the Houthis in October 2009 between Eritrea and Houthi agents in Midi and Hodeida ports,41 with the Yemeni government claiming that five “Iranian trainers” were aboard one ship.42 The Houthis gained full control of Midi port in November 2011.h

There is no telling how many shipments of arms and personnel entered Yemen via this Houthi-friendly port, but the January 2013 interception of the Jihan-1 dhow suggests a powerful post-2011 effort by Iran to arm Ansar Allah in the same manner Iran has armed Lebanese Hezbollah. Intercepted by the U.S.S. Farragut off Yemen’s coast, the Jihan-1 carried the same kinds of Iranian-provided arms that Israel had previously intercepted off the coasts of Lebanon.43 These included 122-millimeter Katyusha rockets; Iranian-made Misagh-2 man-portable air defense system (MANPADS) rounds and battery units;i 2.6 tons of RDX high explosive; and components identical to Iranian-provided Explosively-Formed Penetrator (EFP)j mines used in Iraq and Lebanon.44 The vessel also carried Yemenis covertly moved in and out of Iran (i.e., not having gone through any immigration procedures).45 The United Nations Panel of Experts on Iran, which investigated the incident, found that “all available information placed the Islamic Republic of Iran at the center of the Jihan operation.”46

Days before Ansar Allah overran the Yemeni government’s fallback capital of Aden in March 2015, Tehran announced the commencement of an air bridge47 between Iran and Sana’a with a twice-daily shuttle service operated by Mahan Air, a government-controlled airline used by the IRGC Quds Force to ferry trainers and equipment to warzones.48 Leaders who were present in Sana’a in late 2014 suggest that Lebanese Hezbollah and Iranian trainers entered on these flights and up to 300 Yemenis were sent to Iran for training.49 k At the same time, in March 2015, both Al Jazeera and Al Arabiya news networks reported that an Iranian cargo ship had unloaded 180 tons of military equipment in the Red Sea port of Al-Saleef under conditions of tight security.50 According to Lebanese government officials, Iran supplied a small number of pilots to the Houthi movement in 2014 for unknown reasons.51 The capture of Yemen’s largest ports, airport, and its military establishment was complete, and Ansar Allah was readying to attempt a killing blow against the Yemeni government.

The Ansar Allah War Machine: 2015-2018

When the Houthis took Aden in March 2015, the 180-mile lunge was the longest-ranged offensive action ever undertaken by the group, and it coincided with a number of other offensives toward Mar’ib, Hodeida, Ta’izz, Ibb, Bayda, and Shabwah. Though most of these offensives failed to fully dislodge the defenders, the effort was an indication that the Houthi military was a much larger and more capable organization than it had been in 2010. The involvement of military units loyal to ousted president Ali Abdullah Saleh was one factor, particularly in enabling long-range helicopter-carried and ground forces to seize Aden,52 but from the outset, Ansar Allah did not trust Saleh networks and forced the demobilization of the Republican Guard, missile forces, and special forces units that would not operate under Houthi leadership.53 Indispensable individuals, such as the Missile Batteries Group commander Staff Brigadier General Mohammed Nasser al-Atufi, were coopted, and specialist personnel were retained.54 Overall, though, Ansar Allah’s priority was to bring all critical capabilities ‘in-house’ and to disarm all potential opposition, even if this meant greater near-term reliance on Iranian and Lebanese Hezbollah advisors.l

Since becoming a state-level actor with powerful international allies, the Houthi movement has been effective in recruiting, motivating, and training forces to fight the Yemeni government and the Gulf coalition. The remaining resources of northern Yemen55—taxes, printing of currency,56 and manipulation of fuel marketsm—are poured into sustaining Ansar Allah’s manpower, including an estimated $30 million per month of donated Iranian fuel.n Charismatic leadership remains at the core of the movement, with group solidarity reinforced by chanting and sermons at a proliferating series of festivals, workplace gatherings, summer camps, and classroom indoctrination sessions.o Ansar Allah exploits the deaths of Houthi leaders, the foreign-backed nature of the Yemeni government, and the use of southern troops in northern Yemen to tap into cultural drivers to broaden and boost recruitment.57 The Houthi movement classifies new recruits with limited indoctrination and training as mutahawith, which roughly translates to “Houth-ized” fighters.58 A significant proportion of these fighters are under 18 years of age, classifying them as child soldiers.59 According to Amnesty International, Ansar Allah imposes recruiting quotas in the areas it controls and will discipline clans who default.60 A mixture of indoctrination, machismo, material sustenance,p and threats have kept the Houthi movement well-supplied with new fighters across nearly a dozen major battlefields in Yemen for over three years of war.

Another factor that supports the sustainment of so many battlefields simultaneously is the very low force-to-space ratio that Ansar Allah employs, in part to mitigate the effects of total enemy air superiority. Fortification and defensive minefields are the cornerstone of this effort.61 Use of cave systems, trenches, and nocturnal raiding were its traditional means of blunting air attacks, but new methods have needed to be adopted since 2009, when the Royal Saudi Air Force and other modern air forces entered the fray. Trench systems continue to evolve, now including zig-zagging lines (to limit lateral spread of explosions); mortar pits with removable camouflage lids; arms caches and communications hubs at key junctions; and solar-powered communication systems. Fighting outside their native mountains, Ansar Allah uses “green zones” (vegetated wadis) to build bunkers under trees. Buildings are used as command hubs and arms caches, especially bridges, hospitals, and schools, which are known by the Houthis to be on restricted target lists or “no target” lists. Decoys and smoke canisters are used to complicate air surveillance and targeting.

