Germany’s ignored transnational organized crime risk?

Clan criminality is perceived as a worrying trend in Germany. Law enforcement needs to engage new strategies to successfully combat these structures, an ‘external’ criminal threat within the country and beyond.

Clan criminality in Germany has received increased media attention in the past years. Although criminal offences committed by clans were thought to constitute a very small proportion of all offences in the country in 2020, the visibility and impact of clan criminality – including the 2019 high-profile heist of historic jewels worth an estimated €113.8 million – has made this phenomenon a priority.

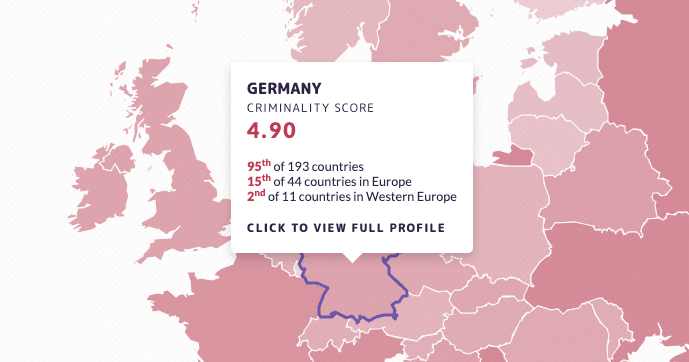

According to the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime’s Global Organized Crime Index 2021, Germany has a criminal actor score of 5.00 in the ‘mafia-style groups’ indicator, one of the highest for countries in Western Europe and above the global average of 3.89. Its criminal foreign actors score of 6.50 is also higher than the global average (5.27).

In Germany, mafia-style groups (i.e. organized criminals with a known name, a defined leadership, territorial control and identifiable membership) include both foreign and domestic groups, such as the Italian mafia, Russian-Eurasian organized crime groups, biker gangs and the so-called clan organizations.

Clan criminality is perpetrated by family-based networks, who commit a variety of crimes such as armed robberies, theft, bombing of ATM machines, money laundering and drug trafficking. ‘We are dealing here with … serious criminals … with robbery, fraud and organized crime … This shows that some of the clans are playing in the same league as the mafia,’ said Herbert Reul, Interior Minister of the North Rhine-Westphalia state.

Clan groups are known for their tight-knit structures based on familial ties, but most of all for their aggressive behaviour towards the police and other state agencies. State responses to the problem have focused on areas such as cooperation between state forces, confiscation of illegal wealth, investigation of minor offences and, perhaps most importantly, the development of strategies designed to deter young clan members from pursuing criminal careers.

In February 2021, some 500 police officers from Berlin and Brandenburg searched over 20 homes after information on illegal weapon deals had been uncovered. In another case, a clan member is accused of money laundering and organizing a cocaine courier service to Berlin.

German clan criminality is not a uniquely domestic phenomenon. Although most clan-related criminal activities are committed in Germany, according to the Federal Criminal Police Office’s 2020 criminality report, there were 29 organized crime proceedings in which members of German clans were active in other countries. Often, the informal hawala payment system is used to transfer money across borders.

Classification of criminal actors

There is no clear or agreed-upon definition for clan criminality. In Germany, perpetrator groups are understood as ethnic subcultures, usually comprising large families. These family-associated structures also include the Italian mafia, groups of Western Balkan or Russian-Eurasian origin, and clan families of Arab or Turkish origin. Although this is the terminology used in Germany, it is important to note that it refers mainly to the groups’ migration background, not their citizenship. Second- and third-generation members of these family clans have been born in Germany and have German citizenship.

German law enforcement agencies compiled a number of indicators and criteria to help define clan criminality in connection to organized crime, including kinship ties, a strong focus on a patriarchal-hierarchical family structure, ideological legitimation of criminal activity, rejection of the German legal system and use of violence.

These criteria show a clear difference in modus operandi when compared with other organized crime groups without deep family linkages. However, clan criminality is far more visible due to its open aggression towards and disregard of state authority compared to the more subtle agency of the Italian mafia, for example. Its kinship structures are also more closed, keeping membership restricted to blood relations. This complicates the use of certain counter-crime strategies used against other mafia-style groups. For instance, undercover operations are impossible unless a family member of the group is deployed for this purpose.

The specific characteristics of clan criminality become clear when tracing its origin and growth over the years. During migration flows of the 1970s to the 1990s, many Arabic-speaking Kurdish groups fleeing the Lebanese civil war found refuge in Germany. Already secluded minorities in Lebanon, these refugees stayed in large, tight-knit family structures, isolated from the larger German society. Other (non-Kurdish) groups, including families from Palestine, such as the Abou-Chaker-Clan active in Berlin, share a similar history and often similar internal structures.

Responses

Arguably, this formation of an ethnic ‘parallel society’ presents one of the major challenges to police and law enforcement. As some clan families in Germany have up to 2 500 members, it is important to recognize that not all family clans, nor all members of specific clans, are involved in criminality. However, clan members do tend to look after one another’s interests, and the efficacy of tried investigation methods such as witness testimony, undercover agents and telephone surveillance, among others, is limited, as members will not turn against each other.

State responses have been criticized for not having done enough to address the threat. This may be due to the ethnicity factor, which makes targeting clan criminality a politically delicate issue. Groups’ integration into Germany society presents a major challenge and attempts to incorporate arbiters to mediate inter-clan disagreements – which often lead to violence – have been criticized as enabling a form of ‘parallel justice’, hindering true integration.

A systematic approach is needed, starting at the roots of the issue. Experts have emphasized that the state must demonstrate its presence and authority early, not only to signal to society that all areas of a city are safe (and also counter media hysteria), but also to respond to the lack of respect of state law enforcement exhibited by clan members. Any forms of ‘parallel justice’, as promising as they may seem in the short term, ought to be limited. If the clan crime phenomenon is rooted in the failure of certain groups to integrate into German society (or the state’s failure to help integrate them), then solutions must incorporate strategies that address this failing. A clear stance on what clan criminality actually entails, and an operational definition, would also offer a stronger basis for actionable interventions.