The Houthis are effective at reducing signatures that could betray their location. Emissions control has become good since 2009, with limited use of electronic communications other than low-power Motorola phones.62 q Houthi fighters are renowned for being able to stay immobile under cover for long periods at hide sites, showing great discipline.63 In order to minimize their movements, Ansar Allah oversupplies posts with ammunition and water, and uses special rocket-assisted canisters to deliver food to outposts, delivering raisins, dates, corn, and fortified baby milk formula, and, of course, daily provision of qat, the chewable narcotic leaf.64

Another means of avoiding air attack is dispersion and tactical movement that is indiscernible from civilian movement. As one Gulf coalition officer noted, “they are very good at adapting to air threat with tactical movement, dispersing and moving with civilians.”65 Whereas Houthi forces operated in platoon- and company-sized warbands in 2004-2009, they have since atomized into tactical groups no bigger than three to five fighters.r Far back from the frontline, troops will be loosely managed by a very rudimentary Ansar Allah operations room under a district local area leader who is personally loyal to the Houthi family—a “Houthi Houthi” in Yemeni parlance.s This nominal headquarters will split reinforcements into tiny, largely autonomous cells, which are never bigger than the passenger capacity of a normal civilian car or frequently a two-man trail bike. The moving troops will often not have weapons, which complicates the positive identification requirements of air targeting, and will instead link up with cached weapons at the frontline. Their aim, which they have reached with a high amount of success, is to be indistinguishable from civilians.

To aid the economy-of-force effort, all defensive positions are covered by chaotically laid harassment minefields and trip wires, and any lost ground will be hastily booby-trapped before evacuation, even civilian homes, farms, and schools.t In defense of a trench complex, a single fighter will be expected to move from position to position, firing a machine-gun in one, a sniper rifle in another, and a B-10 recoilless rifle, medium mortar, or even an anti-tank guided missile (ATGM) in a third. Each fighter might have a one- to three-kilometer front to defend, and will be expected to defend the area successfully or die trying. Houthi fighters use Captagon-type amphetamine-based stimulants to reinforce morale in battle and use female contraceptive pills to aid blood-clotting if wounded.u As one Yemeni officer noted, “they take one tablet to stop them [from] bleeding and one to make them crazy.”66

In a 15-kilometer sector, there will thus be a thin outpost screen of highly determined and quite skilled marksmen. (The set-up does not appear to be greatly different in urban defense schemes, with the Houthis preferring to defend locales with long lines of fire rather than manpower-intensive street-by-street defenses.v) Behind this screen will be a pool of substitutes able to move forward quickly, not carrying weapons, to replace frontline fighters. Sometimes a veteran tactical reserve akin to a quick reaction force is kept back with the local area leader. The swarming of operational-level reserves to threatened points (such as Hodeida in May 2018) are triggered by national-level Houthi leaders, whereupon, as one Yemeni officer noted, “the trickle becomes a flood.”67

Houthi forces are notably less capable of advancing against enemy defensive positions that are covered by airpower. Though Ansar Allah excelled at the aforementioned slow wrestle to dominate geographic “hegemony points,”68 the movement has a poor record of dislodging alerted enemy defenses. In Aden at the start of the war, weak resistance forces backed by less than 10 UAE Special Forces blunted numerous Houthi battalion-sized assaults aided by pro-Houthi Republic Guard elements with tanks. Likewise, as recently as March 2018, a large Ansar Allah offensive involving around 1,000 attackersw tried unsuccessfully to break through Yemeni lines on the Nihm front, east of Sana’a, suffering heavy casualties. This last case is a rare example of Ansar Allah using one of its named elite unitsx—in that example, the Katibat al-Mawt (Death Brigade)69—to attempt an operational maneuver.

Where Ansar Allah has been notably more successful has been in the raiding war along with Saudi Arabia border, where it has fought a Hezbollah-style harassment campaign70 against Saudi border forces. Houthi forces have achieved great tactical success against Saudi border posts through offensive mine-laying on supply routes and ATGM strikes on armored vehicles and outposts.71 The Houthi military has sustained more than three years of continuous raids and ambushes, demonstrating its resilience and depth of reserves. Ansar Allah is now one of the premier practitioners of offensive mine warfare in the world, utilizing a range of explosive devices,y concealment tactics,72 z and initiation methods.73 aa The Houthis make very effective propaganda use of video from such raids, with a dedicated cameraman attached to all raiding parties, irrespective of size.ab By March 2018, the Houthi movement had also fought a long-running deadly ‘cat-and-mouse’ game of rocket launches under Gulf coalition aerial surveillance, launching 66,195 short-range rockets into Saudi Arabia, killing 102 civilians, wounding 843, and depopulating several hundred small villages.74

Advanced Houthi Weaponry and Capabilities

Alongside tactical evolution influenced by Lebanese Hezbollah, the Ansar Allah movement has debuted a range of advanced weapons systems since 2015 with direct assistance from Iran. The clearest example of this is the Burkan 2-H medium-range ballistic missile, which the Houthis have used since May 2017 to strike Riyadh and Yanbu, around 600 miles distant from launch points in northern Yemen. In January 2018, the U.N. Panel of Experts on Yemen found conclusively that Iran produced the Burkan-2 missiles fired from Yemen, which were “a derived lighter version” of Iran’s Qiam-1 missileac designed specifically to achieve the range capable of striking Riyadh. Wreckage from 10 Burkan missiles suggests that they were smuggled into Yemen in pieces and welded back together by a single engineering team, whose fingerprint non-factory welding technique was found on all the missiles.75 Iranian components were also integrated into repurposed Yemeni SA-2 surface-to-air missiles to produce the Qaher series of surface-to-surface free-flight rockets, which were used to strike targets up to 155 miles inside Saudi Arabia on over 60 occasions between 2015 and 2017.76 Though Ansar Allah gained control over some capable Yemeni engineers from 2014 onward, the Houthis’ smooth absorption of new missile systems suggest that Iranian training and technical assistance supported the missile campaign. First, there was no apparent learning curve that would suggest experimental deployment of entirely new rockets and missiles.ad Second, Ansar Allah did not rely upon the Saleh-era Missile Batteries Group for missile operations and quickly developed an independent capacityae to launch missiles, with one Yemeni military informant present in Houthi-controlled Yemen in 2014-2017 noting, “[the Houthis] didn’t trust us. The missiles were moved from Sana’a to Sa’ada early on. [The Houthis] were quickly self-sufficient and didn’t need the Republican Guard or missile forces.”77

Other less advanced but nonetheless important new weapons systems have also been debuted in the Houthi arsenal since 2015.af One is Ansar Allah’s Qasef-1 unmanned aerial vehicle, which the United Nations stated was “virtually identical in design, dimensions and capability to that of the Ababil-T, manufactured by the Iran Aircraft Manufacturing Industries.”78 Based on the design of the UAVs and the tracing of component parts, the panel concluded that the material necessary to assemble the Qasef-1s “emanated from the Islamic Republic of Iran.”79 An average of six Qasef-1 UAVs with explosive warheads have been launched each month since April 2017 by Ansar Allah, initially aimed at Gulf coalition Patriot missile batteries (to disrupt defenses ahead of surface-to-surface missile strikes) but increasingly against command centers (with unitary warheads at ranges up to 60 miles using GPS guidance) and even frontline troops (with bomb-releasing reusable UAVs under radio control).80

As with strategic missile systems, the Houthis took control of Yemen’s coastal missile batteries and then integrated them into an Iranian-supported salvage and modernization program. Since 2015, Ansar Allah has attacked shipping with naval mines and anti-ship missiles that were already in the Yemeni arsenal,ag to which it has added the use of boat-mounted ATGMs.81 The Houthis developed around 30 coast-watcher stations,ah “spy dhows,” drones, and the maritime radar of docked ships to create targeting solutions for attacks.82 Ansar Allah has also undertaken combat diver training on Zuqur and Bawardi islands in the Red Sea.i The most significant technological development undertaken by the Houthis in coastal defense was the conversion (with Iranian supportaj) of coast guard speedboats into the self-guiding Shark-33 explosive drone boat, which can be programmed to follow a course or home in on a target using electro-optical television guidance.ak This kind of device was used to successfully attack a Saudi frigate on January 30, 2017, (using television guidance) and unsuccessfully to attack a Saudi oil loading terminal on April 26, 2017 (using GPS guidance while maneuvering at 35-45 knots).83 The Shark 33 has been employed by the Houthis in a triangular formation, with the attack boat forward, a command boat nearby, and a media boat (to capture combat footage) further away.84 On one occasion, a Shark 33 was camouflaged by being loaded with fish.85

The accumulated balance of evidence strongly suggests that Iran and Lebanese Hezbollah have developed powerful military and technical advisory missions in Yemen since 2014. According to Yemeni leaders present in Sana’a between 2014 and 2017, IRGC advisors were confined to Sana’a and to a missile construction site in Sa’ada. These advisors were “like a diamond to the Houthis” and were “kept in safe places to help give operational and strategic advice and guidance on tactics and procedures.”86 Lebanese Hezbollah operatives were more numerous and were not only kept in Sana’a and Sa’ada but also allowed forward as far as command posts and the Red Sea coastal defense sites.87 Hezbollah provided mentoring and training in infantry tactics, ATGM operations, offensive mine warfare, and anti-shipping attacks.88 A number of small-scale military industries have been established since 2014 to support the Houthi war effort and maximize domestic reuse and production capabilities, in order to minimize the effect of the international arms embargo on the Houthi movement. A land-mine production facility was established in Sa’ada, feeding around 20 tons of mines per day to distribution hubs in Sana’a, Hodeida, and Dhamar.89 A separate EFP fabrication facility was established in Sana’a.90 As mentioned earlier, a missile construction hub was transferred from Sana’a to Sa’ada. In Hodeida, a drone workshop operates, drawing on a supply of rolls of fiber-glass to make airframes.91

Outlook and Implications

The above analysis demonstrates that the rise of Houthi military power is neither solely the result of its own successful effort to capture the state, nor solely Iranian support, but rather a combination of the two. The Houthi family has proven to be politically prodigious and very adept at seizing opportunities. In their view, they have restored the ousted thousand-year Zaydi imamate, achieving the aim of Zaydi revivalism championed by the family’s patriarch, the late Badr al-Din al-Huthi. They will not willingly give up their control of Sana’a or a Red Sea coastline.92 Though Ansar Allah has been fought out of many parts of southern and eastern Yemen, these were the outer bulwarks of its defense, while the more defensible northern highlands remain almost entirely under its control. It does not feel defeated.93 Even if Hodeida and the Red Sea coast should fall to the Yemeni government and the Gulf coalition, the Houthi movement will probably fight on and will be very hard to defeat in a second phase of the war in northern Yemen.

The Houthi movement has proven itself to be a very tough military opponent. Fourteen years of conflict has strengthened it, and it thrives under the conditions of war. At a tactical level, as one Gulf coalition officer noted, echoing a common sentiment, “they are tough, willing to die, they’re organized and they’re getting better with time.”94 In 2010, a RAND study posed the question of whether the Houthis could move beyond a fighting style of “unconnected fighting groups” to form “a coordinated, synchronized fighting force,” and this is exactly what they have done, weaving micro-warbands into a cohesive war effort capable of defending in depth.95 At the strategic level, the Houthis (likely with mentoring from Iran) have learned how to pull geopolitical levers through medium-range ballistic missile strikes on Riyadh, threats to close the Bab al-Mandeb Strait, and deft use of propaganda to vilify the Gulf coalition and the Yemeni government.

Iran does not appear to control the Houthi leadership, but it did ramp up its support to the Houthis at precisely the moment that their ambitions broadened not only to control northern Yemen but also to build defensive bulwarks far outside the traditional Zaydi heartland. The Houthis could arguably have taken northern Yemen without Iran’s help, and there are indications Tehran warned against this step. But Iran has provided critical aid in allowing the Houthis to slow down the Gulf-backed Yemeni government recapture of terrain. The relationship between Iran and the Houthis could remain transactional or it could deepen. Iran, Lebanese Hezbollah, and Ansar Allah share a strikingly similar worldview opposing the United States, Israel, and Saudi Arabia, as underlined by the Houthi slogan: “Death to America, Death to Israel, Curse upon the Jews, Victory to Islam.”96 Hardliner military commanders within the Houthi movement such as Abdullah Eida al-Razzami and Abdullah al-Hakim (Abu Ali)97 may be more susceptible to IRGC influence than other parts of the Houthi hierarchy, and this wing of the movement could be strengthened over time, particularly if the current war continues. As one expert on Yemen told the author, “some Houthi leaders think the Saudis want to exterminate them down to the last man, woman and child, and they want to continue the war to Makkah”98 (in Saudi Arabia). Though it clearly lacks the capacity to take such 0ffensive action, Ansar Allah is more than capable of becoming a “southern Hezbollah” on the Red Sea, flanking Saudi Arabia and Israel from the south, a factor that continues to drive the Gulf coalition’s efforts to deprive the Houthis of a coast through which to draw on Iranian and Hezbollah assistance in the future.

Substantive Notes

[a] Referring to the dynasty that ruled Persia in 1502–1736 and installed Shi`a Islam over Sunnism.

[b] The RAND study notes that “around 15,000 boys and young men had passed through Believing Youth camps each year,” adding that the Believing Youth was an ideal mechanism to groom a fighting cadre, noting “that demographic base—or their younger siblings—went on to provide a recruitable hard core, susceptible (or vulnerable) to the masculine assertion furnished by resistance and armed activity … the rituals or gatherings appropriated by the Huthis—where adolescents and young adults congregate together with ‘adult’ fighters—make ideal environments for socialization and recruitment of youth.” Barak Salmoni, Bryce Loidolt, and Madeleine Wells, Regime and Periphery in Northern Yemen: The Huthi Phenomenon (Santa Monica: RAND, 2010), p. 254.

[c] Marieke Brandt suggests that historical rivalry between Abdulmalik al-Houthi and Abdullah Eida al-Razzami was put on hold during 2011 to allow the movement to maximize its gains. See Marieke Brandt, Tribes and Politics in Yemen: A History of the Houthi Conflict (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), p. 186.

[d] Houthi military units had used the name Ansar Allah as early as 2007 in Al-Jawf governorate. See Brandt, Tribes and Politics in Yemen, p. 188.

[e] These included the Missile Batteries Group and Missile Research and Development Center. See Tom Cooper, “How Did the Houthis Manage to Lob a Ballistic Missile at Mecca?” War is Boring, January 2, 2017.

[f] The Political Security Organization (PSO) and National Security Bureau (NSB). In 2013, the PSO released all of the Lebanese foreign nationals it was holding for suspicion of ties to Lebanese Hezbollah. Author interview, Yemen expert A, spring 2018. Name of interviewee, and date and place of interview withheld at interviewee’s request.

[g] The current Iranian ‘mother ship’ on station is Saviz, located in Eritrea’s contiguous waters. It has a crew complement of 20 but usually has around 60 personnel on board, many of whom wear Iranian naval uniforms, despite the fact that the ship is registered as a civilian vessel. The ship has signals intelligence domes and antennae. It is visited by all Iranian ships moving through the Red Sea, nominally to coordinate anti-piracy measures. At least three speedboats are based on deck, which are used to ferry personnel to Yemen. The author interviewed a number of Gulf coalition naval personnel with regard to Saviz and reviewed imagery of the vessel. Author interview, Gulf coalition naval personnel. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[h] Previously, Arabic news reporting suggested Iran had tried to invest in Midi port in 2009. See “Tehran Aims to Turn Yemen into a Regional Arena for Conflict, as Part of Its Ongoing Dispute with Several Countries in the Region,” Al-Watan, October 31, 2009.

[i] The Misagh is an Iranian copy of the Chinese QW-1M, which is itself a copy of the U.S. Stinger. What is notable is that the Jihan-1 did not carry MANPADS gripstocks (the trigger mechanism), indicating that these may already have been present in Yemen. “Frontline Perspective: Radio-Controlled, Passive Infrared-Initiated IEDs: Iran’s latest technological contributions to the war in Yemen,” Conflict Armament Research, March 2018, p. 10.

[j] The Jihan-1 carried a consignment of passive infrared sensors and nearly 2,000 electronic components used in the manufacture of RCIEDs. See “Frontline Perspective: Radio-Controlled, Passive Infrared-Initiated IEDs: Iran’s latest technological contributions to the war in Yemen,” Conflict Armament Research, March 2018, p. 10.

[k] Senior Yemeni leaders present in Sana’a were able to discern the presence of Hezbollah and Iranian trainers, despite efforts taken to hide these personnel.

[l] This was a common feature across the author’s interviews of Yemeni military officials who were present in Houthi-held areas in 2014-2017.

[m] The Houthi clan shared fuel imports into northern Yemen via Hodeida and Saleef ports until the death of Ali Abdullah Saleh, at which point the last 14 fuel-importing companies not under their control were absorbed into their network. Author interview, Yemen (economic) experts B and C, spring 2018. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[n] The United Nations is reported to be investigating provision of around $30 million per month of fuel to Ansar Allah by Iranian shell companies. See Carole Landry, “UN panel finds further evidence of Iran link to Yemen missiles,” Agence France-Presse, July 31, 2018. The author found that numerous interviewees from the Gulf coalition naval forces and even from the humanitarian community were convinced that the Houthis were receiving “gratis” fuel transfers from Iran as a form of untraceable threat finance.

[o] The RAND 2010 study noted the Houthi development “groupness” relied heavily upon chanting of the Houthi slogan at celebrations including al-Ghadir Day, the Prophet’s Birthday, International Jerusalem Day, and the Commemoration of Martyrs Day. See Salmoni, Loidolt, and Wells, pp. 219 and 236.

[p] Being a fighter displaces the burden of feeding a youth from the family onto Ansar Allah. Families also receive around $80-120 per month if a child becomes a martyr at the frontline. See “Yemen: Huthi forces recruiting child soldiers for front-line combat,” Amnesty International, February 28, 2017.

[q] Though it is beyond the scope of this study, Houthi leadership use of Telegram and other messaging applications has become more sophisticated since 2015, though rural frontline tactical communications remain largely unchanged. Drawn from the author’s interviews with coalition intelligence personnel.

[r] This trend was apparent by December 2009.

[s] This phrase seemed to be widely in use among Yemeni and Gulf coalition forces to describe Houthi fighters who were actually from the Houthi home province of Sa’ada.

[t] The author spoke to multiple Gulf coalition explosive ordnance technicians and Yemeni civilians with direct exposure to Houthi booby-trapping of civilian homes, farmlands, and schools. The very vindictive and inventive concealment of explosive booby traps inside children’s toys and furniture is difficult to reconcile with the Houthis’ apparent desire to be viewed as victims in the war.

[u] References to Houthi uses of an amphetamine-based combat drug and a blood-clotting drug were widely made during the author’s interviews with Yemeni and Gulf coalition forces.

[v] For instance, individual Houthi fighters will often snipe from a mined-in water tower, rooftop, or pylon until killed. In the author’s interviews with Gulf coalition troops, such fighters were often compared to Second World War-era Japanese diehards or Vietnam-era Vietcong.

[w] The author was able to visit this sector around a week after the offensive and interview commanders in spring 2018. Yemeni commanders describe burying around 300 Houthi fatalities and capturing 60 wounded fighters. The Houthi troops, largely described as teenagers, were repelled with very heavy use of airpower.

[x] As well as Katibat al-Mawt, there has historically been reference to Kataib Badr (in the fourth war in 2007) and the Kataib al-Hussein (a three-battalion praetorian force); and a discipline battalion. The author worked in Yemen previously (during the fourth and fifth Houthi wars) and gathered some of this data during interviews then, backed up by further interviews of Yemeni commanders on the Nahim front in 2018.

[y] These include Explosively-Formed Penetrator, large 120mm-diameter shaped charges, directional charges and claymore warheads, repurposed naval mines, plus anti-tank and anti-personnel mines. Author interview, Gulf coalition explosives ordnance technicians. Names of interviewee, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[z] These include off-road concealment within synthetic rocks, concealment within fabricated kerbstones, elevated in trees, surface-laid under patched tarmac, and surface-laid in culverts.

[aa] These include passive infrared, radio-control, pressure plate, and crush wire.

[ab] One Saudi officer noted, “they always have a combat cameraman, even if he is one out of three men in the group.” Author interview, Gulf coalition senior officer A, spring 2018. Name of interviewee, and date and place of interview withheld at interviewee’s request.

[ac] The United Nations concluded that the “internal design features, external characteristics and dimensions [of the remnants] are consistent with those of the Iranian designed and manufactured Qiam-1 missile.” “Letter dated 26 January 2018 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen mandated by Security Council resolution 2342 (2017) addressed to the President of the Security Council,” p. 28.

[ad] Iran has been converting SA-2 missiles into Tondar-69 ballistic missiles since the 1990s, which likely informed the rapid fielding of Qaher-1. The United Nations confirmed that Iran produced the components used in the Burkan-2H, and these components are not owned by any country other than Iran. The creation of an entirely new extended range version of the Qiam-1, and its smooth operational adoption in Yemen, suggests four to six months of development work in Iran, followed by the training of Yemeni or Iranian assemblers and operators for what was a new weapons system. Author interviews, three weapons inspectors with direct access to multiple Burkan 2H missiles. Names of interviewee, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[ae] Houthi-shot video viewed by the author does show some missile systems such as the OTR-21/SS-21 Scarab system being fired using rudimentary procedures by non-uniformed Houthi fighters—uncovering the device from within a false water tanker, raising it on a hydraulic arm, and firing it using electric charge from car batteries.

[af] Other innovations include Russian-made, heat-seeking air-to-air missiles into truck-launched antiaircraft weapons and Iranian virtual radar receivers that passively gather air traffic control signals to derive targeting solutions for air-defense batteries. See Farzin Nadimi and Michael Knights, “Iran’s Support to Houthi Air Defenses in Yemen,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, April 4, 2018.

[ag] Likely older P-21 “Styx II” (and its HY-2 Chinese version) and C-801 missiles, but potentially also C-802 systems provided by Iran or Lebanese Hezbollah. See Alexandre Mello, Jeremy Vaughan, and Michael Knights, “Houthi Antishipping Attacks in the Bab al-Mandab Strait,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, October 6, 2016.

[ah] Ansar Allah training videos viewed by the author showed vessel identification classes focusing on Saudi Arabian Al-Madinah class frigates and UAE Baynunah-class corvettes.

[ai] Ansar Allah training videos viewed by the author show a section of 10 trainees wearing Beuachat diving suits and receiving training on mission planning.

[aj] Forensic evidence from a captured Shark 33 and arms interdictions show that Shahid Julaie Marine Industries, Iran’s main builder of drone boats, provided key components in the Shark 33, while the computer hard drive inside the Shark-33 held over 90 sets of coordinates for locations in Iran, Yemen, and the Red Sea, including the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Self-Sufficiency Jihad Organization labs in Tehran, which were also captured in a test shot of the onboard camera. See Michael Knights, “Making the Case against Iranian Sanctions Busting in Yemen,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, December 15, 2017.

[ak] The author was provided with access to the Shark 33 onboard computer and electro-optical systems, and saw a demonstration of the electro-optical tracking and had a chance to interview a U.S. weapons intelligence analyst in fall 2017 about the system. Name of interviewee, and date and place of interview withheld at interviewee’s request.

Citations

[1] Barak Salmoni, Bryce Loidolt, and Madeleine Wells, Regime and Periphery in Northern Yemen: The Huthi Phenomenon (Santa Monica: RAND, 2010), p. 189. Salmoni, Loidolt, and Wells noted that the Houthis are known by a variety of names: “the “Huthis” (al-Huthiyin), the “Huthi movement” (al-Haraka al-Huthiya), “Huthist elements” (al-‘anasir al-Huthiya), “Huthi supporters” (Ansar al-Huthi), or “Believing Youth Elements” (‘Anasir al-Shabab al-Mu’min).”

[2] Marieke Brandt, Tribes and Politics in Yemen: A History of the Houthi Conflict (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 7, 21, 114.

[3] Salmoni, Loidolt, and Wells, p. v. See also Eleonora Ardemagni, “From Insurgents to Hybrid Sector Actors? Deconstructing Yemen’s Huthi Movement,” Istituto per gli Studi di Politica Internazionale, April 2017.

[4] Salmoni, Loidolt, and Wells, p. v.

[5] See the dedicated chapter on this theme in Brandt, Tribes and Politics in Yemen, pp. 75-97.

[6] Salmoni, Loidolt, and Wells, p. v.

[7] Ibid., pp. v and 99. Also see Brandt, Tribes and Politics in Yemen, pp. 116-118.

[8] Brandt, Tribes and Politics in Yemen, pp. 75-97.

[9] Ibid., pp. 132-133.

[10] Ibid., pp. 75-97.

[11] Ibid., p. 199.

[12] Ibid., pp. 166-170.

[13] Ibid., pp. 230-231.

[14] Salmoni, Loidolt, and Wells, p. 8.

[15] Brandt, Tribes and Politics in Yemen, p. 295. Also see Marieke Brandt, “The Irregulars of the Sa‘dah War: ‘Colonel Shaykhs’ and ‘Tribal Militias’ in Yemen’s Huthi Conflict (2004-2010),” in Helen Lackner ed., Why Yemen Matters: A Society in Transition (London: Saqi Books, 2014), p. 114.

[16] Brandt, Tribes and Politics in Yemen, pp. 171, 177, and 199.

[17] Salmoni, Loidolt, and Wells, p. 254.

[18] This Paul Dresch translation of asabiyyah is quoted from Brandt, “The Irregulars of the Sa‘dah War,” p. 114.

[19] Salmoni, Loidolt, and Wells, p. 254.

[20] Ibid., p. 252.

[21] See the chapter on the six Houthi wars in Salmoni, Loidolt, and Wells, pp. 200-204, 231.

[22] Ibid., p. 209.

[23] Ibid., p. 134.

[24] Brandt, Tribes and Politics in Yemen, p. 323.

[25] Nasser Arrabyee, “Al Houthi desperation mounts as tribesmen join forces with troops,” Gulf News, December 8, 2009.

[26] For a description of the “hostages for obedience” system, see Brandt, Tribes and Politics in Yemen, pp. 40-42. For further historical context, see Edgar O’Ballance, The War in Yemen (Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1971), pp. 28-29.

[27] Simon Henderson, “Small War or Big Problem? Fighting on the Yemeni-Saudi Border,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, November 10, 2009.

[28] Salmoni, Loidolt, and Wells, pp. 200-204.

[29] Brandt, Tribes and Politics in Yemen, pp. 244 and 268.

[30] Salmoni, Loidolt, and Wells, pp. 219-220.

[31] Brandt, Tribes and Politics in Yemen, p. 212.

[32] Henderson.

[33] Quoted by Brandt, Tribes and Politics in Yemen, p. 187.

[34] Ibid., p. 333.

[35] Mareike Transfeld, “Iran’s Small Hand in Yemen,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, February 14, 2017.

[36] Marieke Brandt, “Sufyan’s ‘Hybrid’ War: Tribal Politics During the Huthi Conflict,” Journal of Arabian Studies: Arabia, the Gulf, and the Red Sea 3:1 (2013): p. 135.

[37] Author interview, Yemen expert A, spring 2018. Name of interviewee, and date and place of interview withheld at interviewee’s request.

[38] Author interview, Yemen expert A, spring 2018. Name of interviewee, and date and place of interview withheld at interviewee’s request.

[39] See Tom Cooper, “How Did the Houthis Manage to Lob a Ballistic Missile at Mecca?” War is Boring, January 2, 2017.

[40] Transfeld.

[41] Brandt, Tribes and Politics in Yemen, p. 315.

[42] See “Yemenis intercept ‘Iranian ship’,” BBC, October 27, 2009, and Oren Dorell, “Iranian support for Yemen’s Houthis goes back years,” USA Today, April 20, 2015.

[43] C. J. Chivers and Robert Worth, “Seizure of Antiaircraft Missiles in Yemen Raises Fears That Iran Is Arming Rebels There,” New York Times, February 8, 2013. See also Michael Knights, “Responding to Iran’s Arms Smuggling in Yemen,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, December 2, 2016.

[44] “Frontline Perspective: Radio-Controlled, Passive Infrared-Initiated IEDs: Iran’s latest technological contributions to the war in Yemen,” Conflict Armament Research, March 2018, p. 10.

[45] See pages 14 and 15 of “Final Report of the Panel of Experts Established Pursuant to Resolution 1929 (2010), S/2013/33,” United Nations Security Council, June 2013.

[46] Ibid.

[47] “Iranian Flight Lands In Yemen After Aviation Deal,” Radio Free Europe, March 1, 2015.

[48] “Treasury Targets Supporters of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and Networks Responsible for Cyber-Attacks Against the United States,” U.S. Treasury, September 14, 2017.

[49] Author interviews, Yemeni political and military leaders present in Sana’a in 2014-2017. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[50] Quoted in Dorell.

[51] Ibid. Dorell quotes David Schenker, director of Arab politics at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, who said that Lebanese officials hosted Iranian military pilots in Beirut “where they received Lebanese passports and then traveled to Yemen to join the fighting in advance of the Houthi takeover earlier this year.”

[52] Author interviews, Yemeni political and military leaders present in Sana’a in 2014-2017. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[53] Author interviews, Yemeni political and military leaders present in Sana’a in 2014-2017. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[54] Author interviews, Yemeni political and military leaders present in Sana’a in 2014-2017. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[55] “Letter dated 26 January 2018 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen mandated by Security Council resolution 2342 (2017) addressed to the President of the Security Council,” see Annex 45, pp. 186-188.

[56] See “Treasury Designates Large-Scale IRGC-QF Counterfeiting Ring,” U.S. Treasury, November 20, 2017.

[57] Author interview, Yemen expert A, spring 2018. Name of interviewee, and date and place of interview withheld at interviewee’s request.

[58] Author’s interviews, Yemen experts and coalition military officials. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[59] As defined by the U.N. Charter, Chapter IV (Human Rights), Part 11 (Convention on the Rights of the Child), November 20, 1989.

[60] See “Yemen: Huthi forces recruiting child soldiers for front-line combat,” Amnesty International, February 28, 2017.

[61] This paragraph draws on extensive interview material. Michael Knights, interviews and embedded observation with Gulf coalition targeting officers in spring 2018. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request. The author met and talked with a number of former Houthi-controlled child soldiers also in spring 2018.

[62] For a review of Houthi communications practices before 2010, see Salmoni, Loidolt, and Wells, p. 196.

[63] Author interviews and embedded observation, Gulf coalition targeting officers. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[64] Author interviews, Jizan front Gulf coalition commanders and officers. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[65] Author interviews, Gulf coalition intelligence personnel. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request. The author can attest to the care and ingenuity with which Houthi forces move in civilian guise, having watched many hours of live and recorded surveillance footage.

[66] Author interview, Yemeni military officer, spring 2018. Name of interviewee, and date and place of interview withheld at interviewee’s request.

[67] Author interview, Gulf coalition military officer, spring 2018. Name of interviewee, and date and place of interview withheld at interviewee’s request.

[68] Quoted in Brandt, Tribes and Politics in Yemen, p. 287.

[69] Author interviews, Nahm front, 2018. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[70] For a good overview of Lebanese border fighting between Hezbollah and Israel, see Nick Blanford, Warriors of God: The Inside Story of Hezbollah’s Relentless War Against Israel (New York: Random House, 2011).

[71] See Lori Plotkin Boghardt and Michael Knights, “Border Fight Could Shift Saudi Arabia’s Yemen War Calculus,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, December 6, 2016.

[72] Author interview, Gulf coalition explosives ordnance technicians, spring 2018. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[73] Author interview, Gulf coalition explosives ordnance technicians, spring 2018. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[74] Author interview, Gulf coalition humanitarian operations personnel, spring 2018. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[75] Author interviews, three weapons inspectors with direct access to multiple Burkan 2H missiles. Names of interviewee, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[76] See Michael Knights, “Making the Case against Iranian Sanctions Busting in Yemen,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, December 15, 2017, and Michael Knights and Katherine Bauer, “How Europe Can Punish Iran’s Missile Smuggling While Preserving the Nuclear Deal,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, February 27, 2018.

[77] Author interviews, Yemeni political and military leaders present in Sana’a in 2014-2017. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[78] “Letter dated 26 January 2018 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen mandated by Security Council resolution 2342 (2017) addressed to the President of the Security Council,” p. 32.

[79] Ibid.

[80] Author interviews, two weapons inspectors with direct access to multiple Houthi drones. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[81] See Michael Knights and Farzin Nadimi, “Curbing Houthi Attacks on Civilian Ships in the Bab al-Mandab,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, July 27, 2018.

[82] Author interview, NGO worker based in Yemen, spring 2018. Name of interviewee, and date and place of interview withheld at interviewee’s request.

[83] Author interview, Gulf coalition naval officers with direct involvement in repelling the oil loading terminal attack, spring 2018. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[84] Author interview, Gulf coalition naval officers with direct involvement in repelling the oil loading terminal attack, spring 2018. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[85] Author interview, Gulf coalition naval officers with direct involvement in repelling the oil loading terminal attack, spring 2018. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[86] Author interviews, Yemeni political and military leaders present in Sana’a in 2014-2017, spring 2018. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request. Some senior interviewees have met unnamed IRGC advisors in Sana’a in 2014-2017.

[87] Author interviews, Yemeni political and military leaders present in Sana’a in 2014-2017, spring 2018. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request. Some senior interviewees have met unnamed IRGC advisors in Sana’a in 2014-2017.

[88] Author interviews, Yemeni political and military leaders present in Sana’a in 2014-2017, spring 2018. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request. Some senior interviewees have met unnamed IRGC advisors in Sana’a in 2014-2017.

[89] Author interviews, Yemeni political and military leaders present in Sana’a in 2014-2017. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request. Some senior interviewees have met unnamed IRGC advisors in Sana’a in 2014-2017. These findings are broadly echoed by weapons intelligence experts (interviewed by the author) who have hands-on access to Houthi munitions, which shows signs of being mass-produced at one hub and being distributed sub-nationally afterward.

[90] Author interviews, Yemeni political and military leaders present in Sana’a in 2014-2017. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request. Some senior interviewees have met unnamed IRGC advisors in Sana’a in 2014-2017. These findings are broadly echoed by weapons intelligence experts interviewed by the author, who have hands-on access to Houthi munitions.

[91] Author interviews, Yemeni political and military leaders present in Sana’a in 2014-2017. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request. Some senior interviewees have met unnamed IRGC advisors in Sana’a in 2014-2017. These findings are broadly echoed by weapons intelligence experts interviewed by the author, who have hands-on access to Houthi munitions.

[92] Author interview, Yemen expert A, spring 2018. Name of interviewee, and date and place of interview withheld at interviewee’s request.

[93] Author interview, Yemen expert A, spring 2018. Name of interviewee, and date and place of interview withheld at interviewee’s request. This is the sense among most Yemen analysts consulted for this study.

[94] Author interview, Gulf coalition officer, spring 2018. Name of interviewee, and date and place of interview withheld at interviewee’s request.

[95] Salmoni, Loidolt, and Wells, p. 238.

[96] Ibid., pp. 132-133.

[97] Author interview, Yemen expert A, spring 2018. Name of interviewee, and date and place of interview withheld at interviewee’s request.

[98] Author interview, Yemen expert A, spring 2018. Name of interviewee, and date and place of interview withheld at interviewee’s request.